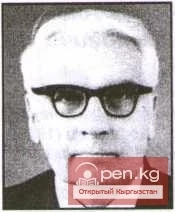

Hero of the Soviet Union Dmitry Nikolayevich Pichugin

Dmitry Nikolayevich Pichugin was born in 1907 in the village of Kolyvan, Kolyvansky District, Novosibirsk Region, in a peasant family. In 1937, he moved with his family to Kyrgyzstan. He was Russian. A member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Lieutenant. Commander of a reconnaissance platoon.

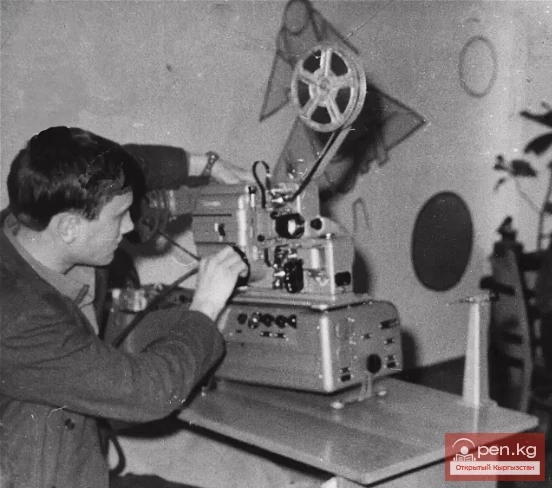

He began his combat path in 1939 during the war with the White Finns. After demobilization, he returned to Kyrgyzstan and worked as a cinema technician in the Alamedin District.

With the onset of the Great Patriotic War, he went to the front. In the winter of 1941, he became a scout. He participated in battles near Moscow. As part of the 2nd Belarusian Front, he took part in the liberation of Belarus. The brave scout completed his combat path in Berlin.

The Motherland highly appreciated the merits of Dmitry Nikolayevich Pichugin. For his military feats, he was awarded the Orders of the Patriotic War II class, the Red Star, and medals. On March 24, 1945, he was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

During the war, he sustained four wounds. He died in 1947 after a prolonged and serious illness. He was buried in the city of Osh.

THE FEAT OF A SCOUT

Dmitry Nikolayevich Pichugin was born in 1907 and died in 1947. He was given only forty years to live, but what a strain of strength, will, and courage it demanded from him! As I leafed through documents in the archive, I thought that perhaps the most peaceful, and maybe the happiest year for him was 1940. He had just been demobilized from the army — the battles with the White Finns were behind him — he was offered a job as a cinema technician, which, at that time, was one of the most prestigious professions, and Dmitry Nikolayevich must have felt a sense of satisfaction that everything was going well, that he was doing what he loved.

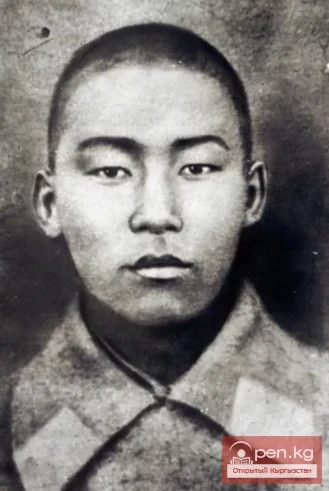

I gaze at the photograph — what was he like, this handsome, stern-looking man? What was he planning for that Sunday when the war began? How did he envision his life? Now, there is no way to find out. Because the war began, and everything that was thought and dreamed was pushed to the background, giving way to thoughts of the Motherland, which had fallen into trouble.

He showed villagers films that became classics of Soviet cinema, which were still freshly shot, beautiful in their novelty, joked, laughed, and although he sang the song "If Tomorrow Is War...", he did not want to believe that it could happen.

But the war began. Suddenly, the bright, peaceful life filled with an endless stream of important and unimportant, difficult and easy, sad and joyful affairs and events was cut short. It seemed especially incredible since nothing had changed in nature: the sun still shone, the birds sang, and the grasses smelled fragrant. Pichugin walked to the military enlistment office and felt acutely how he was becoming alienated from the tranquility and softness of nature, which had seemed eternal, constant, and reliable just yesterday. Now he was stronger than it, because its constancy and eternity depended on him.

The war began far from here, from the fields warmed by the hot June sun, from the trees covered with unripe fruits, from the icy, gently murmuring water flowing over the stony bed of the irrigation ditches, but for Kyrgyzstan, it began at the same hour and minute when the enemy brutally and cruelly broke through the border of the native country. As everywhere, the men of Kyrgyzstan, whose strength and power could become a reliable shield for the Motherland, hurried to finish the work they had started in the fields and at home, soothingly smiled at their wives, tenderly caressed their children with a sense of guilt, fearing to even think that they might be left orphans, that they might forget the harsh tenderness of their father's hand — they needed to go to war, they needed to win, they needed to return the bright, peaceful colors to nature.

Pichugin did not spare himself at the front. And although he was only lightly wounded (but four times!), I think, I am sure that the war shortened his years. Had it not been for the war, he would have definitely lived longer; he could have lived longer.

In the winter of 1941, Dmitry Pichugin became a scout. Going behind enemy lines, into the enemy's rear, capturing "prisoners," obtaining valuable documents, and if necessary, engaging in combat — this became his main task in the war. I try to imagine these frequent forays behind enemy lines. Surely, Dmitry Nikolayevich was scared, scared every time he went into the enemy's rear. An ordinary person could not help but fear an encounter with the enemy, especially since it was not in open combat, and there were no allies on the left, right, or behind to cover or assist them; the handful of scouts had to do everything and decide everything themselves. But stronger than fear was duty, stronger than the desire to live was the desire to defeat the enemy at all costs — this is where the man, voluntarily and consciously going into the enemy's rear and solving his difficult military task, drew strength and firmness. By the beginning of the war, Dmitry Nikolayevich was a mature man, he knew the value of words, was used to judging people by their deeds, and most importantly, he knew how to hold himself accountable with all seriousness. Thus, he had been preparing for his main feat his entire previous life.

Pichugin had already been wounded three times, had been in hospitals three times, but the confidence that the war would not destroy him, would not break him, not only did not weaken in him, but, on the contrary, grew stronger. Now, having learned all the subtleties of reconnaissance, having endured and experienced so much, knowing the true value of good and evil, he simply could not die.

In 1943, Dmitry Nikolayevich Pichugin wrote a statement requesting to be accepted as a member of the VKP(b). He had fully tasted the bitter, smoky air of war, and if he had to perish, contrary to common sense — can death ever be meaningful? — he wanted to die as a communist. Thousands of kilometers were traversed by Dmitry Nikolayevich Pichugin, the Motherland marked his military path with the Orders of the Patriotic War II class and the Red Star, but his main feat was still ahead.

Our troops approached the Dnieper, our river, which Hitler intended to turn into an insurmountable water barrier. The fascists placed great bets on this line, boasting to the whole world that the right bank of the Dnieper was firmly fortified with equipment, weapons, and combat power. They considered everything except for the spirit of the Soviet warriors liberating their Motherland.

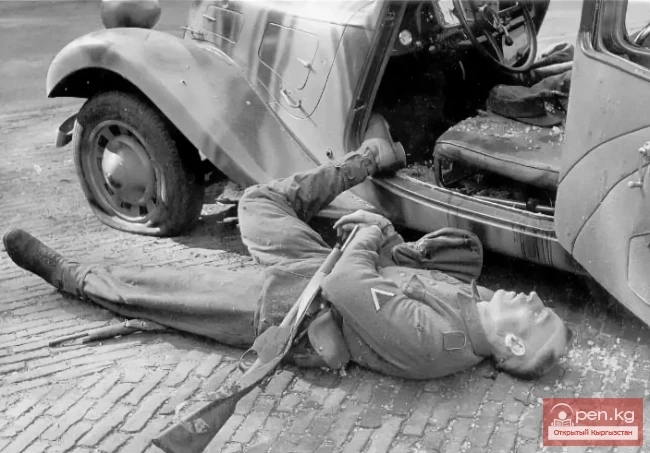

To carry out the order — to scout the enemy's forces and defenses on the right bank of the Dnieper — Lieutenant Pichugin set off at four o'clock in the morning on June 26, 1944. It was already dawn, and the river was well visible to the enemy, but he successfully swam across the Dnieper and entered the village of Pleshch, so small that the fascists did not even deem it worthy of a post. His comrades also crossed to the other side of the Dnieper. All — intact, all — unharmed. The first success invigorated them. They moved along the Shklov-Mogilev highway. A pre-dawn silence hung over the land. They walked as the war had taught them: quietly, cautiously, trying not to snap a branch under the weight of their steps, not to let a stone slip from under their boots.

Suddenly, in the silence, a monotonous sound of engines became distinctly audible. The scouts dashed off the road and lay down.

Three cars were moving along the highway towards the Dnieper. Lieutenant Pichugin knew that in such a situation, the outcome of the battle largely depended on the element of surprise, on the scouts' ability to strike the enemy quickly and accurately so that they would not have time to react. Officers were surely riding in the cars, and therefore they needed to capture them at all costs. With aimed fire, they shot down the rear car, and while the other two were deciding what to do — save themselves or help the wounded — the scouts twisted the arms of the Nazi officers, seized the documents, and were gone.

This is the most general outline of that battle. The most general, devoid of any details and specifics that can no longer be restored because the main hero of it — Dmitry Nikolayevich Pichugin — is no longer alive. And why invent? No fiction can replace the true story, for it is well known that what seems unfrightening in fiction is full of genuine drama in life. For me, for example, the very possibility of attacking that third car (in view of other enemy vehicles, whose passengers are armed) seems incredible. But it happened and brought tangible results! What kind of heroism must people possess to dare to engage in such a battle...

It later turned out that the captured documents were of particular importance: in the briefcase were papers from the headquarters of one of the Hitlerite divisions and a map with markings of strongholds. The officers revealed some information.

From the award sheet for D. N. Pichugin: "With his reconnaissance, Lieutenant Pichugin ensured the rapid crossing of troops across the Dnieper and thus contributed to the swift advance against the enemy on the other side of the Dnieper. Comrade Pichugin is worthy of the highest state award — the title of Hero of the Soviet Union."

The commander of the 44th Rifle Regiment recommended Lieutenant Pichugin for the award, then the award sheet bore the signature of the commander of the 42nd Smolensk Rifle Division, and then it was signed by the commander of the 69th Rifle Corps... And at each stage, a note was made: "Lieutenant Pichugin is worthy of the title of Hero of the Soviet Union."

By decree of March 24, 1945, Dmitry Nikolayevich Pichugin was awarded this high title and presented with the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star medal.

But while the documents were going through their due process, while the feat of the lieutenant was being analyzed at each level of command, he continued to go on reconnaissance, participated in battles — because he needed to reach Berlin, he needed to see with his own eyes the last agony of the war that had stolen so many peaceful days and nights from him. He reached Berlin. I do not know if he signed the walls of the Reichstag or not. Probably, he did sign: let his name, that of Lieutenant Pichugin, be on this last page of the war.

He was given only forty years to live. He managed to live them with dignity.

L. ZHOLMUHAMEDOVA