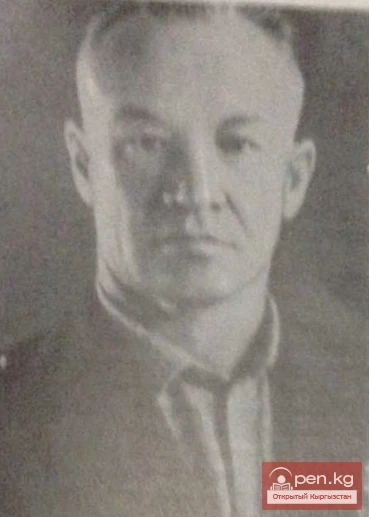

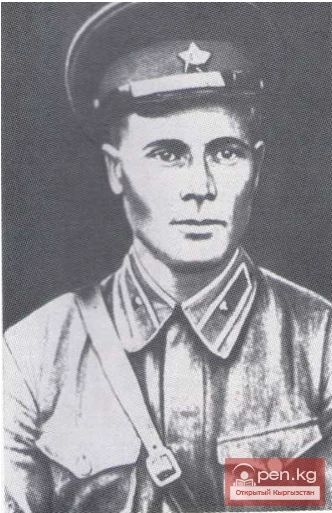

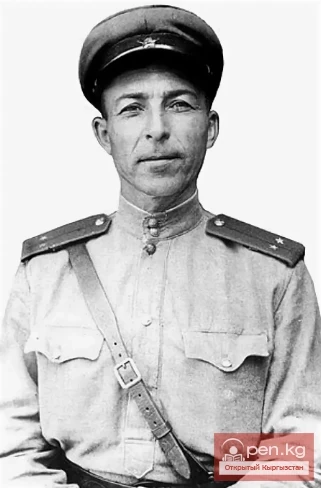

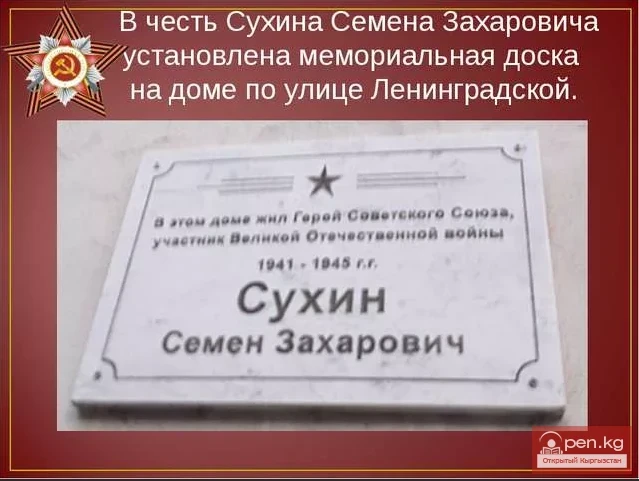

Hero of the Soviet Union Semen Zakharovich Sukhin

Semen Zakharovich Sukhin was born in 1905 in the village of Orlovka, Tugan district, Tomsk region, in a peasant family of modest means. He was Ukrainian and a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). Since 1935, he lived in the Kirghiz SSR in the village of Kirovka, Talas district. He was drafted into the Soviet Army in September 1941, serving as a platoon commander and lieutenant.

He participated in battles on the Western and 2nd Belarusian fronts. For his courage and bravery displayed during the crossing of the Neman River, capturing and holding a bridgehead on the western bank, Semen Zakharovich was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. For his combat merits in the Great Patriotic War, he was awarded the Orders of the Red Banner, the Patriotic War 1st class, and the Medal for Courage.

After the Great Patriotic War, Semen Zakharovich Sukhin lived in Kyrgyzstan, then moved to Tomsk. He died in 1971.

THEIR FRONT

For several weeks, the battalion had not emerged from combat. A major offensive was underway across the front. Just half a month ago, there was the Dnieper. The division had only just gotten used to the honorary addition to its number — the 64th Mogilev.

And now ahead — Grodno.

Without reports and political discussions — only by the changing names of Belarusian towns and villages — the soldiers saw that the war was rapidly rolling westward. And the closer the border became, which the enemy had crossed three years ago, the more fiercely, it seemed, he clung to every inch of our land with the stubbornness of the doomed.

However, this was understandable — Belarus opened access to East Prussia. It was no coincidence that Hitler ordered the garrisons of major cities, including Mogilev and Grodno, to defend them "at any cost." Thus, the advance of our troops was not easy.

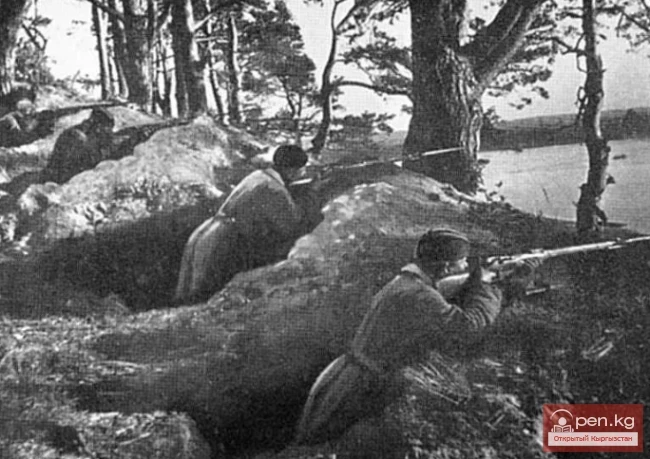

...On a July evening, the battalion reached the Neman. No matter how hastily the enemy retreated, he managed to blow up the bridges behind him.

It was ordered to rest for now, without revealing themselves unnecessarily. The soldiers, pleased that the kitchen had not been late this time, quietly chatted while scraping their mess kits. They discussed what our command would decide: to cross the river on the fly, like the Dnieper, or would they wait for the sapper unit to establish a crossing.

As usual, there were some "strategists" with arguments for both tactics. But Sukhin, listening to the soldiers' conversation, understood: deep down, everyone hoped for the latter option. It promised at least a small respite.

No matter what, they had done well at the Dnieper. In broad daylight, under fire, the platoon managed to create a passage through the barbed wire, drive the enemy out of the front line trenches, and hold that corridor until the entire regiment crossed. But no one wanted to tempt fate a second time. That corridor had come at a high cost. Many comrades had forever remained in the waters of the Dnieper and in the reed marshes.

Sukhin was pulled from his thoughts by a quiet shout from a sentry and the voice of a messenger: "Platoon commander — to the company commander!"

In the hastily dug-out of the company commander in the slope of the same hollow where the platoon had taken cover, a wick was already smoking in a shell casing. At the flap of the raincoat covering the entrance, the flame flickered desperately.

— Comrade Captain, Lieutenant Sukhin...— he began formally, but the company commander nodded briefly — as if to say it was unnecessary — and covered the trembling flame with his hands.

— Sit down,— he motioned to an empty ammunition crate. — Here’s the deal, Semen Zakharovich,— he raised his inflamed eyes, weary from lack of sleep, to Sukhin...

The battalion knew, and Sukhin knew it too — when sending people on a serious mission, the captain avoided a formal tone. Perhaps it was a remnant of his pre-war habit as a factory engineer, or maybe he simply understood that warmth was more necessary for a person in such cases. Many years later, Sukhin heard a line in a war poem on the radio: "Those words of order sounded like a plea," and immediately the image of his company commander came to mind.

The assignment turned out to be familiar yet quite dangerous. This time, the platoon was to cross the Neman at dawn using makeshift means, capture a bridgehead on the other side, and try to hold it as long as possible. A platoon under Lieutenant Zholud was being sent to support them.

— Hold out for at least a day,— the company commander concluded.

He did not say why exactly a day was needed. Sukhin thought he might not know himself. Over three years on the front, he had learned that even captains were not always informed of the details of operations. In any case, he did not want to pry. A day was a day. They began to clarify the action plan.

The captain liked this not-so-young — nearly forty — lieutenant in his platoon commander’s role.

Although, what did he know about him? Little, if speaking about his biography. In the past — a district financial inspector. He began the war as a communist (he submitted his application to the party after receiving a draft notice) and as a sergeant near Kaluga. He was wounded.

After the hospital — courses for company political instructors, assignment to an evacuation battalion. He requested to go to the front, and was transferred here from the reserve of the front. Somewhere in a Kyrgyz village, his wife remained with four children.

He got to know him much better by how this taciturn man with slightly ironic eyes, essentially a purely civilian person, fought. This was evidenced by the highly respected soldier's medal "For Courage" and the order he received when he was already an officer.

It was hard to send such a person on a deadly dangerous mission again. After all, four children — that’s no joke. And there were certainly younger platoon commanders, single, nimble men. But the company commander could not help but understand who would cope better with this task. And the war had taught him that sometimes the best compassion is sober calculation and strict discipline.

Sukhin returned late in the evening. Ahead, over the river, illumination rockets occasionally hung — the fascists were watching the river. After the rockets, the night became even darker. Sukhin had to hold onto the branches of the willows, stumbling on the hummocks and slippery roots wet with night dew.

...The conversations suddenly fell silent. The soldiers shifted, giving their commander a place. In their eyes, fixed on him, one question was read: what did the company commander say? Sukhin did not keep them in suspense and laid out the task.

By morning, a path to the shore had been dug. They pushed logs into the water and silently stepped into it, dissolving in the gray, patchy fog. The day of July 14 was beginning.

For a while, the fog was helpful, but it could not be a savior forever. About forty meters from their shore, the fascists, who had been on alert all night, finally noticed them. The dawn silence was torn apart by machine-gun fire. Fountains danced on the water.

Several hands slipped from the logs and disappeared under the water. The wounded tried to hold on. Sukhin himself was lightly hit. Looking back, he noticed how the regiment's telephone operator, Osinny, was trying with all his might not to fall behind him, not to get lost in the fog.

But here was the shore. They quickly bandaged themselves. Sukhin counted the available forces. Six remained from his platoon, and Lieutenant Zholud from the neighboring platoon, who had somehow ended up without his own platoon. In total, eight. Not many, but it was possible to fight and accomplish the task. They spread out and rushed up the slope overgrown with sedge. Sheremet, the youngest among them, covered them with machine-gun fire from the flank.

At first, the Germans did not pay them much attention. More concerned about the possibility that the main forces would follow the first landing, they diligently tore the fog over the river to shreds with a leaden rain. But realizing that the crossing had been disrupted for now, they shifted their fire to the daring soldiers. They had to lie down and start digging in.

Sukhin assessed the situation. The reclaimed area was no wider than fifty meters along the front and the same in depth to the shore.

Now this patch of swampy, yet familiar land near the village with the wonderful name Lunno was their main front on the entire 2nd Belarusian front. They had to cling to it with their teeth until the regiment established, as he believed, a crossing.

And only those who were supposed to know knew that morning that on the enemy's bank of the Neman, a desperate platoon was drawing attention to itself to give the regiment the opportunity to successfully cross the river elsewhere and strike the enemy in the rear. Yes, cunning in war sometimes demanded a high price.

The lines of the combat report from the command preserved for us a sparse chronicle of that day. In the very first hours, eight enemy counterattacks were repelled.

Enraged fascists, eager to deal with the landing party, spared neither strength nor fire for this purpose. About 150 fascists went against Sukhin's group. But leaving half before the trenches of the brave soldiers, the thinning chain retreated.

And the situation of the defenders of the bridgehead was becoming critical. Ammunition was running low. Sukhin decided on a bold step. He took Sheremet with him — young, agile, and most importantly, he knew the machine gun.

...In the darkness, they descended to the water and, under the cliff, listening intently, crawled toward the enemy positions. As agreed, the remaining soldiers, as if plotting something, began to fire sparingly at the enemy's left flank, where their machine gunner was lying. He responded with long bursts. "If only the fool hadn't shot all the belts," Sukhin worried.

Now they could distinguish the silhouette behind the gun belching fire. Sheremet accurately determined the moment when the fascist ran out of belt and reached for a new one. Two knives did their job. Seizing the machine gun and boxes, they, no longer hiding, rushed to the cliff. Delayed tracer rounds traced the air above their heads.

The fascists launched a new attack at dawn.

— Comrade Lieutenant,— Sergeant Kalinin nudged the dozing Sukhin on the shoulder and nodded over the parapet. — Look what the bastards have come up with. They must have decided to throw us into the Neman.

The Germans were advancing in several waves, leisurely, in full view. Short commands were heard. For the fullness of the psychological attack, only the sound of drums and fluttering standards were missing.

Sukhin involuntarily recalled the exhausting battles in the Moscow region, where their recently arrived division from Frunze, still unscathed, held the defense. Back then, the enemy had approached their positions with roughly the same audacity.

— Damn it,— he slammed his fist on the broken apparatus in frustration. — It would be good to give the mortarmen a correction and cover those bastards at once.

— Instead of dreaming about mortars, you should go and borrow a machine gun from the fascists like our Sheremet and the lieutenant,— Solopenko couldn't help but jab at the telephone operator for his misfortune.

— Enough of the chatter,— Sukhin interrupted before an argument could start. — Fire only on my command.

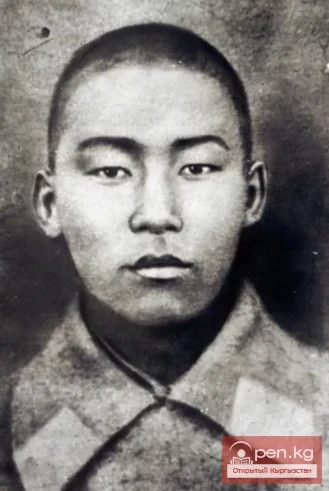

Letting the first wave approach within a hundred meters, they opened fire with all their few weapons. Sukhin noted with satisfaction how the deep voice of the trophy machine gun stood out in the roar. But behind the thinning line, the next wave was rolling in. And just then, as if choking on half a word, the machine gun fell silent. Sukhin turned around; Sheremet had slumped lifelessly by the machine gun. Shouting, "Grenades ready!" he rushed to the flank of the silent machine gun.

The second day of their defense began when they heard the sounds of an approaching large battle and noticed frantic movements at the enemy's positions. At first, they did not understand why the prolonged "Hooray!" was coming not from the river, where, according to their calculations, the regiment should be, but from behind the enemy's back.

...The decree awarding all seven the title of Hero of the Soviet Union (Lieutenant Zholud is not mentioned in the decree — his participation in the operation was reported by Sukhin and his combat comrades to the red scouts from Lunno) will be issued immediately after the Victory. But by May 9, only three of them will survive: Sergeant Kalinin, Junior Sergeant Osinny, and Sukhin, who by that time had become a senior lieutenant, commanding a company in the same battalion. However, Semen Zakharovich will receive the news of Victory in a hospital near Berlin, having been wounded in both legs.

After the war, he returned home to Kyrgyzstan. The Sukhin family welcomed a second son — Alexander, now an employee of the Tomsk Research Institute of Automation and Electromechanics. There, in Tomsk, Sukhin the elder managed to babysit his grandson, also named Semen in his honor. It is also in Tomsk that Semen Zakharovich was buried in 1971.

And in the village of Lunno, streets named after the Heroes remain. The local secondary school is named after the Komsomol member Sheremet. Their portraits are prominently displayed at the entrance to the village. There they all are — young.

L. KONDRASHEVSKY