“Prolonged” trip and letters to Bush

Utkur Rahmatullaev has been living in the USA for over 25 years. He first arrived in 2000 on a tourist visa for three months, after which he stayed in the country illegally.

“At first, I had no intention of staying. But seeing the standard of living here, it became difficult for me to return. For example, in those years, I sent my parents in Samarkand between 1000 to 2000 dollars, but they had to pay a bribe of 100–200 dollars to receive the money in the bank. This was a shock for me, as in America I could withdraw money anytime without any problems. In the end, I decided to stay,” he shares.

He spent the first five years in the USA without documents. In 2005, to legalize his status, Rahmatullaev decided to join the army. He had always dreamed of serving in the military.

“In Samarkand, we didn’t have a military department, but I really wanted to. In the early 2000s, 200 dollars in Uzbekistan was considered a significant amount, and many paid such bribes to avoid conscription. I wanted the opposite, but I was denied due to a law that did not draft the only son,” Utkur recounts.

When his applications to the US military recruitment offices were rejected due to a lack of necessary documents, Utkur began writing letters.

“I wrote to President George W. Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, senators, highlighting my language skills and desire to serve. My letter was forwarded to the Department of Defense, and soon I was called for an interview, where I successfully passed the language tests,” he explains.

Despite lacking formal status, he was accepted into the army. His language skills were in demand amid the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

“If you can be of benefit to the country, exceptions can be made. My father is Tajik, and my mother is Uzbek, so I speak Tajik and Uzbek, which was useful for understanding the culture and customs in Afghanistan,” Utkur clarifies.

Long-awaited citizenship and deployments to Afghanistan

Six months after joining the service, he received American citizenship and spent a total of 11 years in the army, having been deployed to Afghanistan twice.

The first deployment in 2007 was relatively calm — he worked in the personnel department and did not leave the base.

On his second deployment in 2014, he was assigned to a special unit.

“There were moments when I thought I wouldn’t return. We were in a village, interacting with locals, providing assistance, when suddenly the shelling began. I noticed that it wasn’t raindrops, but bullets. One of them hit the sand near my foot,” Utkur recalls.

According to him, after that incident, he did not realize the seriousness of the situation.

“Returning to the base, I saw that my room had been hit by a rocket. At first, I laughed, but then I thought: what if it had hit me?” he shares.

In the most dangerous situation, he found himself on the night of Laylat al-Qadr during Ramadan when his base was shelled continuously.

“Our air defense could detect threats from a distance, but when fired upon from 1–2 kilometers, it reacted too late. I thought this time I would definitely die. In such moments, you reflect on your entire life. I regretted being in Afghanistan. What am I dying for? Who will remember me?” Utkur ponders.

Return to the homeland and interrogations of relatives

After his first and second deployments, Utkur also worked in the military department of the US embassy in Tajikistan.

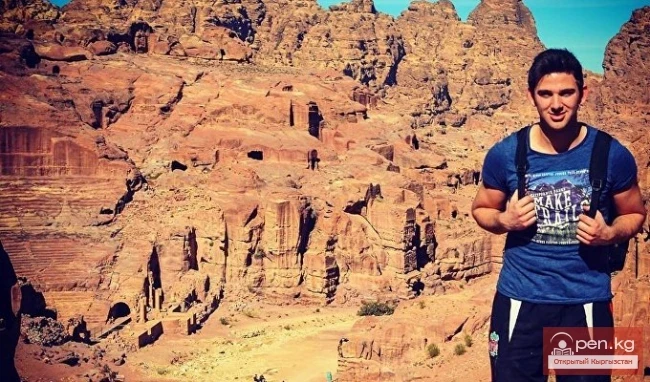

Utkur visited Kyrgyzstan several times and for the first time in 13 years, Uzbekistan.

“During the rule of [the late president of Uzbekistan Islam] Karimov, it was difficult. People returning from America were called ‘enemies of the people.’ After [President Shavkat] Mirziyoyev came to power, it became easier. When I arrived at the border, the border guard, taking my American passport, said: ‘Rahmatullaev Utkur Hikmatullaevich, you’ve really returned?’ I thought about whether I should go in, but I decided to do so since there were American diplomats nearby,” Utkur says.

He visited his native Samarkand and met with relatives, after which he learned that they had been summoned for interrogations.

“They showed them my photos from Afghanistan and asked if they knew me. I know that my friend was beaten, and he called me in fear,” he shares.

According to Rahmatullaev, the interrogations of his relatives began during Karimov’s rule and continued after Mirziyoyev came to power.

“My friend, who was interrogated during my visit, now lives in America. But there are others who were interrogated under Mirziyoyev,” Utkur adds.

He claims that the authorities of Uzbekistan have not brought any formal charges. Utkur hired lawyers to find out the reasons for the persecution of his relatives, but the lawyers soon stopped responding.

He also contacted the Uzbekistan embassy in the USA.

“I asked if I could return. They replied that I could not. They said: ‘You know, if you return, there is a case against you. You served in the US army. You could be imprisoned.’ I replied: ‘I am ready to take responsibility if that’s the case. I am not going to sit in prison for life,’” he recounts.

Now Utkur lives with his family in New York and does not rule out the possibility of returning to Uzbekistan.

“Before Afghanistan, I thought everything could be solved with money. But there, on the edge of life, I realized that it is not so. My views have changed. Many Uzbeks think: ‘I will earn in America and return to Uzbekistan in old age.’ I plan to do the same. I worked in the army and the embassy; I can be useful to my country,” Utkur assures.

(Not) punishment for serving in a foreign army

It is unclear what punishment awaits Utkur Rahmatullaev upon his return to Uzbekistan. Azattyk Asia was unable to contact the press service of the state security for comments.

According to Uzbekistan's legislation, citizens are prohibited from serving in the armed forces of foreign states. Under Article 154 of the Criminal Code, military service can lead to imprisonment for up to 5 years. In the past, Uzbeks who participated in conflict zones in the Middle East were prosecuted under this article.

After the start of Russia's war against Ukraine, calls from the authorities for citizens not to join foreign armies have become more frequent. However, according to the Ukrainian project “I Want to Live,” in 2025, at least 902 citizens of Uzbekistan signed contracts with the Russian Ministry of Defense.

Some of those who fought on Russia's side have been convicted in Uzbekistan on charges of mercenarism. Observers note that instead of real prison sentences, many receive restrictions on freedom or suspended sentences, possibly to avoid displeasing the Kremlin.