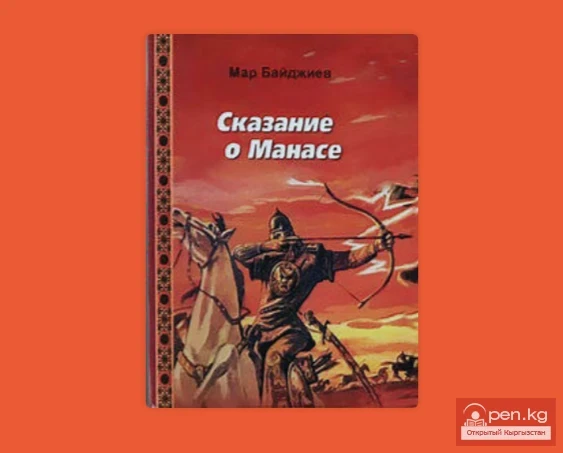

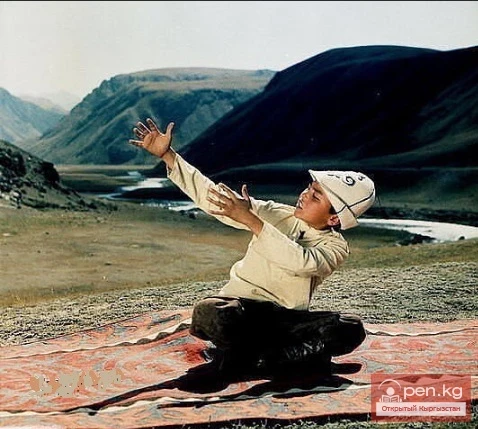

Tashim Uulu Mar — the first Russian-speaking Manaschi

[h2]About the poem "The Tale of Manas".

The creative individuality of the writer is most vividly manifested in the poetic vocabulary — the lexicon of the work. The foundation of "The Tale of Manas" as a Russian-language work is, of course, Russian vocabulary. It is presented, as required by the laws of the folk epic, in various speech variants (everyday, colloquial, military, jargon, etc.) and different stylistic layers (common vocabulary, conversational, vernacular, elevated, emotional, etc.).

In "The Tale of Manas," where, metaphorically speaking, heroes and warriors coexist organically, the author's active use of two speech layers draws attention — Old Slavic words (zlatо, glas, polon, kryla, zertsalo, pred, etc.) and colloquialisms (patsan, starshoy, baba, tysyacha, obaldel, etc.). Both of these layers are artistically motivated: Old Slavic words associatively lead the reader into the depths of epic time, while colloquialisms bring the epic heroes closer to our modernity.

Kyrgyz vocabulary in "The Tale of Manas" is mainly represented by proper names — anthroponyms (names of people), zoonyms (names of animals), toponyms (names of geographical objects), ethnonyms (names of ethnic groups), mythonyms (names of fictional objects in myths and fairy tales) and everyday vocabulary that is unknown or little known to the Russian reader in Kyrgyzstan (ashpozhchu — cook, tavak — wooden dish, chylbyr — horse's lead, tentek — rascal, nike — marriage ceremony, dobulbas — battle drum, surnay — zurna, flute, etc.). Translations of such words and expressions are provided partially in the text of the work and partially in the dictionary attached to it.

And finally, about the poem "The Tale of Manas". M. Baidzhiev, who, by the way, is the author of several works on Kyrgyz versification, faced a difficult question: what meter to use to convey the verse of "Manas," consisting of seven to eight-syllable syllabic lines? After all, in Russian versification, syllabics (the presence of the same number of syllables in a line regardless of the number of stresses) went into the past back in the 18th century after the reforms of Trediakovsky and Lomonosov, which established syllabotonic verse (a system of constructing verse based on the correct alternation of stressed and unstressed syllables). And Baidzhiev chose a four-foot iambic meter — a two-syllable meter with stress on the even syllables, which has become classical in the Russian language.

This is a very successful solution: first, the number of syllables in the line is almost preserved (eight); second, it takes into account the presence of a constant stress in the Kyrgyz language on the last syllable.

The tale of ancient times

Lives today, in our days.

A story without edge or end

The Kyrgyz people created,

Inherit from son to father

Passed from mouth to mouth.

In the rhyming of the verses, M. Baidzhiev achieved commendable adequacy. The poetic form characteristic of "Manas" is "djira" ("jyr"), which knows no regularity in the arrangement of rhymes. Here, stanzas are replaced by tirade groups of lines with the most diverse ways of rhyming. Thus, the text above has two tirade groups: a couplet with adjacent rhymes (aa) and a quatrain with alternating rhymes (abab).

Rhyme endings are repeated consecutively or intermixed with others in several lines: from three to ten to twelve. Often the rhyme arises unexpectedly — detached from previous homogeneous rhymes. Some lines do not rhyme at all. All these techniques enhance the artistic expressiveness of the verse, emphasizing the dynamism and continuity of the epic narrative.

A tale borne by the people,

Having gone through bloody years,

Sounded like a hymn of immortality,

Boiling in hot hearts,

Calling for freedom and victory.

To the defenders of the native land

This tale was a faithful friend.

Like a song carved in granite,

The people keep it in their souls.

With great poetic skill, M. Baidzhiev also uses other figurative and expressive means characteristic of the epic "Manas": redif and tautological rhyme, anaphora, assonance, alliteration, constant epithets, repetitions, parallelism, inversion, phraseologisms, etc. In other words, the poetics of "The Tale of Manas" is largely adequate to the poetics of the epic "Manas." This means that the Russian-speaking reader who comes into possession of M. Baidzhiev's book will gain a fairly complete understanding of the Kyrgyz epic, will be introduced to its themes, ideas, and images, and will enrich their spiritual and emotional world. At the same time, they will appreciate the book itself — bright, profound, innovative.

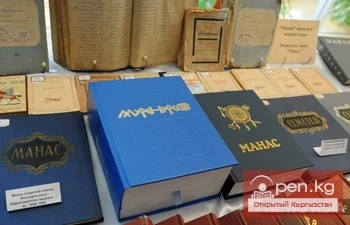

Thus, "The Tale of Manas" is a unique work, one of a kind. First, it is a poetic rendition of the first book of the trilogy — the actual "Manas" in its entirety, not just one episode, as in "The Great Campaign." Second, the translator-interpretator is a bilingual writer who does not need a literal translation. Third, "The Tale of Manas" is an original work created based on folkloric primary sources.

M. Baidzhiev's "The Tale of Manas" can be used not only for reading but also as a teaching aid for studying the epic "Manas" in secondary and higher education. In both cases, it is advisable to familiarize oneself with the introductory article by Academician B. M. Yunusaliev "The Kyrgyz Heroic Epic 'Manas'."

In the book "Tashim Baidzhiev," published in the series "The Lives of Remarkable People of Kyrgyzstan" in 2004, its author, Mar Baidzhiev, movingly recounts his visit to the prison cemetery of the former Karlag (Karaganda camp), where his father was buried in 1952. Standing by the nameless grave, the son mentally conversed with him:

“I served your 'Manas,' your native language. To the best of my ability, I did everything so that the great creation of our people would be known and admired by the whole world… As long as my heart beats and my mind works, I will continue your work. I swear before your ashes, at your grave.”

And Mar Tashimovich — Tashim Uulu Mar — remained true to his oath. By creating "The Tale of Manas," he became, metaphorically speaking, the first Russian-speaking Manaschi. With the release of his book, "Manas" enters the expanses of the Russian-speaking cultural and artistic space, gaining a new sphere of existence in a vast historical time.

The filial duty, bequeathed by God, is fulfilled.

The Traditional Feature of the Epic "Manas"

Read also:

Manas Airport. Bishkek. Kyrgyzstan.

Airport Manas. Bishkek. Kyrgyzstan. Kyrgyzstan. Bishkek. Airport Manas...

The Epic of "Manas". The Prayer of Manas

Prayer of Manas Almighty God! My Creator! I am on my knees before you. You gave us the sun above,...

The Epic "Manas". The Testament of Manas

Manas's Testament Embracing Kanike by the shoulders, He said to his beloved: — Be brave, my...

The Kyrgyzstan national team is preparing for the Eurasian Hockey Cup.

The Kyrgyzstan national team is preparing for the Eurasian Cup in hockey among children's...

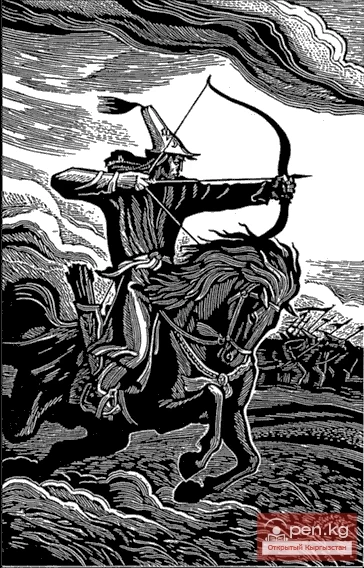

The Epic of "Manas". Shooting at the Golden Jamb.

Shooting at the Golden Jamba The return of the galloping horses, Will take seven or eight days....

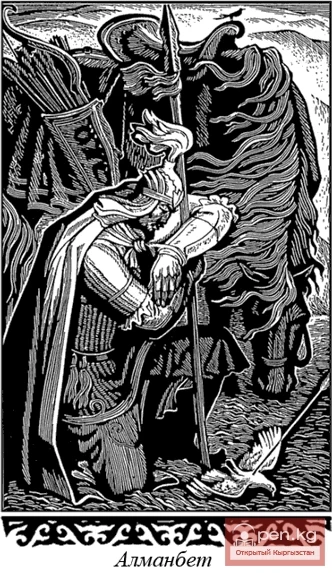

The Epic "Manas". The Tale of How Almanbet Came to Manas

The Tale of How Almanbet Came to Manas The khan Manas gathered the heroes And said: — I look at...

The Epic of "Manas": The Return of the Kyrgyz from Altai to Their Homeland

The Return of the Kyrgyz from Altai to their Homeland Under the banners of their clans Finally...

The Epic of "Manas". The Election of Manas as Khan

Election of Manas as Khan From the herd, where Aymanboz — A beautiful, strong stallion, Always a...

The Epic "Manas". A Review of the Horses

Horse Race Early in the morning, at dawn, As the green flag of Koketey Fluttered in the rays of...

The Epic of "Manas". The Conspiracy of the Kyrgyz Khans

The Conspiracy of the Kyrgyz Khans Hey! In the mountains, where the sunny Alay — The blessed land...

The Epic of "Manas". The Arrival of the Envoys to Manas

The Arrival of the Envoys to Manas Six envoys rushed From six noble clans On a long journey to the...

Announcement of the second part of the trilogy - "Semetey"

CONTINUATION OF THE EPIC: "SEMETEY" The death of the beloved hero, the sorrowful end of...

The Kyrgyz Epic "Manas" Will Be Translated into the Bashkir Language

The bearers of the Bashkir language will be able to familiarize themselves with the masterpiece of...

The Epic of "Manas": The March into Campaign and Victory over Tekes-Khan

The campaign and victory over Tekes-khan Hey! Two months have passed since We held a gathering in...

The Epic of "Manas". The Tale of How Manas's Relative Kozkaman Wanted to Poison Him with Poison

A tale of how Manas' relative Kozkaman wanted to poison him with poison Hey! The head of all...

Amazon-Rossomyrmex / Kara kursaktuu slave-holding ant \ Russian Rossomyrmex

Amazon-Rossomyrmex Status: Category II (VUB2ab(iii); C2b; D2). A rare relict representative of the...

The Epic of "Manas". The Victory of Manas over the Envoys of Esen Khan

The Victory of Manas over the Envoys of Esen Khan When the whole world was engulfed by a flood And...

Epic "Manas". The Beginning of the Battle. Part - 3

The Beginning of the Battle. Part - 2 Hearing the joyful news, Kanykey was not pleased: — Taking...

The Epic of "Manas". The Duel of Manas with Konurbai

The Duel of Manas with Konurbai The son of Koketey Bokmurun The latter announced the tournament. —...

Epic "Manas". Return from the Great Campaign. Part - 2

Return from the Great Campaign. Part - 2 When they passed the Great Wall of China, They settled...

The Epic "Manas". The Death of Manas

The Death of Manas At night, secretly Kanykey Gathered the loyal warriors, Far along the mountain...

Epic "Manas". The Beginning of the Battle. Part - 2

The Beginning of the Battle. Part - 1 From morning till night, the slaughter went on, And from...

The Epic of "Manas". The Death of the Heroes

The Death of the Heroes A rumor swept through China That Khan Manas was wounded. The spirit of the...

Epic "Manas". Invitation to the memorial for Koketey

Invitation to the Memorial for Koketey Here in the vastness of Karkyra, Setting up yurts with a...

The Epic of "Manas". The Tale of How Khan Alooke, Upon Seeing Manas, Fled from Fergana

A Tale of How Khan Alooke, Upon Seeing Manas, Fled from Fergana In the hands of the Chinese was...

The Epic of "Manas". The Arrival of Manas in Karkyra

The Arrival of Manas in Karkyra And exactly on the fourth day To the green shores of Kegen Came...

Epic "Manas". Return from the Great Campaign. Part - 1

Return from the Great Campaign. Part - 1 On one of the gloomy nights Kanykey woke up in tears,...

Comparative Analysis of the Plots of the Poem "Manas" by Sagymbay and Sayakbay

"Manas" as performed by Sagymbay and Sayakbay "Manas" as performed by Sagymbay...

The Epic of "Manas". The Attack of Neskara

The Attack of Neskar The ruler of the Manchus became Twenty-year-old Neskar — Hot-headed, bold,...

Epic "Manas". The Beginning of the Battle. Part - 1

The Beginning of the Battle Karagul rushed to the khan And informed Konurbai That the cunning...

The Epic "Manas". In Reconnaissance

In reconnaissance They came to the valley of Teshik-Tash, Where fragrant flowers Bloom on the...

The Epic of "Manas": The Meeting of Manas with Koshoy and Bakay

The Meeting of Manas with Koshoy and Bakay The celebrations had just ended, Akbalta called Manas....

The Epic of "Manas". The Tale of the Destruction of the Kyrgyz by Khan Alooke.

Tale of the Destruction of the Kyrgyz by Khan Alooke Hey! From ancient times the Kyrgyz people...

The Epic "Manas". The Tale of How the Afghan Khan-Shoruk Suffered Defeat from the Kyrgyz

The Defeat of Afghan Khan Shooruk by the Kyrgyz Hey! In the south, where Alay lies, And nearby is...

The Epic "Manas". The Love of Manas and Kyz-Saykal

The Love of Manas and Kyz-Saykal In Uch-Turfane lived Karacha — A glorious elder from Kalmykia....

Epic "Manas". The Great Campaign to China. Part - 1

The Great Campaign to China On the forty-first day in the morning On the argamak Ak-Kula Manas...

8 Thousand Lines of "The Tale of Manas" by M. Baidzhiev

Innovation of M. Baidzhiev What dramatic elements did M. Baidzhiev transform in 'The Epic of...

The Epic "Manas": A Tale of the Liberation of Turkestan from Chinese Invaders

Tale of the liberation of Turkestan from Chinese invaders Into valleys, mountains, and meadows...

The Epic of "Manas". The Tale of How Manas, Upset with His Father, Left the Khan's Throne

A Tale of How Manas, Offended by His Father, Left the Khan's Throne and Took Up Farming In...

The Epic "Manas". The Conclusion of the Mourning for Koketey

The Conclusion of the Mourning for Koketey On the eighth day, Bakai gathered The comrades and told...

From Improvisation of the Manaschi to Narrative Activity

Common form of performance for storytellers of "Manas" When comparatively studying the...

The Epic of "Manas". The Tale of How Almanbet Came to the Kazakh Khan Kokche

The Tale of How Almanbet Came to the Kazakh Khan Kokche Hey! Having fled from China, Almanbet...

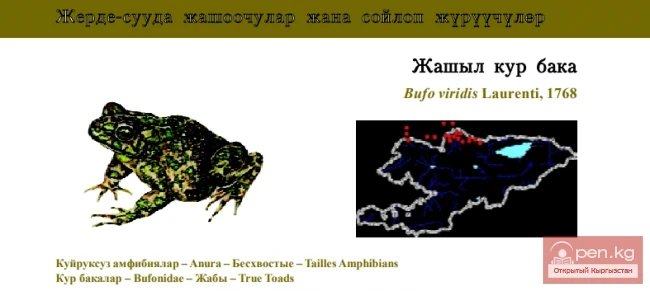

Central Asian Frog / Kyzyl Koltuk Frog / Middle Asia Wood, or Asiatic Brown, Frog

Central Asian Frog Status: Category VUB1ab(iv). A mosaic-distributed species with a disjunct and...

Territory, Geography, and Administrative Division of Kyrgyzstan

Territory, Geography, and Administrative Division of the Kyrgyz Republic The Kyrgyz Republic...