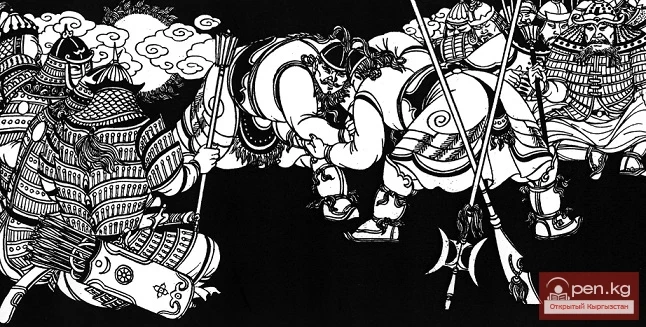

Historical Canvas of the Epic "Manas"

In starting the characterization of the historical canvas of the epic "Manas," we pointed out that all events are intertwined around the name associated with the greatest successes and a turning point in the history of the Kyrgyz people. Based on Chinese sources on one side and ancient-Gurkhan texts from the Selenga River on the other, we assert that the Kyrgyz khan, with his talented leadership, ensured the victory of the Kyrgyz, known to the Chinese by the name Tunge Pizze Gin and posthumously titled Zun-in Xun-nu Chem-Min Khan, mentioned on the gravestone of Yaglakar-khan, is one and the same person. With this outstanding personality, during whose lifetime the Kyrgyz emerged as an active political force far beyond the borders of Yenisei, in the middle of the 9th century, the "genealogy" of the epic begins. It is not excluded that the name of the hero after whom the epic is named is a historical name. In Manas, we see the Syrian name Mani - the founder of the Manichean teaching, synonymous with teacher. In light of modern scientific data, Western influences among the Kyrgyz and on the Yenisei acquire significant interest.

Findings in the Copenhagen Chaatase finally confirmed the thesis of Iranian-Chinese connections of the Kyrgyz, while inscriptions on the rocks of the Yenisei during the time of the Kyrgyz speak of Parthian-Sakan connections and ancient ties with the Near East.

The works of Shavanna and Pell showed the enormous role of Manichean teachings in Central Asia, where the first and most zealous disseminators of Manichaeism were the Uyghurs, evidenced by numerous Manichean compositions in Turkic languages. The presence of Syrian preachers - teachers is documented, and a Kyrgyz inscription on the grave of the Kyrgyz Boyla, son of Tarkhan, is a testament to this. Not only through Semirechye, but also through Eastern Turkestan and Mongolia, the Kyrgyz could become acquainted with Manichaeism, this mixture of Christianity, Buddhism, and Zoroastrianism, and found their reflection in the form of motifs of Manicheans in the visual arts of Eastern Turkestan (for example, frescoes of Khoja and Kyzyl in Kuchare).

Yaglakar, having accepted Manichaeism (which his son also honors, as evidenced by an inscription found in the Selenga region), thus becomes in the eyes of the people a descendant of Western origin, i.e., a Western Turk-Nogai. In genealogy, this name could have come from Chinese sources. We know this name from Chinese sources of the late 5th century, as the name of the uncle of the Zhuzhan khan Deulun, who defeated the Gaojuy tribe west of Altai in 491 AD. Thus, the name Horai in the genealogy of Manas could have Eastern origins. However, subsequently, the people interpreted this name as belonging to the Nogai - Western Turks, seeing in this a Kyrgyz origin of Manas, which, from our point of view, would be incorrect.

The combination of an unknown name for the Kyrgyz, the origin of which has faded from the memory of the people, the presence in its genealogy of a predecessor identical to the tribal name of Western Turks, created that incredible confusion when the hero of the national epic becomes a foreigner.

Manas is constantly surrounded by conspiracies and attempts by the side of the dead to eliminate him. His motives for the campaigns are noble: he wants to free the people from poverty, eliminate the threat of their enslavement by the Chinese and Kalmyks.

Manas leads his relatives on the path to freedom, for example, the clan of Kezkoman. He does not refuse to form a coalition with other peoples for the sake of these noble deeds. Such methods are historically not unique. Regarding the Iranian epic, V. Barthold wrote: "The revival of the Iranian epic, as is known, is one of the first signs of the revival of Iranian nationality."

A similar picture is seen with the epic "Manas." As can be seen from the above, it vividly presents two categories of facts - the main periods of the political rise of the Kyrgyz people in the struggle for independence in the 8th-9th centuries and the 17th-19th centuries. It can be assumed that it was during these periods or immediately after them that the epic particularly intensively developed, enriched, becoming an effective means of educating the Kyrgyz people in the spirit of heroism and martial valor. This assumption does not exclude the fact that the epic tradition manifested itself in the creativity of folk storytellers during the interval between these two periods.

Thus, we expressed the consideration that the epic reflects two periods of Kyrgyz history - periods of their greatest activity in the struggle for independence. The epic is not a passionless chronicle of events but an emotional reflection of reality.

Expressing the aspirations of the people, it could, apparently, in its main parts rely on the best periods of its history.

This is all the more likely regarding the epoch when the epic begins to take shape, as separate legends and traditions seek a worthy and significant figure in the history of the people, which can become at the head of all events, even if they occurred much later in his actual life, to begin the narration from him. As noted above, the earliest chain of historical events ties the epic to the 8th-9th centuries, and gives it beyond the Tian Shan.

The most likely starting figure, around which the connection of the epic could form, is the figure of Yaglakar, during the 8th-9th centuries, territory-Central Asia, specifically the Yenisei, Mongolia, Altai.

"Manas" - the era of the emergence of the epic