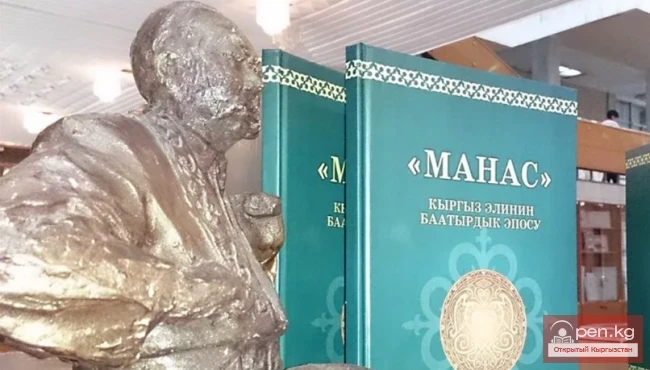

"MANAS": LANGUAGE AND STYLE OF THE EPIC

The text is taken from B. M. Yunusaliev's article "The Kyrgyz Heroic Epic 'Manas'"

The Kyrgyz people have every right to be proud of the richness and diversity of oral poetic creativity, the pinnacle of which is the epic "Manas." Unlike the epics of many other nations, "Manas" is composed entirely in verse, which further attests to the special respect the Kyrgyz have for the art of versification.

The epic consists of half a million lines of poetry and surpasses all known world epics in volume—20 times larger than the "Iliad" and "Odyssey," 5 times larger than the "Shahnameh," and 2.5 times larger than the Indian "Mahabharata."

The grandeur of the epic "Manas" is one of the distinguishing features of the epic creativity of the Kyrgyz. (...)

The poetic techniques of the epic correspond to its heroic content and the grandeur of its volume. Each episode, often representing a thematically and fabulously self-contained poem, is divided into songs-chapters. At the beginning of a chapter, we have a unique introduction, prelude, polyprosaic and polyphonic form (jorgo sez), where alliteration or final rhyme is observed, but size is absent.

Gradually, the jorgo sez transitions into rhythmic verse, the number of syllables of which varies from seven to nine, corresponding to the rhythm and melodic music characteristic of the epic. Each line, depending on the fluctuation of the number of syllables, is divided into two rhythmic groups, each of which has its musical accent, not coinciding with the expressive accent. The first musical accent falls on the second syllable of the first rhythmic group, and the second—on the first syllable of the second rhythmic group. This arrangement gives strict symmetry to the entire poem. The rhythmic quality of the verse is supported by the final rhyme, which can sometimes be replaced by an initial euphony—by alliteration or assonance. Often, the rhyme is accompanied by alliteration or assonance. Sometimes we observe a rare combination of all types of euphony—along with the final rhyme, external and internal alliteration:

Kanatyn kayra kakkyla,

Kuyryn kumga chapkyla...

The stanza has a varying number of lines, most often it appears in the form of a single-rhymed long tirade, which provides the storyteller with the necessary tempo for performance. Other forms of organizing the poetic structure (refrain, anaphora, epiphora, etc.) are also used in the epic.

In creating images, various artistic techniques are employed. The heroes are depicted dynamically—in direct actions, in struggles, in clashes with enemies. The landscapes of nature, meetings, battles, and the psychological state of the characters are conveyed mainly through narration and serve as additional means for portrait characteristics.

A favorite technique in recording portraits is antithesis with a wide use of epithets, including constant ones, for example, "kan zhyttangan"—the one smelling of blood (to Konurbay), "dan zhyttangan"—the one smelling of grain (to Jolo, hinting at his abundance); "Kapilllete sez tapkan, Karangyda kez tapkan" (to Bakai)—seeing in darkness, finding a way out in a hopeless situation.

As for the style, it is necessary to note that alongside the prevailing heroic tone of the narrative, there is a lyrical description of nature, and in the poem "Semetey"—even romantic love. Depending on the content, commonly used folk genre forms are successfully employed in the epic, such as kereez (testament) at the beginning of the episode "Remembrance of Koketey," arman (lament song about fate), for example, the arman of Almaambet during the division with Chubak in "The Great Campaign," sanat—a song of philosophical content, and others.

Hyperbole predominates as a means of depicting heroes and their actions. Hyperbolic dimensions surpass all known epic techniques. Here we deal with an extremely fabulous exaggeration.

The wide and always appropriate use of epithets; comparisons, metaphors, aphorisms, and other expressive means of influence further captivate the appreciative listener of "Manas."

The language of the poem is quite accessible to the modern generation. The accessibility and simplicity of it can be explained by the fact that the epic lived in the mouths of every generation. Its performers, being representatives of a certain dialect, performed before the people in a language understandable to them.

Despite this, the lexicon contains a considerable amount of archaic, which speaks to its thousand-year existence. From the historical perspective, it is precisely the lexical archaisms that represent a particular interest—they can serve as material for the restoration of ancient toponymy, ethnonymy, and onomastics of the Kyrgyz people. The lexicon of the epic reflects various changes in the cultural-economic and political relations of the Kyrgyz with other peoples. One can find many words of Iranian and Arabic origin, words common to the languages of Central Asian peoples. There is a noticeable influence of the literary language, especially in the variant of Sagynbay Orozbakov, who was literate and showed a particular interest in literary sources. The lexicon of "Manas" is not devoid of neologisms and Russisms.

For example, mamont from Russian "мамонт," ulekper from Russian "лекарь," zymrut from Russian "изюмруд," etc. At the same time, each storyteller preserves the peculiarities of their dialect.

Syntactic peculiarities of the language of the epic are connected with the grandeur of its volume. To enhance the tempo of the poetic material's exposition, long constructions with numerous participles, gerunds, and introductory clauses are widely used, sometimes in unusual combinations. Such a sentence can consist of three or more dozen lines. In the text of the epic, there are characteristic violations of grammatical connection (anacoluthon), caused by the necessity to preserve the size of the verse or rhyme.

Overall, the language of the epic is expressive and figurative, rich in nuances, as the best talents of the folk eloquence of previous epochs have labored over its polishing. The epic "Manas," as the largest monument, has absorbed all the best and valuable from the verbal-cultural heritage of the people, has played and continues to play an invaluable role in shaping the common national language, in bringing its dialects closer, in refining grammatical norms, in enriching the vocabulary and phraseology of the common Kyrgyz literary language, which developed after the Great October Socialist Revolution.

The historical and cultural significance of the epic "Manas" lies also in the fact that it has had a substantial influence over the centuries on the formation of aesthetic tastes and the national character of the Kyrgyz people. The epic instills in listeners (readers) a love for everything beautiful, elevated, a taste for art, poetry, music, the beauty of human qualities (diligence, heroism, bravery, patriotism, loyalty to one another), a love for real life, and the beauty of nature. Therefore, it is not accidental that the epic serves as a source of inspiration for masters of Kyrgyz Soviet art in creating artistic works (for example, A. Tokombaev's poem "About the 28 Heroes-Panfilovtsy"), operas ("Aychurek," "Manas" by Maldybaev, Vlasov, and Fere), films.

The epic teaches its listeners ethical norms of behavior. Favorite images—Manas, Kanykey, Bakai, Almaambet, Semetey, Külchoro, Aychurek, Seytek, and others—are immortal primarily because they possess such high moral qualities as boundless love for the homeland, honesty, bravery, hatred of invaders, and traitors. The heroic epic "Manas," thanks to its high artistry, rightfully occupies a worthy place on the shelf of world masterpieces of oral creativity.

"MANAS": Mythology and Fantasy