The Formation and Development of Tourism in the Kyrgyz Republic

To err is human, says an ancient Latin proverb. But it is human to err in the process of cognition. And knowledge is the very cause of consciousness. Regardless of what is said about humanity, the thirst for knowledge is one of the most human traits. Chronologically, it is also true. Thus, as long as humanity has existed, so have travels. The thirst for "journeys into the unknown" is truly a passion. It is no coincidence that curiosity has been humorously termed "the lust of the mind." When this passion exists, a person is no longer in control of themselves. Columbus, Amerigo Vespucci, Afanasy Nikitin, Amundsen, Miklouho-Maclay — who today does not know these names? And if this passion coincides with a social demand, then everything is simply magnificent. Here, both God and the devil lend a hand.

It was best in ancient times. Everything in the world was clear, everything was explainable, everything was simple, everything was human. The Greeks believed that they were aware of the underworld; they not only knew about the life of Adam but felt a direct connection to the events occurring there, to their own affairs. The seasons, the life cycles of plants, the entire palette of colors and sounds of nature echoed understandable familial relationships — son-in-law, mother, daughter. If, for example, it is late spring, then Pluto is keeping his wife Persephone at home. Her mother, Gaia, is in sorrow, which manifests as dampness. As we see, everything is very human. Although naive for us wise ones, it is quite charming.

Having stepped onto the first rung of knowledge, a person felt emptiness, cold, anxiety. And the ancient, myth-making line in the cognition of the world does not break. Even if a legend lacks a real basis, it does not leave the imagination indifferent. A legend is always a means of understanding the world, even if it is amusing.

But alongside legends and myths, a completely objective picture of the world is constructed — from step to step, from twist to twist.

The first mentions of the lands of Central Asia, including Pamir and Tian Shan, are found in the sacred book of Zoroastrians, the "Avesta" — the very one that, according to legend, Alexander the Great burned. Trade and political ties between the countries of the East and the Mediterranean were established — and the geographical horizon of the ancient world expanded. Already with Herodotus, Strabo, Ptolemy, and the Chinese Zhang Qian and Ban Gu, there are references to the mountainous character of Kyrgyzstan, to the waters of Oxus and Jaxartes — as the ancients called the Amu Darya and Syr Darya, respectively, to the Filled Lake — now Issyk-Kul, and to the population of those places. It can be considered that the beginning of the description was laid in the first millennium BC and at the beginning of our era.

In the Middle Ages, the description of the Central Asian lands became more detailed and reliable. Central Asia, becoming the arena of political events, attracted ambassadors, merchants, and travelers from various countries to the capitals of ancient Turkic states — Suya, Balasagun, Uzgen. Descriptions of ancient cities, distances, and roads between cities were no longer so rare.

A new twist in history for a long time interrupted the more detailed description of the territory of Kyrgyzstan. Fierce internecine wars among Mongolian, Dzungarian, and Mongolian rulers made the situation unstable. And in war, as in war. Here, rather, a heroic tale will be born than a geographical description. Thus, from the 13th to the 17th century, only the Lao monk Chan Chun provided a description of the mountains and changing landscapes in Northern Tian Shan, and the Central Asian historian Babur described Fergana, while Haidar described Semirechye and Lake Issyk-Kul.

In the 18th century, the situation began to change. Interest in Central Asia grew from Russia. Among the researchers of this time were Russian captain I.S. Unkovsky and Swedish prisoner officer I.G. Repat, who left behind maps of the region. French Jesuit-astronomer A. Hallerstein determined the coordinates of the mouth of the Ak-Terek River at Issyk-Kul and the city of Osh.

The first half of the 19th century is marked by the expeditions of A.L. Bubenov in 1818 and 1827, F.K. Zibberstein in 1825, and others.

From the darkness of ignorance, the outlines of new worlds and the faces of unfamiliar peoples became clearer, although in aggregate, all this was fragmented, sporadic information that did not provide a complete picture of the nature, culture, economy, population, and history of the region.

Separate attempts at systematization were made by European scholars, particularly Alexander Humboldt in 1843. In his monumental work, Humboldt, who had never been to Tian Shan and had only researched Central Asia, expressed a version about the volcanic origin of the mountains of Central Asia. This moment from the entire activity of the scholar is most often mentioned: Humboldt was mistaken. But he had not been there. Hence, he was mistaken. Moreover, in his version. Yet they say that respect for the history of one's own country begins with respect for the history of others. It may not have been worth discussing one of the scholars in such detail, especially one who simply expressed a hypothesis about the origin of the Tian Shan mountains, if it were not mentioned in almost every textbook, manual, and encyclopedia: later researchers of Central Asia disproved A. Humboldt's theory. Let us not forget: the later ones saw clearly because they stood on the shoulders of giants. Even if they were mistaken.

The picture changed completely in the second half of the nineteenth century when Kyrgyzstan was annexed to Russia. But this period deserves special discussion.

Read also:

Proverbs, Beliefs, and Taboos of the Nomadic Cuisine of the Kyrgyz

The word is the soul of the people! Each proverb is a true gem, extracted from the depths of the...

The Word in the Traditional Type of Consciousness of the Kyrgyz

Traditional Type of Consciousness of the Kyrgyz In the traditional type of consciousness, the...

The Evolution of Consciousness - Part of the Overall Process of Historical Development of the Kyrgyz

The evolution of consciousness - part of the overall process of historical development of humanity...

Mythological Type of Consciousness in the Development of the Kyrgyz

Mythological Type of Consciousness A person controls their own actions, accepts and bears full...

Botanical Knowledge of the Kyrgyz

Plants are the primary source of life on Earth. Using solar energy, water, and carbon dioxide,...

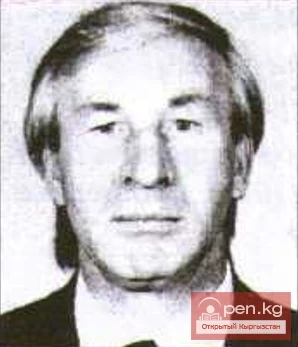

Aleksey Ivanovich Tishin

Tishin Alexey Ivanovich (1944), Doctor of Philosophy (1997), Professor (2000), Russian. Born in...

Knowledge of the Features of the Psychology of the Kyrgyz People

Peculiarities of the Psychology of the Kyrgyz People One can find the key to explaining many...

Knowledge in the Field of Practical Chemistry

In folk medicine, compounds of mercury have long been used: sulaim (HgCl2), calomel (Hg2Cl2),...

Three Degrees of Mountain Sickness. Part - 3

Mild Degree A person complains of headache, nausea or vomiting, insomnia, dizziness. The symptoms...

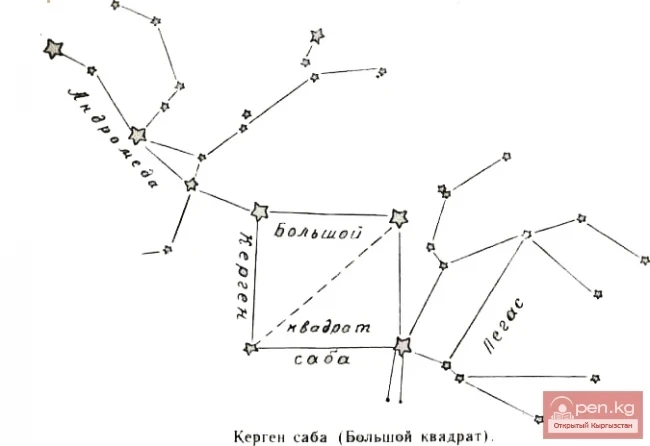

Astronomical Knowledge of the Ancient Kyrgyz

The first representations of people about nature were formed in deep antiquity. As the founders of...

Pre-scientific Representations of the Kyrgyz about Nature

Knowledge and understanding of natural processes in which human life takes place is a prerequisite...

What is the most important thing for a Kyrgyz?

Men and Women An elder was asked: "Who are more numerous - men or women?" - Of course,...

Man and Nature in Oral Folk Art

The relationship of humans to nature, animals, and plants is determined not only by their natural...

Elders

Men's Word Once, an elderly townsman accidentally met a traveler who found himself in their...

Rajal and Kaiyr

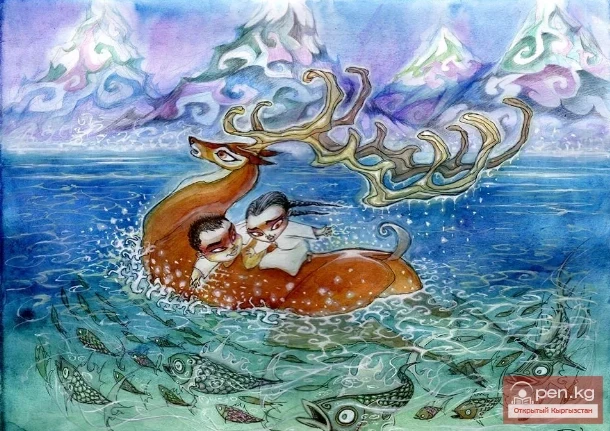

Among the Kyrgyz, there is a preserved legend-myth. In those distant times, when the world was...

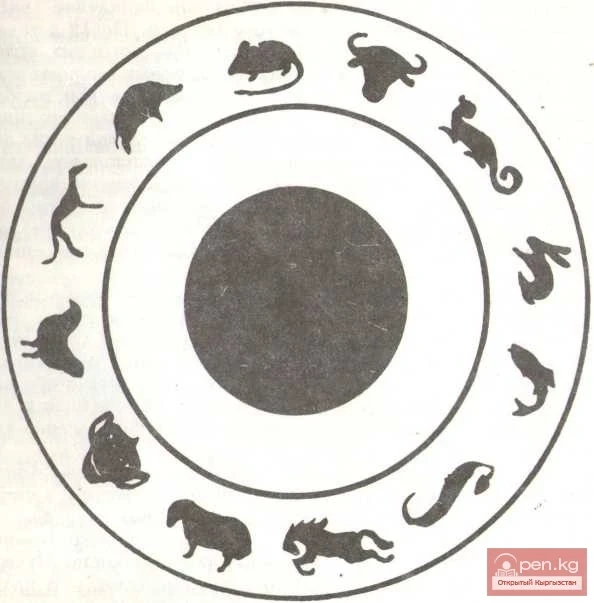

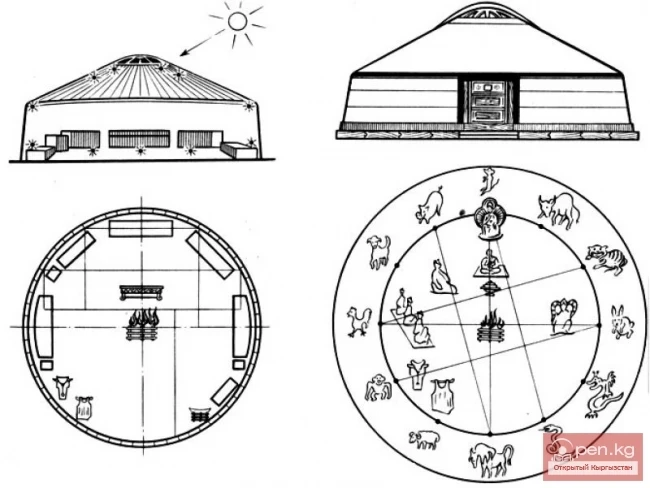

Chronology among the Kyrgyz

Kyrgyz Calendar with a 12-Year Cycle Among the Kyrgyz (as well as many other peoples), a 12-year...

What Does the Homeland Begin With?

Moyt-ake and Sart-ake Once upon a time, two renowned orators, two rivals - Moyt-ake and Sart-ake -...

At the Exhibition of Contemporary Art, Kyrgyz People Were Presented in a New Light

Recently, in the loft "Tsех," six artists working in different genres of contemporary...

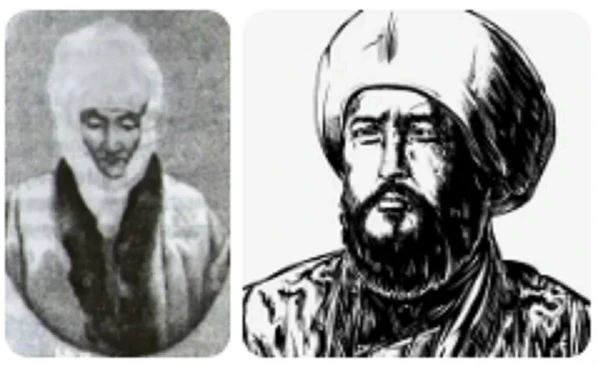

The Attitude Towards Kurmanjan Datka and Shabdan-Baatyr in Central Asia and Beyond

According to legends, Kurmandzhan Datka and Shabdan-Baatyr often showed mercy towards the poor and...

Kyrgyz Calendar

The Basis of the Ancient Calendar. Even ancient hunters, observing the change of seasons and...

How much gold does Kyrgyzstan have?

How much is the som backed by gold and currency? Almost every country has gold and foreign...

Museum of Kozhomkul

Hero Kaba Uulu Kozhomkul: What Do We Know About Him? Hero Kaba Uulu Kozhomkul was born in 1888. He...

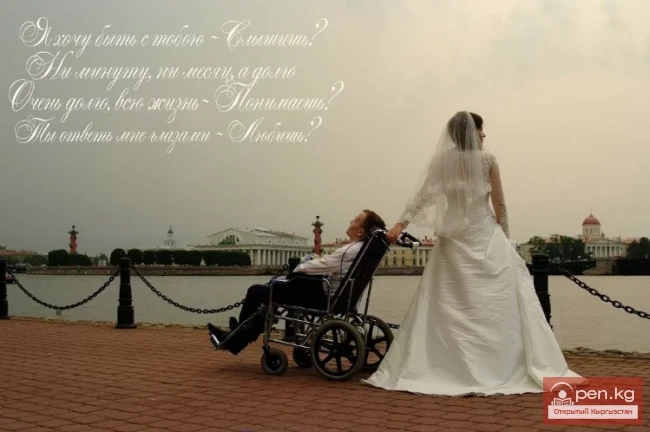

Everyone Has Their Own Happiness

Everyone has their own happiness We cannot say what a person needs for happiness. But each of us...

Love your homeland in any weather

How to Achieve Prosperity? In difficult times, a young man decided to help his people. To do this,...

Wishes from Santa Claus

Each of us tries to make the New Year celebration unforgettable and to bring a miracle to our loved...

Transition from One Historical Type of Consciousness to Another in Kyrgyz Society

Class Societies by Social Structure Each type of consciousness, until a certain point, of course,...

Seven Phenomena of Happiness

Seven Phenomena of Happiness! Long ago, in a distant mountain village, there lived a sage. For his...

"Ulburchok" - the oldest national dish

In traditional cuisine, there were dishes with meaning, that is, speaking dishes. “Ulburchok” is...

Great Lent

49 Days of Great Lent From March 15, Orthodox Christians around the world will begin Great Lent....

The Religion of the Kyrgyz in the VI—XVIII Centuries

Alongside Islam, the life of the Kyrgyz was widely influenced by customs and traditions of...

A Few Safety Tips for Tourists

Take Care of Yourself While Traveling During your travels, it is important to keep personal safety...

The Concept of Time Among the Kyrgyz

In ancient times, the functions of a compass and a clock were performed by the Sun, the Moon,...

Kochkor

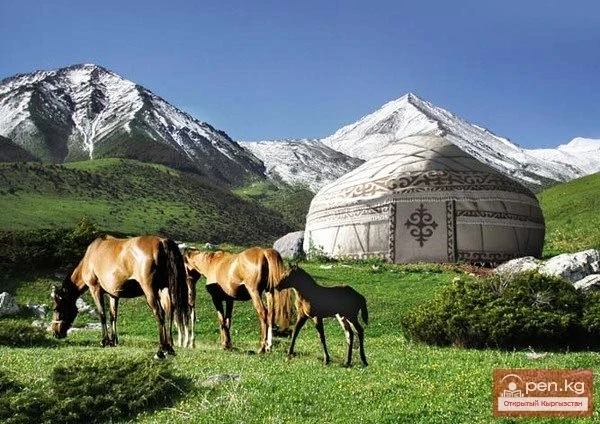

The city of Kochkor is located on the main road leading from Balakchi to Naryn and has become a...

The Legend of the Mother Deer. Continuation

Miraculous Rescue It is said for a reason — an orphan has seven fates. The night passed safely....

Life is a Journey

Since childhood, I have loved traveling. I was born in Aravan - a picturesque village in the south...

Unexpected Ways to Protect Against Mosquitoes

18 Unexpected Life Hacks Against Mosquitoes Most likely, mosquitoes were invented for the sake of...

The Formation of Abdikerim's Personality

Master of Political Game Baitik, Uzbek, and Abdikerim were destined to become masters of the...

Traveling with Children

What to Take on Vacation with a Child? Sooner or later, the time comes when you decide to take a...

Styles of Bicycle Tourism

Sportive Bicycle Tourism. This type of tourism on bicycles was invented back in Soviet times. At...

The Legend of the Lake "Kokuy-Kul"

"Kokuy-Kul" Among the high mountains lies a small but very deep lake called Kokuy-Kul....

The Legend of Issyk-Kul

How Lake Issyk-Kul Came to Be Many legends have been woven by the people about how Lake Issyk-Kul...

Polygamy

One of the major surahs of the Quran (the 4th surah, consisting of 175 verses) is called...

Education as a Means of Combating Early Marriages

For economic or social reasons, the number of early marriages in Kyrgyzstan remains high....

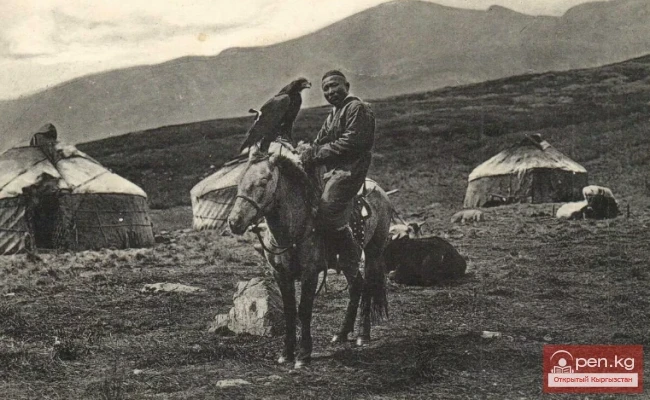

Horses for Hunting

All horses in the mountains of Kyrgyzstan are small but extremely resilient. Many refer to them as...

The Celebration Man Yegor Panshin!

Each of us has our own idea of a holiday. For some, a celebration must be associated with luxury,...

Three Epochs

Three Epochs When society goes through a transitional period, it is painful for everyone. Not...

Religion in Kyrgyzstan

Pilgrimage is the oldest form of travel, known for over a millennium. Up to 80% of tourist...