Kyrgyzstan "integrates" into China's giant plans

Expert: Kyrgyzstan "integrates" into China's giant plans

On December 27, trilateral ministerial negotiations on the construction of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway will take place in Tashkent. The day before, Kyrgyz President Sooronbay Jeenbekov instructed Minister of Transport and Roads Jamshitbek Kalilov to thoroughly prepare an expert group, as "the railway project is very important for Kyrgyzstan to access external markets." Jeenbekov emphasized that the prompt start of construction would enhance Central Asia's attractiveness as the most advantageous and effective transit corridor in the region.

The initiative to build the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway has been periodically voiced since the early 2000s, but it has not progressed beyond discussions. According to estimates from 2012, the construction of this railway will require $6-6.5 billion.

It should be noted that before the construction of the railway from China to Uzbekistan begins, a similar project for a road has almost been implemented, which is referred to in Kyrgyzstan as the "Alternative North-South Road," concealing under this neutral name a de facto Chinese transport project. What is the significance of this road, and why has the implementation of the railway project itself not yet begun? EADaily answers these questions with independent economist Kubat Rakhimov.

It probably makes sense to start from afar. During the Soviet years, the issue of connecting the northern and southern parts of the Kyrgyz SSR could not be acute, as everything occurred within the framework of a single national economic complex. There was one country, and how to transport, say, goods from northern Kyrgyzstan to the south—through some regions of the Tajik SSR or Kazakh SSR or via the internal Bishkek-Osh road—did not matter. The first president of Kyrgyzstan, Askar Akayev, deserves credit for immediately recognizing the problem of regional connectivity after the collapse of the USSR and took care of reconstructing the Bishkek-Osh road. This is the key lifeline of modern Kyrgyzstan, including from the perspective of military logistics or logistics related to maintaining law and order. The two revolutions of 2005 and 2010 showed that the rapid deployment of special forces, security services, and military personnel in Kyrgyzstan is only possible by air. In Kyrgyzstan, there is a term OBON—"Special Purpose Women's Unit." This "unit" knows exactly how to paralyze the country if necessary—where to set up yurts to block communication, where to close the highway. Within hours, trade, passenger communication, and everything related to it begins to take on crisis characteristics. Additionally, the highway itself is overloaded, the pavement wears out quickly, plus there are traffic jams at the Too Ashuu pass. All of this hinders sustainable traffic.

At that time, Kyrgyzstan faced a dual task: to ensure the connectivity of the country but with minimal costs. The first option was to reboot relations with neighbors—Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan—and ensure absolute and unobstructed transit for goods traveling on their roads. However, apparently, Kyrgyz diplomacy considered this task unmanageable. The second option was to build a railway that would connect the north of the country with the south and simultaneously become a transit route for China, the Near East, and Southern Europe. Bishkek believes that only the Chinese can do this. However, building a railway is a long-term project. Therefore, a third option emerged, the most acceptable for the authorities. This concerns an additional road route between the north and south, dubbed the "Alternative North-South Road." China readily responded to this idea, kindly offering a concessional loan from the Exim Bank. It includes a high component of so-called grant support. The loan was eagerly accepted, and the first tranche was quickly utilized. But soon, either appetites grew, or other problems arose, and today the progress in road construction is modest.

Will the initiated project be abandoned?

Kyrgyzstan currently cannot afford large borrowings, including for the completion of this road. The situation is not the simplest. The early write-off of Kyrgyzstan's debt to Russia amounting to $240 million or 3.8% of the country's total external debt will go towards new borrowing. The new loan for the completion of the road will be taken from China. Moreover, half of the road has already been built, more or less.

What benefit does China gain from these combinations?

Beijing has realized that it is not easy and straightforward to build a railway in Kyrgyzstan for several reasons. The first is that Bishkek has nothing to pledge, and without state guarantees, China is unwilling to lend money. The railway costs $6-7 billion, while the road along practically the same route costs no more than $1 billion. The second reason is the unstable country from the perspective of governance: staff turnover, constant changes at the top—they do not even have time to remember our prime ministers. The third is the restless local population. The construction of a railway typically touches sensitive points—these include pastures, agricultural land, and possible demolition of houses or even entire settlements. Moreover, in southern Kyrgyzstan, land issues are considered extremely sensitive. Finally, building such a large transcontinental road makes sense only when there is a cargo base, i.e., when there is something to transport, and this is sparse in Kyrgyzstan. Therefore, China took a pragmatic approach; it is easier to build a road. First, Kyrgyzstan easily takes loans; second, construction can be easily divided into sections; third, the loan has a high grant component, which makes the project extremely attractive for the elites. And perhaps most importantly: the pragmatic logic of the Chinese is that this alternative North-South road, which will connect routes from Kashgar (China) through Turgart (China) towards the Fergana Valley, will demonstrate the future cargo base and show the parameters of profitability for the future railway.

So, does China still need the railway?

The population of Urumqi—the capital of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region—has exceeded the entire population of Kyrgyzstan. There are already more than 7 million people there, while Kyrgyzstan has 6 million, considering those who have gone abroad for work. There are also serious growth points in Kashgar. A powerful industrial zone has been built around Kashgar. For the past 10 years, China has been purposefully relocating a significant industrial base there. By moving the industrial base westward to Xinjiang, the Chinese are addressing the task of industrializing Xinjiang and shifting the focus of the human flow there. For example, Han Chinese need to move to the western region to "dilute" the local population—Uyghurs and other small ethnic groups. All of these are elements of one big Chinese game. Plus, there is the economic aspect, which is beneficial for Beijing. Banks lend not to the state but receive guarantees from foreign states; money hardly leaves China, remaining 80-90% with Chinese road companies that build this road, pay wages in yuan to their workers, and buy their own Chinese construction materials.

What is the economic sense of the automobile "Alternative North-South Road"?

It lies in ensuring the future cargo base for the potential railway project. In strengthening China's commodity expansion in the densely populated Fergana Valley. In developing cross-border routes from China through the territories of Central Asian countries to Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkey. In the ability of Chinese companies to ensure uninterrupted logistics for joint ventures that they have already opened in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. I would also like to point out that the Chinese have reached such a level of costs that it is normal for them to transport ore from Kyrgyzstan's deposits by road. China is pursuing a long-term strategy for developing those deposits that they have not accessed due to a lack of communication. But now such an opportunity is emerging. And after the development of the deposits begins, there will be a stratification into profitable, moderately profitable, or highly profitable deposits. Only then will there be a high probability that they will actively promote the construction of a railway for large-scale export of ores or to ensure the logistics of their mining and processing plants in the territories of Central Asian countries.

As for Kyrgyzstan, its tasks are more modest. After the road is ready for operation, it should be made toll, so that all revenues from its use go specifically towards repaying loans and maintaining the infrastructure in good condition for active transit use. This road, under normal circumstances, becomes the first stage for forming a cargo base for the construction of a railway. If, of course, it will ever be built.

Read also:

Olga Viktorovna Nikolskaya

Nikolskaia Olga Viktorovna (1948) Doctor of Technical Sciences (2000) Russian. Born in Frunze....

Korolkov's Sage / Korolkov Sage, Korolkov Kyok Bashy

Korolkov’s Sage Status: VU. A rare narrow endemic species. A highly decorative plant....

The International Business Council has developed a vision for the development of Kyrgyzstan's economy.

The International Business Council has developed a vision for the development of the Kyrgyz...

Giant Ktyr / Dёё sher chymyny \ Eversmann’s Giant Robber-fly

Eversmann’s Giant Robber-fly Status: Category III (LR-nt). A species that is rarely encountered...

Turkestan Smoke Plant / Turkestan Fumitory / Microfumitory

Turkestan fumitory Status: Category ENBlab(iii,iv). A representative of the monotypic [60,...

The world's first solar helioconcentrator with two towers launched in China

This solar power plant was created by China Three Gorges Corporation, known for constructing the...

The History of the Development of Przhevalsk - Karakol. A Look at the Past and Present

Dear residents and guests of the city of Karakol, the "VisitKarakol" project, in...

May 10 International Marathon "Run the Silk Road"

We invite you to participate in the 5 km marathon run (for amateurs: running and walking), which...

Enduro Motorcycle Journey in Kyrgyzstan. Enduro Kyrgyzstan

Motorcycle Journey Enduro Kyrgyzstan. Enduro Kyrgyzstan...

The Beautiful Country Known as Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan is a small country bordering Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Russia. The main attractions...

Kyrgyz Illusionists Conquered France

Kyrgyz illusionists have once again made a name for themselves. Radislav Safin and Olga Kramer have...

Manas Airport. Bishkek. Kyrgyzstan.

Airport Manas. Bishkek. Kyrgyzstan. Kyrgyzstan. Bishkek. Airport Manas...

Dwarf Ammopiptanth / Baibiche Chekey / Ammopiptanth Dwarf

Dwarf Ammopiptanth Status: EN. A rare species with a disjunctive range. One of two known...

Cheerful Kyrgyzstan - Веселый Кыргызстан

An alternative for the tourism video of Kyrgyzstan. This video was shown in Sochi, where our...

Dedicated to everyone who lived in Bishkek! Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, Kyrgyz Republic, city of Bishkek

Bishkek, Orto-Tokoy Reservoir. September, 2013....

Central Asia Games Show (CAGS)

The coolest gaming event in the Kyrgyz Republic! The Central Asia Games Show (CAGS) will take...

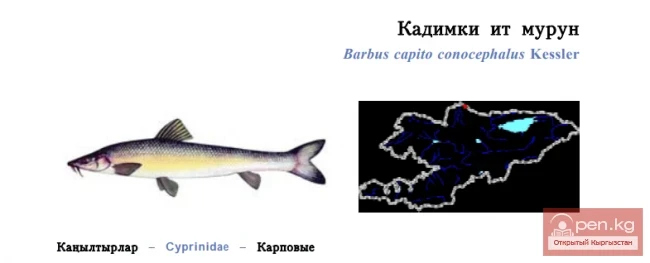

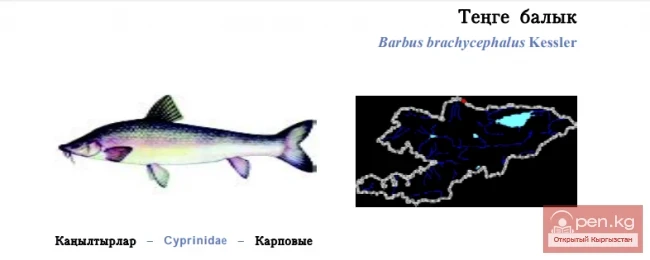

Turkestan Barbel / Kadimki It Murun / Turkestan Barbel

Turkestan Barbel Status: 2 [VU: D]. A subspecies that is endangered in Kyrgyzstan. One of...

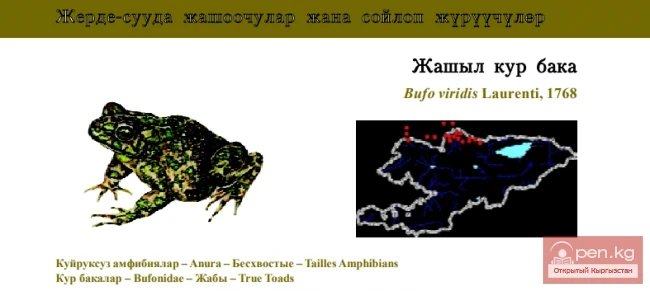

Central Asian Frog / Kyzyl Koltuk Frog / Middle Asia Wood, or Asiatic Brown, Frog

Central Asian Frog Status: Category VUB1ab(iv). A mosaic-distributed species with a disjunct and...

Minkwitz's Bastard Toad-Flax

Minkwitz’s Bastard Toad-Flax Status: CR. Subendemic. An extremely rare relict plant that is...

Sofora Korolkova / Boz Kempir / Korolkov’s Pagoda-tree

Korolkov’s Pagoda-tree Status: CR. The only species of the genus found in Kyrgyzstan....

Milan Expo 2015 Kyrgyzstan

The World Expo 2015 in Milan, unofficially "Expo 2015" (Italian: Esposizione Universale...

Stone marten or white-breasted marten / Suusar / Beech marten

Stone marten or beech marten Status: VII category, Lower Risk/least concerned, LR/lc. A rare...

Aral Catfish / Tenge Fish / Aral Barbel

Aral Barbel Status: 2 [CR: C]. Species extinct in Kyrgyzstan....

Bekmamat Murzakmatovich Dzhengbaev (1960)

Dzhenbaev Bekmamat Murzakmatovich (1960), Doctor of Biological Sciences (2001). Kyrgyz. Born in...

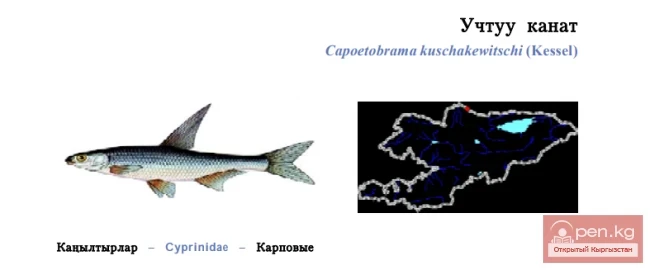

Chuya Sharp-wing / Uchtoo Kanat / Eastern Ostroluchka

Chuy Ostroluchka Status: 2 [CR: C]. Possibly already extinct in Kyrgyzstan, an endemic...

Beauties of Kyrgyzstan

Beautiful Kyrgyz women, winners and participants of beauty contests, models, actresses, and simply...

Upcoming Events for Lawyers from the British Company "Capital Business Events"

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen!...

In Russia, they have taken on cargo transportation: Almost 7,000 trucks from China, traveling through Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, have been stuck at the border with Russia for a month.

The main users of cargo transportation are marketplace sellers and small retailers. The cargo...

Andrey Krutko: "Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan Must Sit Down at the Negotiating Table"

Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan must sit down at the negotiating table, and together with the Russian...

Pasternak's Glacier / Miongu Pastinacopsis / Pastinacopsis

Glacial Pastinacopsis Status: EN. A rare endemic species of a monotypic genus in the Northern Tien...

Country of Kyrgyzstan, a Brief History

The country of Kyrgyzstan, a brief history...

The Show of Radislav Safin and Olga Kramer Conquers the Swiss Minute of Fame

Kyrgyz illusionists Radislav Safin and Olga Kramer received the highest score from the jury on the...

Turkestan Catfish / Turkestan Zhayany, Zhayany Fish, Lakka

Turkestan Catfish Status: 2 [VU: E]. The only representative of the genus in Kyrgyzstan....

Attractions of the Talas Region

Cities Talas...

Tourist Area Management Program

The project "USAID Business Development Initiative" (BGI), within the tourism...

The Secret to Radislav Safin's Success at Minute of Glory in Switzerland

"Kyrgyzstanis have once again proven that our country is rich in talent," reports the...

Attractions of Naryn Region

Historical-Architectural and Modern Attractions, as well as Natural-Ecological Complexes Cities...

International Championship International Beauty Championship

October 12-14 International Beauty Championship From October 12-14, 2018, the most anticipated and...

How the Image of the Kyrgyz Man Has Changed

100 years/ Style/ Kyrgyzstan. Limon.KG: How the image of the Kyrgyz man has changed...

New Wave 2014 - STYLE MIX (Kyrgyzstan)

New Wave 2014 - STYLE MIX (Kyrgyzstan) - World Hit...