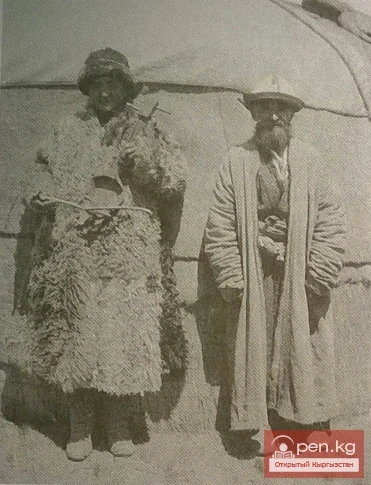

Men's Clothing of the Kyrgyz

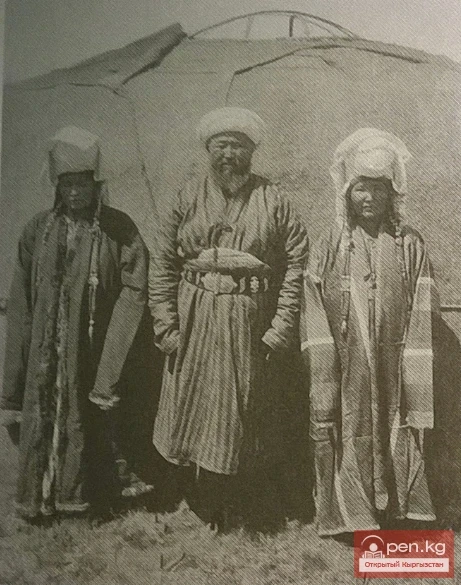

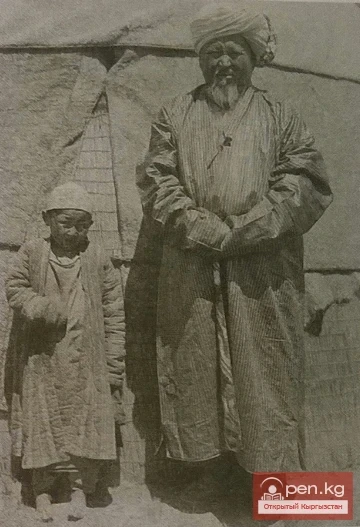

The traditional men's costume of the late 19th to early 20th century consisted of undergarments: a buttoned shirt and trousers; outerwear: waist (sharovary), shoulder: short beshemet, zhele, keltche, long robes chapan, chekmen made of hand-woven fabric - cheten, felt cloak kementai, fur coats, as well as belts, sashes, and waist scarves, headgear, and footwear.

The buttoned shirt achyk koynek, zhegde, worn from early childhood, was made of white calico or homemade fabric. It had a tunic-like cut, with the body expanding due to trapezoidal side panels. The length of the shirt was below the knees, and the sleeves covered the wrists. In the south, the shirts had a fitted collar, while in the north, a laid-down collar. The collar was fastened with braided cords or buttons. From the late 19th century, the long buttoned shirt was replaced by a short pullover shirt with a shoulder seam, a vertical collar (20-30 cm) with a placket, a standing collar, and a "button-buttonhole" fastening (in the north) or a triangular collar (in the south). The shirt was worn over the sharovary, belted with a sash.

The undergarment trousers yshtan, dambal, ylyzym were made of calico or fabric, characterized by a large diamond-shaped gusset sewn between the legs for ease of movement and sitting on the floor. The trouser legs, which reached the ankles, tapered slightly towards the bottom. The upper sharovary were made from woolen hand-woven fabric, horse, sheep, and goat skins, leather, suede, factory-made cotton and wool fabrics, and velvet. The sharovary were closed and tightened with a belt ychkyr, which was threaded through a casing from the turned-out upper edge of the trousers and tied in front. Young men's belts were often decorated with colorful embroidery and tassels. The cut of winter sharovary featured smaller gussets made of wedge-shaped pieces rounded along the stride line. The trousers made of sheepskin were significantly narrower, lacking gussets, and were sewn from pieces of various shapes, worn with the fur inside.

From the skin of a roe deer or wild goat, the Kyrgyz made fine suede, which served as material for sharovary teke shym, zhargak shym, kandagay, chalbar. They were distinguished by significant width, as when going on a long journey, travelers tucked the hems of their outer clothing into the sharovary; the wide trouser legs lay over the footwear. These trousers had no gussets, and the legs were sewn at an angle, creating an arched rounding in the stride. There were slits at the bottom of the trouser legs on the sides. Suede sharovary were embroidered with silk, with patterns placed on the lower part of the legs. This type of clothing was worn for participation in sports competitions, hunting, and festive celebrations.

A typical type of men's outer shoulder clothing was the quilted robe chapan. Three variants of such a robe can be distinguished by cut and stitching method. The oldest was tuura chapan, made from black or blue dense fabric. It featured a tunic-like cut, wide, expanding downwards due to side panels, with tapered sleeves sewn at a right angle, complemented by a diamond-shaped gusset. A wedge chalgay with particularly dense stitching was sewn to the front edges, while the rest of the tuura chapan was quilted in rows of stitches spaced 3-4 cm apart.

The second variant of chapan - chepken, kaptama chapan - was widespread in the northern regions of the country. Kaptama chapan was characterized by the presence of a shoulder seam and armholes, where the sleeve with a cut head was sewn in. This robe had a loose cut, with significantly widening hems, allowing for a deep overlap. The upper part was quilted together with a layer of cotton or wool, and the lining was sewn loosely.

The third variant of chapan was characteristic of the Kyrgyz in the lowland part of the Fergana Valley, who adopted it from their neighbors - the Uzbeks and Tajiks. This variant is referred to as "ton" in southern dialects. The Fergana men's robe was made from black satin, but young people preferred bright striped fabric bekasab. With an overall tunic-like cut, the body of the robe was straight and narrow, with a small front wedge - chalgay and side slits zhyrmach; the sleeves were also narrow. The robe featured dense stitching, and its edges were trimmed with a cord, usually green.

A traditional upper men's garment was the cheten robe made from woolen fabric produced at home. Depending on the quality of this fabric, the robe was called basma (tepme) chepken, piazi chepken. The chepken served as a kind of cloak worn over the entire outfit, including even the fur coat, so it was made wide, long, with long and wide sleeves. The cut of the chepken had two variants: with a wedge at the front hem and sleeves sewn from transverse strips, and without a wedge at the front hem, with sleeves cut according to the fabric's grain. The chepken could have a shawl collar.

Chepken made from piazi fabric was expensive and not accessible to everyone. It was festive clothing and was sold in the Central Asian market. Especially valued were chepkens made from white piazi. More affordable and most popular among shepherds was the tepme chepken. From the early 20th century, chepkens began to be sewn, maintaining the old cut, from purchased factory fabric - cloth and dense cotton fabric, often striped.

The undergarment fur coat ton (in the south - postun) was an essential part of every man's clothing, necessary in the mountain climate, especially for the nomadic groups of the Kyrgyz. Boys began to wear a small ton from the age of three. The ton for adults was cut from 6-8 sheep skins, tightly sewing the edges of the pieces with woolen threads. The cut was uniform everywhere, with a slightly slanted shoulder line, wide sleeves, and hems that widened downwards, with a deep overlap.

The old-fashioned traditional ton did not have a collar. The ton was sometimes dyed orange, and less frequently black.

The edges were usually trimmed with a strip (4-5 cm) of black fur, and sometimes a double two-colored - black and white. Along the edges of the ton, strips of black velvet or satin were sewn. In the southern regions, in addition to this, triangular pieces made of black fabric were sewn onto the shoulders, back, and the beginning of the side slits.

In the early 20th century, under the influence of Russian settlers' culture, a new cut of sheepskin fur coat became widespread on Issyk-Kul - cut at the waist, with gathering on the back and a small laid-down collar made of sheepskin. This clothing was called orus ton or buyurmё ton.

Wealthy Kyrgyz, along with the ton, had fur coats made from fox, sable, and wolf skins. A dense dark fabric was used for the covering, and the edge of the fur coat was trimmed with a strip of fur 2-3 cm wide. Depending on the type of fur, the fur coat was called kish ichik, tulku ichik, karyshkyr ichik.

A specific feature of Kyrgyz clothing was the felt garment kementai in the form of a cloak or robe, which has come from ancient times. The oldest kementai were made from a single piece of felt in its natural color; later, two equal halves were cut out, sewn together with a tight seam, and decorated with patterned stitching. The edges and collar of the kementai were trimmed with black velvet and embroidered. The felt cloak was an indispensable garment for a nomad, perfectly protecting the herdsman from cold, rain, and wind, and also serving as battle attire.

Another ancient type of men's outerwear was the daha daaky made from the skin of a foal with the fur on the outside, with the mane lying horizontally along the back. Shepherds wore the archaic chiydan - a robe made from camel felt, covered with homemade woolen fabric.

By the end of the 19th century, in men's clothing, as well as in women's, tailored clothing beshemant, kemsal, kurmё developed with a looser cut than beshemant and somewhat longer; it could have a laid-down collar. Zhelek was most often sewn from striped homemade fabrics. Tailored clothing was characterized by diversity, leading to terminological confusion: there were more than two dozen names for it, some of which were compound. In the popular consciousness, the transition to sleeveless and short outerwear was generally perceived as a negative phenomenon.

Footwear and jewelry of Kyrgyz women in the late 19th - early 20th centuries.