Search for Father

The telegram reached Ak-Olen immediately, and Aiganish-ezhe began to prepare for the journey. She put on her best dress, tied a scarf tightly, the most beautiful kerchief.

The bus was moving quickly, and Issyk-Kul was gradually left behind, only the sun was blinding her eyes painfully, to tears. The telegram was from Klara, the daughter of her brother Omor: tomorrow, on July 31st, Aiganish Jumayeva is invited to meet with President Akayev.

In the village and the Kok-Moynok state farm, everyone knows Aiganish-ezhe. For almost forty years, until her retirement, she managed the paramedic and midwifery station. How many people she healed, how many births she assisted! But in Bishkek, in the hall on the seventh floor of the building where the Cabinet of Ministers is located, no one knew her. And she knew no one. So she sat at a small table in the left row, by the window, next to Klara and her grandson Ermek.

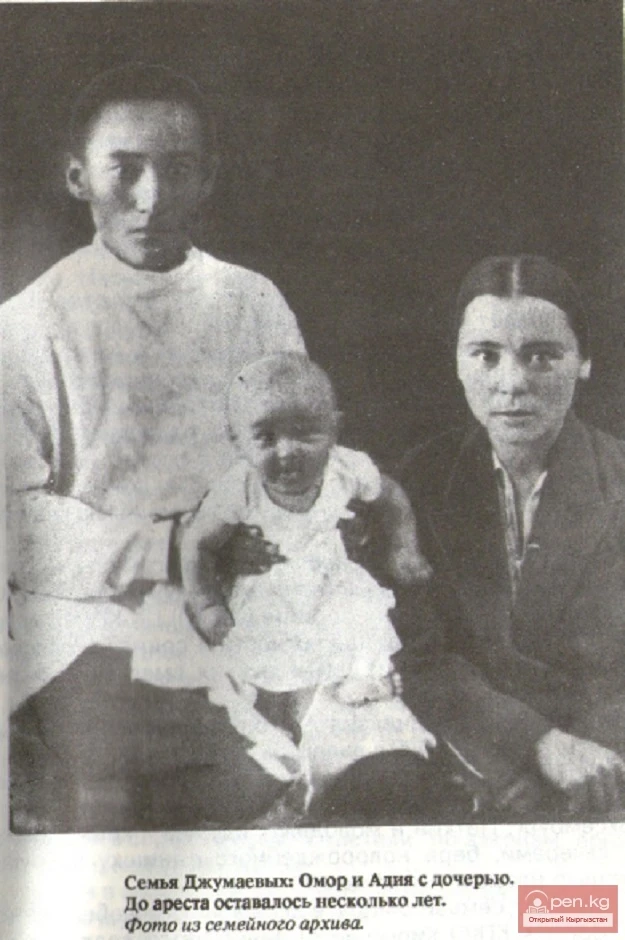

She recognized the papers of Omor, which he and his wife Adiya had hidden in a chest in the barn after a search in March thirty-eight, and then took with them. She remembered how they left Frunze in fear - they were immediately ordered to vacate their apartment.

As they traveled to their native Jumayev lands, to Issyk-Kul: Adiya with two small children and she. They traveled at night on transfers and hid in the houses of kind people during the day.

Klara took out these papers, two photographs of her father - nothing more, and placed them on the table. For her, her father remained in memory like this: looking seriously into the lens. But Aiganish remembered her older brother as joyful and cheerful. The windows of the house where her brother was given an apartment overlooked Oak Park. The snow had almost melted by then, and the holiday was approaching. On March 8th, Omor always gave small gifts to his wife and sister, brought flowers. Adiya sat at home, nursing their three-month-old son, while Aiganish was finishing her medical school.

Omor was arrested at work - on March 2nd, in the morning, around eleven. The deputy head of the department of leading party organs (ORPO) of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (b) of Kyrgyzstan was accused of belonging to the social-Turanian party. This was one of the gravest, deadly sins in Kyrgyzstan in the 30s and 40s.

A worker from the Central Asian State University, a member of the Communist Party (b) since twenty-seven, Omor Jumayev blindly believed in the victory of the world revolution. Rosa, Klara, Mik - such names he gave to his daughters and son. In honor of Luxembourg, Zetkin, and the youth marching towards communism. But in the evenings, taking his newborn son in his arms, he quietly called him Misha.

When a deadly threat loomed over Omor's family on the day of his arrest, when he was removed from his position at the bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (b) of Kyrgyzstan and taken out of the candidate members of the Central Committee, his stepfather Aaly adopted his adopted grandson. Not yet able to walk or talk, left without a father, Mik became Mikhail. Mikhail Aliyevich Aliyev graduated from the agronomy faculty of the agricultural institute, lives and works in the Issyk-Kul village of Jylu-Bulak.

... Trouble came to apartment N 5 of house N 70 on Pushkin Street. Klara was approaching her third year. Swaddling her son, Adiya ran to the gray building of the Central Committee...

Aiganish-ezhe sighed heavily... She must definitely go with Klara to their old house on Pushkin. They say there are now editorial offices, but maybe they will allow them to see their apartment?

Klara seems worried too. And how many people! She heard downstairs in the reception area, while they waited - people came from Osh, from Talas, Naryn, from Almaty...

Until the last minute, neither Aiganish-ezhe nor Klara Omorovna knew why they were invited to meet with the President. Perhaps they suspected.

The day before, anxious, Klara Omorovna came to the editorial office.

- I received a call today from the KGB. They invite me to a meeting. Do you know why?

I didn’t know. But somehow, in one of our conversations, she had already mentioned that in the rehabilitation certificate for her father, which she and her mother received in October fifty-seven, there was a date for the execution of the sentence.

The date, which was clearly readable on the copies of the accusatory conclusions found among the remains in the last days of the excavations, was one digit less.

Only a few knew about this for now.

For nineteen years, Adiya Tokzhanova, Klara's mother, searched for her husband. She tried to find out at least something about his fate. Where did she not turn! And not after March fifty-six - BEFORE. "The sentence is final and not subject to appeal," they replied to her in another official document from Moscow in forty-one. They answered "by the laws" of the time - sharply, unequivocally.

Where did a small rural teacher get so much faith and courage?

Klara remembers her father vaguely. But she knows quite a bit about him. From her mother, from Aiganish-ezhe: memory cannot be shot.

How did they live, the children of "enemies of the people"?

In fifty-four, after finishing the tenth grade, Klara Jumayeva was taking entrance exams. She wanted to go to Moscow, to the university, to the law faculty. She believed that only by becoming a lawyer could she prove her father's innocence and find at least some information about him.

She took the exams in Frunze, at boarding school N 5, the only one at that time where teaching was conducted in Kyrgyz.

Klara Jumayeva:

Students from all over the republic gathered for the exams. One boy was doing particularly well; he was applying, if I’m not mistaken, to the geological exploration institute.

And here is the next exam - in history... The door opens, and the boy who decided to become a geologist comes out into the corridor. Without saying a word, he walks to the window. He stands, turning away from us, holding his head in his hands. He stands silently, breathing heavily, biting his lips. And then he utters dully: "He said my father is a traitor." And he cried.

I enter the classroom. The same examiner asks the first questions: who are your parents, what do they do?

I answered about my father: he was accused and convicted, no contact with him. The examiner began to inquire: what was he convicted for? Our dialogue continued.

I: - I don’t know, he was accused and that’s it!

He: - Didn’t your mother tell you?

I: - She told me he is innocent, everyone says he is innocent!

He: - If he were innocent, they wouldn’t have convicted him.

I: - It was a mistake.

He: - What mistake?!

I: - If you know, tell me! What do you want from me? Here! I passed the constitution with a five. Parents are not responsible for their children in such cases, and children are not responsible for their fathers! But he is innocent!

He: - How can he be innocent?!

I (already shouting): Tell me - for what?! He is innocent! What do you want from me?!

I stand up, grab the green cloth tablecloth, lift the table, take the glass inkpot. I don’t need this

Moscow, I can not go!

A Russian man, a representative from Moscow, glanced at us. Now he stood up, approached me, took me by the shoulders, and sat me next to him. No one in the room uttered a word... Then the Muscovite said something to my examiner in a white, fashionable chintz suit, quietly but firmly.

My documents were processed, but of course, not at Moscow State University.

Klara did not become a lawyer.

She worked at a factory, graduated from the economic faculty of the university, worked as a flight attendant. She was one of the first to fly to Moscow on the Il-18. She raised a daughter.

... Together with Klara Omorovna, we look at the second volume of the Kyrgyz Soviet Encyclopedia. Here it is, the photograph of her examiner. And here is the article about him: at thirty-six - Doctor of Historical Sciences, at thirty-seven - Professor, at forty - Academician of the Academy of Sciences of the republic. He became an academician in that year, fifty-four, when, feeling complete impunity, he mocked the boys and girls who believed fervently, to the point of frenzy, in their fathers whom they did not know.

No matter what historians in chintz suits say and write.

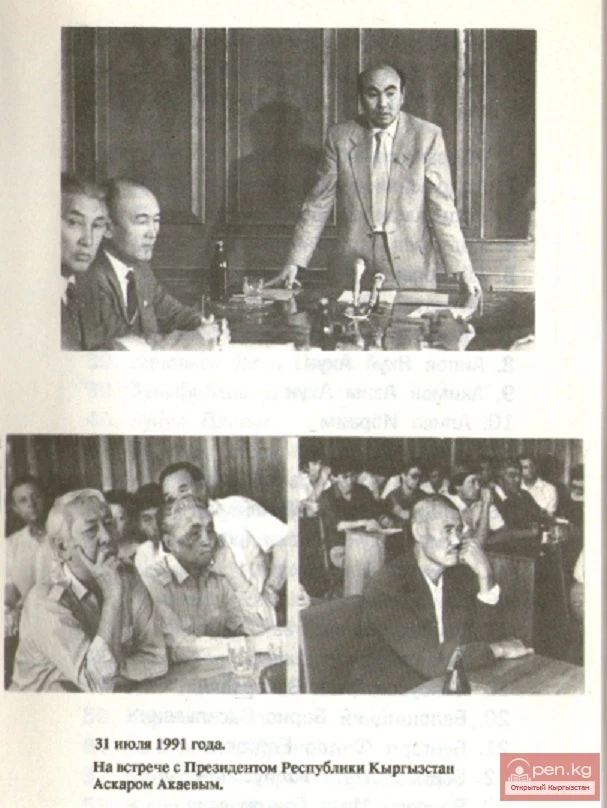

... President Akayev began to read the list.

A personal list, compiled based on the results of work in the archives, of one hundred thirty-seven people, whose remains were discovered at Chon-Tash - the investigation, relying on the data of forensic medical examination, names the figure of one hundred thirty-eight.

Many of the names on this mournful list Klara recognized before she learned to read; they are part of her life. With some wives, her mother, returning from Frunze, carried packages - what could be gathered then from the suddenly impoverished families. The packages were accepted. Although those to whom they were intended were long gone.

For hours, summer and winter, they walked around the building of the NKVD, the city prison, traveled to Pishpek. Holding their breath, straining their hearing, they listened to the roll calls of the prisoners, squinting at the identical gray faces of those who were loaded into freight trains and taken far to the north - to Norilsk, to the Yenisei.

Klara was already familiar with many of the children - shared grief brought them together for years, for decades.

Some she saw for the first time.

Aida Yusupovna Abdrakhmanova.

Larisa Bayalievna Isakieva.

Erkin Kasymovich Tynystanov.

Rafa Imanalievna Aydarbekova.

They did not hide their names, did not change their patronymics and surnames.

They, thousands like them, believed in their fathers, whom they may not have remembered.

They believed in the darkest days. For almost all of them, these came in the years when help and advice were especially needed.

Here they are, in the hall: the daughters of the chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Kyrgyz ASSR Yusup Abdrakhmanov, his successor in this position Bayaly Isakiev, the chairman of the Kyrgyz regional revolutionary committee Imanalay Aydarbekov, the son of the editor of the newspaper "Erkin-Too,” the people's commissar of education, professor Kasym Tynystanov.

Daughters, sons, the brother of the people's commissar of education of the Kyrgyz ASSR Osmonkul Aliyev, the wife of the people's commissar of agriculture of the Kyrgyz SSR Erkin Essenamanov - they approached the microphone, perhaps for the first time, straightening their shoulders and raising their heads: they were not guilty of anything.

They always knew this.

Today, everyone learned about it.

... The President's voice sounded slightly duller than usual: Bulatov Abdrakhman... Goltsov Petr Nikolaevich... Deis Friedrich Gotfridovich... Jamansariev Asanbay, Jienbaev Khasan, Jumayev Omor...

I looked at the small table in the left row, where two women and a little boy were sitting.

Aiganish-ezhe turned to the window, while Klara Omorovna, stunned for a moment, held her head in her hands.

Excerpt from the book "The Secret of Chon-Tash." Published with the author's permission, Regina Khelimskaya.

The Secret of Chon-Tash