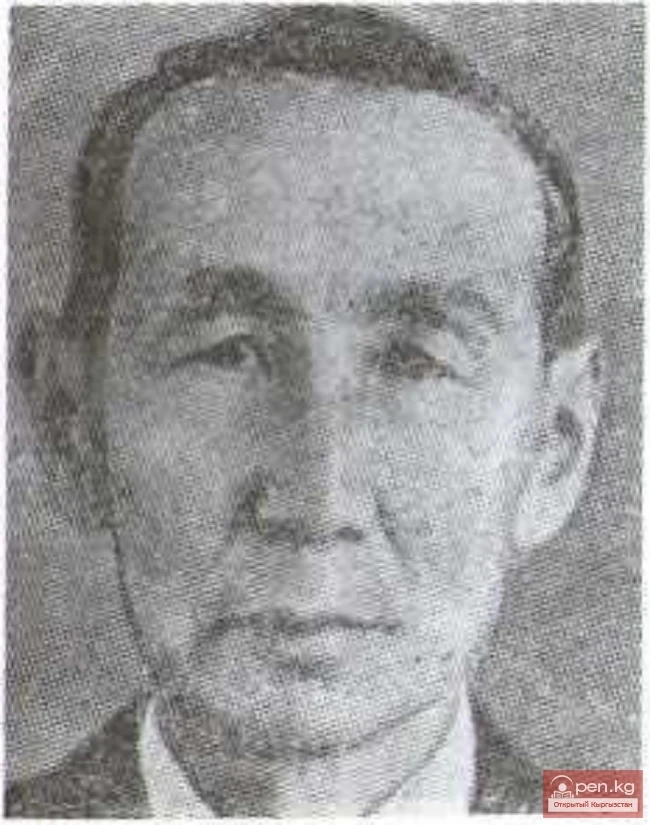

Hero of the Soviet Union Belyandra Vasily Yakovlevich

Vasily Yakovlevich Belyandra was born in 1914 in the village of Dosovskoye, Kutubuksky District, Kostanay Region. At the age of sixteen, he moved with his parents to Kyrgyzstan, to the village of Buruldai in the Kemin District. He was Russian. He worked as a blacksmith and later as a combine harvester operator in a collective farm. In August 1941, he was drafted into the Soviet Army.

His biography began in the harsh defensive battles on the Don and Stalingrad fronts. On November 17, 1943, for his displayed courage in an offensive battle during the crossing of the Dnieper, he was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union for his military skill.

He was awarded two Orders of the Red Star, the Order of the Red Banner, the Order of the Patriotic War 1st class, the Order of Alexander Nevsky, and several medals. Vasily Yakovlevich participated in the Victory Parade of 1945. After the war, the hero returned to Kyrgyzstan for peaceful labor.

He died in 1967.

In the village of Buruldai, Kemin District of the Kyrgyz SSR, one of the streets is named after Vasily Yakovlevich Belyandra.

ON THE DNEPROVSKY CLIFFS

September 1943. The Red Army was swiftly advancing towards the Dnieper. Ahead of the infantry raced the T-34 tanks.

On the turrets, the long-awaited words were painted in white: "Let's take the Dnieper!", "Forward, to Kiev!".

As they retreated, the fascists burned the villages along the Dnieper. Only the ruins of brick houses were visible here and there, with bare chimney stacks reaching up.

With the advance units of the 23rd Motorized Rifle Brigade moved a platoon commanded by Junior Lieutenant Vasily Belyandra. An experienced warrior, he had already fought in the Don steppes and in Stalingrad. He had tasted the bitterness of the summer retreat in 1942, was wounded, and lay in the hospital.

Now Vasily, like all the soldiers, was filled with joyful anticipation of meeting the Dnieper. The wheel of war had turned sharply. Now the fascists could not change the course of events. Soviet soldiers — both commanders and privates — had learned much during these difficult years of trials — primarily how to strike a seasoned and strong enemy. Now our path was only in one direction — westward.

Did he think, the son of a hereditary farmer and himself a peasant, that he would have to master the complex science of war in a short time? Vasily was used to working in the forge, easily handling a heavy hammer. And when new machinery arrived in their Kyrgyz village of Buruldai, he couldn't resist sitting at the controls of a combine harvester. Vasily drove his obedient machine across the wide Kemin fields, harvesting grain, and it seemed there was no greater happiness than filling the granaries with golden grain.

The peaceful clear sky in the distant land, the snowy mountains of Ala-Too in the barely noticeable haze — all this was left behind, in that life which was roughly plowed over by the war imposed on our people.

He also received the terrible news in the field. And although it was a day off, all of them, the mechanics, were working, each not wanting to fall behind the others.

— Wait a bit, — said the major to him. — Your turn will come, Vasily Yakovlevich. But right now, the combat task is different — to completely harvest the crop.

Where did the strength come from! And then he looked back at the harvested field, kissed the combine, as if saying goodbye to a close friend for a long time. When would he sit at the controls again, and would he even have to? Reports from distant fronts were discouraging, and the postmen were already delivering death notices to homes.

Now his companion was the rifle. The combine operator had strong hands and excellent eyesight. A considerable number of fascists had been killed by Belyandra's accurate bullet.

- In the hospital, when his condition began to improve and he was preparing to be discharged to return to his company, he was told that he was being sent to a military school.

— You see, there is a shortage of commanders. And you are already a seasoned fighter, you have smelled enough gunpowder. You are just right for a platoon! — the captain who came to the hospital persuaded Vasily.

Convincing was one thing. Belyandra himself understood that the matter was decided and there would be no long objections. In the end, they would order him. And you — a soldier, you know military discipline.

Now, going towards the Dnieper, he thought that he was generally lucky. He ended up in a brigade commanded by the renowned commander Colonel Golovachev, a tough man. He didn't say much, demanded more, but treated his subordinates with understanding.

— With such a father, any task can be solved, — the soldiers said. And the task now before them was one — to reach the Dnieper and cross it as quickly as possible, before the fascists recovered from the powerful tank blows of our advancing units.

That morning, a armored personnel carrier caught up with them on the march. A short, stocky man in a raincoat got out. The soldiers recognized him: the commander.

— Whose are you? What unit?

— We are Golovachev's. The 23rd Motorized Rifle.

— Well, I see you are eager to get to the Dnieper. Come on, guys, hurry up, or the neighbors might overtake you.

They reached the Dnieper near the village of Veliky Bukrin. The day was drawing to a close on September 23. Vasily took off his helmet, scooped up some water — and indeed, the Dnieper water was delicious.

— On the other side, it will be even sweeter, — said Golovachev, who had approached.

He gathered the commanders. They were deciding how to cross.

- He sighed heavily.

— There is nothing. The means of transport have lagged behind. We will have to stick around here now. The Dnieper is wide; you can't just jump across.

Golovachev pressed his already thin lips together.

— I see it is wide. But we need to cross now, immediately. Everyone looked at the high cliffs over there, on the right bank. And on the heights, of course, there were machine guns. So the enemy would let you through, just wait!

There was no time to think. Belyandra ordered the soldiers to look for boats and to tie logs into rafts.

— The eyes are afraid, but the hands are doing, — he said, as he always liked to say when it was hard, but he had to overcome himself.

It was drizzling, the Dnieper was rolling in waves. And the soldiers were already crafting rafts. Someone found a half-submerged boat — Belyandra was delighted: this was just what they needed.

— Come on, Mikhail, bring the machine gun here, — he ordered Sergeant Vdovenko. — Well, let's go!

He pushed off from the shore with a pole and — forward. He looked: in the darkness, here and there, soldiers were floating on makeshift rafts — the platoon began the crossing.

But the fascists were waiting for them. They had not reached the middle of the river when the shelling began. Shells and mines tore through the air and water, machine guns rattled, and they kept floating forward, and it seemed there was no end to this crossing.

Vasily did not know how much time had passed when the shore appeared. He hurried, jumped out of the boat, barely feeling the bottom, and rushed onto the shore. After catching his breath, he looked around: nearby, Mikhail Vdovenko's machine gun had already started firing, and they were being supported by fire from the left bank.

— Hooray! Forward! Follow me! — in the roar of gunfire, Belyandra seemed not to hear his own voice, but he felt — the soldiers rose up behind their commander and went into the attack.

No, the fascists clearly did not expect such audacity. The platoon burst into the northwestern outskirts of the village of Traktomirovka. A small height dominated the area. Belyandra immediately ordered to outflank the enemy and bombard them with grenades from the rear. The fight did not last long — they charged with bayonets, driving the fascists out of their trenches.

Belyandra looked around. Things seemed to be going well; moreover, the Germans had abandoned four vehicles with ammunition.

Until the main forces arrived, they needed to organize defense and contact the neighbors: "What do they have?"

In the morning, the enemy did not keep them waiting. Tanks, and under their cover, infantry, moved towards the height occupied by the platoon. It began! The fascists were met with a hail of fire, burning tanks smoked. They retreated, but then again and again attacked the platoon's positions and rolled back.

Belyandra's platoon withstood seven counterattacks on the very first day of fighting on the right bank — and the junior lieutenant invariably appeared in the most dangerous areas.

They held on for a day, then a second, and a third. They held on, although it was unbearable. Belyandra, running across the trench, kept asking: "Are you alive, brothers? Hold on, just a little longer."

Again the enemy rose to attack. But why was the machine gun silent over there, on the left flank? Vasily rushed there. The number two was lying on a box of ammunition — he had been struck by a fragment. The commander of the crew was trying to rise — he couldn't, he was wounded. And the fascists were getting closer and closer. Just hurry, just run.

He made it in time. There was no time to aim — he shot directly, at close range. The Germans lay down and began to crawl back.

The company commander stood up to his full height: "Follow me! Forward..." He didn't finish, fell — and the soldiers hesitated for a moment.

— Forward — it was already Vasily who stepped out of the trench, waved his hand — Forward!

…By evening, Golovachev appeared in the trench.

— Where is the company commander?

— Wounded, Comrade Colonel. I took command.

— Well done! But keep in mind — hold on to the last.

He embraced Belyandra; this stern man was not used to showing his feelings.

— Hold on. I ask you. Just a little longer.

The battle was quieting down. Clumsily, with their turrets twisted to the side, two "Tigers" stood before the height, frozen in their heavy movement. Three self-propelled guns also did not move. Dozens of fascists found their death here, trying to throw Vasily Belyandra's platoon into the waters of the Dnieper. And these men, covered in dust, bloodied, utterly exhausted, were now sleeping soundly, as after the hardest work. They, of course, did not see that it was beginning to dawn, and did not hear how our stormtroopers roared westward, and where the mighty waves of the wide Dnieper flowed, a ferry crossing had already been established, and tanks with the inscriptions on their turrets "Forward, to Kiev!" were going one after another to expand the bridgehead and finally secure themselves on the right bank.

Vasily Yakovlevich Belyandra learned that he had been awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union later, two months later — in the hospital. He did not get to enter Kiev; he was seriously wounded on September 30. But later, catching up with his unit after recovering, he managed to visit the city for which he had fought to the death on that nameless height near the village of Traktomirovka.

Just a few hours, because the Hero was called by new front roads, because the war was not over, and Berlin was ahead.

He returned to his native village — and took up his usual work again. He had long awaited this hour, bringing it closer in the smoking Stalingrad, on the steep banks of the Dnieper. And always, while fighting through Russian and Ukrainian villages, Vasily Belyandra remembered his native Kyrgyz village of Buruldai. The village where, in his memory, a wide street in silver poplars is now named after the Hero.

V. Niksdorf