THE CHEERFUL CITY

In Kashgar, a report from the outpost caused a stir. By order of the authorities, the city was declared to be in a state of martial law: an increased guard was placed on the fortress walls, and mounted patrols roamed the streets at night.

Wishing to prevent bloodshed and save the city from further looting, the rulers decided to send experienced officials to scout the caravan camped twelve kilometers from the city gates, near the tomb of Kufalla-Khodja. The officials, mourned by their wives like condemned men, were not in a hurry to meet their certain doom.

Meanwhile, the caravan was not wasting time: without waiting for a meeting with the authorities, Musabay, along with several old caravan drivers who had been to Kashgar before, rode into the city to "give greetings" to the elder. The elder Nasir ad-Din remained completely calm—he did not immediately believe the absurd rumors and warmly welcomed his old acquaintance Musabay, with whom he had feasted many times at joyful Kashgar celebrations—mashrebs; he immediately sent a zaketchi—a collector of religious taxes for the benefit of Muhammad—and even his own son to the caravan.

Following the zaketchi, a Kashgar official, one of the bravest, arrived; after talking with Musabay and quickly inspecting the camp, he, unable to contain his joy, rode off to reassure the city.

The next day, after finishing the zaket and sending the livestock to graze, the caravan headed towards Kashgar. But they had not traveled half the distance when they were stopped by important officials dressed in Chinese attire, who this time maintained a demeanor of utmost dignity. One of them, the most powerful, Ismail-Bek, ordered the packs to be untied for inspection. Evening was approaching, and the beks postponed the inspection until morning. Over dinner, not sparing gifts, Musabay persuaded Ismail-Bek to allow the caravan into the city... On the dusty road between fields sown with jugara and musuy fodder, the caravan approached Kashgar; they crossed a wooden bridge over the Tyumen River. Valikhanov rode ahead, next to Musabay, who again, as at the San-Tash pass, indulged in praising Kashgar.

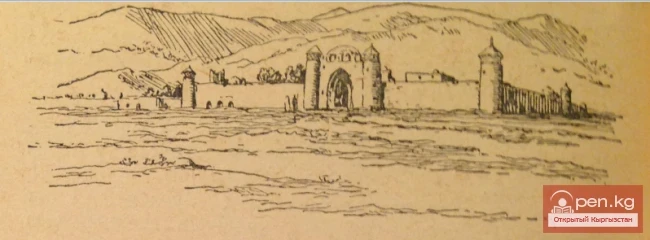

We will feast, we will drink wine, there will be women,—clinking with delight, said Musabay. Valikhanov, remembering the strict Muslim customs, listened to Musabay with surprise, but at that moment he could not doubt the tales—the high city wall with light lattice towers at the corners was already visible ahead. Soon Valikhanov would have the opportunity to verify everything for himself. He even rose in his stirrups, as if eager to peek at the city's secrets, but the high wall concealed both houses and gardens, and from a distance, it seemed that there was nothing behind it.

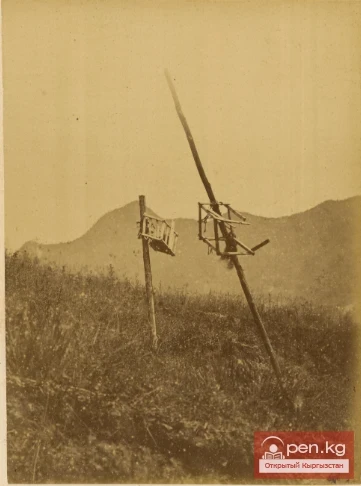

There were only a few hundred meters left to the open gates when Valikhanov's attention was drawn to a strange alley of poles set up on both sides of the road. A crossbar was nailed to each pole, and a cage was hung from the bar...

— What is this? — Valikhanov involuntarily exclaimed.

— The heads of executed rebels, supporters of the khodja,— replied Musabay, turning his head as if the collar of the spacious Bukhara robe gifted by the elder had suddenly tightened around his neck. Valikhanov instinctively repeated his movement and grasped his throat, feeling the delicate pulsating vein beating under his thumb. Valikhanov swallowed, and his sharp Adam's apple rose and immediately fell...

The caravan's path along the alley of death was dreadful. The cages, hanging from thin ropes, swayed in the gusts of wind, and there was nowhere to look without seeing the shriveled, shrunken, and sun-darkened heads... A sweetish smell of decay, mingling with the scents of dust and horse manure, made Valikhanov barely wrinkle his nose...

The caravan entered Kashgar at noon on October 1, 1858, crossing the bridge over the moat and passing through the triple wooden gates. Valikhanov saw before him low flat-roofed houses made of clay, surrounded by walls, over which dusty branches of fruit trees swayed, and narrow dirty streets. The streets were so narrow that only one two-wheeled cart could pass along the central one leading to the bazaar. This same central street housed merchant shops, tea houses, barbershops, caravanserais. Here and there, woven mats made of chiy were thrown from roof to roof—for shade.

Musabay, Valikhanov, and their companions stopped at the "Andzhan" caravanserai.

Elder Nasir ad-Din continued to patronize the caravan, but this only heightened the suspicion of the Chinese officials. They carefully examined all the baggage and sent samples of goods to the amban—Chinese government official.

One of the higher officials, Dorga-Bek, despite the elder's protests, demanded the caravan-bashi to come to him.

Valikhanov, deciding that it was better not to hide and to go through all the trials at once, went with him. Dorga-Bek questioned them for a long time about the route, the goods, and the purpose of their visit. They left him worried, hoping in their hearts that the interrogations would end there. But the next day they were summoned to the amban himself, a wise and perceptive man, and they understood that all previous inspections and interrogations were only preliminary investigations... Musabay truly panicked, and Valikhanov felt little better.

Quickly saddling their horses, they followed the beks. Exiting the city gates, Musabay and Valikhanov saw tents near which stood strange structures resembling gallows. They were led into a spacious tent where four mandarins sat—two with red balls on their hats and two with blue ones. Those with red coral balls were the higher authorities—one amban, the other hakim-bek. Joining their palms and pressing their hands to their chests, but not daring to raise their eyes, Musabay and Valikhanov greeted the amban and hakim-bek. The amban examined them for a long time, intently, and no one interrupted him with questions or movements. The tent swayed slightly in Valikhanov's eyes, and he felt as if the minutes were heavily falling to the ground...

Finally, the amban said in Chinese: “These are neither Russians nor Tatars: the elder spoke the truth—they are Andzhanites.” His face lost its severity, and he spoke calmly and kindly. The caravan-bashi, having composed himself, successfully answered the questions, and as a farewell, the amban wished them good trade.

After the meeting with the amban, they were no longer interrogated, but both Valikhanov and Musabay constantly felt that secret surveillance over them continued...

In the coming days, Valikhanov understood why Kashgar, like other cities of Little Bukhara, enjoys such a loud reputation in the East...

The laws of Islam are harsh. The Quran forbids drinking wine, women are expelled from society, locked in harems, and are not allowed to show their faces to strange men. For adultery, the guilty women are stoned to death... In Bukhara, in Kokand, after the call to prayer, the police drive everyone into the mosques. Special spiritual officials walk the streets, followed by servants carrying sticks. These officials have the right to stop any passerby and check if he knows the Quran, and in case of error, immediately punish him on the street with sticks...

Kashgaria is a different matter, this unique oasis in the Muslim world. No one drives the faithful into mosques here; wine, hashish, koknar, opium are sold openly everywhere, and women enjoy complete freedom: they participate in feasts alongside men and can, if they wish, divorce an annoying husband without fear.

That is why polygamy, so characteristic of other Muslim countries, is extremely rare in Kashgaria: Kashgar women do not tolerate rivals in their own homes.

There is a strict custom in Kashgaria, sanctified by centuries of tradition: every foreigner who comes to the city is required to temporarily marry a chaukhen—a young woman specifically designated for this purpose.

A foreigner only needs to go to the bazaar, where free chaukhen gather in anticipation of a new husband, and choose a temporary companion to his liking. The conditions of these marriages are simple: without any delays, you will be married according to all the rules of Sharia, and upon departure, you will be divorced, with the only requirement for the husband being to feed and clothe his wife...

Accustomed to completely different life rules, Valikhanov was very surprised when Musabay said that they needed to go get married. Valikhanov tried to joke it off, but Musabay immediately became serious—failing to comply with the custom meant revealing oneself.

Valikhanov recalled the beautiful women of Omsk, to whom he had recited the poems of Polonsky and Maikov in the house of Gutkovsky, and laughed. What a story!.. No, he loved no one, made no vows of fidelity, but he had not even thought of marriage, even a temporary one!.. The situation he found himself in now seemed to him extremely comical. So, if now, when he, dressed in a Bukhara robe and tying a turban around his head, went out into the street and was asked where he was going, he would carelessly reply— to the bazaar, to get a wife... Once again, Valikhanov mentally transported himself to Omsk, to the circle of his officer friends—how they would laugh when he told them about this spicy adventure!

Musabay was waiting, slyly glancing at Valikhanov. It was clear that he had definitely decided not to postpone the wedding.

They went to the center of the city, to the bazaar square "charsu," which is located right next to the registan—

the main mosque. The carts creaked, golden dust swirled in the air, raised by hundreds of feet, donkeys brayed loudly, horses neighed, sheep bleated, swarms of fat bazaar flies buzzed annoyingly, and a multilingual crowd was colorful, moving, and noisy... What a variety of goods the merchants displayed and how they praised them, how insistently they called out to buyers!..

It smelled of hot dust, sharp sauces, raw meat (the flayed carcasses of rams, blackened by countless flies, hung everywhere), horse and sheep manure, sour dried apricots...

Musabay confidently made his way to that part of the bazaar where, according to his calculations, the chaukhen spent their time; agitated, feeling curiosity and embarrassment, Valikhanov obediently trailed behind, peeking out from behind the broad back of the caravan-bashi...

And they saw the chaukhen, dressed in silk cloaks with golden ribbons; their long white veils were thrown back, and their faces remained uncovered. Without a hint of embarrassment, they examined the passing men, chatted, and laughed after them...

Then Valikhanov felt that everything happened without his participation: he simply saw before him a sweet, slightly pockmarked face and caught the scent of cosmetic hemp oil and garlic, with which the Kashgaris season their food; the slanting, piercing black eyes looked at him with a hint of mischief, but with affectionate submission; the chaukhen said something, and between her pink lips gleamed even white teeth...

In the evening, the caravan-bashi arranged a mashreb for numerous acquaintances and relatives. The relatives of Alimbay were also present at the mashreb—they suspected nothing and accepted Valikhanov as one of their own; even an elderly grandmother sent him a gift... The guests—both men and women—sat on colorful carpets woven from the wool of fine-fleeced sheep raised in the high pastures of Kunlun, ate rich pilaf with lamb, raisins, carrots, and umach—a corn jelly with dried apricots, drank wine, buzu, listened to melodic but monotonous music, to which the flexible and graceful "aga" dancers danced, and then all the guests joined in...

And when the guests left and Valikhanov was left alone with the chaukhen, he again turned into a Kazakh officer, raised in a different environment, with different, far from local, notions of honor, love...

And the eighteen-year-old chaukhen, who had first married six years ago, curiously observed this young, slender Aydzhan—her new husband...

The Great Journey of Chokan Valikhanov. Part 4