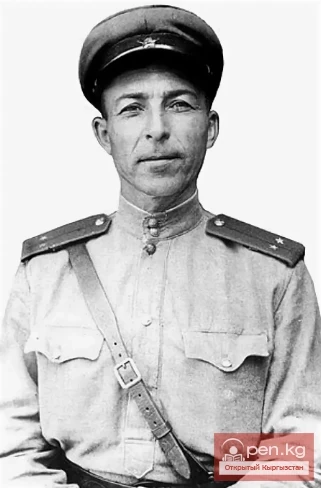

Hero of the Soviet Union Stepan Zakharovich Sushchev

Stepan Zakharovich Sushchev was born in 1914 in the village of Georgievna, Pishpek County. Russian.

In 1931, he moved with his parents to the city of Frunze. Since 1933, he began his independent working life at the Frunze brick factory as a transport worker. He served in the Soviet Army since 1937. Senior sergeant.

Assistant commander of a platoon in a rifle company. Party organizer of the company.

In October 1941, he was sent to the front. He fought as part of the Central Front. He was highly respected by the soldiers and officers. He sustained five wounds.

On October 17, 1943, for his courage, bravery, and heroism displayed during the crossing of the Dnieper, Stepan Zakharovich Sushchev was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

After demobilization in 1946, he returned to Kyrgyzstan and settled in the village of Belovodskoye. He worked at a motor transport base as a battery technician and mechanic. Since 1978, he was retired.

By order of the commander of the internal troops of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Kyrgyzstan, he was enrolled as an "Honorary Soldier" of the military college of internal troops (Bishkek). In May 2006, a bust of the Hero was unveiled on the college grounds.

Died: July 24, 2008.

HEROES OF THE BATTLE FOR THE DNIEPER

Having drained the enemy's strength in a fierce defensive battle on the Kursk Bulge, the Soviet troops went on the counteroffensive. North of Kursk, the stubbornly resisting enemy was pushed westward by the 112th Rylsk Rifle Division. In the fifth company of the 416th regiment of this division fought Kyrgyzstani Stepan Zakharovich Sushchev. In continuous bloody clashes, Stepan and his comrades fought inch by inch to reclaim their native Soviet land from the fascist invaders.

The battle on the northwestern outskirts of Fatezh was particularly fierce. Here, in the area of the alcohol plant, the fifth company encircled a significant group of Hitlerites, who, having rejected the offer to surrender, repeatedly made desperate attempts to break through the encirclement, each time encountering the unwavering determination of the Soviet warriors not to let the enemy escape the trap and to crush their resistance.

In that memorable battle, during one of the hand-to-hand fights, senior sergeant Sushchev was wounded in the thigh and lost a lot of blood. He was placed in a field hospital right there in Fatezh, given first aid, and then sent by ambulance with other wounded to recover in Kursk. Lying in the hospital bed, a soldier thinks a lot and well.

With warm sadness in his heart, Stepan thought of his relatives and loved ones, of his wife, of his little daughter, mentally trying to imagine what they were like now, how they lived, and worried—were they not suffering? Valya writes that everything is fine with them, they lack nothing. But she is like that: she won't bother him with her sorrows. Stepan knows himself that they are not having an easy time, oh, how hard it is for them now. And what is there to be surprised about? War! The whole nation is enduring hardships, sacrificing much for the defeat of the enemy.

In her letters, his wife increasingly asked about his life at the front, and he answered her questions briefly: "Alive, healthy, fighting." Now he would write that he was wounded. But this should not be reported now, later, when he recovers and returns to his unit. "Look, Valya, your husband was wounded, but now, thanks to our glorious doctors, he is healthy again and continues to fight the fascist scum." And the wound, fortunately, heals quickly, and senior sergeant Sushchev will not linger in the hospital.

Stepan remembered his first wound and involuntarily smiled. It happened in early November forty-one.

After covering more than three thousand kilometers from the station of Pishpek to the forests near Moscow in six days, the military train stopped at some inconspicuous halt south of the capital, and unloading began. The soldiers had not yet managed to form up by platoons and march to the forest when a growing, soul-stirring roar was heard in the sky. The platoon commander shouted: "Air! Everyone to the forest! Faster, faster!" Stepan ran with everyone to the saving forest, while above, the roar continued. For a moment he stopped, tilting his head back, he saw a plane in the sky, even saw how a whole handful of bombs detached from one of them and, spreading out like a fan, howled down to the ground.

The bombs exploded somewhere behind, causing no harm to anyone. After dropping their deadly cargo, the bombers with black-and-white crosses flew west. But a few minutes later, the familiar roar reappeared in the sky, heralding the arrival of a new flock of fascist vultures. These bombed more accurately. Shrapnel caught up with the soldiers who had already taken cover in the forest, and the first dead and wounded appeared. And the "Junkers" flew over the forest edge again and again, carrying out their dark deeds with impunity. It was then, already in the forest, that Stepan was wounded. A heavy thud sounded somewhere very close, and the next moment he felt a sharp pain in his shoulder, so strong that he lost consciousness for a while. When he came to, his shoulder burned like hellfire, and his arm hung like a rag.

"I've fought enough," Stepan thought bitterly on the way to the field hospital. The most annoying thing was that he was not wounded by a shrapnel, but by a heavy log that had flown off from a nearby forest hut, which had been hit by a bomb. "Does it hurt?" asked the nurse who was bandaging him. "Oh, it hurts here!" Stepan hit himself on the chest with his healthy hand. "It's okay, soldier, don't worry. You'll have enough war for your lifetime," the woman said with a smile.

Her words came true. But Stepan Sushchev realized this later. Back then, in November forty-one, he seriously considered himself a failure. And how else could one think? Since thirty-seven, Stepan had been in the army, in the NKVD troops, his term of active service had expired—he remained for an extended term. He became a Komsomol member in the army. On June 22, 1941, he submitted a report to the command requesting to be sent to the front. He was happy when his request was granted. And when in September forty-one he was assigned to the regimental reconnaissance company, he was also happy. He trained tirelessly, eagerly and meticulously absorbed everything he was taught. And on that long-awaited day, October 26, when the train with the first units of the division formed in Frunze, including the regimental reconnaissance company, departed from the platform of the Pishpek station, Stepan Sushchev's heart beat excitedly and joyfully.

On the way to the front, Stepan already saw himself as a fearless and skilled scout, carrying out particularly important missions behind enemy lines. He vividly imagined how he would capture his first "prisoner," how the fascist would desperately resist, perhaps a shootout would ensue, and he, Stepan, would be wounded, but overcoming the pain, would do everything necessary: "They won't let the 'prisoner' escape, they will deliver him, for which they will be thanked by the command..." And now he was wounded, but not at all as he had imagined.

In the hospital of the suburban city of Orekhovo-Zuyevo, Sushchev stayed for three months. Since he was a "walking" wounded, he was required to study at the courses for medical orderlies. And although the prospect of retraining as a medic was least appealing to Stepan, there was nothing to be done: an order is an order. At the end of January forty-two, Sushchev and three other newly minted medics were sent to the disposal of the headquarters of one of the units of the Bryansk Front.

But while they were getting there, the need for medics in that unit had disappeared, but at that time combat crews for anti-tank rifles were being formed, and Stepan asked to be assigned to the tank destroyer platoon. He was accepted. Thus, Sushchev became an anti-tank gunner. Later he was transferred to the rifle company, which became his front-line family for a long time.

And again, the front-line routine flowed—combat, marching. Senior sergeant Sushchev marched along the roads of war, which led through the Ukrainian cities of Bakhmach and Nizhyn, across the Desna River, and at the end of September forty-three, brought Stepan and his comrades to the Dnieper.

A great battle for the Dnieper was ahead. By this stage of the war, Stepan Zakharovich Sushchev had come as a communist (he joined the party during the July battles near Kursk), a party organizer of the company. It was he whom commander Voronov entrusted to lead and prepare a shock landing group for the crossing of the Dnieper, which was to be the first to land on the western bank, capture a foothold near the village of Yasnogorodka, and hold it as long as necessary, ensuring the crossing of the main forces of the regiment. Many volunteers wanted to go with the party organizer on this responsible combat mission, but Stepan Zakharovich selected the bravest and strongest, the most daring and experienced, taking with him those he trusted as himself.

The crossing began the day after receiving the order, September 27, at 4 PM. On the ferry built the day before, resembling a catamaran—two large fishing boats tied together with logs and boards—the landing group was placed: thirty-two volunteers. In extraordinary, incredible silence, improbably devoid of the sounds of war, the ferry reached the middle of the river. And it was here that a fascist "frame" appeared high in the sky and seemed to hover over the river for a moment. No one among the soldiers needed an explanation of what this meant: they rowed harder and prepared their rifles for battle.

The "frame" left, and the "Messerschmitts" arrived. They descended rapidly one after another and raked the water's surface with bullet trails. The planes attacked the ferry twice, and both times their machine guns missed. At that time, enemy machine guns opened fire from the shore. "No, we can't tempt fate any longer," thought Stepan Zakharovich, watching the flock of fascist vultures flying away into the sky. "Next time they won't miss..." And, making a decision, the senior of the landing group commanded: "Guys! Grab your weapons and follow me!" He jumped first into the Dnieper water, and the other soldiers followed him. This unplanned swim saved many of their lives. As soon as the ferry emptied, the deck where the paratroopers had just sat was instantly pierced by the bullets of the "Messerschmitts," splintering the wood.

The September water burned Stepan with such fierce cold that he gasped as if someone had tightly squeezed his throat, and his heart stumbled, as if it had tripped, and then began to pound like crazy. The current swept him away. Struggling against it, he tried to swim to the shore, but soon ran out of strength. And no wonder: he had a rifle around his neck, grenades on his belt, and a pouch with spare magazines, and his clothes were soaked. But Stepan continued to swim.

His arms and legs grew weaker, his exhausted body sank more frequently beneath the water, but he kept surfacing from the depths of the Dnieper. He saw nothing before him, heard nothing, blood pounded wildly in his temples, and only one thought pulsed in his muddled consciousness: "Swim to the shore, swim... I must carry out the order..."

Senior sergeant Sushchev swam and did not immediately realize it when his feet touched something solid, once, twice, three times... Along with him, thirty soldiers of the group reached the right bank of the Dnieper, which dropped off to the water with sandy cliffs, scattered in different places—this is how the current had thrown them. They gathered and waited for their comrades for a while, but those two never swam out. Apparently, the fascist bullets got them. And although many dangers awaited them ahead, at that moment, many felt that the main trial was already behind them. Senior sergeant surveyed his comrades with an encouraging look and, meeting their eyes filled with unwavering determination to go through everything with him to the end, where the enemy was hiding above, said excitedly: "Well, guys, it's time..."

That day, combat luck was on the side of the paratroopers. However, it is always with those who are brave and decisive, resourceful and courageous. Discovering machine gun nests on the approaches to the village of Yasnogorodka, Sushchev decided to destroy the crews and capture the machine guns. He and several other soldiers stealthily approached the machine gun from the rear through a ravine, and, quietly finishing off the crew, donned trophy camouflage jackets, put helmets over their caps, and then, no longer hiding, began to shoot occasionally towards the river, just as the other enemy machine guns did, only raising the barrel slightly higher. The trick worked: the Germans did not notice the substitution of the crew.

Meanwhile, another group of paratroopers was sneaking up to a neighboring machine gun pit with the same goal, which was located further away, about one hundred and fifty meters. Watching the "neighbors," Sushchev noticed that three Germans were repeatedly rising above the parapet, trying to see something better ahead. This cost them their lives: when they peered out once again, the senior sergeant could not stand it and fired a precise burst. A minute later, the surviving one jumped out of cover and shouted with all his might, waving his fists for greater persuasion. And although he shouted in German, everything was clear without a translator: "What are you doing, donnerschlag, shooting at your own!" He did not shout for long: someone from that second group, which was going to capture that machine gun, shot the German dead.

The crew of the third enemy machine gun was now doomed. They all understood, but it was already too late. With powerful fire from the trophy machine guns and rifles, the paratroopers predetermined the outcome of the short duel. They fortified themselves in the captured positions, aimed the machine guns at Yasnogorodka, from where unwelcome guests could soon arrive, and signaled to the eastern bank: it was time to cross. The fascists did not take long to respond. Their first attack was bold and overly confident, for which they paid dearly. Allowing the attackers to get closer, the soldiers, at the command of the party organizer, met them with short, aimed bursts. The Germans hastily retreated. After a while, they attacked again and were forced to retreat once more.

The enemy's attacks became fiercer and more aggressive. That day there were seven of them. All seven were repelled. Unable to break through the Soviet defenses from the front, the fascists tried to outflank the defenders of the foothold, but they failed in that too. Meanwhile, the balance of power changed every hour in favor of the Soviet warriors. The fifth company, led by its commander Semykin, joined the landing group, and other units of the 416th rifle regiment took positions on the right and left. And the crossing continued. The courage and steadfastness of senior sergeant Sushchev and his comrades allowed the sappers to build a pontoon bridge, and military vehicles began to cross to the western bank.

On the morning of September 28, the 416th rifle regiment began its offensive. The Germans resisted fiercely, but the pressure from the Soviet warriors was so strong that soon the battle moved to the streets of Yasnogorodka. Semykin was killed. Taking command, the party organizer Sushchev led the fifth company into battle. Driving the enemy out of the village, the soldiers continued their advance, deepening and expanding the foothold. From the small piece of land captured by Sushchev's landing group, it grew into a significant area liberated from the enemy, up to twenty kilometers wide and twelve kilometers deep...

Then there were battles for Korosten and Zhytomyr. In December forty-three, Stepan Zakharovich was wounded again. And once more—a hospital, this time in the distant Ural city of Troitsk. There he learned about being awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. This was how the Motherland assessed his military feat in the great battle for the Dnieper.

From the hospital in the summer of forty-four, Stepan Zakharovich was sent to junior lieutenant courses in the city of Shadrinsk, also in the Urals. Then back to the front. Battles for Königsberg. The war was nearing its end. Sushchev met victory as the commandant of the western sector of the city of Allenstein in East Prussia.

The war ended, and peaceful life resumed. Stepan Zakharovich returned to his native land and actively engaged in nationwide work to restore the economy of the country devastated by the ravages of war. Until his retirement, Stepan Zakharovich Sushchev selflessly worked in the working collective of the Belovodskoye motor transport base. On the chest of the veteran, next to the Order of Lenin, the Gold Star medal, and other combat medals—awards from the Motherland for his outstanding labor.

V. KIRYANOV