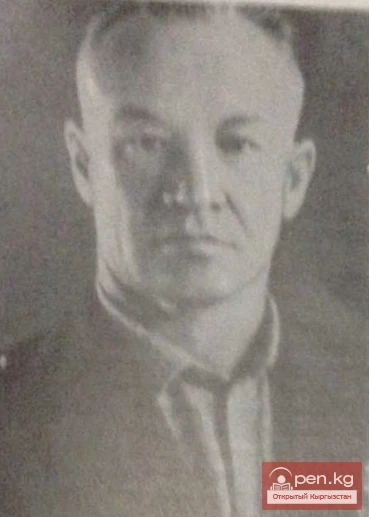

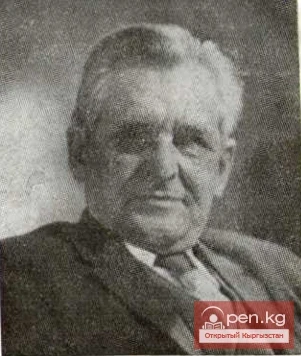

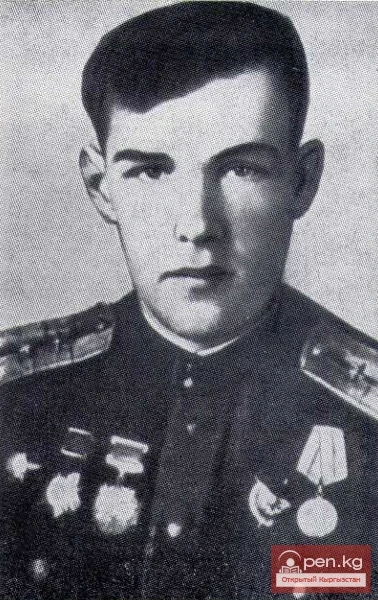

Hero of the Soviet Union Alexander Vasilievich Fukovsky

Alexander Vasilievich Fukovsky was born in 1920 in the village of Zarubitsy, Monastyryshchensky District, Cherkasy Oblast, into a peasant family. He was Ukrainian and a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU).

In 1938, he moved with his mother and older brother to Kyrgyzstan, to the city of Osh. In the autumn of 1939, he was drafted into the Soviet Army and sent to serve in the Baltic Military District.

Guard lieutenant. Commander of a motorized rifle company of a mechanized brigade.

He participated in the Great Patriotic War from the very first days, fighting on the Kalinin Front.

On October 17, 1943, for his courage and bravery displayed during the crossing of the Dnieper River and holding a bridgehead on the western bank, Alexander Vasilievich Fukovsky was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

After the war, the Hero continued to serve in the ranks of the Soviet Army. In 1947, he graduated from the Military Academy of Armored Troops named after Lenin. In 1980, Colonel A.V. Fukovsky retired and continued to work in the State Committee for Science and Technology.

CONTACT PASSWORD: "TAIFUN"

At the Moscow Machine Gun and Mortar School, which was now located in Kazan, Alexander was first required to undergo a medical examination again, and only after that was he given a piece of paper to write his autobiography. He dipped his pen in the inkwell and began to write:

“I, Alexander Vasilievich Fukovsky, was born on October 10, 1920, in the family of a peasant in the village of Zarubitsy, Monastyryshchensky District, Cherkasy Oblast, Ukrainian SSR. Here I began my studies at a rural school.

In 1933, we suffered a terrible tragedy — my father died. My mother gathered our modest belongings, and we moved to my older brother Andrei, who at that time lived in Central Asia and worked as an accountant at the Kokand cotton gin.

In five years, my brother managed to teach me his trade so well that when we moved to the city of Osh in the Kyrgyz SSR in 1938, where my brother was assigned to a new job, I was able to work as an accountant on my own.

The year I graduated from evening school, I was drafted into the Red Army. I graduated from the regimental school in the city of Jelgava, Latvian SSR, where I received the specialty of tank driver-mechanic and the military rank of sergeant. Others were sent to units, but I was left to train the new recruits.

On the day the war began, we were alerted. Taking our places in the tanks, we moved towards the border. It was here that I participated in battles with the fascists. In a month and six days, our tank shot down three enemy vehicles, but on July 27, a shell hit us, one of my soldiers was killed, and I was seriously wounded.

I spent six months in a hospital near the city of Gorky, and upon recovery, I prepared marching companies in the Gorokhovets forests, also near Gorky...”

...Of all the military disciplines taught at the school, Alexander preferred tactics. Here, as in real combat, one could engage in battles with the enemy. How pleasant it was to emerge from such a battle victorious!

Especially when, in such a case, everyone in the course would say: “Well done! You have resourcefulness.”

Upon completing his studies, Alexander was sent to the Kalinin Front as a platoon commander of the 18th mechanized brigade of the 32nd rifle division of the 2nd mechanized corps. He arrived there on the eve of the unit's redeployment to the area of Velikiye Luki, where fierce battles were taking place at that time. The troops of the Northwestern, Kalinin, and Left Wing of the Western Front had been conducting an offensive in the areas of Demyansk, Velikiye Luki, Rzhev, and Sychevka since November 1942, aiming to divert enemy forces from the “North” and “Center” army groups and prevent them from assisting the surrounded enemy group near Stalingrad.

The enemy held Velikiye Luki for a long time, even when its outskirts were in the hands of retreating forces. Finally, our troops managed, using tanks and artillery, to drive the occupiers out of there. The enemy retreated from the city and began to accumulate forces to regain lost positions. There was not a day without skirmishes with the fascists.

For Alexander Fukovsky, who was appointed commander of the brigade's combat security at that time, the entire winter and spring of 1943 were spent in night raids beyond the front line with a sniper rifle. This was one of the duties of the combat security commander. He had to constantly go out with his subordinates to hunt for unsuspecting enemy officers and drivers.

Following the common tradition, he also began to keep score of his successes with small notches on the stock of his rifle. The number of these notches approached two dozen when he was unexpectedly summoned by the brigade commander, Colonel Maximov.

— Well, how are things, lieutenant? — he greeted Alexander with a question.

— Not bad, — he replied.

— Don't you think you've been sitting in the platoon too long?

— The command knows better, — Alexander shrugged.

— They know better, and therefore you will take command of the 1st motorized rifle company.

He had to take command of it in the echelon that was transporting the 18th brigade along with the entire 2nd mechanized corps towards the city of Mtsensk in the Oryol region.

The advancing Soviet armies actively used large mechanized units and formations for breakthroughs.

Among them was also the 18th mechanized brigade of Colonel Maximov.

It moved slowly, with endless battles, and after a week, it completely stopped near a small village called Ivanovka in the Oryol region. At the approaches to the village, the fascists held the dominating height, which allowed them to easily decipher and anticipate all the maneuvers of the brigade.

It became clear that without taking this height, there would be no further path westward. Colonel Maximov assigned this operation to Fukovsky's 1st motorized rifle company, providing it with several tanks and self-propelled guns for support.

Fukovsky placed only a small part of the company on the tanks; they were to storm openly to distract attention from the main group, which was maneuvering to encircle the enemy.

Under the cover of night, the main group, led by the company commander, silently infiltrated enemy territory and lay down at the foot of “Nameless,” as the height was marked on the map.

At the appointed time, the tanks and self-propelled guns began their advance from the brigade. The height suddenly came alive, the Germans began to run around and shout. Then shells sent from our tanks and self-propelled guns began to explode up there. And when the explosions became more frequent, Alexander fired three green flares into the sky, which were the conditional signal.

By morning, the 18th mechanized brigade was already far from “Nameless,” and pleased with such success, brigade commander Maximov said to the commander of the 1st company:

— Well done, well done! I am recommending you for the Order of the Red Star.

Fukovsky received this first award three weeks later when the brigade, after fighting through the cities of Konotop in Sumy Oblast, Bakhmach, and Nizhyn in Chernihiv, rushed after the retreating enemy to Chernihiv. Here, on the march, the brigade received two pleasant pieces of news at once: a decree was issued by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR transforming it into the 24th Guards Brigade and naming it after Nizhyn for the recently liberated city of Nizhyn.

The joys of this day were destined to last. In the evening, Maximov summoned Alexander to him.

— Here’s the thing, Fukovsky, there is an order to reach the Dnieper as quickly as possible and not allow the fascists to establish themselves on its western bank. But, as you understand, the entire brigade cannot move at a fast pace. Therefore, we decided to create a special assault detachment of about a hundred men, equip it with several tanks and self-propelled guns, and provide more machine guns and mortars. What do you think, can such a detachment keep up with the enemy and, if necessary, nip at their heels?

— It should be able to.

— That’s what I think too, it should be able to. I appoint you as the commander.

The assault detachment set out that very night. As Maximov had warned, representatives of the partisans — a gray-haired woman and a fourteen-year-old boy — met the detachment at the highway.

— Our people are preparing to capture the crossing, but not here, rather closer to Kyiv; we were sent because we are from Kosachevka, more precisely from the opposite bank, from Chernobyl, the woman explained. We know the area, we will guide you.

The enemy had significant forces in this area. It was necessary to look for another crossing. The partisans suggested taking the right one, just opposite Chernobyl; there they could even get boats from the local population.

Fukovsky sent them for boats and contacted Maximov to inform him about everything.

The brigade was already close. The commander gave permission to relocate the crossing to another location.

After drying off and resting a bit, the detachment hurried after its guides, who categorically refused to rest a second time.

There were three boats, quite spacious, and after the failed attempt to cross, the number of stormtroopers had significantly decreased, so everyone fit in. They set off. They were almost in the middle of the river when rockets suddenly soared from the opposite bank, followed by the howling of shells. One of them hit the last boat directly. Alexander only noticed that almost no one remained alive among those who had been in it when his boat bumped into the sand.

— Forward, follow me! — he shouted, leading the soldiers to the shore.

He ran and constantly felt, rather heard, the thud of several feet behind him, and this gave him strength. He threw grenades at the enemy machine-gun post, cut down a fleeing soldier with a burst from his automatic rifle, and finally, feeling that tracer rounds were getting closer around him, he dropped to the ground. The same was done by those who were running behind him.

Catching his breath, he passed the order down the line:

— Take up circular defense, dig in.

The fascists maintained a heavy fire all night, but they themselves did not advance until morning. As dawn broke, the first explosions of shells erupted in the clearing, which, in general, could do little unless they hit directly, because during the night Fukovsky's stormtroopers had managed to dig in well.

After the artillery bombardment, the infantry moved in. They let it get closer and killed part of it, scattering the rest with automatic fire and one machine gun; Fukovsky ordered the other machine guns to remain silent just in case.

The next attack by the enemy began with a large unit. Fukovsky allowed only one machine gun, which had already revealed itself, to be used, and only at the most critical moment, when the machine gunner was killed, did the next one open fire. This decided the outcome of the attack.

With their bold and decisive actions, the mortarmen under the command of Guards Lieutenant A.V. Fukovsky provided highly effective fire support to the rifle units in capturing and holding the bridgehead.

Guards Lieutenant Alexander Fukovsky, along with the soldiers of the mortar company, participated in repelling numerous enemy counterattacks.

By the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated October 17, 1943, for courage and heroism displayed in the struggle against the German-fascist invaders, Guards Lieutenant Alexander Vasilievich Fukovsky was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, with the Order of Lenin and the Medal of “Gold Star” (No. 1226).

After the war, A.V. Fukovsky continued to serve in the army. In 1947, he graduated from the Military Academy of Armored and Mechanized Troops. Since 1976, Colonel Fukovsky A.V. has been in reserve.

Retired Colonel A.V. Fukovsky lived in Moscow. Before retiring, he worked in the State Committee of the USSR for Science and Technology. He died on May 2, 1997. He is buried at Troekurovsky Cemetery in Moscow (section 4).

He was awarded the Order of Lenin, the Order of the Patriotic War 1st class, 2 Orders of the Red Star, the Order “For Service to the Motherland in the Armed Forces of the USSR” 3rd class, and medals.