Ancient Bactrian Glyptics of the Bronze Age

The symbolism and sign systems of the early medieval era represent a rich material and are actively researched by specialists. The analysis of artistic reliefs on ossuaries of the Biyanymen type is particularly indicative in this regard. The attributes of the depicted characters and a number of other specific features allow us to convincingly conclude that we are dealing with iconography related to the ufological layer of the Zoroastrian circle, regardless of whether the seven Amesha-Spentas are specifically reproduced here or some other circle of characters (Puganchikova, 1966; Grené, 1967). In Sogdian painting, if we refer to the artistic form of conveying information, one of the thematic blocks consists of scenes of worship to deities. Here, a stable image can be traced, such as a goddess on a lion with symbols of the sun and moon, known both in Sogdiana and in Khorezm.

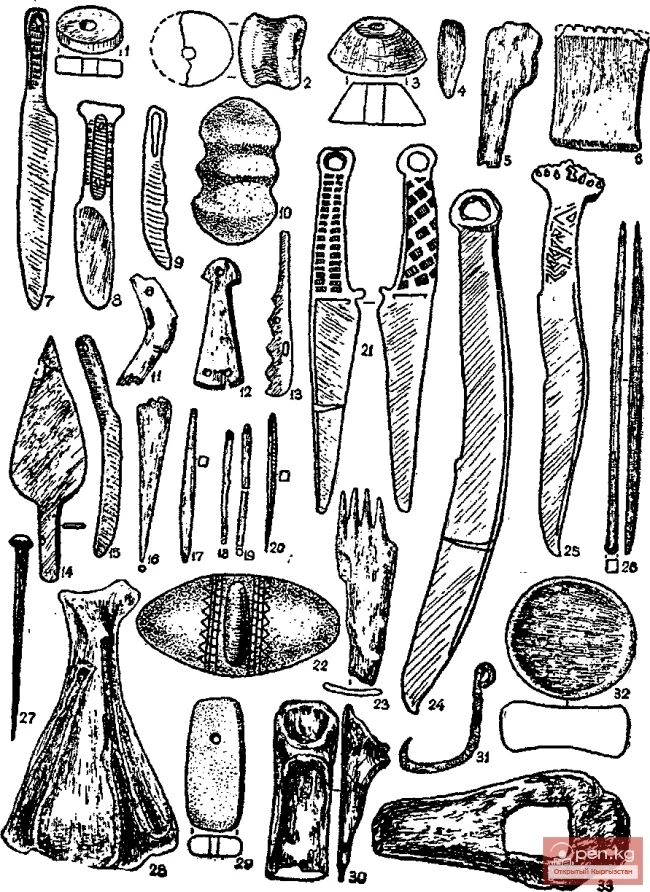

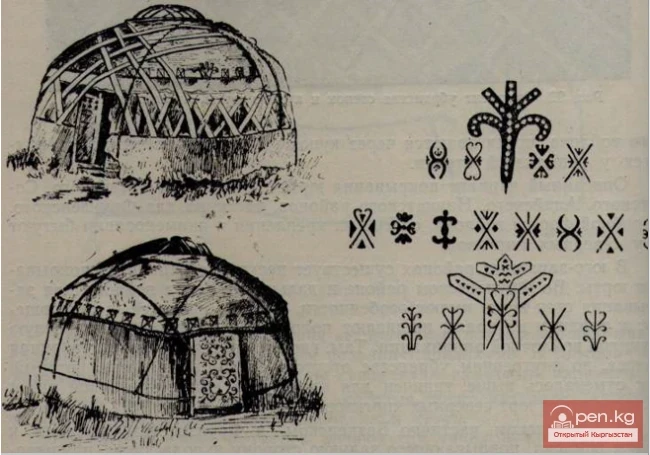

Deities associated with symbolism represented by animal figures—camels or horses, often incorporated into throne-like seats—were popular. There are three-headed and multi-armed nobility, bearing clear features of Shaivite iconography (Shkoda, 1977). A plausible assertion has been made that the female deity sitting on a lion reproduces Nana, known from Sogdian texts. However, no such image has yet been found with the corresponding inscription. The iconographic roots of this image go back centuries. In ancient Bactrian glyptics of the Bronze Age, there is a figure of a female deity sitting on a predatory feline. Overall, the issue of the deep ancient Bactrian layer in the ideological systems of Central Asia deserves special consideration. It is not so important whether to consider the religious concepts that existed then as proto-Iranian, as M. Pottier believes, or to approach this issue more cautiously, as P. Amié does. It is indicative, for example, that it was in Bactria that the image of a serpentine dragon was formed, which we later find (of course, through numerous transformations) in Panjikent painting.

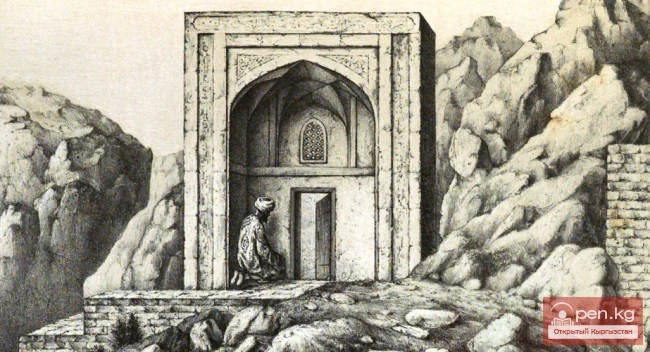

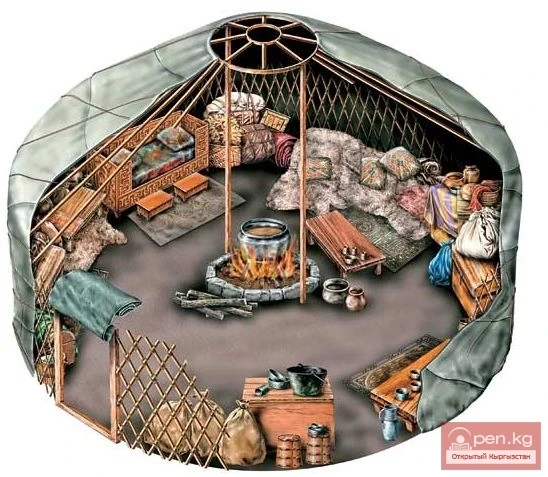

Written sources convincingly testify that the Sogdians were familiar with the Avesta, using many concepts and terms characteristic of Zoroastrianism. The ritual practice, as presented in archaeological and iconographic materials, indicates the preservation of a traditionally special attitude towards fire. It is noteworthy that in the temples of Panjikent, parts of burnt hearths, apparently rendered unusable, were not thrown away but carefully placed in special pits on the temple and temple-adjacent territory (Shkoda, 1986). The temples themselves had special rooms for storing fire. One of the characters depicted on ossuaries of the Biyanymen type holds a small shovel intended for scooping up sacred ash. The preservation of the ideological attitudes of the Zoroastrian circle in the mass psychology is also evidenced by the widespread practice of ossuary burial. All this allows us to consider the religious macro-system of this time, as well as that of ancient times, as a Central Asian variant of Zoroastrianism with a significant role of the fire cult ("fire temples" of Arab authors) and burial rites that involve deliberate cleansing of bones.

This macro-system can be most fully characterized by the archaeological materials from Sogdiana and the adjacent northern regions. The use of such terminology raises objections from researchers who believe (following the Sasanian magi) that true Zoroastrianism is represented only in early medieval Iran. However, even the first researcher of Panjikent painting, A. Yu. Yakubovsky, noted that there was no strict Sasanian dogma in Central Asia; Zoroastrianism was influenced by local cults that coexisted with the fire cult (Yakubovsky, 1964). A special term—Mazdaism—was even proposed for the religious beliefs of early medieval Central Asia (Stavisky, 1952). But I believe that the concept of "Central Asian Zoroastrianism," which has recently gained acceptance in specialized literature, is more successful and convenient.

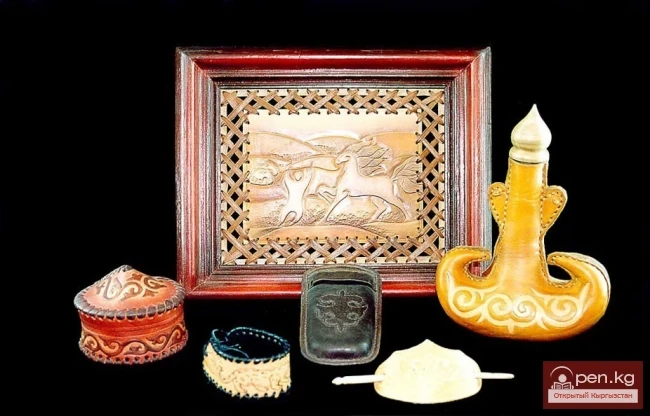

The specific features of the Central Asian religious macro-system have long drawn the attention of researchers. Such are the rituals associated with mourning the deceased. They were strictly prohibited by orthodox Zoroastrianism but are represented in the iconography of Sogdiana and Khorezm. Perhaps these rituals belong to the same circle of funeral ceremonies as the placement of coins, jewelry, and ceramic utensils in nauses of ancient times. Another distinction lies in the forms of worship of supreme deities. The orthodox iconoclastic position of the Sasanian magi is known. In Central Asia, on the contrary, images of various deities were venerated, their statues (often made of precious metals) adorned various temples; it is no coincidence that Arab authors speak not only of "fire temples" but also of "temples of idols." The reconstruction of the rituals practiced in the temples of Panjikent, in full accordance with the iconography, indicates the lighting of fire before the images of deities. Stable iconographic canons and sets of attributes in these images noticeably varied, reflecting, in particular, local specificity. There is a clear influence of foreign iconography, especially Indian. As F. Grené aptly noted, the Iranian basis is often difficult to discern beneath Indian plastic forms (F. Grené, 1987). Polytheism was a characteristic feature of religious beliefs in early medieval Central Asia.

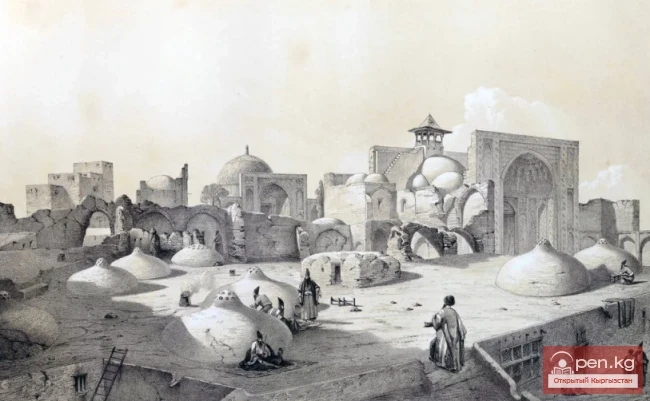

Thus, compared to the era of ancient civilizations, the early medieval period in Central Asia marks the formation of a more stable and, in some respects, more canonical ideological system. This is particularly evident in the Sogdian cultural complex, where, apparently, there are also ethno-confessional features, and the dynastic cult is weakly represented, which is quite natural in conditions of political fragmentation. The decline of Buddhism in Bactria correlates quite clearly with the destruction of a highly organized urban society. This stable ideological macro-system was undermined by the Arab conquest and overthrown during the subsequent establishment of Islam. The qualitative cultural and socio-psychological changes occurring in the countries subjected to active Islamization deserve special study, which is becoming quite relevant today, considering the so-called "Muslim Renaissance."

The Ideological Block of Ancient Central Asian Civilizations