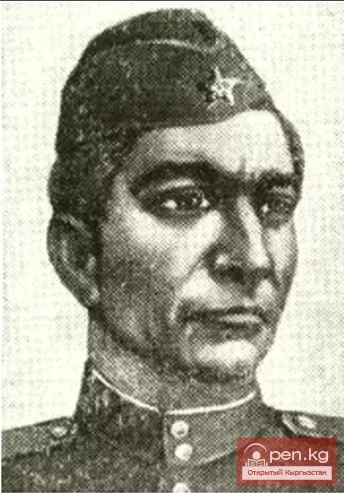

Hero of the Soviet Union Grigory Efimovich Konkin

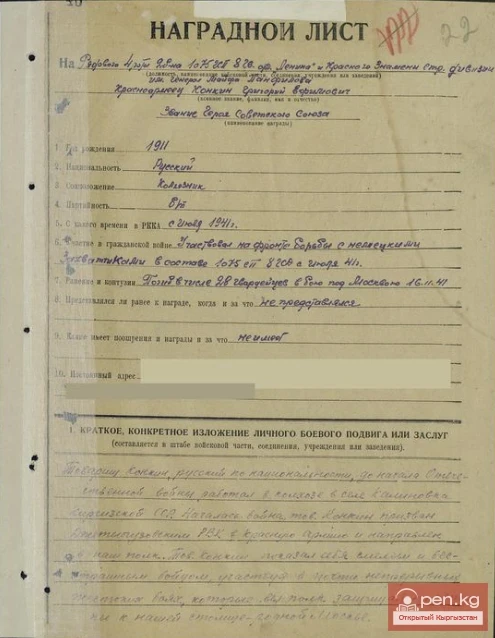

Grigory Efimovich Konkin was a rifleman of the 4th company of the 2nd battalion of the 1075th rifle regiment of the 316th rifle division of the 16th army of the Western Front, a Red Army soldier.

He was born in 1911 in the village of Pokrovka, now in the Jeti-Oguz district of the Issyk-Kul region, into a peasant family.

Russian. He graduated from elementary school. He worked in the collective farm named after V.I. Chapaev.

In the Red Army since 1941. Participant in the Great Patriotic War since 1941.

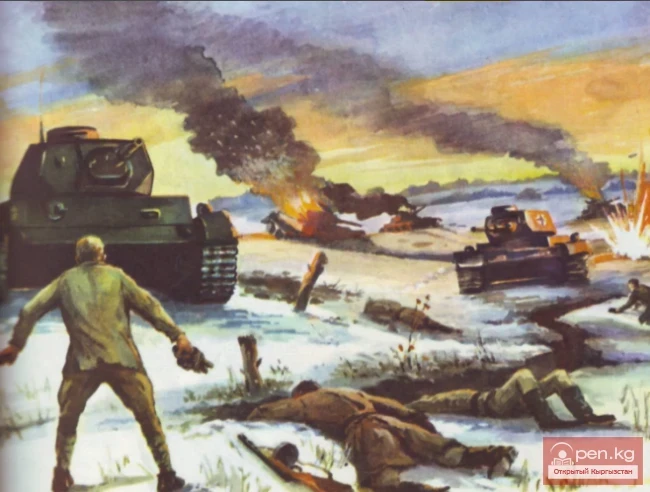

On November 16, 1941, rifleman Grigory Konkin of the 4th company of the 2nd battalion of the 1075th rifle regiment (316th rifle division, 16th army, Western Front), as part of a group of anti-tank fighters led by political instructor V.G. Klochkova and sergeant I.E. Dobrobabin, participated in repelling numerous attacks by enemy tanks and infantry near the railway junction of Dubosekovo in the Volokolamsk district of the Moscow region.

The group, which entered history as the 28 Panfilov Heroes, destroyed eighteen tanks. He fell heroically in this battle. He was buried in a mass grave near the village of Nelidovo in the Volokolamsk district of the Moscow region.

By the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated July 21, 1942, for exemplary performance of combat missions from the command in the fight against the German-fascist invaders and for the courage and heroism displayed, Red Army soldier Grigory Efimovich Konkin was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

Awarded the Order of Lenin.

A museum dedicated to the 28 Panfilov Heroes was opened in the Nelidovo village club. A memorial was erected at his grave. A village in the Jeti-Oguz district, a school in this village, and streets in the city of Przhevalsk and the village of Pokrovka are named after the Hero. A bust of Grigory Konkin was installed in the village of Pokrovka.

THE THRESHOLD OF IMMORTALITY

The bombing, mortar, and artillery shelling had been going on for the second hour. Mixed with snow, crimson-black clumps of earth rose above the trenches, and fragile birches of the Moscow region fell to the cold ground as if mowed down.

Pressing his large body into the narrow niche of the trench, Grigory Konkin managed to glance at his friends between explosions. They were to the right and left, though not as close as he would have liked and as his soul, aching with the anticipation of decisive battle, longed for, but they were still there. Dear ones and close ones.

He missed the moment when the first coal-black giants crawled onto the edge of the untouched white field; he only heard Klochkova's demanding voice: "Tanks! Prepare grenades and bottles!"—and involuntarily cast a glance at the horizon.

Yes, these were enemy tanks. Clumsy, angular, squat and broad-headed.

A sharp chill washed over Grigory, and it trickled down his collar, along his back.

There were many of them, advancing in a fan, threateningly swaying the barrels of their guns, and none of them could be missed.

This was the 147th day of the war and the last day of his life.

Meanwhile, in the distant village of Kalinovka in the Issyk-Kul region, it was nearing noon, and in Grigory Konkin's house, pies were being baked to celebrate the second birthday of his daughter Antonina. And something seemed to resonate in that moment in the soldier, and his heart ached even more for his loved ones.

He was called up in July. In Almaty, where the 316th rifle division was being formed, he was assigned as a private to the third section of the first platoon of the second company of the 1075th rifle regiment. More than four months had passed since then; the moments of farewell with his wife Olga and children were vividly remembered and not forgotten.

He clearly remembered all that past, which was his distant childhood and less distant youth. And with special tenderness, he recalled his first meeting with Olya...

The son of a peasant, who began working at the age of eight, he learned well what forced labor was.

The owner for whom Grigory worked tied him, the boy, to the saddle—this was safer, he wouldn’t fall off if he fell asleep—and for hours forced him to drive a horse with a harrow across freshly plowed fields. His legs went numb, his body became stiff, his back ached, blood circles spread in his eyes, and the long exhausting day seemed never-ending.

Once, exhausted and dazed from the not-so-childish strain and heat, he couldn't handle the stubborn horse and, in frustration, pulled the reins more sharply than usual. Unexpectedly backing up, the horse got tangled in the harness and fell on its side, nearly injuring the boy. But there was no pity for him. After giving Grigory a slap on the back of the head, the owner calmed the horse.

In 1928, when he turned seventeen, his father took him to the market, and in the evening they returned leading their own horse. Sullen, disheveled, but their own.

Yes, life was getting better; everyone felt it. A few years later, about twenty kilometers from their native Pokrovka, a new village called Kalinovka appeared—a estate newly organized specifically for landless peasants of the collective farm named after Chapaev, and the Konkins, having given up their horse and cart, became full members of it.

Grigory did not shy away from work, doing everything assigned to him diligently. He plowed and sowed like his father, built roads to mountain pastures, but he loved carpentry the most. The feeling of the light, obedient axe in his hand was the most pleasant sensation for him.

Yes, this was probably his main peasant talent, which he discovered quite unexpectedly when he suddenly felt the urge to modify the collective farm's thresher. And he modified it; everyone liked it, and it was noted that it became easier and more convenient to work with it.

Inspired by success and a valuable gift from the administration, he soon began to carry out the idea of portable feeders and convinced others that they were necessary. Then he started building lightweight collapsible houses for shepherds.

He lived calmly and confidently on his land, finally knowing the long-awaited joy of free labor, and now, finding himself in the cold forests of the Moscow region, he was ready to sacrifice for this freedom, at least for his children, if not for himself, even his life.

His father, an old soldier of the tsarist army, Efim Savelyevich, always taught restraint but knew how to take risks when necessary. Once, on the way to Jeti-Oguz, bandits blocked their path.

— Calm down, don’t be fidgety,— warned Grigory's father. — There’s nothing for them to take from us; let’s not get involved.

And indeed, after glancing quickly at their cart and horse, the bandits parted.

But another time, hearing gunfire on the steep bank of the lake and calls for help, his father jumped off the cart and, shouting “Surround them! Take them alive!” rushed to help the young border guards trapped in a pinch.

And he rushed just in time, calculatingly, even though he was unarmed. He not only saved the boys' lives but also helped detain several bandits...

The cannonade subsided, and the tanks stubbornly crawled toward their height. The tension in the trench reached its peak; Grigory felt it, and his thoughts kept flying away somewhere. His fellow countryman Grigory Petrenko was comfortably laying his rifle on the parapet. Ivan Moskalenko, gripping a grenade in his hand, seemed frozen like a stone statue. Even further, barely peeking out of the trench, Grigory Shemyakin and Nikolai Ananyev froze, as if preparing to leap.

With these people, he was connected not just by regional ties; they were bound by the strongest and most sacred bonds of combat brotherhood.

Already at the end of August, on the way to the Leningrad front, their train was attacked from the air near the Uglovka station, and they had to come to each other's aid. They unloaded in Borovichi under pouring rain, marched nearly a hundred kilometers, and instead of the front line, which they so eagerly sought, found themselves in the reserve of the Supreme Command Headquarters as part of the 52nd army.

But they did not have to remain inactive for long. On October 10, during the peak of the Nazis' preparations for the second general offensive on Moscow, the division was transferred to the Volokolamsk area and entered battle on October 14.

In the past month, Grigory experienced the bitterness of the first retreat—after two days of stubborn fighting for the city, on the evening of October 27, they were forced to retreat, and the first joy of intoxicating success was heightened by the news of our troops' parade on Red Square on November 7.

The tanks were very close; in a minute or so, they could be bombarded with bottles and grenades. Now he heard and saw nothing except the approaching clank of tracks and the painted hateful crosses on the armor.

His heart beat faster and sometimes seemed to stop. The soft, bluish-gray snow melted under his cheek.

What did he remember in that last moment of life on November 16, 1941? That his little daughter Tonya turned two today and that his wife, as per tradition, was treating all the children with soft, fragrant pies piled high on the table? Or how he first approached her in the meadow and helped her adjust the scythe, blushing with awkwardness and trying not to meet her fiery gaze? No one will ever know this now. But he could not help but remember it and could not help but be carried away by the willful thought to his native Kalinovka, could not help but walk on the new creaky floorboards that he had laid just before leaving for war with his sons Nikolai and Anatoly; his wife Olga Semyonovna had no doubts until the last moment. And a mother's intuition is the greatest intuition on earth. It cannot be doubted.

And again, in the distance, the familiar figure of the political instructor flashed, and the first grenade exploded under the track of the enemy vehicle.

- Come on! Come on! Hurry up, enemy— said Grigory, gritting his teeth. — Let’s see whose will prevail.

As if pondering, the tank with the cross on its armor slightly moved its blunt face with the short barrel of the gun, but then immediately picked up speed again.

And again, now from the left, a sharp crack of a grenade explosion was heard. Another armored giant froze, as if it had bumped into an invisible obstacle.

Shchepetko was firing short bursts from the machine gun at the fleeing tankers; smoke and stench filled the trench. Everything around buzzed, howled, and shrieked. Everything shook from the explosions and moaned.

The polished tracks of the enemy giant gleamed dull against the snow and earth. If they let it pass, it would go further. And it would rumble with its clanking steel joints across the very square where just ten days ago, their hearts were stirred by the parade of our troops, and over which, amplified by loudspeakers, the calm, self-assured voice of the soldiers of the Motherland echoed, familiar to millions of people.

No, it must not pass. And it will not pass. Better to die than to let it through.

His eyes were blinded by tension. Something seemed to sway very close, like on the waves of blue evening Issyk-Kul. He did not want to believe that everything was serious—war, death, that this was not a dream but reality.

And he did not want to die...

Machine-gun bursts pierced the air above their heads, embedded themselves in the snow nearby, and the hand gripping the bottle was increasingly filled with strength. And his peasant hand hardened, as it always did, barely resting on the handles of the plow.

He had to do this. To do it confidently and reliably.

The tank was about fifteen meters away.

“It’s time,” Grigory commanded himself and squinted, bending for the throw.

He waited a long time for the sound of breaking glass. Probably longer than the tank's approach itself. But he heard it, despite the roar of the engine, the explosions, and the whistling of bullets; he would have heard it even in a hundredfold more deafening chaos, having found himself completely deaf at that moment.

A fiery stream of his holy vengeance flowed eagerly down the frosted armor. Thin, seemingly unstable. But spreading and spreading. Mortally wounding the enemy.

The field, which had been smooth and white like fluffed cotton just fifteen minutes ago, lay before him all torn up, crumpled, crushed by the tracks. It smoldered and seemed to writhe from the wounds inflicted upon it.

Another giant, roaring victoriously with its engine, rolled over the trench. But at that moment, another Grigory, Grigory Petrenko, rose as if from under it. A grenade exploded. The monster with crosses on its armor jerked, turned on its surviving track, and drenched Petrenko with a hail of machine-gun fire. Petrenko fell. Slowly and forever.

Emtsov and Trofimov lay, their arms unnaturally sprawled on the parapet.

And the machine-gun fire swept through the trench, capturing him with its hot wing. And everything dimmed in Grigory's eyes. Something sharp and deep entered him, exploded into a myriad of dazzling sparks...

Suffering heavy losses, the enemy retreated, but not for long. Soon a new, even denser avalanche of steel monsters with crosses, a rare chain of machine gunners moved toward height "251.0". And again, already shrouded in glory and immortality, the Panfilov heroes stood in their way. All 28. Alive and dead. Because even the dead, in this decisive hour of battle, inspired the living with their heroic death.

Some time later, a letter arrived in the village of Kalinovka in the Jeti-Oguz district.

“To you, dear friend of the Hero of the Great Patriotic War Grigory Efimovich Konkin, the commanders and political workers of the unit where your husband served send their fiery guard greetings,— wrote the unit commander Colonel Karpov and the military commissar, battalion commissioner Mukhamedyarov. — Together with you, dear Olga Semyonovna, we share the grief over the premature death of your husband and our comrade-in-arms, Grigory Efimovich Konkin, whose bright image will forever remain in our memory.

Our loss is heavy, but for every drop of sacred blood spilled by us, the fascist fiends will pay with a torrent of their own.

We are merciless, and no occupier will leave our land alive.”

In the collective farm named after Chapaev, sowing was underway, and at the general meeting, the farmers promised to complete all fieldwork ahead of schedule. Ploughmen Ivan Svetlopuzov and Vladimir Pyshkin, who once began working under Grigory Konkin's guidance, vowed to work for two.

“When you go to the front, be a real soldier,” I instructed Grigory at parting,— shared Grigory's father Efim Konkin in those days in the regional newspaper,— Beat the damned fascists while you have the strength, destroy them, you bastards! And if anything happens, Grisha, don’t let yourself be taken alive. My son fulfilled this command. Together with his comrades, he fought bravely against the enemy tanks and did not let them reach Moscow. Grisha died a hero's death, he did not falter, he elevated my old age. I am proud of his combat deeds. I still have two sons in active service: Andrey and Ivan. Andrey recently sent a letter saying he recovered from his wound and is going back to take revenge for his brother.

And we, the old men, will work for them here, on the land.”

The old soldier did not wait for his sons...

In April 1975, Kalinovka was renamed Konkino, the Hero's name was given to the primary school and one of the streets in the district center Pokrovka, and the steamboat "G. E. Konkin" plows through seas and oceans.

And his lineage did not end. The eldest son Nikolai worked as the chairman of the native collective farm, his labor marked by high government awards, and now heads the Irdyk village council. Another son, Anatoly, also remained true to the land and his father's duty. He works as a mechanic in the native collective farm.

In August 1964, the first cosmonaut of the planet, Y. A. Gagarin, visited their ancestral home and took a photo with the sons and daughter of the Hero-Panfilov.

A. SOROKIN