The Idea of the Unity of Deities

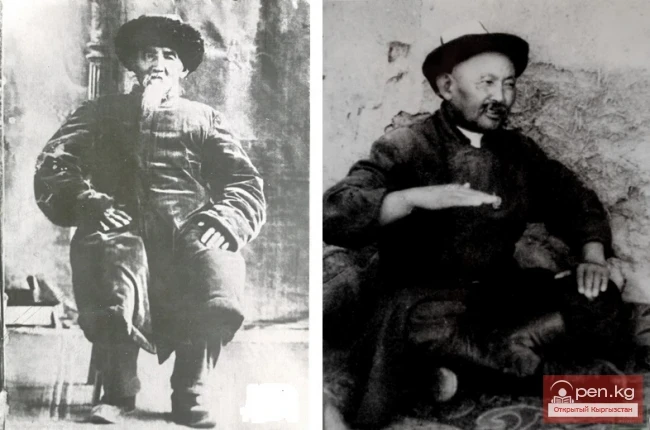

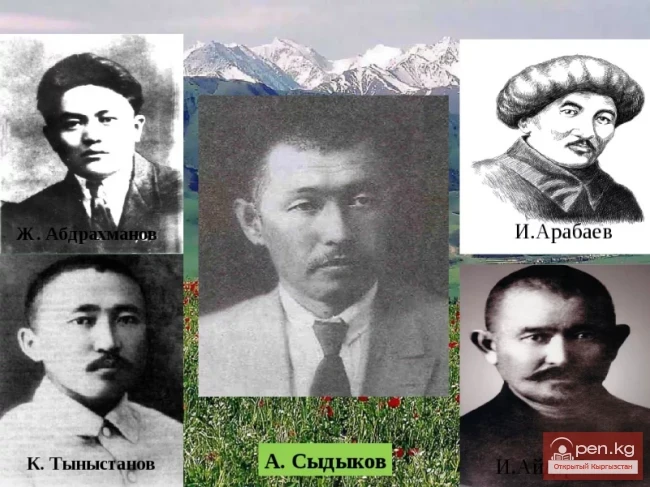

The storytellers of "Manas," like shamans and mullahs, also performed the functions of a healer. This is known from the biographical data of the storytellers Keldibek and Sagymbay.

Can we conclude from all this that the storytellers of "Manas" inherited these customs from shamans or imitated mullahs? In our opinion, the reason lies deeper. Here, the same idea of selection is at play, which was wonderfully analyzed by the famous ethnographer, Professor L. Ya. Shternberg: "This idea is rooted primarily in the worldview of primitive man. Since the time when man discovered the existence of special beings in the surrounding world - spirits - and in the volitional acts of these last ones began to see the reasons for all occurring phenomena, he began to attribute all his life successes and misfortunes to the direct intervention of those or other spirits.

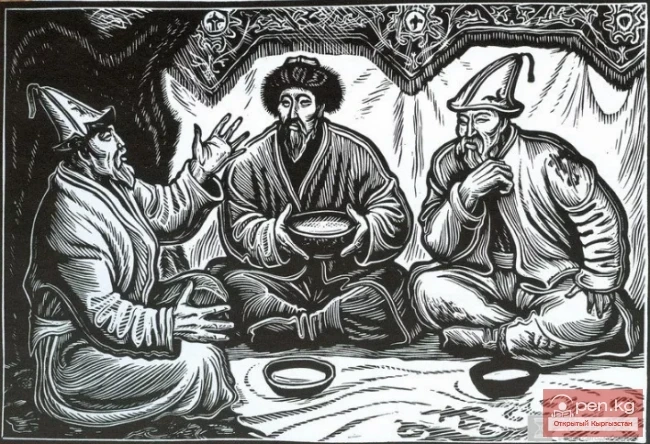

The further development and completion of this idea was achieved in connection with the representation of the possibility of direct communication between man and the representatives of the world of spirits. Thanks to this communication, the chosen one acquires supernatural powers, becomes an intermediary between people and deities, and finally proclaims their will, teachings, and commands. Hence - the idea of the unity of deities, the idea of revelation, the idea of god-humanity, ideas that gave rise to shamans, priests, prophets, founders of religions."

Another researcher of the issue of selection, I. N. Vinnikov, divides selection into two types: passive and active. He calls passive those cases when the chosen one is accepted for the performance of his function under the threat of the protective spirit, in this case - Manas or his close ones. The author believes that the passive type is more ancient and has roots in the primitive clan structure. As for the active type of selection, here the shaman or another representative of the cult himself strives to be chosen by his protective spirit and for this leads a corresponding way of life (unity, wandering, etc.). This type of selection, I. N. Vinnikov considers a product of a later era and sees the reason for the transition from passive to active in the fact that, in connection with the growth of wealth in society, shamanism is transforming into a profession.

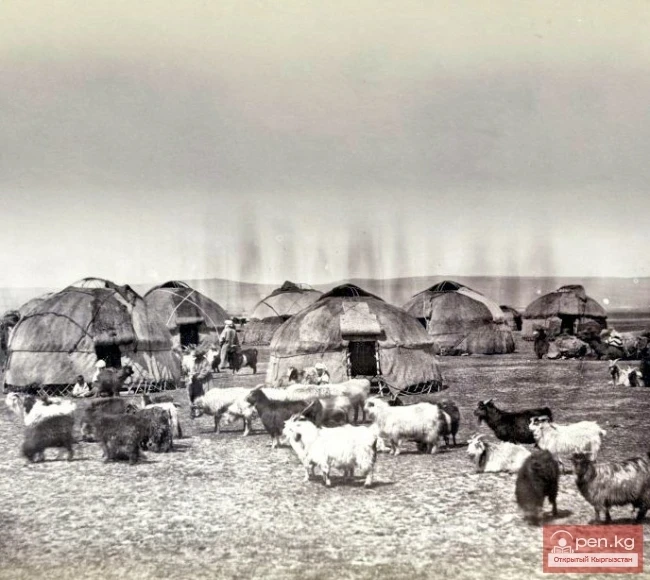

If we consider the phenomenon of manaschi from this point of view, it should be attributed to the passive type, because dreams are almost always accompanied by an open or hidden threat. However, there are also cases, for example, among the storytellers Balik, Sayakbay, Shapak (...), when dreams were not accompanied by an open threat, yet those who saw them did not show an active desire to be chosen. On the other hand, almost all storytellers - both those who were threatened in dreams and those who were not - were greater admirers of "Manas" and wanted to become manaschi. In any case, in dreams, the passive type of selection predominates, and if it is correctly attributed to the more ancient type, then its prevalence among our storytellers is explained, apparently, by the presence among the Kyrgyz people of very significant clan traditions.

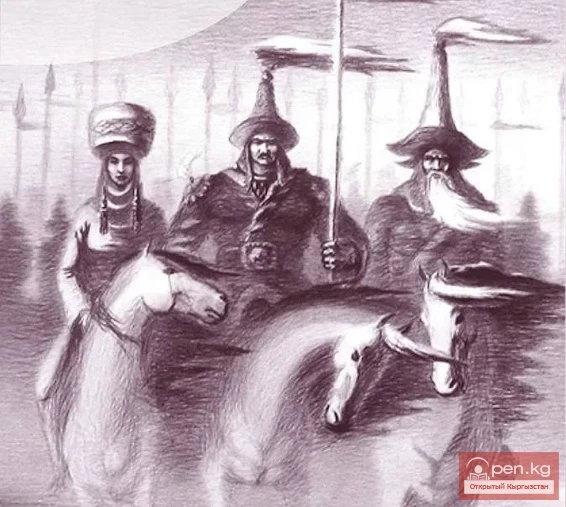

Thus, the legends about dreams are nothing other than a special glorification of Manas, when he transforms into a protective spirit, and the storytellers - into his chosen ones. This once again confirms the enormous authority of the epic in the eyes of the popular masses, who see in Manas a great protector and consider him a symbol of goodness and happiness.

It is also interesting to try to clarify how much these dreams correspond to reality. Does the storyteller see the dream before he begins to recite "Manas"? We tend to consider this a quite possible phenomenon, and here’s why. Firstly, all the known storytellers we have had no education, and only a few of them barely learned to read sacred books from mullahs. Consequently, they deeply believed in the supernatural, including in dreams, visions, and selection. This belief was supported by numerous tales about dreams, the greatness of Manas, and his close ones. Secondly, the storyteller, in the majority, being a youth of 15-16 years, preparing to become a akyn-manachi, experienced a special period of creative rise, because before he began to perform "Manas," he had to master this greatest work, which, of course, required great tension of the nervous system. If we take all this into account, it will not seem strange why the young storyteller had dreams of Manas and his close ones. But, of course, the creativity of the storyteller was not caused by dreams; on the contrary, dreams were caused by the tense creative activity in preparation for the role of the storyteller.

Biographical data about manaschi bring full clarity to this question. From them, we know that the storytellers, even before they began to perform "Manas," were already akyns-singers, i.e., creative figures; moreover, each of them went through a stage of familiarization, study, and mastering the content and artistic techniques of the epic, listening to it in the performance of predecessors. This is mentioned in the biography of almost every storyteller, and they themselves do not deny that listening to this or that prominent manaschi, they simultaneously learned from him, however, they again make a reservation: "Although we learned from others, we only began to sing 'Manas' after the dream." This explanation is understandable: the convinced storyteller of the necessity of the vision, perhaps, did not dare to begin performing "Manas" until the traditional dream occurred, under which, by the way, a professional secret may be concealed.

Here it is necessary to pause on one more question. Some storytellers have a tendency to explain dreams by simple material or career-related considerations, which in this way aimed to elevate themselves above other akyns and thus protect themselves from possible persecutions from the side of beys-manaps, who held a high opinion of akyns-singers, subjecting them to persecutions, mockery, etc. Otherwise, it was suggested that dreams, as such, had no place, and this was merely a fabrication for self-glorification.

Persecutions against akyns from the side of beys and manaps were indeed a frequent phenomenon, which can be confirmed by many facts. However, there were also cases in reverse. For example, storytellers Balik, Tynybek, and Sarymbai enjoyed great respect, and the first two, precisely because of their profession as storytellers, rose to the position of the ruling elite.

However, alongside this, there are known facts when storytellers referred to dreams with the aim of defending their creativity.

Such was the case with Sagymbay, when nationalist elements demanded to include a number of new episodes in "Manas," like the struggle of Manas with Napoleon, etc. Sagymbay categorically refused, stating that because of this he lost his poetic gift and could only regain it through a sacrificial offering, i.e., after he slaughtered a ram, dedicating it to Manas, and once again saw a dream.

Indeed, the position of the storyteller of "Manas" could give him an advantage over other akyns, because the epic itself, as we have seen, was almost deified. However, this does not have a direct relation to dreams.

The latter had deeper roots, about which we have already spoken. But storytellers could also use dreams in this way, as Sagymbay did.

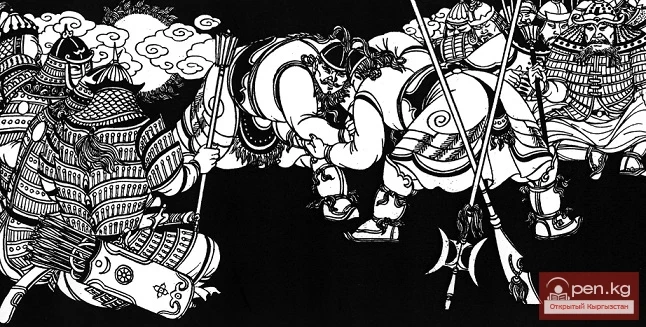

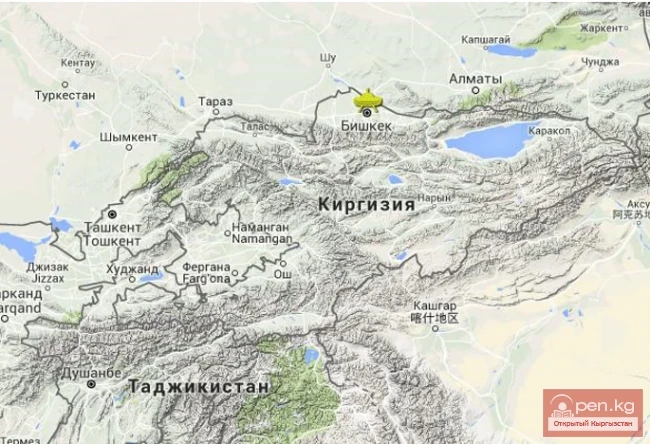

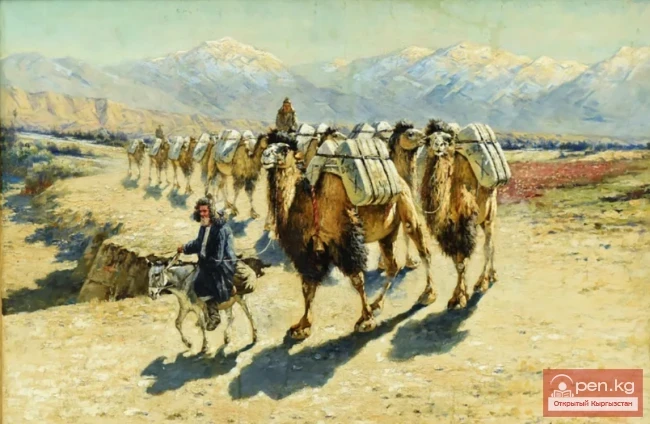

Kyrgyz Heroic Epic "Manas"