Childbirth

Pishpek District, Buraninskoye Village

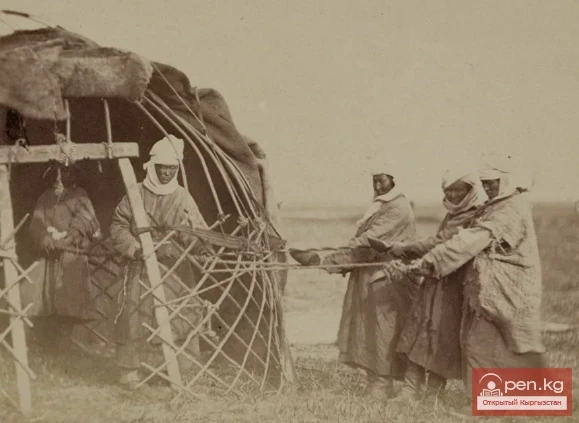

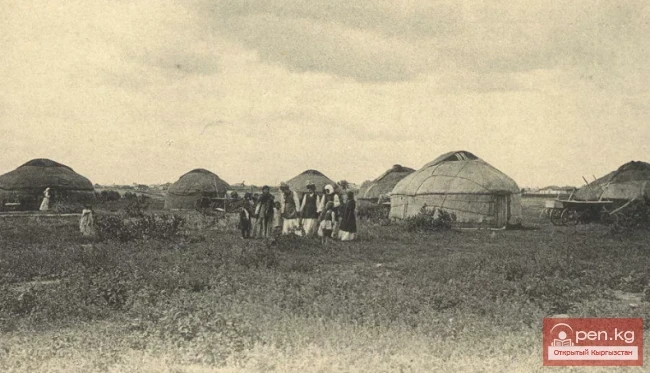

During childbirth, men can assist. If the woman lacks strength, the man stands behind her, wraps his arms around the birthing woman, and presses on her abdomen from above. A long stake is driven into the ground, and the woman kneels before it, holding onto it1, while using her hands to position the child in the womb. Scaring is not used.

If the afterbirth (placenta) is difficult to expel after childbirth, a person walks around the yurt and pounds it in a mortar2.

The afterbirth3 is thrown to a dog — it's better than burying it in the ground4. In difficult births, a mullah is called, who writes an amulet (tumar). The umbilical cord is cut by the kin-dik-ene — the mother of the umbilical cord5; the cord is tied off with a thread near the abdomen beforehand. The detached part of the umbilical cord is kept at home6.

If after childbirth the woman... (illegible. — B.K., S.G.) faints, water is splashed on her face or the mullah recites prayers (kuuchu7).

rch. Bolshoy Kebin

In difficult births, if the woman faints, it is said that her soul has been taken by the albarsty8. Then they call the kuuchu.

The father slaughters livestock. The afterbirth is buried in the ground wherever possible, away from the yurt. When the child is born, one of the men shouts: "Azan!" (call to prayer)9. When labor begins, one woman walks around the yurt with a mortar, striking it against the ground, saying: "Tushtu bo, tushtu bo?" ("Has the child come out, has the child come out?").

Zhanyzak

solto

The birthing woman washes after childbirth.

Food for the birthing woman

Talas

kainazar

On the first day, the birthing woman receives boiled milk, on the second — tea, on the third — porridge made from taru. On the fourth day, her husband slaughters a lamb and feeds her meat. If she is thirsty, the birthing woman drinks water.

Chonkur-Talas

kainazar

Kalzha — a nutritious meat meal given to the birthing woman by her husband, who has slaughtered a lamb10.

Mat'-pupok11

Pishpek District, Buraninskoye Village

The kin-dik-ene makes a shirt and a tubeteika for the child, and the parents pay for this with gifts.

rch. Bolshoy Kebin

When a boy is born, a woman comes and cuts the umbilical cord, washes the baby with salty water, and wraps him in rags.

The skin and chest of the slaughtered livestock are given by the father (of the child.— B.K., S.G.) to the kin-dik-ene (mother of the umbilical cord) — the woman who cut the umbilical cord.

Zhanyzak

solto

For the first two or three nights, the kin-dik-ene stays with the birthing woman to protect her from attacks by the albarsty-martui.

local. Sarybulak

Zhentek

buku

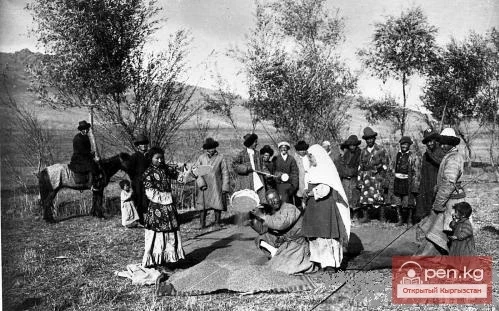

Zhentek13 is held on the day of birth, during which visitors give korumduk14.

Chonkur-Talas

kainazar

Zhentek — a custom of treating visitors who come to see the newborn child with oil stored in a sheep's stomach15 and with boiled dough. Guests must respond to the visit with a gift of korumduk.

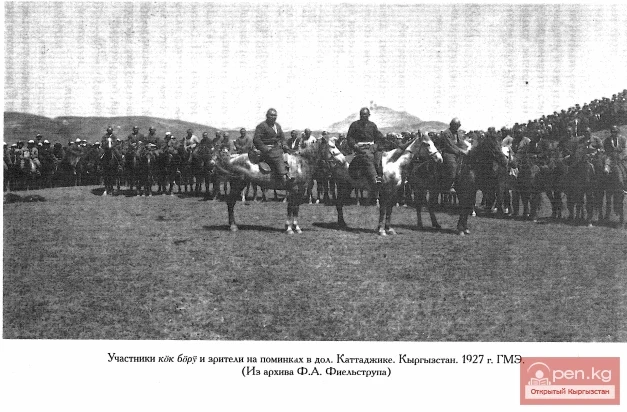

Upon the birth of a child, the father gives kok boru.

A celebration for the birth of a child varies in size depending on the parents' wealth. Neighbors are invited to it.

Zhanyzak

solto

Zhentek is made — visitors are treated (women come themselves, men are invited) with karynmaeli boorsak. The kin-dik-ene takes the child and shows him for korumduk (various small gifts). The closest friend of the birthing woman brings a shirt.

Bathing the child

Zhanyzak.

solto

After the child is born, he is washed in warm water. For 40 days, he is washed every two to three days in salty water16.

rch. Bolshoy Kebin

After 40 days, the birthing woman makes 40 flatbreads and distributes them to the gathered guests; they pour 41 spoons of water into a vessel, sprinkle salt into the water, and then bathe the child in this water.

local. Sarybulak

buku

The newborn is immediately bathed in salty water upon birth. This continues for 40 days. On the 20th or 40th day, a celebration is held. They take 40 spoons of clean warm water and wash the child with good city soap17.

At birth, the child is dressed in a collarless shirt, and after the fourth day — in a regular one with a collar18.

Later, the kin-dik-ene brings a shirt along with tokach, tea, and other food.

Woman's impurity

Pishpek District, Buraninskoye Village

For 40 days, a woman is considered impure, does not sleep with her husband, does not pray, but is not subject to special isolation19. After this period (which is not strictly observed), she washes, dresses cleanly, and performs prayers.

Kydyr

A woman is considered impure during menstruation; she does not cook during this time, does not pray, does not approach the cauldron, and does not sleep with her husband.

rch. Makmal

Sake

After childbirth, a woman is considered impure for 40 days only according to Sharia, not by custom.

rch. Bolshoy Kebin

For the first 40 days after childbirth, a woman does not sleep with her husband.

Placement in the cradle

rch. Bolshoy Kebin

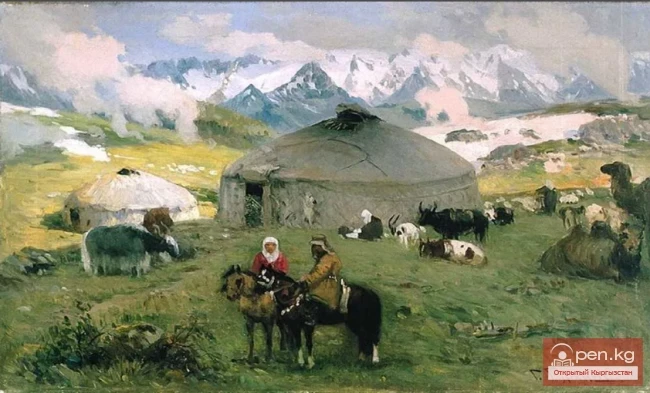

Before placing the child in the cradle, an old woman is presented with boorsak on a plate, five alchiks, and an axe. The old woman takes the axe and places it in the cradle so that the child is strong like the axe; she also places the alchiks so that he learns to play well20; she sprinkles some boorsak: whoever manages to take the boorsak from there eats it21. The remaining boorsaks are divided among the women and eaten. Then, after removing the axe and alchiks, the infant is placed in the beshik.

Zhanyzak

solto

The infant is placed in the cradle three days after birth. This is done by an old woman22 from the same village. This moment is accompanied by a celebration. In the cradle, bou23 is attached on one side, and the infant is wrapped without a blanket.

kainazar

The child is placed in the cradle on the third day, and a celebration is held. The cradle is placed by an old woman and she receives a gift for this.

"Kutty bayanu kylsyn" (May happiness be complete).

"Janin uzak bolsun" (May your life (soul) be long), says the old woman at this time. The child is showered with boorsak. An alchik is tied to the cradle's handle (for a boy? — F.F.).

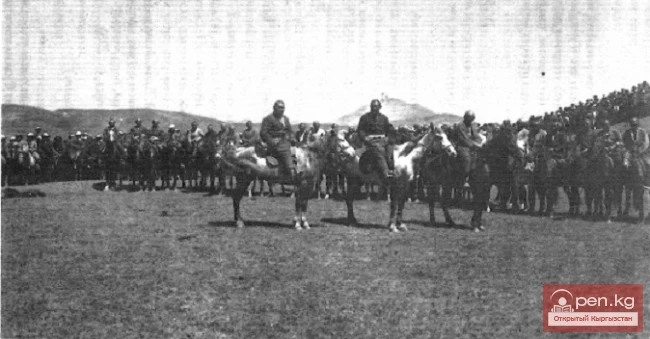

Ysyryk — around the hole for draining impurities, fire is drawn. When the child is placed, the old woman who placed him sits on the cradle three times, driving it with a whip, saying: "Janin uzak bolsun, janin Kudai goysin" ("May your life be long, may God preserve your soul!")24.

Pishpek District, Buraninskoye Village

sarybagysh

The child is placed in the cradle 40 days after birth. The men and women gathered for the celebration express their wishes.

Osh District.

Taveke

adigine

The child is placed in the cradle on the fourth or fifth day, and the cradle is brought by a relative.

local. Sarybulak

Alimbek

buku

The infant is placed in the cradle two to three days after birth. An old woman places him so that he lives to her age25. A celebration is held, a lamb is slaughtered, and guests of both sexes are invited. They also prepare zhambash-kuyruk26. The infant is placed in the beshik until the celebration.

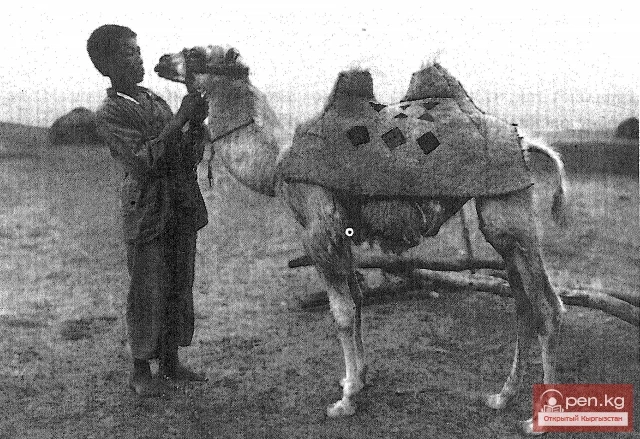

The old woman takes an axe, kerki, two alchiks (from the right and left foot) and places all this in the beshik, rocks it, then asks: "Ong by? Ot by?" Someone from the women answers: "Ong"27. While rocking, the items fall off, the axe is nudged to make it fall out. During this, they perform alasta28 with archi or another wood and, bowing, throw fat into the fire29.

Alasta is done daily over the cradle, if the mother does not forget (p. 74).

Comments:

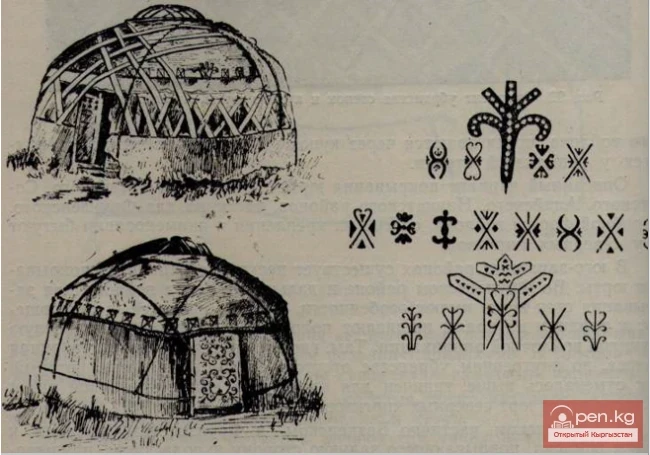

1 The post in the center of the yurt, the home — a sacred part of the dwelling. It symbolizes the "sacred tree," the "world tree," which is a symbol of life, well-being, helps to give birth and raise children, and has many other functions. (Frazer J. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. Moscow, 1980. pp. 129-141; Freidenberg O.L. Poetics of Plot and Genre. Leningrad, 1936. p. 72; Lvova E.L., Oktyabrskaya I.V., Stana aei A.M., Ushanova M.S. Traditional Worldview of the Turks of Southern Siberia: Space and Time. Material World. Novosibirsk, 1988 (Hereinafter: Traditional Worldview of the Turks... I). pp. 32, 58-60), Among the Tajiks, according to N.S. Babaeva's materials, the central post in the house embodies the tree in which the spirits of ancestors are embodied (Babaeva N.S. Davra — the ritual of redeeming the sins of the deceased // Ethnography of Tajikistan. Dushanbe, 1985. p. 61). It is not surprising that women of many peoples of the world held onto the post in the center of the dwelling during childbirth. See: Frazer J. Op. cit.; Lvova E.L., Oktyabrskaya I.V., Sagalaev A.M., Usmanova M.S. Traditional Worldview of the Turks of Southern Siberia. Man. Society. Novosibirsk, 1989. (Hereinafter: Traditional Worldview of the Turks... II). pp. 148-149; see also articles in the collection "Traditional Child-Rearing among the Peoples of Siberia" L., 1988). It is not by chance that birthing women offered sacrifices to the tree (or pole symbolizing it), for example, by anointing it with oil, as the Yakuts did (Novik E.S. Ritual and Folklore in Siberian Shamanism: A Comparative Structural Approach. Moscow, 1984. p. 165) and generally addressed it as a deity. The Altaians called the pole that the birthing woman held onto "Mother - birch," while the Khakass called it "altyn teek," i.e., "golden stick." By the way, among the Karachays, the "altyn tayak" was called the stick of the deity Chopp, who was the patron of fertility and was regarded as a demiurge, the creator of the life principle (Karaketov M.D. From the Traditional Ritual-Cult Life of the Karachays. Moscow, 1995. pp. 3, 80).

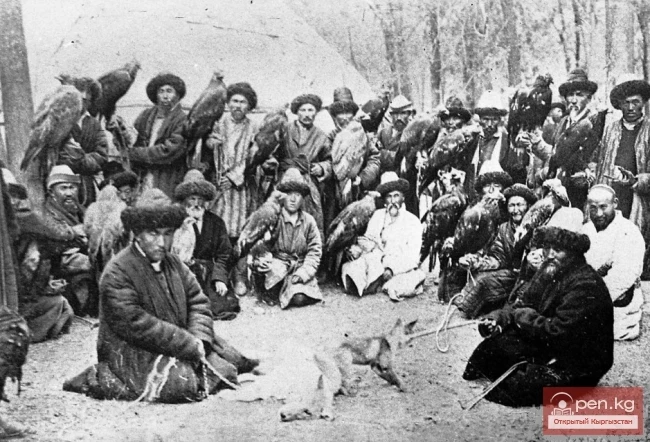

2 The Kyrgyz also have another way to help the afterbirth come out. Since difficulties are associated with the machinations of evil spirits, they bring an owl and make it cry, for evil spirits fear its voice (Simakov G.N. Falconry and the Cult of Birds of Prey in Central Asia. Ritual and Practical Aspects. St. Petersburg, 1998. p. 69).

3 Ton - one of the meanings of the word "afterbirth, child place" (Yudakhin K.K. Kyrgyz-Russian Dictionary. Moscow, 1965. p. 748). Interestingly, among the Tuvans, the afterbirth is called chop (D'yakonova V.N. Childhood in the Traditional Culture of Tuvans and Telengets // Traditional Child-Rearing among the Peoples of Siberia. L., 1988. p. 168). Compare with the name of the fertility patron among the Karachays, Chopp (see above).

4 Many peoples of the world considered the afterbirth (child place), like the umbilical cord, a living being, a brother or sister of the newborn, or an object in which the child's guardian spirit resides or part of its soul (Frazer J. Op. cit. p. 52). Among the ancient Turks, the afterbirth was also called umai. The goddess who was the protector of birthing women and infants was also called that (Ancient Turkic Dictionary. L., 1969. p. 611). One of the first works on the cult of Umai, the goddess of fertility among Turkic peoples, was N. Dyrenkova's article "Umai in the Cult of Turkish Tribes" (Culture and Writing of the East. Baku, 1928. Vol. III. See also: Potapov L.P. Umai — the Deity of the Ancient Turks in Light of Ethnographic Data // Turkological Collection, 1972. Moscow, 1973; Butanaev V.Ya. The Cult of the Goddess Umai among the Khakass // Ethnography of the Peoples of Siberia. Novosibirsk, 1964; Abramzon S.M. The Kyrgyz and Their Ethnogenetic and Historical-Cultural Connections. L., 1971. pp. 275-280, ch. "The Cult of Mother Umai." All works provide extensive literature on this issue). Since the placenta, like the umbilical cord, is in sympathetic connection with the child, its preservation depended on the child's health, life, and fate (Frazer J. Op. cit. p. 51). This is why many peoples, including the Kyrgyz, bury the placenta in a secluded place, sometimes in the house at the threshold, in a pile of ash at the hearth, or at the central post in the room (Frazer J. Op. cit. pp. 51-52; Potapov L.P.

Essays on the Everyday Life of Tuvans. Moscow, 1969. p. 267; Troitskaya A.L. The First Forty Days of the Child (chilly) among the Settled Population of Tashkent and the Chimbulak District // V.V. Bartold: Turkestan Friends, Students, and Admirers. Tashkent, 1927. p. 352; She also. Birth and Early Years of the Child of the Tajiks of the Zaravshan Valley. Based on the Materials of the Central Asian Expeditions of the USSR Academy of Sciences in 1926-1927 // SE. 1935. No. 6. p. 116; Abramzon S.M. Birth and Childhood of the Kyrgyz Child // Collection of the MAE. Moscow; Leningrad, 1949. Vol. XII. p. 101; Snesarev G.P. Relics of Pre-Islamic Beliefs and Rituals among Uzbeks of Khorezm. Moscow, 1969. p. 91; Kislyakov N.A. Family and Marriage among Tajiks. Based on Materials from the Late 19th to Early 20th Century. Moscow; Leningrad, 1959. p. 51; Esbergenov K., Atamuratov T. Traditions and Their Transformation in the Urban Life of Karakalpaks. Nukus, 1973. pp. 136-137; Butanaev V.Ya. Op. cit. pp. 211-212; Toleubaev A.T. Relics of Pre-Islamic Beliefs in the Family Rituals of the Kazakhs (19th — early 20th century). Almaty, 1991. p. 69). However, among some population groups, for example, among the Tajiks of Karatag, Falgara, and among the Kyrgyz, there was a belief that if a dog ate the afterbirth, the woman would have as many children as a dog has (Troitskaya A.L. Birth and Early Years... p. 116; Peshtereva E.M. Wedding in the Artisan Circles of Karatag // Family and Family Rituals among the Peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan. Moscow, 1978. p. 62). The Khorezm Uzbeks only threw the afterbirth to a dog if children in the family did not survive (Snesarev T.P. Relics... p. 93).

B.A. Litvinsky relates the custom of burying the afterbirth in the house or near the house to the widely spread ancient practice of burials under the floors, walls, or doors of dwellings. Thus, writes B.A. Litvinsky, the idea of fertility, well-being of the living is manifested, as well as the connection of burial with the dwelling, particularly with the hearth (burying in ash) (Litvinsky B.A. On the Antiquity of One Central Asian Custom // KSIÉ. 1958. Vol. XXX. pp. 32-33).

According to the beliefs of the Karachays, the afterbirth is a muddy shell from which the child emerged, and burying it by the river or even throwing it into the river frees the family from misfortunes stemming from the afterbirth, as Mother Water (Suu-Anasy) takes both the spirit of the afterbirth and the misfortunes associated with it into the sea abyss (Karaketov M.D. Op. cit. p. 110, 114).

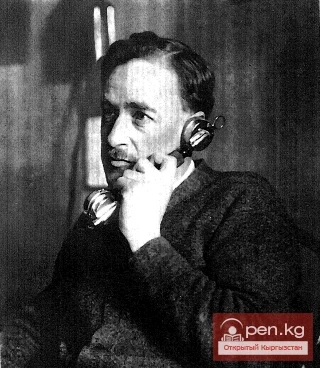

5 The midwife played an important role in childbirth among almost all peoples of the world, as her skill often determined the life and health of the birthing woman and the infant. She was entrusted with the important task of cutting the umbilical cord that connects the child to the mother. Therefore, the midwife should be a good, kind person. Among the Turks, there is a belief: whoever cuts the umbilical cord, the child will resemble them (Serebryakova M.N. Traditional Institutions of Child Socialization among Rural Turks // Ethnography of Childhood: Traditional Forms of Child and Adolescent Education among the Peoples of the Near and South Asia. Moscow, 1983. p. 42). Tajik women of the Yagnob region even tried to cut the umbilical cord themselves, as they considered it a sin to pass this task to someone else (Peshtereva E.M. Op. cit. p. 61). According to the beliefs of the Turks, the midwife embodies the "earthly double" of Mother Umai (see: Traditional Worldview of the Turks. II. p. 152), the protector of birthing women and infants, who is invisibly present during childbirth, helps the infant to be born, and then protects him until the age of three. It is the midwife among the Karategin Kyrgyz who spends 2-3 nights with the birthing woman to protect her from attacks by the albarsty (a demonic creature in the form of an old woman that harms the birthing woman; the antithesis of Mother Umai), embodying the goddess Umai (Karmysheva B.H. Personal Archive). It is she who among the Karategin Kyrgyz is given a bowl of flour and a piece of salt (products that have sacred significance), which are held over the birthing woman's head, with the words "Umai enaning hakiga," i.e., "In the share of Mother Umai." It is to the midwife that the northern Kyrgyz, according to F.A. Fielstrup's records (see below), give the skin and chest part (remember that the skin is one of the sacred parts of the animal, and the chest part is one of the most prestigious parts) of the livestock slaughtered in honor of the child's birth. The fire in the home hearth was also called Umai-ene.

6 As mentioned earlier, the umbilical cord is in sympathetic connection with the child (see note 4), and its preservation depends not only on health but also on the child's fate. Therefore, some peoples hung the umbilical cord on a tree if a boy was born, so he would become a good hunter, buried it under the mortar or at the hearth if a girl was born, so she would be a good housekeeper (Frazer J. Op. cit. pp. 51-52), or simply kept it in the house to ensure the child's safety (Frazer J.; Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. p. 72; Butanaev V.Ya. Op. cit. p. 211). The Tuvans, Khakass, Karakalpaks, and other peoples hung the dried umbilical cord on the child's cradle as a protective charm (Potapov L.P. Essays... p. 267; Butanaev V.Ya. Op. cit. p. 211; Esbergenov K., Atamuratov T. Op. cit. p. 145; Chvyr' L.L. An Attempt to Analyze One Modern Ritual in Light of Ancient Eastern Concepts // Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Foreign East in Antiquity. Moscow, 1983. p. 125). In Matche, a piece of the umbilical cord was sewn into the mother's shirt to prevent evil and ensure future easy childbirth (Troitskaya A.L. Birth and Early Years... p. 116). And all this is not accidental. After all, the umbilical cord was one of the symbols (along with a bow and arrow, a cowrie shell, a bronze button, sheep astragali, a spindle) of Mother Umai.

7 Kuuchu — literally, "chaser." A healer, supposedly capable of driving away evil spirits from the birthing woman (Yudakhin K.K. Op. cit. p. 456).

8 About albarsty (albastry) see: Litvinsky B.A. The Semantics of Ancient Beliefs and Rituals among the Pamiris // Central Asia and Its Neighbors in Antiquity and the Middle Ages (History and Culture). Moscow, 1981. pp. 101-104. The literature on the subject is also provided there.

9 A Muslim custom. Upon the birth of a child, it is primarily customary to pronounce the azan (call to prayer) in his right ear. A man does this. This act protects the child from the machinations of jinn.

10 Kalzha — literally, "well-cooked meat" (Yudakhin K.K. Op. cit. p. 331). Among the Kazakhs, the meat of kalzha must be tasted first by the birthing woman; otherwise, she might have postpartum contractions (Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. p. 74).

11 Kin-dik-ene — literally, "mother of the umbilical cord." This is what the midwife who cut and tied the umbilical cord was called (see note 5). It seems that the name Kin-dik-ene was synonymous with Umai-ene.

12 See note 5.

13 Zhentek — a feast held on the occasion of the birth of a child. It is usually held on the day of birth. However, if the child is temporarily given to another house (see the section "In Families Where Children Do Not Survive"), then zhentek is held in the adoptive house.

14 Korumduk — gifts brought by those who come to see the child.

15 Karynmay — from karyn — the stomach of a sheep or goat, used as a vessel for storing oil, may — oil, i.e., butter stored in the stomach of a sheep or goat. For details on the use of stomachs as vessels, see: Gubaeva S.S. The Population of the Fergana Valley in the Late 19th to Early 20th Century. Ethnocultural Processes. Tashkent, 1991. p. 42.

16 Salt during bathing apparently played both a profane and a sacred role. It was used to rid the child of bites from flies, mosquitoes, rashes, and generally to make the child stronger (Gershenovich R.S. On the Domestic Hygiene of Uzbek Infants // Proceedings of SAGS. Series XXN-b. Ethnography. Tashkent, 1928. Issue 1. p. 4; Troitskaya A.L. The First Forty Days of the Child... p. 352; Abramzon S.M. Birth and Childhood of the Kyrgyz Child... p. 101). But salt was also supposed to symbolize happiness, health, and prosperity (Troitskaya A.L. Birth and Early Years... p. 120; Chvyr' L.A. An Attempt to Analyze... p. 125).

17 In the years when F.A. Fielstrup collected his material, the Kyrgyz bathed the child immediately after birth or a few days later. The Karategin Kyrgyz, judging by B.H. Karmysheva's records, bathed the infant for the first time on the third day after birth, and the second time — only on the 40th day in 40 spoons of water. The Tajiks of Karatag bathed the infant three days later if he was born clean, and on the same day if he was born dirty (Peshtereva E.M. Op. cit. p. 63), the Tajiks of Rushan and Shahristan bathed only on the 20th day, while the Tajiks of Samarkand — even on the 40th (Kislyakov N.A. Family and Marriage... p. 57). A special ritual dedicated to the first bathing of the child was observed among the Khorezm Uzbeks (Snesarev T.P. Relics... p. 92) and among other peoples of the Turkic-Mongolian world (Traditional Worldview of the Turks. I. p. 160) and not only among them. For example, the Aysors (Syrians) on the seventh day of the child's life take him out of the "sevens": they undress him with the participation of the midwife and, in the name of the Lord, pour 7 spoons of water over his head, corresponding to the number of days lived.

The same is repeated on the 40th day (Muratkhan V.P. Customs Related to the Birth and Upbringing of Children among the Syrians of the USSR: Based on the Materials of the 1928-1929 Expedition to the Syrians of the Armenian SSR // SE. 1937. No. 4. p. 71).

All this data suggests that bathing the newborn was not so much a cleansing act as a ritual one. The appearance of the child was, in essence, a rejection from the world of nature and "an initiation into the world of people" (Traditional Worldview of the Turks... I. p. 159). Bathing, i.e., turning to the water element, in which he was in the mother's womb, as it were, returned the child for some time to the nature that birthed him (Ibid. p. 160) in order to perhaps ease his transition to the world of people. It seems that the first bathing thus had an initiatory character: the child transitioned to a new stage, to a new incarnation for himself, into the world of people. It is not by chance that on this day, i.e., on the 40th day, the Kyrgyz in several regions (see below) shaved the birth hair, which again was from a different state of the child.

Interestingly, according to the Tajiks of the Khuf Valley, it is precisely after 40 days that the "animal spirit," which until then constituted the child's soul, gives way to the "human soul" (Andreev M.S. Tajiks of the Khuf Valley (Upper Amu Darya). Stalinhabad, 1953. Vol. I. p. 71).

It should be noted that in the entire ritual, as well as in family rituals in general, the number 40 is not accidental. According to the authors of the book "Traditional Worldview of the Turks of Southern Siberia," the number 40 is a "quantitative-qualitative indicator of the state of transition" (Traditional Worldview of the Turks... I. p. 162). It is precisely after 40 days that the birthing woman transitions from a state of sacred "impurity" to her normal state; after 40 days, the newborn and his mother become less vulnerable; after 40 days, the soul of the deceased finally breaks from this world and flies to another world; after 40 days, the newborn transitions from the world of nature to the world of people, etc.

18 The first shirt put on the newborn was called "it koynek," i.e., "dog's shirt" among many Turkic (and not only Turkic) peoples. Sometimes it was first put on a dog to deceive evil spirits or to transfer all misfortunes intended for the child onto the dog (Troitskaya A.L. Birth and Early Years... p. 116; Abramzon S.M. Birth and Childhood... p. 101; Kislyakov I.L. Family and Marriage... p. 51; Esbergenov K., Atamuratov T. Op. cit. p. 149; Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. p. 75; Chvyr' L.A. An Attempt to Analyze... p. 126; She also. Three "chillas" among the Tajiks // Ethnography of Tajikistan. Dushanbe, 1985. p. 71). But it seems that the "dog's shirt" also indicated that the infant still, until a certain period (most often), belongs to the "animal" world. The regular shirt was only put on after the ritual bathing (see above).

19 The taboo regarding women during menstruation and childbirth was known to many peoples of the world, when they were not allowed to touch things, food, or people for a certain period. The birthing woman was especially considered impure, and efforts were made to isolate her from society during childbirth by placing her in specially constructed huts. All those who touched the birthing woman and the newborn during the forbidden period were also considered impure (Frazer J. Op. cit. pp. 237-238). However, according to the beliefs of the Khakass, a pregnant woman is like a river during a flood, and entering the dwelling of a pregnant woman was as dangerous as entering a full river (Traditional Worldview of the Turks... I. p. 19). It is quite possible that the taboo on birthing women, as well as on pregnant women, was explained not only by the sacred impurity of the woman but also by the possibility of death or misfortune for those who came into contact with them.

20 Alchiks (astragals) played a significant role in Turkic rituals related to child-rearing. An alchik is not just a playing die placed in the cradle so that the boy will play well in the future; moreover, alchiks are also placed in the cradle of a girl; it is also not just a magical means for strengthening the skeleton, for which many Turkic peoples allegedly tied a bundle of alchiks to the cradle (Traditional Worldview of the Turks... I. p. 60). An alchik is primarily, it seems, a protective charm. Remember that one of the symbols of Mother Umai was alchiks. Therefore, they are placed in the cradle or tied to it so that Mother Umai herself protects the infant.

21 Boorsak is sprinkled in the cradle so that the newborn's life will be abundant, and the women hurry to eat them so that, as G.P. Snesarev writes, they too may await such an event (Snesarev T.P. Relics... p. 101), and generally, so that they too may receive blessings.

22 The infant is placed in the cradle by an old woman so that he may live as long as she does. Among the Tajiks of the Khuf Valley, for example, a boy aged 6-10 places the child, but it is essential that his parents are alive (the latter condition is necessary for the newborn's parents to also live long). The boy says at this time: "Become an old man (old woman), reach deep old age" (Andreev M.S. Tajiks of the Khuf Valley. p. 68).

23 Bou — a rope, a tie; in this case, ties for securing the infant in the cradle.

24 The old woman sits on the cradle, imitating a rider; she even drives the cradle with a whip (kamchoy). If the old woman is the rider, then the infant on whom she "sits" is the horse. And evil spirits, as is known, feared horses and everything associated with them, especially whips. A similar ritual is noted among the Kazakhs (Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. p. 72). Among the Karategin Tajiks, in families where children died, the newborn was passed under a horse (camel, donkey, wolf skin, etc.). In this case, evil spirits took the child for a horse (camel, donkey, wolf, etc.) and left him alone (Tajiks of Karategin and Darwaza. Dushanbe, 1976. Vol. III. p. 78). See note 22.

25 The old woman is a particularly honored guest, and she is given tasty pieces of meat.

26 Zhambash — the ilium bone with meat served to an honored guest; kuyruq — tail, fat tail, also served to honored guests.

27 Ot by? — "Is it correct?" Ot — "Correct."

28 Alasta — to fumigate with archi (a healing method) to drive away evil spirits (Yudakhin K.K. Op. cit. p. 46).

29 Fat is thrown into the fire, i.e., a sacrifice is made to the hearth (see note 43 in the section "Wedding Rituals"), as well as to Mother Umai. As mentioned earlier, fire was also called Mother Umai.

Summary of the marriage ritual made by F.A. Fielstrup himself. From the ritual life of the Kyrgyz in the early 20th century. Part - 9