Archaeological Materials of Central Asia

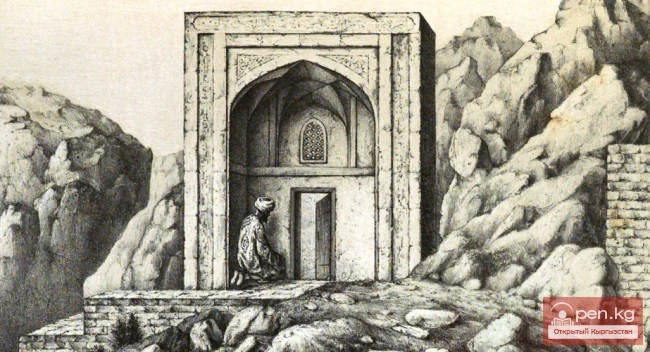

The reconstruction of ancient ideological systems based on material remains is one of the most complex issues in archaeology. Gordon Childe's biting remark that if something is unclear to an archaeologist, they declare it to be cultic is well known. In everyday archaeology, a simplified model of explanation predominates in the procedure: archaeological fact - primitively selected analogy - historical conclusion. The complexity lies in determining the informational capabilities of archaeology. Unlike written sources, archaeological objects were not created specifically for the storage and transmission of information. They are usually the material result, condition, or companion of the reconstructed processes and phenomena. The mass nature of archaeological materials currently allows us to pose the question of reconstructing not individual phenomena, but entire ideological systems reflected by groups of interconnected artifacts. It should be noted that archaeologists primarily have at their disposal objects related to cultic-ritual practices. Fire, kindled on the altar, for which incense was burned.

Ritual practices could be similar across various religions. Therefore, in historical interpretation, it is also important to use the significative function of culture, embodied in symbolism and sign systems as stable and recurring sets (sacred emblems, attributes of deities, etc.). The analysis of the artistic features of narrative works is of great importance for a more precise linking of cultic-ritual practices to religious systems of antiquity. In this case, the artistic form of storing and transmitting information, which plays a huge role alongside oral and written forms, should be utilized.

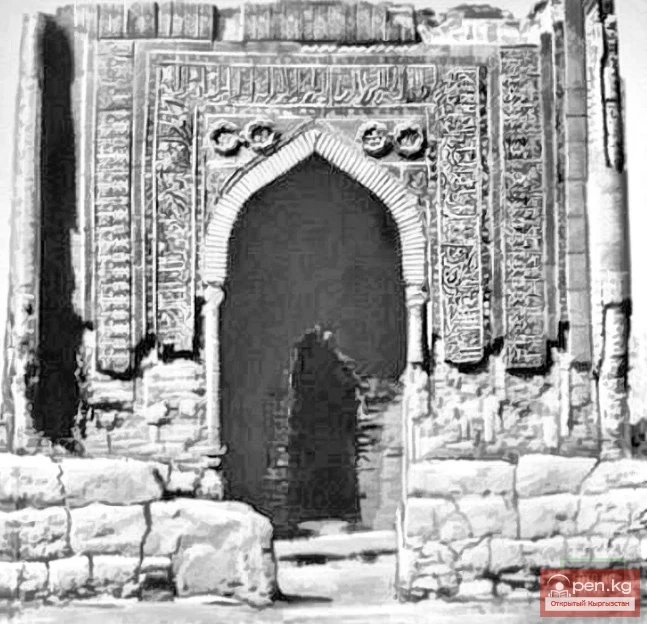

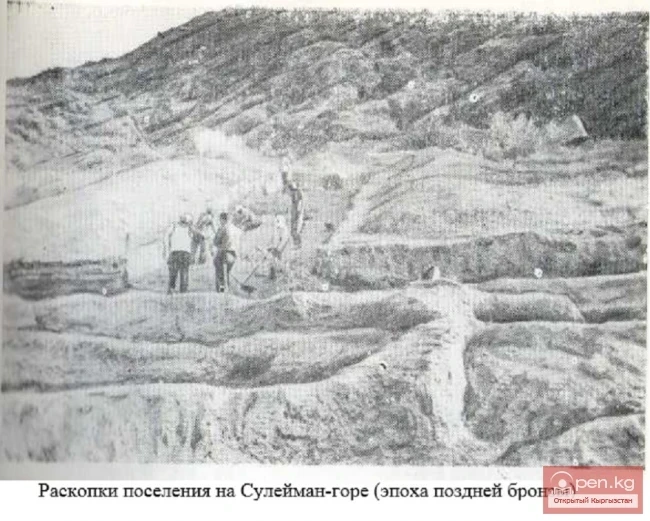

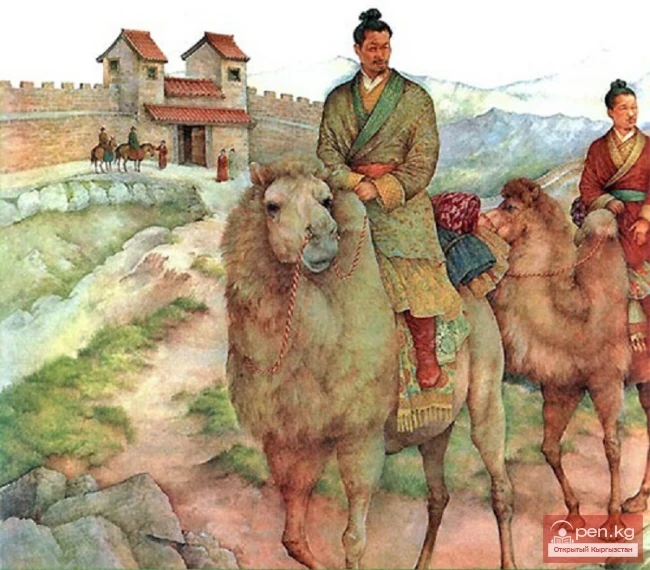

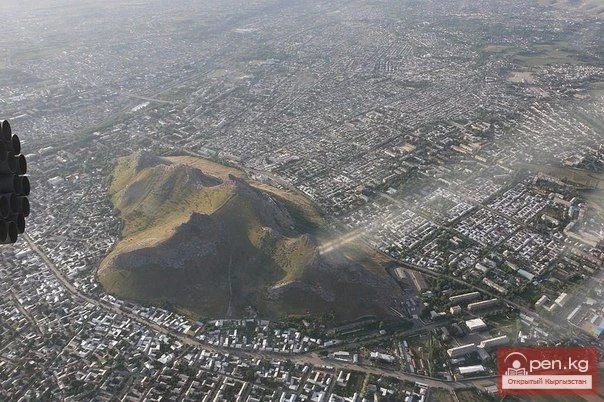

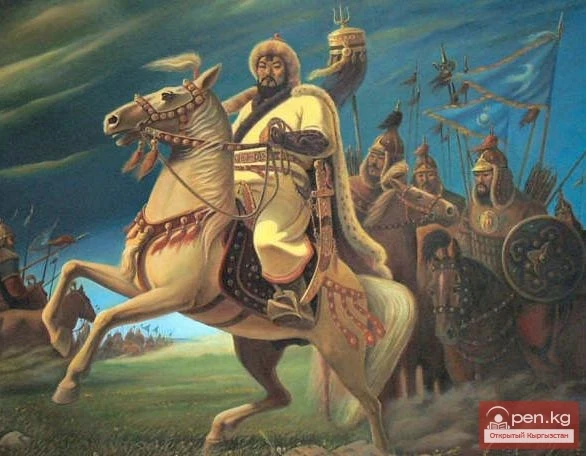

Let us consider the archaeological materials of Central Asia from these general positions, relating to two major epochs - the period of ancient civilizations and the early medieval period. The era of the flourishing of ancient civilizations in Central Asia - Bactrian, Sogdian, Parthian, and Khorezmian - spans from the 4th century BC and ends by the 4th-5th centuries AD. This was a time of the existence of large state formations (Greco-Bactria, Parthia, the Kushan state), targeted urbanization, and intensive processes of cultural integration, in which the Kushan cultural complex played a standard role for most settled areas of Central Asia. Cultural genesis is characterized by phenomena of spontaneous and stimulated transformation, reflecting active cultural interaction and cultural synthesis.

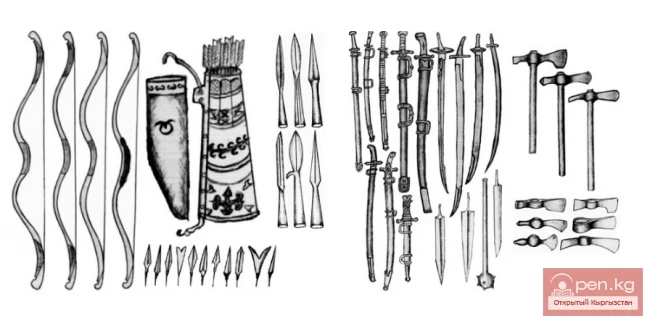

Among the sets of artifact types associated with the ideological system of this era, the set of types (from monumental architecture to terracotta and stone images) related to Buddhist materialized canons is most clearly explicable (Stavisky, 1977). It is primarily represented in Bactria, where it is a component of the Kushan cultural complex. These material standards of Buddhist doctrine were formed outside Central Asia, were primarily introduced here during the Kushan era, and have undergone little change related to local specificity, perhaps excluding the planning of cult complexes.

At the same time, there exists another set of artifact types, consistently widespread beyond any single civilization and reflecting, apparently, a kind of ideological macrosystem of regional scale. The ritual practice of this macrosystem is characterized by various terracottas, predominantly depicting female figures, domestic shrines with special altar-type structures (niches, hearths), incense burners, and monumental temple buildings with clear evidence of fire worship. On a regional scale, a specific burial rite is formed with burials in special structures (naus) of purified bones, often using special bone storage facilities - ossuaries. This set of stable artifact types is primarily represented and well-studied in Bactria and Khorezm, but component parts in one form or another have been identified in other centers of ancient Central Asia. Naturally, local specificity is noted in the variants that make up stable groups of types. For example, in terracottas, this is noticeable in the details of decoration, in the details of attributes, and sometimes in the very sculptural solution (Dalverzin, 1978).

The Sphere of Spiritual Production in Ancient Central Asia