Mirror of Alienation: What the Hikikomori Phenomenon Says About the Modern World

Recently, anthropologist and philosopher Alain Julian visited a rehabilitation center for modern recluses in Japan.

In the early 1990s, Japan faced economic stagnation known as the "lost decade." During this period, many cases emerged where people began to isolate themselves in their homes, ceasing participation in work, educational, and social life. These individuals, known as "hikikomori," derived their name from the Japanese words hiku (to pull) and komoru (to seclude), implying "those who have gone inside." Initially, it was believed that this phenomenon primarily affected youth, especially men living under parental care, most often from their mothers. However, over time, hikikomori began to affect people of all ages and genders.

Today, about 1.5 million Japanese, which is over 1% of the country's population, can be classified as hikikomori. This phenomenon is also observed in other countries such as South Korea, Italy, Spain, China, France, Argentina, and the USA. Despite its widespread occurrence, there is no consensus on what hikikomori is and what causes it. This uncertainty makes the treatment process quite complex.

Some psychologists view hikikomori as a condition rather than a syndrome, linking it to various mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, or social phobia. In some cases, it has been proposed to include hikikomori in psychiatric classifications to create a new diagnosis. The mass media often portray hikikomori as immature individuals who avoid responsibility and socialization, attributing their reclusiveness to laziness or lack of skills. An example is the manga and anime NHK ni Yōkoso! ("Welcome to NHK!"), where a character obsessed with anime and games only changes after financial support from parents ceases. In the late 1990s, sociologist Yamada Masahiro introduced the term "parasaito shinguru," referring to selfish adults living with their parents.

Despite various emphases, most interpretations of hikikomori reduce it to a personal problem rooted in psychological or moral deficiencies. And although explanations diverge, they all point to the fact that isolation is an internal issue of the individual. But how justified is this assertion in the modern "age of loneliness"?

In search of answers, I traveled to Japan to visit one of the many rehabilitation centers for hikikomori that have emerged in the country over the past decades. These institutions offer informational support and psychological assistance. As a researcher, I wanted to find out what "rehabilitation" actually means and how one can treat a condition that lacks an official diagnosis.

On a cold winter morning in 2024, I arrived at a train station in central Japan, where I was met by Fumiko, a woman just over thirty years old, who works at the rehabilitation center for hikikomori. A few months earlier, the center's director had granted me permission to observe their rehabilitation program, which they refer to as "school."

The center is located in a building on the outskirts of the city, surrounded by suburban houses and agricultural land.

Inside, I met seven staff members, after which Fumiko led me to the "class." Upon opening the door, I saw a young man partially hidden under a mask and a large jacket, standing in front of a board. At tables spaced a meter apart, several people were seated, turning to look at us.

These were hikikomori attending treatment, including both teenagers and individuals just over thirty. I briefly introduced myself and took a seat at the back.

For ten days, I immersed myself in the life of the center, where the daily routine was clearly structured. We were awakened at 7:30 AM, breakfast was at 8:30, and classes began at 9:30, announced by a school bell. The bell also signaled the start and end of lunch, and the school day concluded at 4:00 PM. Residents prepared their own meals and cleaned up. The only deviations from the routine were physical education classes on Wednesdays and rare excursions, such as to a nearby farm.

The dormitory included a small living room with a television, a kitchen, and a corridor leading to the women's rooms. On the second floor were small men's rooms without windows, where temperatures sometimes dropped below zero in winter.

During my conversations with the residents of the center, I heard many different stories. However, there was a common thread: fear, trauma, or stress had led to isolation, which helped restore inner balance. It was a way to find safety. Nevertheless, explaining the duration of this isolation proved much more difficult. My interlocutors fell silent, their gazes becoming vacant as if they were searching for an answer that eluded them.

Contrary to the common perception of hikikomori as people avoiding responsibility, most sincerely desire change. Many describe their state as being stuck, where each day is a struggle. They feel guilty for not meeting the expectations of their relatives and society. I noticed that they appeared tired and sad, hoping that the rehabilitation center would help them start a new life. How exactly does the center assist in this process?

Classes at the center include arts and crafts, acting, and public speaking. However, in practice, they seem to occupy the residents more than teach them anything. Often, classes were conducted in an improvisational format, without a clear structure. To better understand the program, I spoke with the founder of the center, who briefly outlined its essence: "When people cannot follow rules, they become hikikomori. We teach them the rules so they can adapt to life, especially in work."

The main idea is that social integration depends not on mutual understanding but on adherence to rules. This reflects a broader cultural tradition in Japan, where mental difficulties are often perceived as trials to be overcome. Well-being is associated with perseverance and the ability to accept fate. This approach remains popular, especially regarding hikikomori, who are often considered lazy or weak. As the founder noted: "I strive to make my students emotionally resilient so they can recover from failures."

The goal of the classes is to instill essential life qualities such as discipline and independence. This spirit permeates the everyday life of the center. Residents are expected to demonstrate independence, and they are strongly discouraged from helping each other with simple tasks. Even minor support, like assistance with laundry or dishwashing, is not welcomed. This way, the ideal of individual responsibility is formed.

The rooms in the dormitory also became part of the learning process. They are intentionally designed without amenities. When I complained to Fumiko about the cold in my room, she replied without hesitation that it was done intentionally to draw residents out of isolation into warmer common areas.

I concluded that care does not imply comfort or warmth but demands submission. Here, the "self" became an object of correction rather than understanding.

Since hikikomori does not have an official diagnosis, there is no single definition of recovery. This leads rehabilitation centers to develop their own therapy rules, often based on parental expectations. In this center, progress is measured by the degree of independence and personal responsibility. Some patients may spend months or even years in low-skilled jobs in factories, farms, or postal services. But the question of whether they can escape the forces that initially led to their isolation remains open.

One former resident of the center, Miyuki, a woman just over thirty who found part-time work, told me about her life with two "personalities." On the outside, she has returned to normal life, works, and follows a routine. But she has not "recovered": she lives with another version of herself — hikikomori. "I realize that I am both at the same time," she said. "Even now during the holidays, I often stay home. I have no friends or family. So I still feel a bit hikikomori."

"Recovery" through gaining independence did not lead to the cessation of her social isolation. Although work helped her shed the label of "hikikomori," the deeper problem remained. For people like Miyuki, one form of isolation can be replaced by another. This highlights a more serious issue underlying the hikikomori phenomenon.

Today, nearly 40% of Japanese households consist of one person. Even among working citizens, labor market flexibility has led to traditional working relationships, once called "shokuba kazoku" (working families), becoming rare. And this problem is not limited to Japan alone. People worldwide are becoming socially isolated. Thus, hikikomori embodies social failures, marking individuals unable to adapt, work, or participate in a productive society. Rehabilitation may make them independent and employed, but it does not always restore a sense of belonging.

We live in a world of virtual connections, unstable employment, and community disintegration. Hikikomori reveal the social logic of change: participation in life is only possible in the context of productivity. They are not just outcasts; they reflect values that many share in an era of burnout and loneliness. Thus, Japanese hikikomori, once perceived as an anomaly, now act as mirrors reflecting a common sense of alienation experienced by many, regardless of employment status.

Source

Read also:

A Japanese Man Sang in Kyrgyz and Made a Music Video in Anime Style

The video was created by students from a Japanese special school, and the author of the Kyrgyz text...

Interesting Facts About the Earth's Population

The Earth's Population This is the total number of people living on our planet. As of today,...

On Sanjyr during the Years of Perestroika and Sovereignty

The glasnost of the perestroika period opened new opportunities for the study and popularization...

The Main Snow Maiden of the Country

“Tell me, Snow Maiden, where have you been? Tell me, dear, how are you?” - each of the modern Lady...

A Employment Center for Migrants to Open in Southern Kyrgyzstan

In the southern capital of Kyrgyzstan, a Center for Employment for domestic migrants abroad will...

The Employment Center sent another group of Kyrgyzstani citizens to work in Korea

Recently, the Center for Employment of Citizens Abroad sent a new group of Kyrgyzstani citizens to...

The title translates to "The Entertaining Planet."

The clearest water is found in the Sargasso Sea (Atlantic Ocean). There are over 1300 types of...

Post-Soviet Countries and the Middle East Among World Leaders in Anxiety and Anger — Gallup

According to Gallup, in 2024, the level of anxiety among the adult population reached record...

Kyrgyzstan Youth Meets Their Idols

Former President of Kyrgyzstan Roza Otunbayeva, cosmonaut and hero of Kyrgyzstan and Russia...

Nauryz (New Year)

On the day of the meeting of the Jaz Mayram — the spring holiday, people usually dressed...

The Central Election Commission of the Kyrgyz Republic has posted the addresses of overseas polling stations on the map.

The Central Election Commission of the Kyrgyz Republic, as reported by the press service, has...

Kyrgyzstan in the Years of Perestroika

A Turn in Social and Political Life. By the mid-1980s, a deep crisis had emerged in all spheres of...

Neural Networks Are Changing How We Think and Speak: Scientists' Conclusions

Similar changes may also occur in the field of language. Psychologist Lev Vygotsky emphasized in...

Who Lives and Works at the Bishkek Landfill?

The city landfill on the outskirts of Bishkek, which has been operating since the 1970s, has been...

Non-communicable diseases cost the economy of the Kyrgyz Republic nearly 30 billion soms

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) inflict an economic loss of 29.8 billion soms on the economy of...

Atambayev: "We have reached 6 million, and the population growth of Kyrgyzstan reflects people's confidence in the future of their country."

President of the Kyrgyz Republic Almazbek Atambaev met today, November 26, with the Prime Minister...

Grandmother from Kyrgyzstan Featured on the Cover of the International Report on the Rights of Older People "We Have the Same Rights"

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan - Older women from around the world speak about human rights in a new report...

Geoecological condition of the land

Currently, in the Chui Valley, with the formation of numerous small farms, peasant and other...

Where, how, and what kind of assistance can victims of domestic violence receive in Kyrgyzstan?

Every year, hundreds of cases of domestic violence occur in Kyrgyzstan. Headlines like...

Kyrgyz Diaspora in Turkey

Kyrgyz in Turkey. In the village of Uluu Pamir in the Turkish province of Van, about 800 people...

President of the Kyrgyz Republic Almazbek Atambayev awarded presidential scholarships to outstanding students of the country's universities.

President Almazbek Atambayev: “The pursuit of knowledge is the key to success in the modern...

Apas Dzhumagulov on Kyrgyz Women

Apas Jumagulov on Kyrgyz Women The history of the development of world civilization is largely the...

Types of Kyrgyz Family

The predominant type of family at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century was the...

The world's first solar helioconcentrator with two towers launched in China

This solar power plant was created by China Three Gorges Corporation, known for constructing the...

Migration Situation in the Kyrgyz Republic from 1991 to 2005

According to various estimates, between 500,000 and 800,000 people have left Kyrgyzstan since...

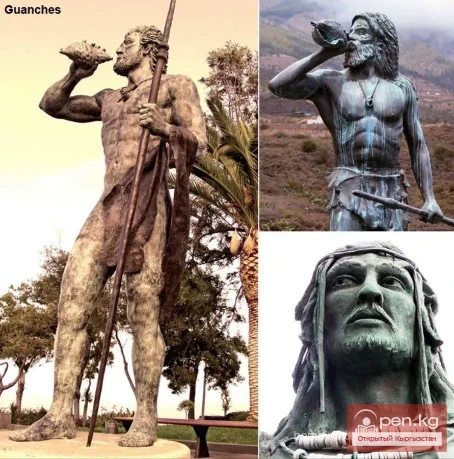

Guanches. The Mystery of the Disappeared Tribe of the Canary Islands

Guanches - Who Are They? The mystery of the small but very freedom-loving and courageous tribe of...

The Origin of the Names of the Countries of the World. K-K

Kazakhstan. “Land of the Kazakhs.” From the name of the people, which, according to one version,...

Kyrgyzstan Joins Regional Efforts to End Violence Against Children

From October 13 to 14, representatives of Kyrgyzstan participated in a two-day ministerial...

The Good and the Burden of Foreseeing

The Good Sometimes we do not understand people simply because we view the world from our own...

"Hidden Pandemic": New Report on Sexual Violence Against Children in Europe

Children's organizations report that 5 million children in Europe face sexual violence every...

Population of Kyrgyzstan as of January 1, 2013

Population of Kyrgyzstan Thanks to the fundamental changes that occurred in Kyrgyzstan after the...

Population of the Kirghiz SSR from 1959 to 1991

Census of the Kyrgyz SSR in 1959 - 1970 - 1979 - 1989. According to the 1959 census, the...

Fox - Tulkу

Fox— Vulpes vulpes Linn (in Kyrgyz: tulku) In Kyrgyzstan, it is widespread, from areas cultivated...

Wolves - Karyshkyr

Wolf — Canis lupus L. Widely distributed throughout Kyrgyzstan, from its valley regions to high...

Recording and Collection of Genealogical Traditions of the Kyrgyz

In the mid-19th century, some influential manaps, realizing the significance of the sanjyr, began...

50 Interesting Facts About India

50 interesting facts about India that you might not know: 1. India is the most multilingual...

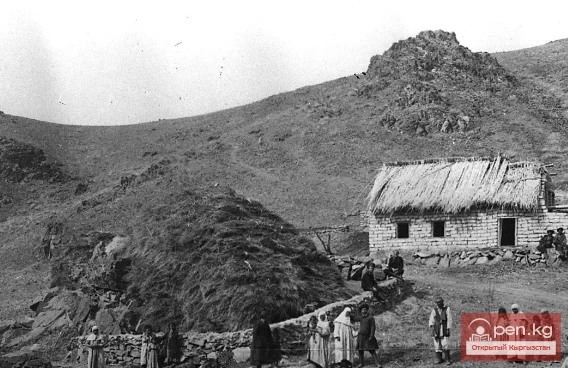

The 19th Century — A Century of Radical Change in the Lives of the Kyrgyz

Settlements and Permanent Housing The 19th century was a turning point in the life of the Kyrgyz....

Weaving

Among other domestic crafts, weaving held one of the primary places among the Kyrgyz in the past....

Kyrgyz Women Received Dance Gifts on International Women's Day

A video has been circulating in Kyrgyz social networks, posted by OJSC "Bishkekteploset"...

The construction of the National Center for Traumatology and Orthopedics continues

In Bishkek, the construction of the National Center for Traumatology and Orthopedics is actively...

Three Epochs

Three Epochs When society goes through a transitional period, it is painful for everyone. Not...

Peak Free Korea

Peak Free Korea - located on the Ak-Sai ridge within the Ala-Archa National Park. In the past, one...

In the city of Manas, more than thirty protocols were drawn up against parents during a nighttime raid.

In Manas, as part of the operation "Teen-Night," law enforcement officers drew up 32...

Preparation for Hunting in Kyrgyzstan

Preparation for hunting in Kyrgyzstan is a topic that deserves special attention. The thing is...

From the USA to the Vatican. Investigative Journalists Uncover Another Celebrity Surveillance System

The scandal involving NSO Group and its spyware Pegasus has not yet subsided when journalists...

Polygamy

One of the major surahs of the Quran (the 4th surah, consisting of 175 verses) is called...