The First Wedding Night

Zhanyzak

solto

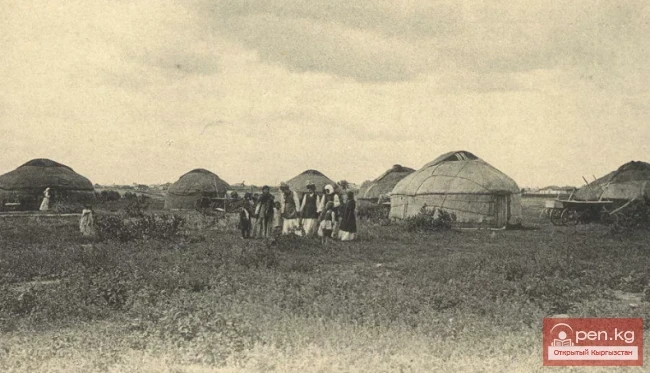

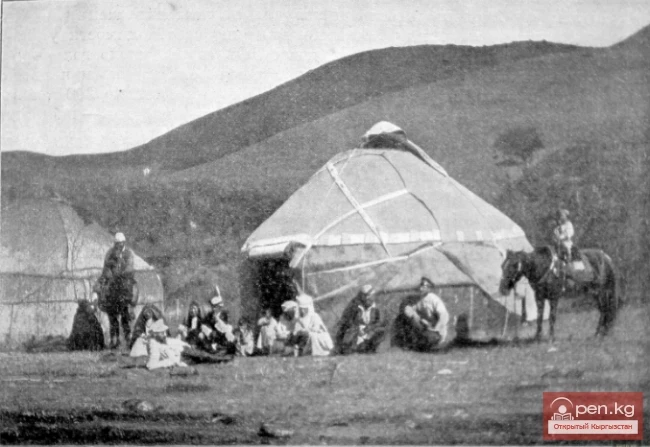

By the evening before the departure, all the dowry is packed into the orgё. Soft items, nine pieces of each kind, are stacked, and the bride is awaited by the groom. From the father's yurt, a young woman is brought to the groom on a white felt42. He accepts her, and they sleep on this soft bed.

Before the groom enters the orgё, the bride's father slaughters a ram, prepares the meat there, and throws the raw head of the ram out through the smoke hole. This head does not return to the yurt; someone catches it and takes it away43. Everyone, including the groom and bride, is treated to food. After the feast, before sleeping, the groom and bride stand behind the yurt. They are draped in some old clothes so that the good ones do not get spoiled. A ram or a kid is slaughtered44, the lungs are taken out and used to hit the heads of the young couple. This is called sadaqa. The lungs are then thrown to the dogs, and the kid (lamb) is given to a poor person45. After that (after the kız ойун46), all the guests are treated to meat and go home. In the orgё remain the groom with a friend and the bride with the jenge. The jenge lays out the bed, and the young couple lies down to sleep. The jenge and the groom's friend leave. After half an hour, the jenge approaches the yurt and asks if everything is well. If the answer is affirmative, the jenge receives a foal (tai) brought by the groom. In the morning, the young wife brings her husband trousers, a shirt, a cap, and to his friend — a belt, and they both go home.

After the first night, the groom's father, through another person, inquires whether the bride pleased his son. Learning that his son is taking her, the father, along with two friends, brings a horse as a gift and goes to the bride's father. He also invites two people — and they negotiate the kalym.

r., Makmal-Naryn near Toguz-toro

Jingish aji

During the first night visit (lying down) of the groom with the bride, aunts watch over them, and in the morning, while collecting the bed, they inspect it. If the groom has exercised his rights earlier, then after the nikah, after the legal wedding night, there will be no questions or bed inspection; if not, they observe every subsequent night spent together until results are achieved. If there are no results even after the nikah, the groom is asked whether he is satisfied. The bride could have lost her innocence not due to the groom but before him. All this does not apply to a minor groom.

Karakoл

On the night after the wedding, two women watch the behavior of the young couple and ask the groom about the situation; they are placed in the same yurt.

No one prevents him from going to bed.

Talas

Cholponkulov

kainazar

After the party (after the kız ойун and the last toya before the young couple's departure. — B.G., S.G.), the young couple is put to sleep in the orgё. Gifts follow for the bed — toshёk salar. At night, outside, the jenges sit, asking the young man if the bride is honest, and report news to her parents, who give them a gift.

On the same day, the parents slaughter a horse and bring it to the bride's parents.

Attitude Towards the Bride's Chastity

r. Tyup

Jingish aji

The question of the bride's chastity was asked less frequently when the marriage was a matter settled between the parents, and the groom and bride had been engaged since childhood.

Jingish aji

Oiyip — what the bride's father pays if she is not chaste. They check in the morning on the white coverlet on which the young couple slept. The groom can refuse the wife in case of her guilt. If the aunt (jenge) knows about their premarital connection, she can inform her parents, and then the young man can no longer refuse his wife,

r. Tyup

Jingish aji

The question is not about the bride's virginity but about whether the groom is satisfied.

r. Bolshoy Kebin

Sagimbay

All the dowry is packed into one yurt, newly set up by the groom's father (? — F.F.)47, and there the bed is laid.

The dowry can be piled up to the top of the yurt, and therefore the bed ends up being high up. The bride is seated there. The groom comes into the yurt, extends his hand to her to help him climb up. If she loves him deeply, she will help him immediately; if not, she will only pull him halfway the first time, and then let go, causing him to fall.

When he climbs up the second time, they lie down to sleep on the white blanket covering the bed. While they are lying down, the young men and women shout to them: "Faster! Faster!" If the groom responds: "Yes!", it means the bride is a girl; otherwise, he says: "No!" If the young woman was chaste, the women climb up, pull the blanket off, and take it to show her parents. In joy, they give them gifts. If the answer was "no!", everyone disperses silently — a disgrace for her father and mother. For the dishonesty of the bride, the son-in-law is given a camel or a horse.

The Wedding Game of the Youth — kız ойун48

r. Bolshoy Kebin

Zhanteli

Everyone goes to the wedding. They bring livestock, slaughter a ram, and transport it raw, cooking it in the bride's aul and treating the locals there.

In turn, the hosts treat the guests with their food. The next morning, the bride's father states how much kalym he requires. Both sides bargain (hunting dogs, golden eagles, runners, etc. are taken into account; previous gifts are not counted). From the moment of the agreement, preparations for the bride begin, clothing and dowry are prepared, while the guests live here for 15 days to 1 month.

During this time, the groom lives in the orgё with the bride. The entire orgё with its contents, pack camels, and a gaited horse for the bride is provided by her father. The dowry is given without negotiation, on trust. During this period, the kız ойун takes place.

Sagimbay

When the groom arrives for the second time, 7-10 days before the arrival of the parents to take the bride to his aul, the youth arrange a kız ойун (evening party).

When the groom arrives, he sends women to the bride's mother to ask for permission to go to the evening party; the women say: "We came at your son-in-law's request."

In the yurt, the groom and bride sit next to each other in the middle, while others sit around. They start to play. They make a rope from a scarf. In the middle of the yurt stands a young man with the rope in his hands and sings a ыр (song), in which, without naming names, he describes the beauty of the girl, for example, and throws the rope to one of the attendees. She grabs the rope and begins to whip the young man, after which they both kiss: standing back to back, they half-turn, embracing each other over the shoulder, while the young man does not fail to squeeze his partner's breasts; and so first on one side, then on the other (the girls sing).

Then the girl takes the place of the young man and hits someone else from the young men, and they kiss, and so on. The groom and bride do not actively participate in the game but only perform once: in the middle stand a young man and a girl and ask them on behalf of the present girls to kруттремыс — so that the groom and bride get acquainted (? — F.F.)49. The young man approaches the groom, the girl approaches the bride, they take them by the hands, lead them to the center of the yurt, and make them kiss (see above), they also kiss, and then all the attendees kiss in this way. And so until morning.

Karakoл District, Valley of the River Tyup

Two to three months after the conclusion of the agreement (principle) between the fathers, the groom, taking with him a runner, three mares, and one tai, goes with a friend to the aul of the bride's father. They arrive there in the evening. A few days before this, he sent a person to inform the bride's parents that he would arrive on such and such a day. By this day, a separate yurt (orgё) is prepared. When he is seen from the aul, the bride's parents leave the yurt. The matchmakers (aunts) receive the groom. He approaches the orgё and enters. In the aul, a ram is slaughtered, and the groom and his friend are treated. Then the girls, young women, and young men are gathered, and an oyun is arranged. The bride is called to the party by a close woman. The groom and bride sit and do not participate in the games. He sits to the right of his bride. The game is started by a young woman-organizer, a relative of the bride. The girls sit at the upper part of the yurt, the young men at the lower part.

The organizer takes a tokmok (rope) and gives it to a girl, who goes and hits a young man with it, who in response sings a song, then stands up; the girl who called him to sing also stands up, and they kiss, standing back to back (see above), and so on. Only once does the groom's friend sing — when the organizer hits him and demands that the groom and bride kiss — he sings for the groom. Thus, the oyun continues until midnight.

Talas

Cholponkulov

kainazar

For the last feast, a day is chosen (excluding unlucky Tuesday, Friday, and Saturday50). A party is appointed, to which the entire district gathers, at someone's place, and the father of the groom pays the host of this yurt for the treats. There, the bride receives a gift called kız ойнатмок51. At this party, the parents of both sides and older people do not attend.

The youth play: women, girls with men (2 groups). The organizers are representatives of both groups. The groom and his friend are in the circle of women but do not participate in the games, remaining spectators.

One of the games is a kissing game. Two bies are chosen from each side, one or the other sits closer to that and the other side. Besides them, there are also those who lead the participants into the arena (performers — bashny52). When returning from the party, the parents of the groom sit at the father-in-law's place, and at the threshold inside his yurt, a new silk scarf is spread out.

Entering the yurt, the young couple bows to the parents; whoever steps first on the scarf upon entering will be the head of the family. The bride stays with her father, while the groom immediately goes to the orgё. The jenge arranges the bed in the orgё, the groom lies down, and the bride is brought to him after her parents have gone to sleep. Early in the morning, the bride returns to her father's yurt.

Comments:

42 The felt is usually made from sheep wool. Everything related to the ram is sacred, especially the wool. Among the Karachays, not the entire kid (the goat is also a sacrificial animal) is sacred, but only the skin, tail, and the first three vertebrae in the tail (Karaketov M.D. From the Traditional Ritual and Cult Life of the Karachays. Moscow, 1995. P. 83). Furthermore, the ram's skin (like the skin of other totemic animals) is considered a symbol of fertility, according to researchers.

It is not surprising that among many peoples, the bride was seated on the skin of an animal, laid with the wool side up (Lobacheva N.P. Wedding Ritual... P. 43; Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. P. 29-30). Among the Khorezm Uzbeks, the bride was initially lowered onto a man's sheepskin coat when taken off the wedding cart (Lobacheva N.P. Wedding Ritual... P. 43).

Among the Uzbeks of the Kungrad tribe, according to the records of B.H. Karmysheva in the Kashkadarya and Surkhandarya regions, a carpet made of dyed sheep skins (khasali pustak) served as the upper covering for the newlyweds on their first wedding night, which they covered over the blanket (see also: Myths of the Peoples of the World. Moscow, 1982. Vol. 1. P. 238). A.T. Toleubaev suggests that carrying the bride on a white felt is connected with the custom of honoring newlyweds, who among many peoples were called by royal names ("prince, princess" — among the Russians, "sha" i.e. "king" — among the Tajiks, etc.), the chosen khan was also lifted on a white felt. And spirits fear royal figures and do not dare to approach the newlyweds (Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. P. 20-21).

43 As is known, the hearth and the smoke hole occupied a significant place in magical rituals. Apparently, because they were the receptacles of fire — the protector of man and family (see below). The Kazakhs threw the gnawed neck bone of a sacrificial ram through the smoke hole in the yurt of the newlyweds to ensure good smoke exit from the yurt (Kislyakov N.A. Essays... P. 109; Lobacheva N.P. Various Ritual Complexes... P. 304, 330; Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. P. 24). This, as is known, contributes to the non-extinction of the hearth. Among the Tuvans, the bride, having entered her father-in-law's yurt for the first time, pours milk, throws fat into the fire, and splashes milk into the smoke hole (Potapov L.P. Essays... P. 242), i.e., she makes a sacrifice not only to the hearth but also to the smoke hole. Among the Kyrgyz, according to F.A. Fielstrup, in the yurt of the newlyweds, the head of a sacrificial ram was thrown out through the chimney, which, according to reports from some informants, is later cooked and eaten, while according to others, this head does not return to the yurt, and someone catches it and takes it away. It seems that the latter is more accurate. After all, the head of the ram (as part of the whole ram) is a sacrifice to the chimney, which it must accept.

In Khorezm, a bow and pepper were hung at the chimney in the room of the newlyweds to protect the newlyweds from misfortunes (Snesarev T.P. Relicts... P. 85).

44 The kid, like the ram, was apparently a sacrificial animal to the sun and fire (the hearth). It bestowed fertility. Among Mongolic-speaking peoples, childless families sometimes kept a goat dedicated to the fire deity (Galdanova G.R. The Cult of Fire among Mongolic-speaking Peoples and Its Reflection in Lamaism // SE. 1980. No. 3. P. 100).

45 Kislyakov N.A. notes that among the Chuy Kyrgyz, before the first wedding night, a kid was slaughtered, and one of the women hit the young couple with its lungs and liver, seating them back to back and covering them with a robe. A similar ritual was recorded by N. Korzhenevsky among the Alai Kyrgyz (Kislyakov N.A. Essays... P. 120). Karmysheva B.H. recorded this ritual among the Karategin Kyrgyz (Karmysheva B.H. Personal Archive). This is done to protect the young couple from misfortunes and ensure their fertility. Apparently, this custom is connected with the general cult of the goat, which bestowed fertility (see note 44). Interestingly, the lungs were later thrown to the dog.

By the way, the afterbirth was also thrown to the dogs so that the woman would have as many children later as there are puppies in the litter.

Sadaqa (sadaга) — a redemptive or thank-offering, as well as a protection against the evil eye, as in this case. Usually, a kid is slaughtered for this. The kid is not eaten by them but given to a poor person, as it is a sacrifice.

46 It is possible that after такыя сайды, and not кыз оюн?

47 The wedding yurt was usually set up by the bride's father, not the groom's. It is not surprising that F.A. Fielstrup placed a question mark here.

48 See note 31.

49 Kız круштремыс — perhaps икыз куриштирмокп, i.e. "to introduce" to the girl (bride)?

50 Among the Tajiks of Karatag, wedding days are Thursday, Saturday (Peshtereva E.M. Op. cit. P. 182); among the Karategin Tajiks, "unlucky" times for closeness between the newlyweds were considered the night before Saturday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, while wedding days were Monday and Thursday (Tajiks of Karategin and Darwaz. Part III. P. 38, 53); among the Karategin Kyrgyz, weddings are not held in the month of Safar, and also on Tuesday, while weddings can be held in the month of Ramadan (Karmysheva B.H. Personal Archive); among the Karakalpaks, Wednesday was considered a "lucky" day for weddings (Esbergenov X., Atamuratov T. Op. cit. P. 83); among the Kazakhs — Wednesday, Thursday (Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. P. 15). Toleubaev A.T. writes: "According to the law of initial magic, this day was only the beginning of the desired action, and the appearance of the expected result was represented by the magical power of the 'lucky day'" (Ibid).

51 Kız ойнатмок — literally, "to entertain the girl".

52 Bashny — the leader, head, chief, commander (Yudakhin K.K. Op. cit. P. 121). So it would be more accurate to translate this word as "the one leading" rather than "performer".

Premarital Relations of the Young. From the Ritual Life of the Kyrgyz in the Early 20th Century. Part -3