Hero of the Soviet Union Grigory Isayevich Vygлазов

Grigory Isayevich Vygлазov was born in 1919 in the village of Shaydarovo, Suzunsky District, Novosibirsk Oblast, into a peasant family. He was Russian and a Komsomol member. He moved with his family to Kyrgyzstan, to the village of Gulcha in the Aksy District of Osh Oblast. He was drafted into the Soviet Army in 1939. He served as a private and a squad commander in a parachute battalion.

During the Great Patriotic War, he distinguished himself in battles on the North Caucasian Front while defending Kerch. Together with his squad, he repeatedly went on reconnaissance behind enemy lines, delivering important information to the command.

On February 22, 1943, for his bravery, courage, and heroism displayed while carrying out a combat mission, he was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

DID NOT RETURN FROM BATTLE...

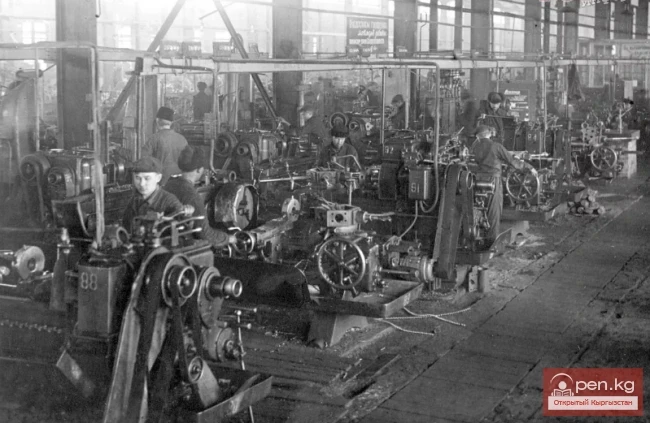

The agronomist drives the UAZ himself. This no longer surprises anyone: young people can do many things and know a lot. There are no roads; we travel from one mountain to another. We want to see the haymaking. Ah, there go the mowers. Around the bend, we saw the "Kyrgyzstani." The baler was "swallowing" a swath of soft hay and occasionally ejecting a huge grass brick, tightly bound with twine. It’s not hot: cool air streams from the distant snowfields.

It smells of withering grass. Somewhere, birds are chirping. A group of guys approached a wooden barrel by the road. They drink water, laugh, and start splashing each other with mugs. A cheerful commotion. A break during haymaking.

And suddenly—a strange, strong, and sharp metallic clang. Something is not like the usual noise of a working day.

The agronomist turns onto the ridge of the mountain, and everything becomes clear. Some guys are peacefully mowing, raking, and baling. They are working. Others are learning to defend peaceful labor—everything is as it should be. A tank, equipped with everything necessary for training combat, turned on one track, clearing a path for the next one that was coming up behind it. A trench, stationary and moving targets. And we heard the clang of a cast iron shell that the tankers hit the metal shield with.

I look at the dusty, armored monster, and an involuntary thought comes to mind: in a real battle, can anyone or only some people blow it up? Is it really the most reliable way—to go under the tracks with a bundle of grenades? And look, the next one is turning to shoot. Who will crush it if you are already lying, pressed into the ground? No, the commander who restrained the eager soldier is right: one must win, not die. Let the invaders, the uninvited guests, die.

I wonder what kind of training and which commanders Grigory Isayevich Vygлазov, the squad commander of the separate parachute battalion of the North Caucasian Front headquarters, went through? Judging by his actions in the battles near Kerch, they taught him to win, and he learned this lesson well.

On the fronts of the Great Patriotic War, there were many such guys who, finishing their military service during peacetime, were already counting the days and months left until their discharge. They were thinking about their future plans. They counted the days they would have to spend on the road. They imagined how they would appear at the doorstep of their home and how their mother and sister would rejoice. But the roar of artillery, the clank of tracks, and the gunfire along the entire western border in June forty-one interrupted those thoughts, giving way to anger and anxiety.

Can a soldier be "unemployed" during wartime? Theoretically, yes: he does not participate in battles, does not go on combat guard. But practically, he cannot, because his thoughts are constantly there, in battle, where young guys are fighting for the freedom of the Motherland, because day after day, he is mastering military science, the science of winning, through hard work. And those who stand to the death never thought about such a tragic fate. And for some reason, he wanted to rush to their aid, to lend his shoulder to bear the burdens of battle. After that, everyone would feel better. And the war would begin to wane.

But in war, everyone has their place. For Grigory Vygлазov, that place became the suburbs of Kerch. There, as part of his military unit, he covered the crossing and evacuation of troops from the Crimean Front. What remained of Kerch was hard to call a city. And the Voykov plant could only be imagined in the mind. If one has a rich imagination. But a city is a city, and a plant is a plant. And to ensure coverage, one must know what the enemy has, what their numbers are, where the main strike is coming from, and how much equipment there is. The reconnaissance group consisted of three people. And they disappeared into the night.

The law of war: one side scouts, the other obstructs. Grigory Isayevich Vygлазov led the reconnaissance under enemy fire; their small detachment was noticed. This is good and bad. You only count the firing points when they are active. That’s good. And it’s bad because you might not return. How will your own know that the mission is accomplished? But it must be completed at all costs.

The fearless trio managed to penetrate deep into the enemy's defenses under mortar and automatic fire.

They also managed to return and report everything they had seen.

In war, as well as now in peaceful labor, one can judge the main thing by the final results. Experienced scouts felt that our fire system had changed, and the enemy's strength had weakened. They understood: it was not in vain that they had been plowing the ground with their bellies yesterday. Artillerymen, machine gunners, and mortarmen were hitting with purpose and effectiveness.

The situation on the front is fleeting and changeable. What brought success yesterday is no longer there today. Like pieces on a chessboard, forces are rearranged; something disappears there, something appears here. How does a commander sense the enemy's preparation for an attack with some supernatural intuition? Perhaps he cannot explain it, but an experienced commander feels: the enemy is up to something. Where to expect a strike? Again, it’s work for the scouts. Again, Grigory leads his guys into the enemy's position. The soldiers went on reconnaissance, brought back data, and the commander looked at the map: clear! The target of the impending attack is to cut off the approaches of our troops to the crossings at Yenikale and Opasnaya.

Now one can only guess and speculate how, under heavy fire, pressing into the ground, crawling from a crater to a hollow, excellently camouflaged, the scout approached almost close to the enemy's position. You cannot raise your head to see and count. But he raised it, saw, counted. And he even returned unharmed. Without a scratch. The information obtained allowed the command to deliver a preemptive strike and thwart the attack. This was an active, combat, and destructive cover for the transfer of our troops.

Four days—from May 12 to 16, 1942—were perhaps the most intense for those who defended Kerch. Grigory Vygлазov did not leave the battle for four days. A paratrooper. A scout. Three pre-war years of service in the army hardened him, helped him become tough, brave, and agile.

On May 16, 1942, by order of the commander of the 51st Army, the company in which Grigory Isayevich fought was tasked with attacking the enemy in the area of the city of Temirovo. This is not far from Kerch. Combat attacks are similar and yet different from one another. Different conditions, different forces, intensity of fire, and so on. The common and inevitable thing is one: you must tear your body away from the saving ground, rush out of the trench into enemy fire, manage to run, do your soldier's duty as it should be. And God forbid, during the attack, to lose heart, to extinguish your fighting spirit...

During the battle, Grigory received an order from the company commander—to cover the left flank of the attackers. Apparently, the company commander knew what he was doing. And evidently, he respected and protected his soldiers. The flank needed to be covered. Enemy tanks were moving from there. Eight armored monsters. (I wonder if they were at least remotely similar to those we are looking at with the agronomist?).

They move ominously, expertly led by enemy tankers. They won’t expose their side—don’t wait for it. What does a soldier think in such a situation? Probably remembers how many meters he threw a grenade on the training ground. Grigory let the front tank get close, about 15-20 meters. The viewing slits were already visible. He launched a bottle with a flammable mixture into it.

There was no time to watch the fire crawl across the armor, seeping into the slits—two more tanks were approaching. They also got a bottle. They caught fire. Five others turned back.

The soldier looked back: the attack was developing as planned. The armor-piercers remained to guard the departing enemy tanks.

Vygлазov joined the attack, moving ahead. He shot eight fascists almost at point-blank range; his ammunition ran out, and there was no time to change the drum, so he threw a grenade into the nearest cluster of enemy soldiers.

How many of them fell there—others counted.

The soldier fell lifeless to the ground: an enemy bullet caught him.

The award sheet for the posthumous conferral of the high title of Hero of the Soviet Union to Grigory Isayevich Vygлазov was signed by the commander of the troops of the North Caucasian Front, Marshal of the Soviet Union Semyon Mikhailovich Budyonny, and member of the Military Council of the North Caucasian Front Admiral Isakov...

...The land under Kerch is heavy and stony. It has many brotherly graves. People come to them—old and young.

To honor the memory of the fallen, to stand in mournful silence. These are the ones for whom Grigory Vygлазov and many others like him gave their lives. If not aloud, then in their minds, everyone says:

— May the earth be soft for you.

The stones will not become soft. But we have lived for forty years without war. This is perhaps the most important thing. This is what Grigory fought for. Forty years have passed since he finished his last battle, and the star of the Hero has not warmed his large, calloused hands from the shovel and the rifle.

Remember: astronomers claim that stars die. But the light from them, already dead, travels to us for a long, long time. Perhaps this is also a kind of memory that this star was, shone, lit, conversed with others like itself? And so the memory of the Heroes, who performed military feats, will remain incorruptible through the ages, warming the hearts of descendants for many generations to come.

V. ONISHCHENKO