Death — The First Day

Osh District

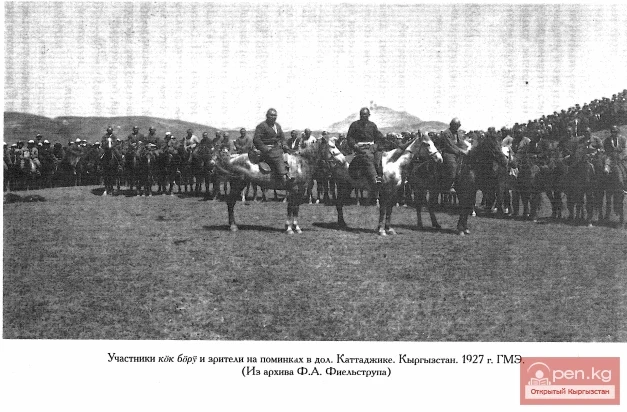

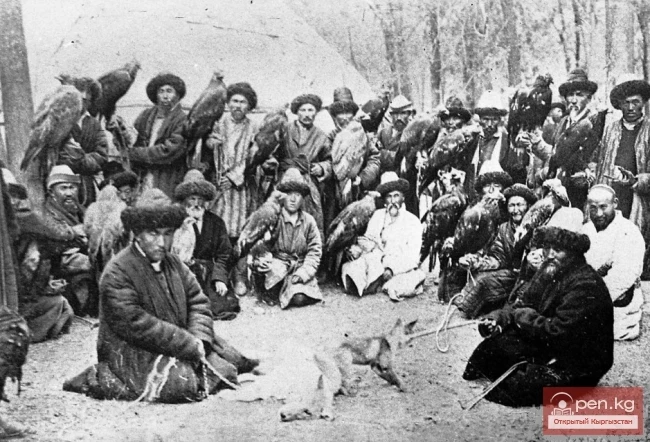

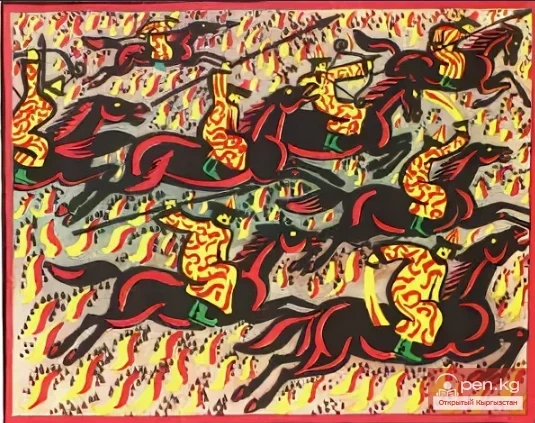

Gorbata — horse races held on the same day as the funeral.

At funerals, a baygu is organized, but not kok boru30.

Memorial wailing (koshok) and others.

Frunze Canton

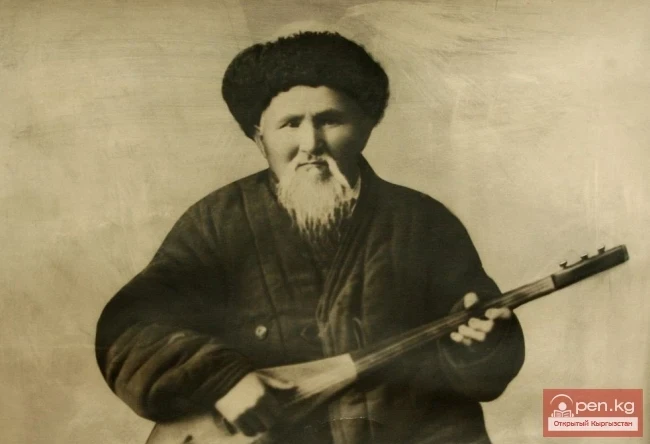

Koshok — a song-wail by women for the deceased, in which they remember him daily in the mornings (for the respected deceased) and in the evenings for a year.

Naryn

Koshok — women's wailing, lamentations; okuruk — mournful exclamations by men. They sing and shout while standing in a half-bent position, behind the yurt (opposite the place where the body lies in the yurt? — F.F.), when they arrive... This wailing begins from the moment the body is placed behind the koshok and continues all the time, without interruption, until the funeral; men — outside the yurt, women — inside.

Frunze Canton, Tokuzbulak

In the morning, at noon, and in the evening during the same period, the widow sings koshok together with close female relatives (by blood, marriage). Koshok is also sung during migrations: upon departure, passing through a foreign aul, at stops, and approaching the new campsite.

buku

Women during migrations and at stops wail (lament) when there is someone to see and hear them.

Kokomeran

sajak

Approaching the yurt of the deceased, about 100 sazhens away, those who have come to pay their respects begin to shout okuruk, and women, responding, sing koshok. Special mourners begin to wail when they hear that someone else has arrived; women in the yurt echo them.

The widow, sitting at home, sings koshok in the morning and evening — until asha. The last time women sing koshok is during asha, in the morning on the day of the marriage.

Osh District

Women sing koshok while braiding hair (on the third day)31. The widow continues to sing koshok until the nikah.

In general, the relatives of the deceased sing only in his yurt. For the first two months, the widow wails in the morning, at noon, and in the evening, and then only in the mornings. On the way (during migration), she always sings her koshok.

Men's Mourning

Osh District

Heirs do not shave their heads for 40 days (father, brothers, sons), but continue to wash.

However, they do not remove jewelry.

Mourning Procedure for Widows

The wives of the deceased gather in a neighboring yurt and sing with various lamentations; the wives of the deceased are assisted by women who have come with children.

As a sign of special grief, widows scratch their cheeks until they bleed, which is done very skillfully and without the slightest pity for themselves... Not to scratch the cheeks is not allowed, as they will be reproached, or even beaten. Scratched cheeks are considered good form until the last tribute to the deceased is paid, i.e., until asha, which occurs for wealthy people after a year.

During all this time (until asha), wives must observe complete chastity and, in addition, must begin and end the day with wailing and lamentation, for which they always have hunters to help. This wailing has a characteristic melody, so that upon hearing it, one always knows where the widow lives.

The Widow in the Yurt

Throughout the period from the moment of death until asha, the widow (widows) of the deceased sits in the presence of outsiders, turned away from them into the depths of the yurt, or behind the koshok (curtain); she does not turn away from those from the same aul33. During this same period, she (they) are not allowed to enter the black yurt.

buku

A young woman — the widow (of him? — F.F.) sat to the left (of the tor'a), turning away in our presence.

Kokomeran

sajak

The widow sits at home, does not enter other yurts, and sings in the morning and evening until asha. After the fortieth day, besides the widow, other women are allowed to visit other yurts.

Osh District

The widow does not perform any work until asha and only leaves the yurt when necessary. Relatives work for her.

kainazar

After kyrkash, the widow is no longer kept so strictly confined. Among the wealthy, mourning lasts a year, even if asha was performed earlier. Usually, however, after asha, if mourning continues, it is more in behavior than in appearance. In former times, the widow sat for a whole year at the tula, showing herself only to relatives.

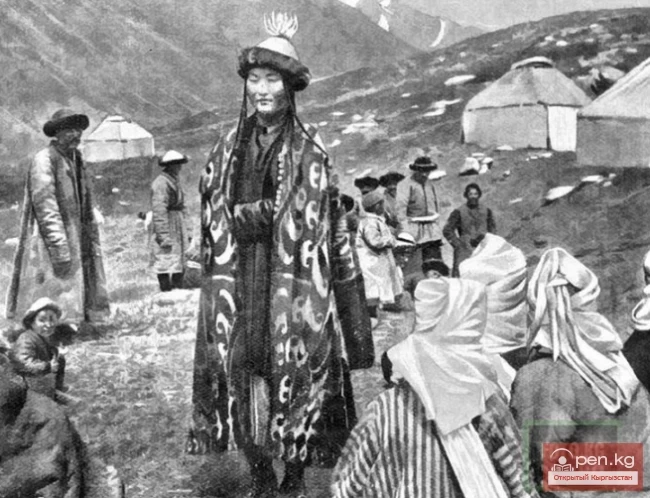

Mourning Attire of the Widow and Other Women

Karako

buku

The widow did not wear an elechek. After three to four years, she would wear a small low elechek, but before that, she only wore a zholuk35.

kydyr

Now the widow continues to wear an elechek (and over it a zholuk? - F.F.).

Naryn

ardakty

The widow wears a brocade beshmet with a white zholuk thrown over the elechek, covering her head and shoulders. The zholuk on top of the elechek is held with a strip of the same brocade (stoff? — F.F.) — kyrkak om.

Songköl

The mourning attire of the widow after asha is given to a poor woman, buku.

The mourning garment of the widow is without an elechek. Mourning is worn until asha, and after that, the clothing is usually given to a poor woman, rarely burned.

Kokomeran

sajak

Kara gidi — mourning of the widow: she covers her head with a blue or white scarf so that it falls slightly over her face. It is not tucked into her clothing, so it hangs on her shoulders. Across the forehead, for example, it is tied with a black ribbon.

Osh District

The widow wears a black koynok, chapán, zholuk. She does not wear a keptakhya and throws a black zholuk (scarf) over her head instead. Her hair is loose (until the third day). The widow wears mourning clothes until she remarries and removes them during the nikah. Or mourning is worn by the widow, mother, sisters, daughters until this clothing wears out.

Thus, mourning is usually worn by them for no more than a month. However, it can be extended by purchasing new mourning clothes. After removing mourning, they put on regular clothing.

A daughter also wears mourning for her father in her aul, if she is married, she does not let her hair down36. She wears an elechek, but without a keptakhya, and ties it with a strip of black fabric (her hair is covered with oromal).

kainazar

The widow wears a dark shirt, and instead of an elechek — a blue or black scarf. When the mourning is lifted, the widow's scarf is burned in the fire of the kerege just like the tuu. The elechek is brought by either the widow's mother or close relatives of the husband.

Ak zhalkasyn — the change from permanent black mourning to temporary (i.e., when mourning is worn only on certain occasions).

Mourning is observed for a year among the wealthy, even if asha was performed earlier. Usually, however, after asha, if mourning continues, its details are more noticeable in behavior than in appearance.

solto-karamoin

Before asha, the widow does not wear an elechek, but instead puts on a black zholuk (black scarf), and over it a white one. Then her relatives buy her a new scarf, and then she again wears an elechek, which is small in size.

If the widow intends to remarry, she wears an elechek without egalgych. If not, she wears a normal head covering. Thus, the difference in attire between a married woman and a widow lies only in the size of the elechek.

kainazar

On the widow's head, instead of an elechek, there is a black scarf (if the husband was an old man) or a red one (if the husband died young).

A woman mourning for her husband wears a black scarf (kara zholuk); a woman mourning for another person, for example, for a son, wears a white scarf.

Mourners

Not all widows know how to lament. Therefore, mourners (yilauker khatyn) are invited to the funeral. A mourner (for example, a widow) never sits on the ground, but on a bed or something else. She supports her sides with both hands and leans her body forward. Among the Kara-Kyrgyz, the widow must sit on the ground with her back to the door; her left hand rests on her bent left leg; her right foot is placed flat on the ground. The elbow of her right arm rests on her right knee, supporting her cheek37...

Mourning Colors

Karako

In earlier times, after the death of a man over 50 years old, the mourning color of his widow's clothing was white (? — F.F.); if younger than 50 years, the woman wore a red or black zholuk38.

Songköl kydyr,

buku

The mourning attire of the widow of an elderly person is all black; the widow of a young person dresses in red (without an elechek).

Kokomeran

sajak

The widow covers her head with a blue or white scarf... Across the forehead, it is tied, for example, with a black ribbon.

Songköl

sajak

The color of a woman's mourning clothing is black. One of the elements of mourning clothing is a black ribbon across the forehead. The color can be red and white (? — F.F.).

Osh District

Black clothing, black kyl'drouch around the yurt, the door is black or green.

kainazar

A dark shirt, a blue or black scarf. Dressed in black or red.

Effigy of the Deceased (tul) and Property of the Deceased

Frunze Canton

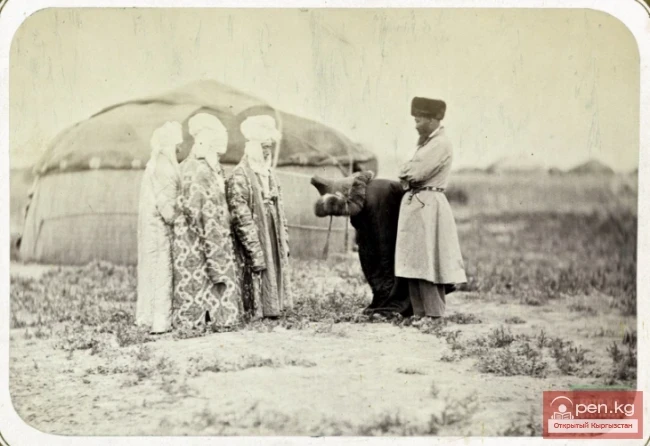

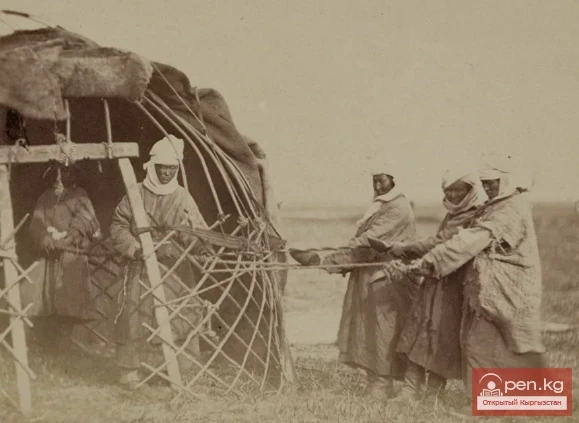

In the yurt after the death of a respected person, a crossbeam is set up, on which his best clothing is placed.

Tokuzbulak

When a wealthy person dies, a pole is set up on the right side of the tor'a40, at the edge of the zhuk, on which the deceased's best robe and hat are placed — this is his image, serving as a reminder of him. In the yurt, the best things (clothing, fabrics, jewelry) are hung on stretched ropes; such items can be borrowed if one’s own are insufficient. All this is kept in this position until asha.

Osh District

Tul was previously placed during asha on the deceased's saddled horse, tied to the yurt.

kainazar

The widow (in former times) sat by the tul for a whole year, showing herself only to relatives.

Valuable items of the deceased were also transported openly during migration.

solto-karamoin

Tul — the complete clothing of the deceased, which is hung on the alabakan in the yurt on the right side, where the host slept41, and remains until asha.

kainazar

Tul consists of a hat and chapán (the deceased's pants and boots are given to those who washed the body), hung on a shield, to the right of the zhuk. Here is also all the horse gear and the deceased's whip.

All the valuable items of the deceased are hung in the yurt. During migration, tul is transported on a camel, tied as a load (not vertically).

The best camel from the herds is chosen for this purpose.

solto-karamoin

During migrations to a new place, all the clothing (tul) of the deceased is transported on the deceased's saddled horse.

Tul is removed 7-10 days after asha, during which livestock is slaughtered and a feast is prepared.

The custom is currently in a state of disappearance.

... If a man dies in the house, and especially if he is the head of the family, until the memorial service is held..., the following is done. In the house or yurt of the deceased, a corner is separated with a curtain, where on a vertically placed pillow, the deceased's robe is put on, above it — a chalm made for wearing. This is a likeness of a doll and is supposed to represent the deceased, continuing to be among his people awaiting the memorial service. People approach the corner where the doll is located with respect. One kasanets (a resident of the village of Kasan in the Fergana Valley. — B.K., S.G.) told me that in a Kyrgyz family in the Todzher area (near the village of Bayastan), he saw such an image of the deceased, even though more than a year had passed since his death. It turns out they could not gather yet to hold the corresponding memorial service.

The Personal Horse of the Deceased

Songköl

sajak

During chong asha, the favorite horse of the deceased was slaughtered, and its meat was eaten together with other meat45.

The deceased's horse is set free into the herd, or his son or someone from close relatives rides it (during migration). It is slaughtered last at asha, while the Quran is recited.

solto-karamoin

The deceased's own horse, along with all other property, remains in his aul when the widow remarries. Some, however, slaughter it during asha.

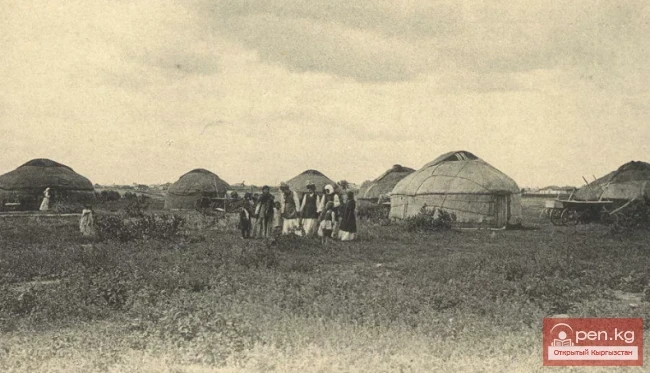

Mourning Decoration of the Yurt

Naryn

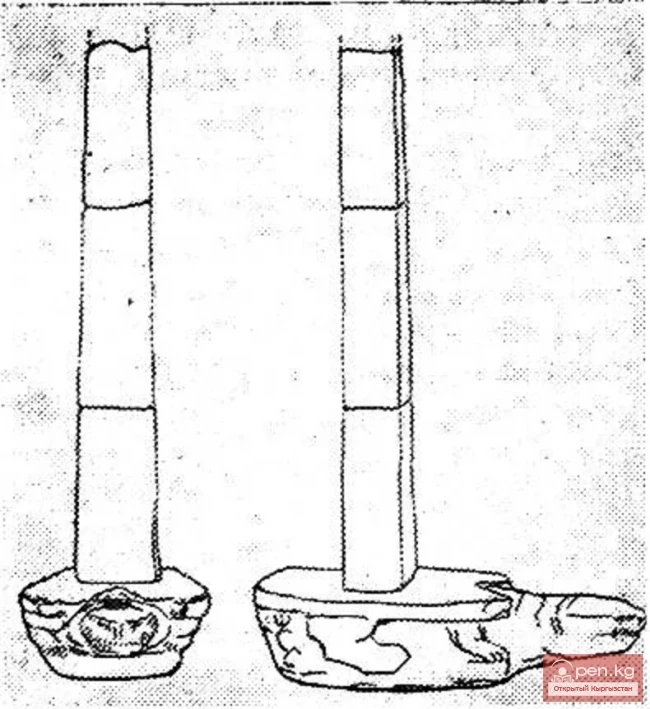

Tuu — a sign (banner) indicating that a person has died in the yurt. It consists of a pole to which the tail of a yak or foal and a piece of white cloth are attached. It is later received by the winner of the first prize in the horse races at asha46.

In the event of someone's death, a black ribbon is stretched along the lower edge of the yurt. Jilek — a white scarf that is displayed outside the yurt on a pole — kazak (spear), set inside and passed through a hole made in the felt. During migration, a young man carries this spear with the jilek in front, and all the women following cry, etc. The jilek is kept until asha.

Songköl

sajak

Jilek (scarf) — red or black, or in extreme cases, white if there is no other. The scarf is only hung if the deceased is a man.

Osh District

The doors of the mourning yurt (etik) are painted black or green (? — F.F.) and around the yurt is a black kyl'drouch (fringe).

kainazar

The tuu stands at the bottom of the yurt on the right: ak if the deceased was old, kyzyl tuu — if young.

Tuu — the spear (nail) of the deceased, under the tip of which is the tail of a yak. During migration, it is carried by a close friend of the widow beside her, while she cries. After asha, the tuu is broken and burned in the kemge, where meat was cooked for the memorial service.

According to E.A. Alexandrov, a black scarf hangs over the yurt of the deceased for a whole year.

[i]Comments:

30 Bayga — horse races. Previously, they had not a sporting but an exclusively ritual character and were held only at memorial services. As prizes, items belonging to the deceased were given (Lipie R.S. Images of the hero and his horse in Turkic-Mongolian epic. Moscow, 1984. P. 222; Basybaov V.N., Karmysheva Dzh.H., Religious beliefs // Kazakhs. Historical and ethnographic study, Almaty, 1995, P. 262-263). Kim boru — goat races, "goat herding" — in a ritual sense, were more related to wedding celebrations (Simakov G.N. Social functions of Kyrgyz folk entertainments at the end of the 19th — beginning of the 20th century. Historical and ethnographic essays. L., 1984. P. 149-150). Over time, both began to be held on every favorable occasion.

31 See note 48.

32 An elderly baibiche does not lament for her husband. It is unclear why.

33 The taboo on people in mourning, including widows (widowers), was known to many peoples of the world and was associated with fear of the ghost that supposedly is nearby the tabooed (Frazer J. Op. cit. P. 234-237). Widowers (widows) lost all civil rights during the mourning period. They were not allowed to appear in public, pass through the village, or communicate with the outside world, cultivate gardens, engage in household activities, etc. They could do anything only at night and in complete solitude. No one was to see them (Frazer J. Op. cit. P. 23).

In several villages of the Fergana Valley, all women, family members of the deceased, had to stay in the house of the deceased for 40 days, leaving their families in the care of their husbands and his relatives. They could only visit their families at night (Karmysheva B.H. Archaic symbolism... P. 148). Among the Khakas, the widow for 40 days not only was not allowed to engage in household affairs, communicate with relatives, neighbors, but generally seemed to be under the power of the otherworldly and lost her human form: she wore clothes inside out, let her braids down, as was done with the deceased. The end of her mourning was framed by her return to the world of the living (Traditional worldview of the Turks. II. P. 162).

The last report seems more accurate to us. The widow (widower) and the closest relatives of the deceased seemed to also leave this world for the other world, and therefore, naturally, they could not communicate with people or engage in earthly affairs. It was not the ghost of the deceased that was near them, but they themselves were "deceased" and therefore instilled fear in those around them, and thus were tabooed. In our case, the Kyrgyz widow only needed to turn her face away from outsiders, but not from those from the same aul, which indicates a certain transformation of the rite. But entering the "black yurt," i.e., the yurt where household activities are conducted, food is cooked, was forbidden for her.

34 This is probably explained by the Zoroastrian notion of the impurity of the corpse and everything that comes into contact with it.

35 Elechek — a head covering for a married woman. Since the widow is no longer such, she presumably should not wear an elechek, and the scarf, being also a head covering for a married woman, is also an element of mourning clothing (note the record of F.A. Fielstrup: "A girl wears a scarf after her father's death").

36 A married daughter in mourning for her father does not let her hair down, perhaps because she now belongs to her husband's kin, not her father's.

37 It is unclear why among the Kazakhs the mourner does not sit on the ground, while among the Kyrgyz she must sit on the ground.

38 On the semantics of the colors of mourning clothing among the Kyrgyz, Kazakhs, Tajiks, see Bayaieva T.D. Op. cit. P. 69-70; Pisarchik A.K. Death... P. 161; Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. P. 105-106.

39 Tul — a symbolic representation of the deceased during mourning (up to one year) in the form of a doll (crossbeam or pillow dressed in the deceased's clothing) — is a very ancient institution in funerary and memorial rites and is known to many peoples of the world (Abramzon S.M. Kyrgyz... P. 328-337; Shishlo B.P. Central Asian tul and its Siberian parallels // Pre-Islamic beliefs and rituals in Central Asia. JVL, 1975; Basybaov V.N., Karmysheva Dzh.H. Op. cit. P. 259-260; Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. P. 106-112). It is assumed that the "doll" is a vessel for the soul of the deceased (more precisely, the vessel is the clothing it is dressed in) and therefore it (the doll) serves as a temporary substitute for the deceased on earth.

The spear of the deceased, displayed from the yurt with a mourning "flag" (see below), the favorite horse, and the clothing hung in the yurt also play the role of a temporary substitute for the deceased (Shishlo B.P. Op. cit. P. 249; Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. P. 109). It seems that this role is also played by the mourning staff that those mourning the deceased lean on (see note 2). This thought is suggested by the following information: 1) after her husband's death, a Kazakh woman sewed a rag doll, before which she cries and laments daily, and in the evening lays it with her in bed (Potanin T.N. Essays on northwestern Mongolia. St. Petersburg, 1883. Vol. IV. P. 99); 2) among the Khakas, the widow every evening during the mourning period laid the mourning staff next to her (Usmanova M.S. Khakas // Family rituals of the peoples of Siberia. An attempt at comparative study. Moscow, 1986. P. 113).

The emergence of the institution of "temporary substitute for the deceased" is linked by S.M. Abramzon to the cult of ancestors (Abramzon S.M. Kyrgyz... P. 335-337). B.P. Shishlo argues with him, believing that the emergence of tul is not related to the cult of ancestors, but only to the idea of fear of the deceased, as evidenced, in his opinion, by the destruction of tul (both the doll and the spear) on the anniversary of death, which signifies the final break between the deceased and the living (Shishlo B.P. Op. cit. P. 257-258).

Without entering into polemics, we would nevertheless like to draw attention to the analogy that B.P. Shishlo draws between the Kyrgyz-Kazakh custom of breaking the spear and wooden parts of the tul after the mourning period and burning them, and the Australian rite of breaking the bones of the deceased, after which the spirit of the deceased forever returns to the place of residence of other spirits, where it was supposed to be (Shishlo B.P. Op. cit. P. 257).

In this regard, let us recall that many ancient peoples had a very definite notion of the bones of animals and humans: preserved intact (not broken or cut), they have the ability to grow flesh and be reborn. Destroyed bones, however, are a sure way to achieve complete non-existence of the animal or human (Frazer J. Op. cit. P. 587-588; Traditional worldview of the Turks. II P. 67-68). If it was necessary to eradicate an enemy clan forever, it was not enough to kill it; it was necessary to destroy and chop its bones.

Thus, Australians broke the bones of the deceased, while Kazakhs and Kyrgyz (and other Turkic peoples) broke the spear of the deceased and the wooden parts of the tul, symbolizing the skeleton of the deceased, so that he (the deceased) would no longer wander the earth and harm the surviving living relatives. Thus, the driving force behind these actions was fear. And in this, B.P. Shishlo was apparently right.

On the other hand, burning the bones is not only the complete destruction of their owner but also a remnant of the ancient way of burying the deceased and the only way to send his soul with the smoke of fire upwards (Potapov L.P. Essays... P. 373; Traditional worldview of the Turks. II. P. 69). And this relates to the cult of ancestors.

Most likely, we are dealing with a contamination of two different reasons for the emergence of this rite, and therefore both scholars are correct.

40 That is, where the deceased lay.

41 Apparently, the side in the yurt is determined in this case from the entrance (see note 13). K.K. Yudakhin pointed out that the tul was placed above the place of the marital bed (Yudakhin K.K. Op. cit. P. 764), while A.T. Toleubaev — on the tbr'e itself (Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. P. 154).

42 See note 48.

43 As they protest during the breaking of the spear, since the items, as already mentioned, are also vessels for the soul of the deceased and play the role of a temporary substitute for the deceased. And women do not want to part with even the substitute of the deceased.

44 Sep — one of the meanings of this word in modern Kyrgyz is "bride's dowry." Few informants know that personal belongings of the deceased were previously called this (which, as we see, were also hung for viewing), it has been forgotten. This is not noted in K.K. Yudakhin's dictionary. It is not surprising that F.A. Fielstrup placed a question mark in parentheses.

45 On the role of the horse in funerary memorial rites see: Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. P. 137-148.

46 Tuu — the spear of the deceased or a pole with a scarf at the end is not only a sign indicating that there is a deceased in the house, but also a temporary substitute for the deceased, just like his clothing, tul, and favorite horse. The color of the scarf on the spear indicates the age of the deceased: white means an old or elderly person died, black means a middle-aged person (i.e., a person with a black beard), red means a young person (Bayaieva T.D. Op. cit. P. 70; Simakov T.N. Social functions... P. 142; Basybaov V.N., Karmysheva Dzh.H. Op. cit. P. 259; Toleubaev A.T. Op. cit. P. 106).

Burial. Ritual Life of the Kyrgyz in the Early 20th Century. Part - 14