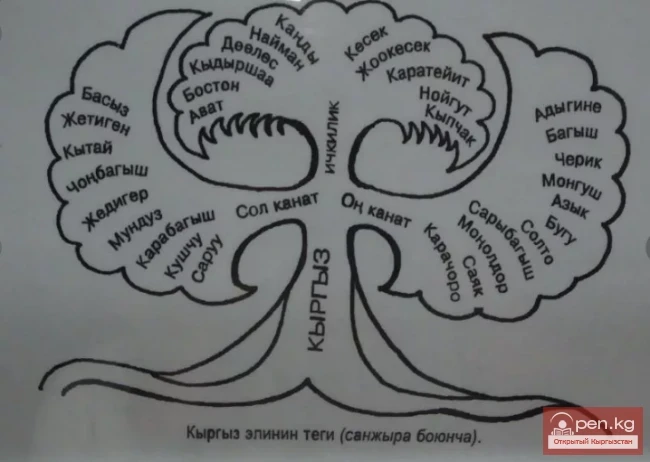

Under the ethnonym "Kyrgyz," the Tian Shan Kyrgyz are referred to, who are now part of the Kyrgyz Republic, and not the Yenisei Kyrgyz.

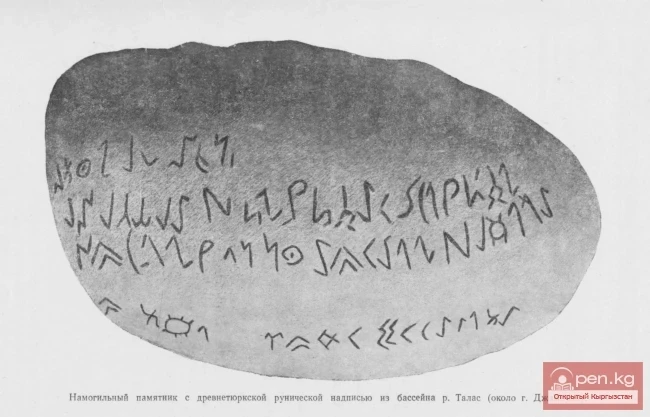

It is believed that the Kyrgyz did not have a literary language or writing during the pre-national period.

So far, this opinion has not been scientifically confirmed or refuted by anyone. There are separate statements regarding this matter.

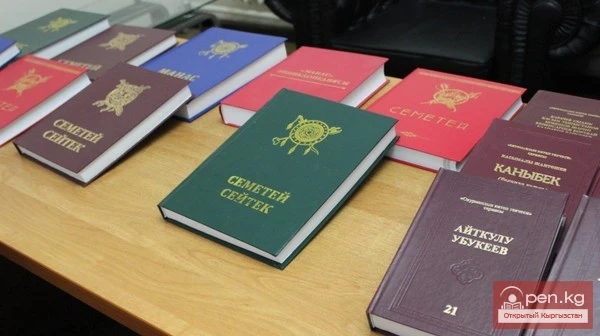

Regarding the culture of the Kyrgyz people, A. Kanimetov wrote in 1962 that the oral creativity of the Kyrgyz includes over ten thousand epic works; since there was no writing, it reflected all significant events, all movements of life and public thought, and furthermore, no book or newspaper was published in the Kyrgyz language before the revolution, leaving the people completely illiterate.

Describing the state of the culture of the Kyrgyz people before the October Revolution, S. S. Daniyarov asserted the same — in the pre-revolutionary period, the spiritual culture of the Kyrgyz people, who had no writing, and therefore no printed literature, was dominated by oral-poetic creativity, which was remarkably rich in genre and form. Nevertheless, S. S. Daniyarov noted the first handwritten works that appeared in Kyrgyzstan at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, belonging to akyns-writers: the number of these works was very insignificant.

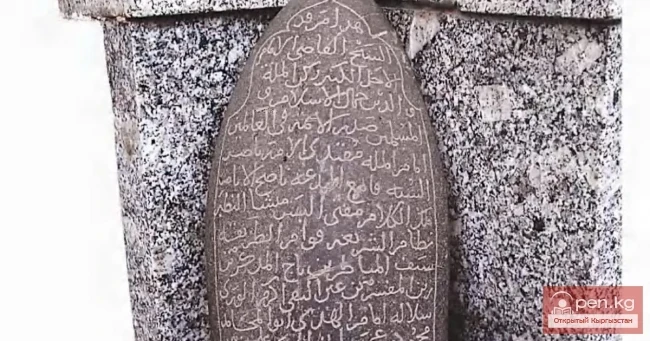

Regarding Kyrgyz writing, S. S. Daniyarov spoke categorically. He writes - however, in the works of some local scholars, unfounded claims sometimes appear that the Kyrgyz allegedly had their own national writing even before the establishment of Soviet power; it is necessary to distinguish between two concepts: writing and written language; before the October Revolution, the peoples of Central Asia, Kazakhstan, and some Turkic ethnicities adapted the Arabic alphabet to their languages to varying degrees, but it did not reflect the lexical, phonetic, and other peculiarities of the languages of these peoples; Arabic script was mainly used by representatives of the Muslim clergy, and it was inaccessible to the broad working masses. In an interview with the journal "Soviet Turkology," Ch. T. Aitmatov also doubted the existence of written culture among the Kyrgyz in the recent past. Scholars of Turkology have differing opinions. Here is what I. A. Batmanov wrote in 1957 — the Kyrgyz used letter writing before the October Revolution, had writing, but such that did not reflect the essential features of their language. In a similar vein, K. K. Yudakhin wrote in 1965 in the preface to the Kyrgyz-Russian dictionary — before the October Revolution, literate Kyrgyz (and there were few) used an Arabic alphabet that was poorly adapted to the Kyrgyz language and wrote by imitating the samples of the so-called Chagatai (Old Uzbek) language. This point of view was also held by S. E. Malov. Those who studied the language of Kyrgyz official documents, V. M. Ploskikh and S. K. Kudaybergenov noted in 1968 that — before the revolution, the Kyrgyz, like many other Turkic peoples of Central Asia, wrote their few documents and genealogies using the Arabic alphabet, in the so-called Old Uzbek (Chagatai) language.

Examining the historical aspect of Kyrgyz orthography, X. K. Karasaev expressed his opinion in 1970 — the Kyrgyz people, starting from the era of using Arabic letters, and until the October Revolution, left manuscripts of official documents and literary works, as well as several printed books - this has been known for a long time. The conclusion of E. A. Abduldaev states that the Kyrgyz language received its initial literary form mainly in various genres of oral folk creativity, — and not a word about written literature in the 17th century.

Thus, researchers of the culture of the Kyrgyz people have expressed themselves in favor of the absence of old writing among the Kyrgyz, while Turkologists have almost unanimously supported its recognition. However, since Turkologists-linguists did not provide a detailed argumentation in favor of Kyrgyz writing, the opinion that the Kyrgyz had neither writing nor a literary language has become established.

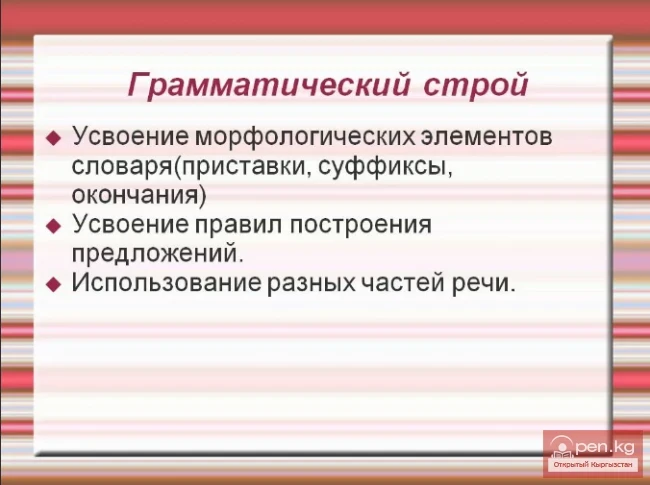

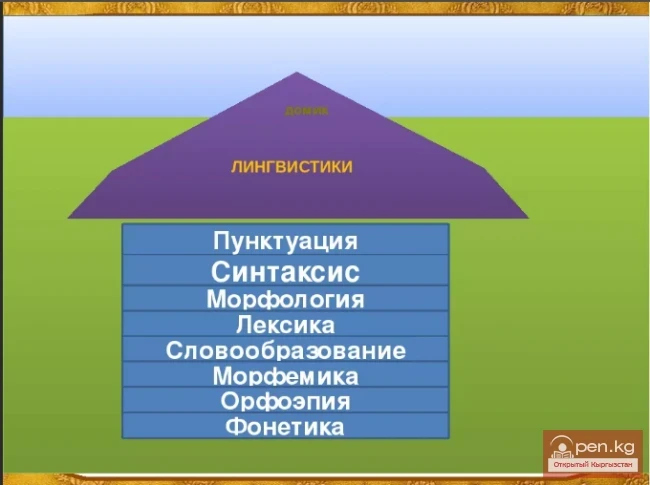

I believe that there are now grounds to disagree with such a statement. Academician V. V. Vinogradov rightly wrote that the study of the literary language is closely connected with the study of literature — in the broadest sense of the word; the study of literary language is inseparable from the general history of the language and literature of the respective peoples, since we encounter literary language — in one understanding of this term or another — primarily in the history of language and literature; thus, the study of literary language is also linked to the cultural history of this people, since phenomena associated with literary language, such as writing, literature, and science, fall within the orbit of cultural history; at the same time, literary language is one of the most real tools of enlightenment, which means that the study of literary language intersects with the tasks of education and schooling.

In other words, studying literary language in history or in its modern state inevitably involves literature, culture, history, and the education of the people.

The very existence of a literary language can only be confirmed by texts: if there are texts, there is a literary language; if there are no texts, there is no literary language; only the entire collection of texts gives an idea of the genre and stylistic variability, of the richness of the literary language. This position should not seem categorical — after all, we are talking about the book-writing modification of the literary language.

Did such texts exist among the Kyrgyz in the past?

The answer must be affirmative: yes, such texts did exist among the Kyrgyz, and they can be used to judge the literary language. First of all, these are printed texts. Among them is the poem by Moldokylych Shamyrykanov (Töregeldin) titled “Kıssa-i Zilzala” (The Tale of the Earthquake), prepared for publication in Ufa at the "Medrese and Galiya" and published in 1911 in Kazan. Two more publications — two stories — were prepared by Osmonaly Sydykov: in 1913, the book “Mukhtasar Tarikh Kyrghizie” (A Brief History of the Kyrgyz) was published in Ufa, and in 1914 — “Tarikh Kyrgyz Shabdan” (The History of Kyrgyz Shabdan).

Significantly more texts have survived in manuscript form. I had the opportunity to see Kyrgyz manuscripts in the early 1930s in southern Kyrgyzstan.