50% of the Flora of Kyrgyzstan Consists of the Largest Number of Useful Species

Analyzing the distribution of useful species across families, we observe an interesting picture. Out of 115 families found in Kyrgyzstan, only 18 contain a more or less significant number of useful species (896). These same 18 families, in terms of the number of species (1720), make up almost 50% of the flora of Kyrgyzstan. Therefore, the families that are represented in Kyrgyzstan by numerous species also contain the largest number of useful species. The remaining families of useful species contain few—ranging from 1 to 10.

In some families, useful species have not yet been found. These include: Rubiaceae, Bladderworts, Orobanche, Potamogetonaceae, Santalaceae, Watercress, Frankeniaceae, Tailflower, Derbennikovye, Salicornia, Pyrola, Ericaceae, and others.

What is the reason for this phenomenon? Why are some families in the territory of Kyrgyzstan represented by numerous species and contain many useful plants, while others have few species and no useful plants?

There are many reasons for this phenomenon. However, perhaps one of the most important is the biological characteristics of the species and the patterns of accumulation of certain useful plastic substances under different ecological conditions.

A preliminary analysis of the flora of Kyrgyzstan showed that the accumulation of various plastic substances in different families occurs through different pathways and has its own specifics.

For example, in the family Lamiaceae, whose representatives are most characteristic of the deserts, semi-deserts, and steppes of Kyrgyzstan, the accumulation of essential oils occurs as an adaptation to xerothermic conditions—reducing transpiration. Of the 177 species of this family found in Kyrgyzstan, 36 species (almost 50%) produce essential oils.

At the same time, in other families, adaptation to xerothermic living conditions has taken a different path. For representatives of, for example, the Acantholimon family, Convolvulaceae (tragacanth bindweed), and Caryophyllaceae (spiny-leaved plant), adaptation to xerothermic conditions has occurred through processes of enhanced lignification of organs.

In Ephedraceae, xerothermic conditions cause a reduction in the assimilating surface (leaves) and a strong development of the root system, while in wormwood from the section Seriphidium, the process of adaptation to xerothermic conditions occurs through the development of a whole complex of traits—strong pubescence of leaves, production of essential oils, reduction of the assimilating surface, development of the root system, enhanced lignification processes, and others.

It should be noted that many representatives of the family Polygonaceae are tannin-producing. Of the 26 tannin plants found in Kyrgyzstan, 8 species belong to the family Polygonaceae, which accounts for about 30% of the tannin plants in Kyrgyzstan.

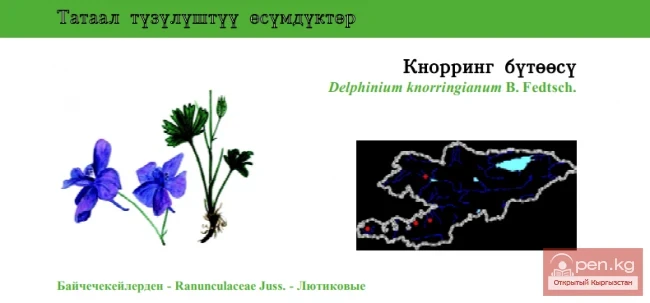

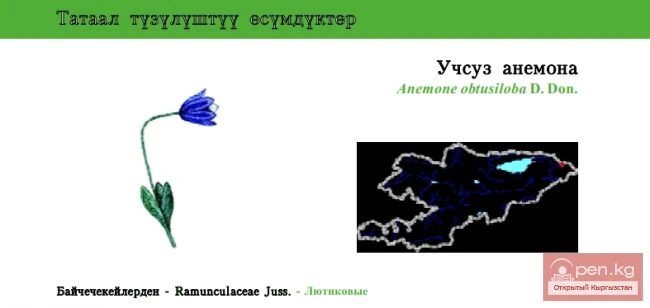

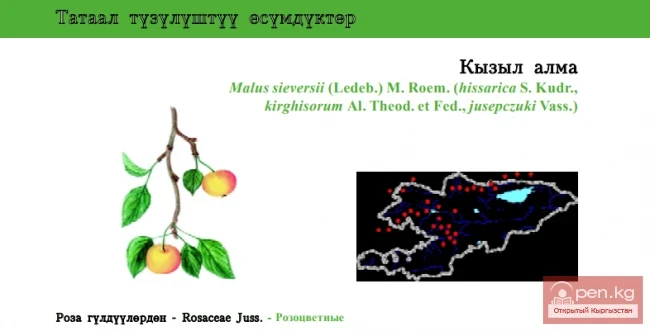

Almost all species of the family Ranunculaceae produce one or another alkaloids. Most representatives of the family Rosaceae are vitamin-producing, honey-producing, and edible. Among the Rosaceae, there are medicinal and tannin-producing plants. In general, this family is characterized by a large number of useful plants.

In the family Umbelliferae, there are many essential oil, resin-producing, and medicinal plants.

The families Cupressaceae, Pinaceae, and Juglandaceae in the conditions of Kyrgyzstan are almost entirely represented by phytoncide-producing plants, and these families occupy the lowest step in the evolution of higher plants. They stand on the first steps of the phylogenetic ladder of higher plants.

In the family Chenopodiaceae, there are many honey-producing and dye plants. Considering the family Poaceae, it should be noted that it contains almost 100% useful, mainly fodder plants.

As is known, grasses make up 70% of the herbaceous cover in steppes, about 40% in deserts, and 15-20% in meadows. Grasses form a significant biomass on our planet and are a highly plastic group of plants. They inhabit all zones and belts of the Earth, from the tropics to the tundra. Apparently, the accumulation of plastic substances of fodder value in plants occurs more intensively than other substances, as these substances are necessary for the life of the plants themselves. This gives grasses an advantage in the struggle for existence compared to other species.

Analyzing the family Amaranthaceae, it should be emphasized that this family is also characterized by the accumulation of plastic substances that have fodder value (tereskens, kochia, beets, orache, saltwort). However, amaranths also exhibit a whole series of interesting biological features—primarily unusual salt tolerance, which gives them an advantage in the struggle for existence among desert plants.

Amaranths, like grasses, stand on the lower steps of the phylogenetic tree of flowering plants. Hence, it can be assumed that at an early stage of the phylogenesis of angiosperms, species emerged that accumulated plastic substances of fodder value necessary for the life of the plants themselves.

Later, in the struggle for existence and adaptation to the environment, other plastic substances began to be produced.

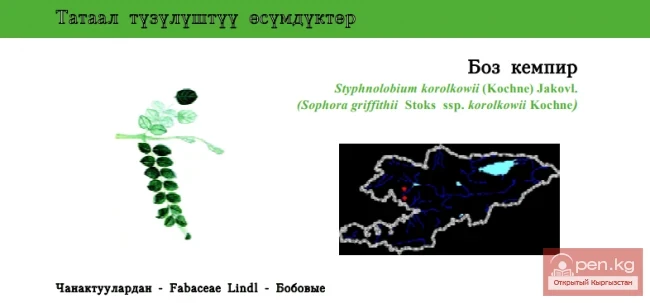

The family Fabaceae is interesting in that many of its representatives contain a large amount of proteins, and many are honey-producing, fodder, and medicinal.

The presence of fatty oils in the seeds is characteristic of representatives of the family Brassicaceae or Cruciferae. Alkaloids are characteristic of species of the family Ranunculaceae and Solanaceae.