Carpet Weaving among the Kyrgyz

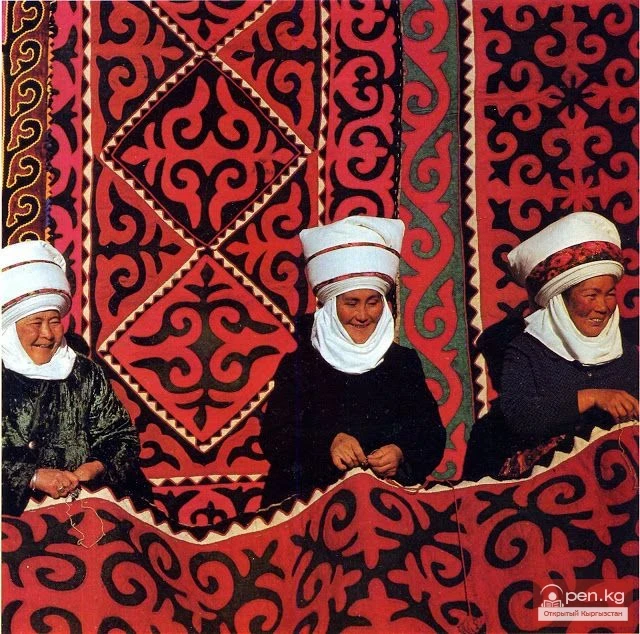

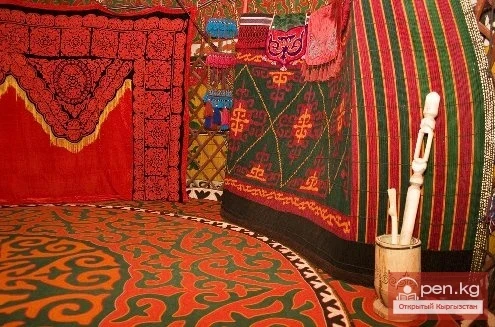

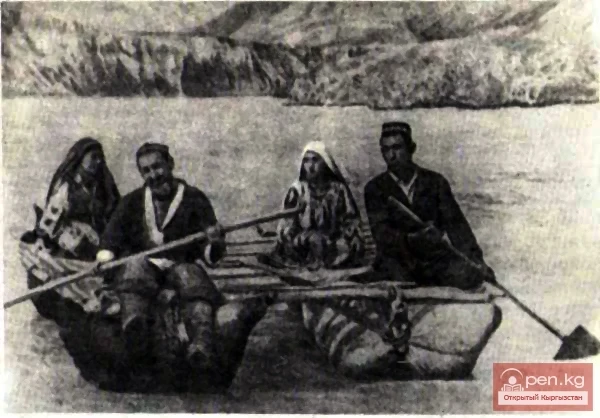

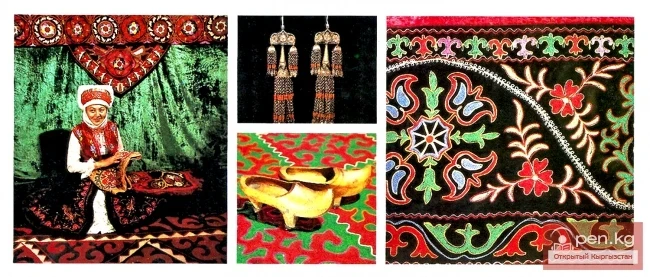

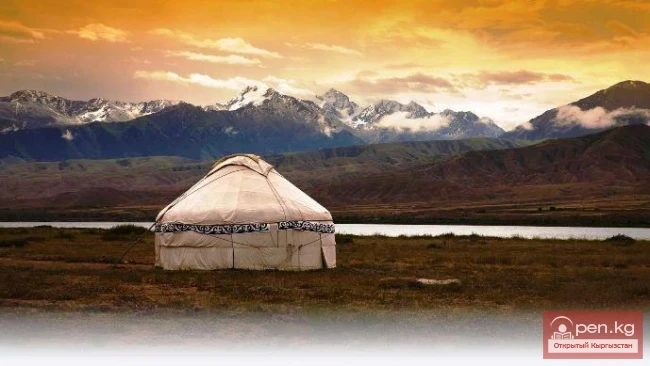

In the 19th century, especially in its second half, carpet weaving in southern Kyrgyzstan was widespread and was entirely in the hands of women. Originating from the needs of nomadic life, carpet weaving among the Kyrgyz initially developed in conditions of semi-subsistence farming, characterized as home production intended to meet the needs of individual families. However, even at that time, carpet products were mainly acquired by the upper class of society—the Kyrgyz nobility.