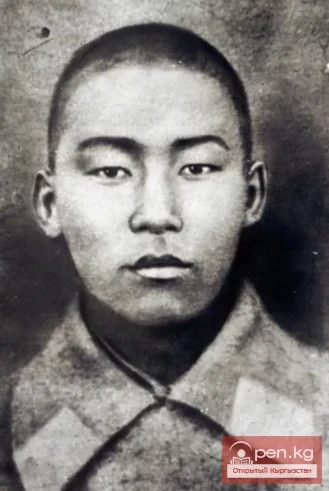

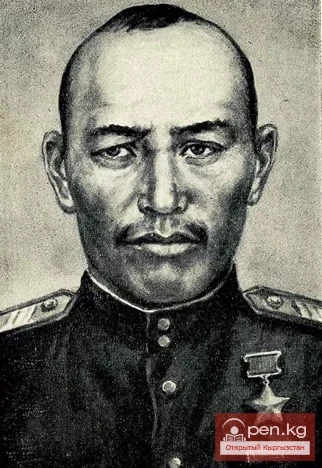

Hero of the Soviet Union Moskalenko Ivan Vasilyevich

Ivan Vasilyevich Moskalenko was born in 1912 in the village of Georgievna, Kurday District, Kazakh SSR, into a peasant family. He was Ukrainian. Having lost his father early, he worked on a collective farm, helping his mother support the family.

Before being drafted into the army, he worked for eight years as an accountant in communication departments in the Issyk-Kul region. In the early days of the Great Patriotic War, he went to the front. Private. Rifleman. The brave warrior fought valiantly near Moscow as part of the 316th Rifle Division.

In the battles near Moscow, the legendary Panfilovtsy performed an immortal heroic feat, defending the approaches to the capital in the area of the Volokolamsk highway. In the battle on November 16, 1941, during the repulsion of the attack of 50 enemy tanks at the Dubosekovo crossing, I. V. Moskalenko displayed unparalleled courage, iron endurance, and greatness of spirit. He died in unequal combat alongside other Panfilovtsy, blocking the way to Moscow.

For his displayed bravery, courage, and heroism, he was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union on July 21, 1942.

DEATH BY DEATH

It is exactly 118 kilometers from here to Moscow. The Dubosekovo crossing. Hills. Thickets. Open field.

There are many fields in Russia. But there are those that define not only the given area but also silently speak of the courage of the people, echoing the events that have forever remained in history.

Kulikov Field. Borodino. And this, at Dubosekovo. Fields of military glory, unyielding resilience of the people.

An open snowy plain. Frosty November 1941. And the trenches where the Panfilov guards await the enemy.

This is their last line of defense, for there is no retreat. Just a little further to Moscow — stand for it firmer than iron, steadfastly, irrevocably, shield the capital with your chest.

So thought the 28 Soviet soldiers. On November 16, they were still unknown to anyone. And then they entered songs and poems, into legend.

There were twenty-eight of them. But each had their own biography. Their own pre-war life, profession, family.

None of them were career military personnel and hardly dreamed of military feats. Collective farmers, workers, clerks... You read the short lines of their biographies — nothing special. Before the war, they lived in Kazakhstan, in Kyrgyzstan. And Ivan Vasilyevich Moskalenko is rightfully considered one of their own in both fraternal republics.

He was born on Kazakh soil, in the village of Georgievka, in a peasant family. When the Great October Socialist Revolution broke out, Vanya was five years old.

— Well, Ivan, — his father lifted his son into his arms — A completely different life begins. A very interesting life indeed.

But Vasily Moskalenko did not live long.

Heavy forced labor under the kulaks wore him down prematurely. Two years later, they saw Vanya off with his mother to his father's final resting place.

At seven years old, he should have been running around the village with the other boys, but his carefree childhood ended abruptly with his father's death. Now Ivan, like an adult man, would rise in the twilight and go to help his mother, who was already busy in the yard. They had a modest household — chickens, ducks, and geese, but it required a lot of care. Thus, Ivan developed a habit of daily labor.

— There he is, my man,— his mother would sometimes say and cry.

And then she was gone too. She fell ill and did not go to the doctor, thinking it would pass. But it gripped her tightly, and death did not relent. Ivan was left alone.

He then entered that youthful age when the troubles and misfortunes that beset a person are experienced relatively easily. Around him, young joyful life was bubbling, and he believed that only good lay ahead, as long as he did not succumb to gloom.

Of course, Ivan Moskalenko had his dream. Who among the boys in those thirties was not drawn to the high blue sky? The Ninth Congress of the Komsomol threw out the battle cry "Komsomolets — to the airplane!" Young men and women signed up for aeroclubs and glider schools, preparing themselves for service in the Air Force of the Red Army.

At eighteen, Ivan moved to Frunze, enrolled in accounting courses, and in the evenings began attending a glider school. And then a treacherous illness crept in — malaria. For several days, Ivan tossed in fever on a hospital bed, and when the crisis passed, the doctors delivered their verdict: he could no longer fly, his health would not allow it.

And with even greater determination, he sat down to work on the ledgers, learning to balance debits and credits. After completing the courses, the young accountant was sent south, to Karavan. There he met his future wife, Elena Fedotovna. She was studying to be an accountant, they had common interests, and they liked each other. Many took Ivan and Lena for brother and sister. Blond-haired and gray-eyed, they indeed looked very similar. But what united them was, of course, something much more important — a shared outlook on life.

— You see, Lena,— Ivan would sometimes say,— some people look at us, the accounting workers, with a kind of smirk: they’re buried in numbers and don’t even lift their heads. But I’ll tell you this: what did Lenin write? Socialism is accounting. So count whether we are needed or not.

Ivan Vasilyevich respected his profession. He was counting not someone else's money — but the people's kopecks, and this task was important, a true state affair. Sometimes the meticulousness of the accountant irritated the management.

— Oh, you paper soul,— he would hear sometimes.

But he ignored the reproaches and hurtful words. He knew one thing: he was appointed to control the economic activities of the institution, and the main thing to be guided by was order in affairs. So sometimes quarreling with the management was not such a great sin, as long as there was no harm to the state treasury.

— He has a strong character,— his colleagues would say about Ivan Vasilyevich.

Perhaps, in relation to the accounting profession, this is the highest praise.

Then they moved to the Pre-Issyk-Kul region. First to Chatkal, then to Pokrovka. There, Ivan Vasilyevich worked in the district communications office, and on weekends he often went fishing in the mornings. Together with his wife, he loved to climb the nearby hills, from where the entire width of the wonderful lake could be seen. It was calm and quiet around. Their life flowed similarly, seemingly without any special events. But when their firstborn, Gennady, was born, Ivan Vasilyevich organized a real celebration at home. They sang and danced and made good toasts. Someone from their acquaintances brought a gramophone with records.

One song stirred his soul. It seemed to remind him that the world was restless and that ominous times were approaching.

If tomorrow is war, if the enemy attacks,

If dark forces invade,—

As one man, the entire Soviet people

Will rise for the free Motherland.

The year 1941 came. On a warm and long June Sunday, they heard on the radio — war! Here, on the shores of Issyk-Kul, everything still breathed peace, while there, on the western borders, blood was already being shed and border guards were dying, fighting against superior forces of the fascist hordes.

He was drafted on July 12. Ivan Vasilyevich hugged his wife, kissed his son. The whole village came out to see off the mobilized.

He did not say to Elena: "Goodbye!" He did not think of death. When the vehicles moved beyond the outskirts, he shouted: "See you!"

That’s how she remembered him — confident in himself.

Only four letters sent by Ivan Vasilyevich have survived. "Genochka, son, I see you in my dreams every day. Grow big, when we meet — I will tell you what war is like." And to his wife, he said only one line from the last soldier's triangle: "I smoke and am turning gray."

That was all. He did not like long words, he was used to expressing himself briefly.

Their 316th Rifle Division, commanded by Major General Ivan Vasilyevich Panfilov, took up defense in the Volokolamsk direction and entered battle on October 14.

The enemy was rushing to the capital. Hitler's generals were already cherishing hopes of holding a festive parade in defeated Moscow. But they did not account for the courage and tenacity with which Soviet soldiers defended Moscow. On November 5, the newspaper "Izvestia" wrote: "The fighters under Commander Panfilov are truly fighting heroically. With a clear numerical disadvantage, during the most brutal of their attacks, the enemy was able to advance only one and a half to two kilometers a day. These two kilometers came at a very high price."

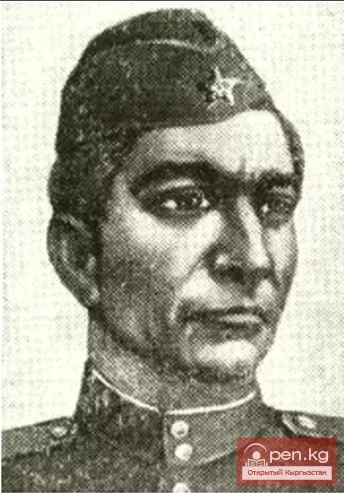

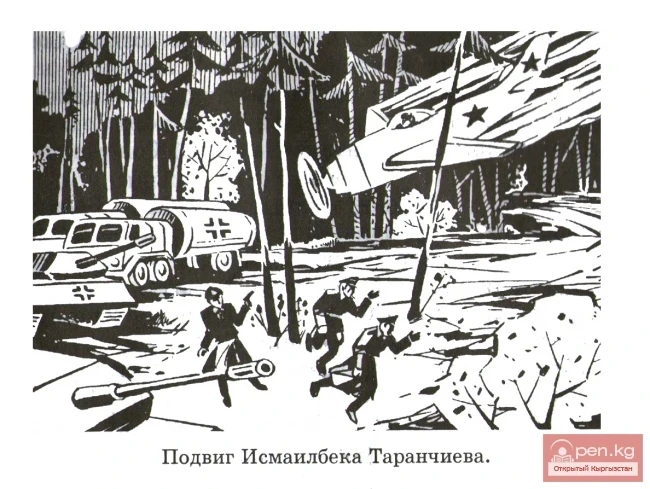

In October, the first general offensive of the enemy faltered. The Nazis began preparing for a new one. It began on November 16. At the Dubosekovo crossing, the defense was held by the Red Army soldiers of the second platoon of the fourth company of the 1075th regiment. Twenty-eight men led by political instructor Klochkov. Among them was Ivan Vasilyevich Moskalenko.

Enemy assault troops advanced on their positions. Without firing a shot. In closed ranks. Like at a parade. They thought that our fighters would not hold, would run away or surrender. And then the machine gun opened fire — right at the advancing troops.

The fascists lay down, waiting. Twenty tanks appeared from a distance, followed by infantry.

— Well, Ivan, it has begun,— said Nikolai Bolotov.

Moskalenko clenched an anti-tank grenade in his hand, waiting for the steel machine to come closer.

This battle has been described more than once. The Panfilovtsy fought heroically against the enemy. They were drenched in blood, fell dead in the snow — but the living continued to fight.

There were fewer and fewer of them. And they had no strength left to hold on. Tanks smoldered before the trenches, and dead fascists lay around, but there was no respite — the enemy launched a new attack. Now thirty tanks stubbornly advanced on the platoon's position, while only 15 men remained.

Ivan Moskalenko ran out of ammunition, there were no grenades. Only two bottles of incendiary liquid. A tank was moving straight toward his trench, and the soldier rose to meet it. The last step in life — a step into immortality.

The twenty-eight did not retreat. They remained at their post.

Hills. Thickets. Snowy field — a field of military glory and valor.

...Two hundred meters from the railway platform at the Dubosekovo crossing, among the overgrown trenches, a granite monument can still be seen from afar, leading to it is an alley of young linden trees. Here, Soviet people come to pay tribute to the best sons of the nation.

And in Frunze, on Young Guard Avenue, monuments have been erected to the Kyrgyzstani soldiers who fought at Dubosekovo.

Now they are forever close, just as they were on that distant November day of forty-one.

The sculptor depicted Ivan Moskalenko at the moment of the highest tension of spiritual strength. An open, simple face, a proud turn of the head — determination in his entire appearance.

They compose poems about them, sing songs. The feat of the twenty-eight will live on forever in the memory of the people.

V. NIKSDORF