TESTING PAMIR

Nevertheless, the members of the expedition passed Lailak - the camp of the Kara-Kyrgyz on March 23. The next day, the expedition members sent some of their Kyrgyz guides back home. “The guys sent by Moldo Bayas served us well all this time, but the time has come to send them back. We generously thanked them by organizing a lavish dinner. The leader of the Kyrgyz group named Baish, young and energetic, asked me for a 'kagaz', a paper of good service. They want to head back before the snowstorm closes the way to Alay. I gladly gave him this paper and also handed over letters to my friends. In addition, we distributed gifts to everyone for their good service. Finally, Baish and his guys knelt down and, praying, with the words 'Allahu Akbar', stood up. We shook their hands, said warm goodbyes, and soon they disappeared from sight. Their departure caused us deep sadness. We had grown fond of these brave, bold, and desperate people. Only eight of us remained, and the road ahead was long and difficult.” As L. Stroilov adds, the departure of the Kyrgyz guides had a noticeable impact, not in the best way, on the morale of the other expedition participants and significantly increased the burden, as “in the harsh conditions of Pamir, this group not only performed auxiliary work but also provided important moral support to the other travelers by their very presence.”

According to the author of the article, “Through the snows and ridges of Alay and Pamir, despite all the hardships and adversities of the journey, Bonvalot and Capu found opportunities and time for various observations of the nature of Pamir and for keeping diaries.”

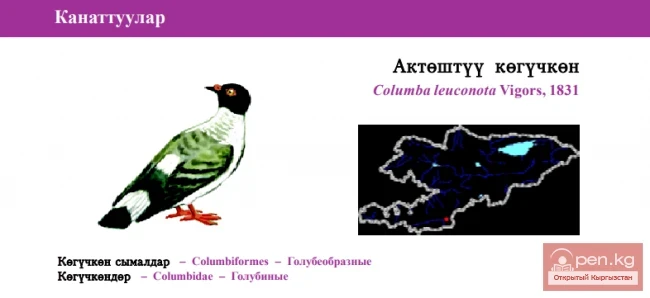

Next, the expedition approached Pamir, having passed several small lakes and acquainted themselves along the way with local Kyrgyz shrines - mazars. Here is how the author of the notes describes some of these abandoned graves. “Suddenly, a row of clay structures with domes appeared before us. Satykul proudly informed us that this is a cemetery belonging to the Teit tribe. The monuments on the graves were built by the relatives of the rich and powerful deceased. It seems to me that the only thing worthy of being immortalized on these peaks is death. In fact, life here is a strange exception. People in these places are constantly on the brink of life and death, battling the forces of nature. The inhabitants of Pamir, the Kyrgyz, are accustomed to living under the power of a mighty natural force that can dispose of them at any moment as it pleases. Perhaps that is why they know better than anyone else the value of life and death. The cemetery stretched from southwest to northeast so that the faces of the deceased looked towards Mecca. I counted four mausoleums as tall as yurts. Here, it is not allowed to build higher. The architecture is very simple, the only decoration being the horns of argali. On one of the mausoleums, a dove was carved. A dove - and at such a height!”

And here is a strange character that the travelers encountered on their way to their final high-altitude trial - the Ak-Suu valley: “A piercing icy wind cuts to the bone. Suddenly, in the midst of this eerie landscape, I saw an old woman. When I came level with her, she looked at me lazily and without interest. 'She must be a Pamir witch,' I thought. She was a sturdy, short woman with small eyes, dressed in a sheepskin coat. Only the white turban on her head indicated her belonging to the female gender. The sight was all the more mystical because around her were scattered the skeletons of sheep, horses, argali, and camels. And she herself among this looked like a dried mummy, a messenger of death. But she was an earthly woman, a Kyrgyz from the Pamir Teit tribe.” To this picture, it is worth adding L. Stroilov's description of Capu's Pamir Kyrgyz: “None of the Kyrgyz we met here was as plump as the Alay Kyrgyz or their lowland relatives. They all looked dry and emaciated, and sometimes even gaunt. Teenagers of fifteen or sixteen years seemed like little old men who had stopped growing... all of those we saw had remarkably poor teeth with exposed roots and chips. This defect, according to Capu, was caused by the consumption of snow and glacial water, as well as a meager diet lacking rice.”

The journey continued south, into the valleys. Gradually, the permafrost of the mountain glaciers began to give way to another landscape. “The first shrubs appeared - artemisias, which usually grow in the steppes. What a delight it is to breathe in their scent after all we have experienced! Six weeks have passed since we left Osh. Rahmet said that we have passed the most difficult stretch of the journey. ...The Ak-Suu valley with its monotonous depressing landscape was left behind,” the author reports. Two brave Kyrgyz horsemen, Sydyk and Abdurassul, accompanied the travelers up to the Pamir village of Langar, located almost on the border with India. There, on May 3, the expedition members bid farewell to these loyal helpers, “gave them millet and flour for the road, offered sabers, but they refused, simply taking sticks. ... Honest, selfless, brave, these people had been with us for more than two months,” continues G. Bonvalot and adds: “Later I learned that on the way home our faithful guides were stopped by Chinese Kyrgyz, who took everything they had with them. And only at the end of July did they, thank God, reach Fergana alive and unharmed.”

The expedition's crossing of the most dangerous section of the route practically refuted the previously held belief about the impassability of Pamir in winter. On August 11, the participants of the trip were already in Kashmir.

Thus, the expedition came to an end. The participants of this unprecedented crossing for those times became pioneers in studying certain aspects of the nature and ecology of Pamir. They were the first to conduct regular meteorological observations there for two months in winter conditions. Capu, describing the health condition of the local inhabitants, essentially published one of the first historical essays on high-altitude medicine. According to Stroilov, “...the described expedition is not just an interesting and instructive example, demonstrating the fruitfulness of international cooperation in studying Pamir. But it is also an event that, along with others described by French researchers about Central Asia in the last century, lies at the origins of that fruitful tradition of French Oriental studies that continues to thrive even today.”

Three years later, the initiator of the expedition awaited other equally exciting adventures: this researcher of Asia in 1889 became one of the first Europeans to visit Tibet. Subsequently, he would write many books.

For example, “In Central Asia; from Moscow to Bactria” (1884), “From the Caucasus to India through Pamir” (1888),

“Unknown Asia; through Tibet” (1896), and others. Here are some of his works that, unfortunately, are still waiting to be translated into Russian: “En Asie Centrale, de Moscou en Bactriane” (1884); “En Asie Centrale, du Kohistan a la mer Caspienne” (1885); “Du Caucase aux Indes a travers le Pamir” (1888); “De Pans au Tonkin a travers le Tibet inconnu” (1892); “L’Asie inconnue; a travers le Tibet” (1896).

And yet, the meeting with the Alay people remained one of the brightest and most memorable episodes in his adventure-filled life...

Meetings of the Alay People with Bonvalot