The study of the past is good in that one can move freely through time — jumping forward and backward, which is convenient for a stereoscopic perception of life; otherwise, one cannot understand either the pathos of revolutionary transformations or the tragic end of figures about whom we knew almost nothing just recently, and now there is an imperative need to know everything about them. But even now we know too little, as the main archives and investigative files are hidden, in which everything related to the life and activities of the "enemies of the people" was seized upon arrest.

So, after the first congress of the Communist Party of Kyrgyzstan, the nervous atmosphere of universal suspicion intensifies, demagogues run rampant, they stick all sorts of labels on their opponents, still not feeling that the ground is slipping away from under them, that they too are tomorrow's victims of this same rampage of arbitrariness. And now a new "enemy of the people" has been found; it is only necessary to somehow connect him with the already exposed: then everything is in order, the matter is predetermined. To immerse ourselves in the atmosphere of that anxious, dreadful time, let us for a moment try to imagine ourselves as one of the "iron Bolsheviks."

* * *

The daze of the midday heat was interrupted by the high voice of a trumpet. "Alarm! Alarm!" — the regimental trumpet cried with all the power of its brass lungs. Its agitation was transmitted to the people and then to the horses. Cries erupted from all sides, thousands of soldiers' boots and horse hooves thundered on the hard clay. Just a second ago, the parade ground, shining under the bright sun, was now covered with Red Army soldiers.

I threw the straps of the harness over my shoulders, tightened my belt by feel, and, habitually slapping my hand on the holster of my Nagant, ran out of the tent. My bay mare was already spinning around the hitching post, trying to nip the orderly on the shoulder. She saw me immediately and came towards me with a light, dancing step. The orderly let go of the reins. The mare raised her head high and turned sideways to me. I grabbed the saddle horn and leapt into the saddle in one swift motion. The horse immediately broke into a trot, but after going a little way, I reined her in.

— "Halt!" — the command ran from the right flank.

Just a second ago, the shapeless mass of people and animals instantly transformed into a precise formation.

I saw how a commander rode out from the side, surrounded by his staff. From a distance, I noticed that his pale face was covered with large drops of sweat. As soon as my bay mare moved towards the tall stallion, a high, mournful sound was born on the horizon.

The sky tore above my head. The earth trembled, and clods of yellow clay flew up. The steppe was filled with the sound of artillery explosions. An invisible hand seized my breath, and my heart pounded painfully in my chest. I saw the commander’s face, twisted in a scream, and understood faster than I heard:

— "Forward, follow me!"

— "Trot, follow me!" — for some reason I shouted in a high-pitched voice and kicked my bay mare. She jumped, pushing off the ground with all four hooves, and raced after the commander's stallion. The earth roared behind us — a regiment followed us. I caught up with the commander, and he shouted:

— "The Poles are attacking; we have been ordered to counterattack immediately."

We raced through the frequent explosions; I felt that people were falling around and behind me, but I did not look back. Suddenly, everything fell silent; I raised my head and saw the white Poles rushing towards us. Sabers flashed and gold glinted on the square cockades of the enemy hussars. As soon as I pulled my saber from its sheath, I found myself in the thick of the fighting. I shot my Nagant at the chest of a Pole who was in front of me, thrust my saber into the belly of another, and then saw that a saber was raised above my head. Its wide blade was glistening. The saber had turned black with blood. I wanted to block it with my saber, but I couldn't pull it out from the body of the enemy I had struck earlier. I pulled with all my strength and couldn't. The enormous saber slowly descended onto my head; I screamed and tried to rear my mare to shield myself with her head, but the enemy blade came down on my shoulder, and a terrible pain tore through me.

— "Moris! Moris," — I suddenly hear my wife's voice and come to my senses. The kerosene lamp illuminates my wife's white nightgown with tiny flowers. She stands before me, extending a cup:

— "Drink, you were screaming so much; did you see something? Cold water finally drives away the remnants of that terrible dream, and I realize that I am not on the Polish front, but in Frunze, and outside the window, it is not the twentieth year but the thirty-seventh.

— "So what happened?" — Her cool palm touches my forehead, and then I realize that I am drenched in sweat.

— "A Pole almost chopped me down."

— "A Pole?" — she also takes a sip from the cup and laughs, — "So you were in Ukraine again?"

— "Yes, in the Civil War."

There was no sleep; I wanted to smoke. I took cigarettes from the nightstand and lit one.

— "Moris, I'm sorry, this isn't a nighttime conversation, but I see that you've not been yourself lately. You're nervous, swearing, hardly sleeping; has something happened?"

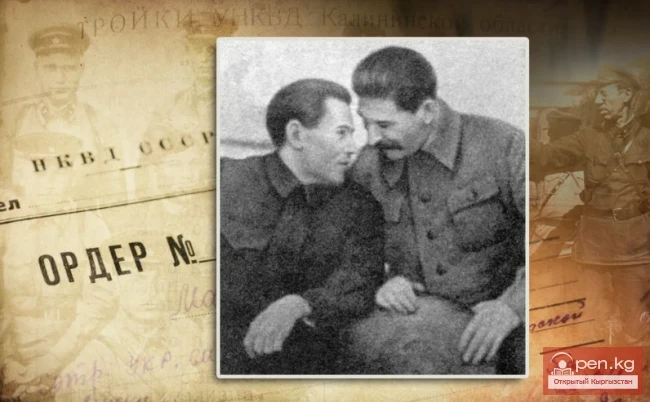

— "Do you remember Stalin's report at the February Plenary?"

— "Of course. And how could this necessary, politically insightful speech of our leader affect your mood? You, the first secretary of the Kyrgyz Regional Committee of the party, are giving all your strength not only to uplift the region, to promote the party line among the masses, but also honestly fighting against the sons of the rich who have infiltrated our ranks. You spend days and nights uprooting the weeds of nationalism and factionalism within the party. What can the party reproach Bolshevik Belotsky for, what?"

— "I also think that I cannot be accused of softness or political shortsightedness. Not a day goes by without me signing sentences for our enemies, the enemies of the Stalin-Lenin party. But yesterday, when this homegrown Chekist came to me with a new list of suspects of aiding the enemies, he looked at me so..."

— "How, how can he look at you, his party leader?" — my wife did not notice how nervously her voice broke.

— "You know that the NKVD has special powers now..."

— "So what?"

The cigarette went out; I struck a match, it broke; I took out a new one, it broke. My wife took the box from me and calmly lit a fire. For some reason, the mouthpiece tasted bitter. I extinguished the cigarette and took the cup in my hands.

— "Like a cat on a piece of meat," — I continued with the thought that had stubbornly settled in my mind.

— "Nonsense, you've become paranoid. Comrade Stalin is satisfied with you; otherwise, you wouldn't be a member of the Central Committee of the party and the Central Executive Committee of the USSR. And Bukharin..."

— "Bukharin... What do you know about Nikolai? He is going through hard times now."

— "You have nothing to reproach yourself for!"

— "He smiled so slyly and almost whispered, — here Belotsky skillfully mimicked the NKVD officer, — 'Is it true that at one time you shared the opinion of some Trotskyists on the construction of the Red Army?'"

— "Which Trotskyists, what nonsense?!" — my wife did not understand.

— "You can't explain this to him; for him, the main thing is to wash away the stain — he won't have enough life for that." — I didn't have to explain this to my wife: she knew it already.

— "You need to go to Moscow, to Comrade Stalin."

— "Yeees."

Belotsky Moris Lvovich.

From September 24, 1933, to March 22, 1937 — first secretary of the Kyrgyz Regional Committee of the party. Born into a family of civil servants in the town of Lipovichi, Kyiv province. From 1916 to 1918, he was associated with anarchists; from August 1918, he was a member of the RCP(b).

Participant in the struggle for the establishment of Soviet power in Ukraine. From 1919 to 1922, he was engaged in political work in the Red Army. Awarded two Orders of the Red Banner: for distinction on the Polish and Wrangel fronts and for distinction in the liquidation of the Kronstadt rebellion as a delegate to the 10th Congress of the party.

From 1924 to 1931 — engaged in diplomatic and military-political work: consul in the Bukhara Soviet Republic, head of the department of the Skopin District Committee of the party, responsible worker of the North Caucasian Regional Committee of the party. From 1932 to 1933 — deputy chairman of the Central Council of the USSR Osoaviakhim.

His last position was first secretary of the Kyrgyz Regional Committee of the VKP(b).

In Kyrgyzstan, M. L. Belotsky made considerable efforts to eradicate factionalism within the republican party organization, to achieve its organizational and ideological cohesion, and to internationalize all local life. He was personally well acquainted with N. Bukharin, who visited Kyrgyzstan at least three times during this period, both for work and for rest at the Issyk-Kul resort of Koy-Sary. During his tenure as the first secretary of the Kirgiz Regional Committee, he was elected a delegate to the XVII Congress of the VKP(b), a member of the Central Committee of the party and the Central Executive Committee of the USSR. Under his direct supervision, the Constitution of the Kyrgyz SSR of 1937 was prepared. But under him, the active phase of the repression of party and Soviet figures in the republic also began.

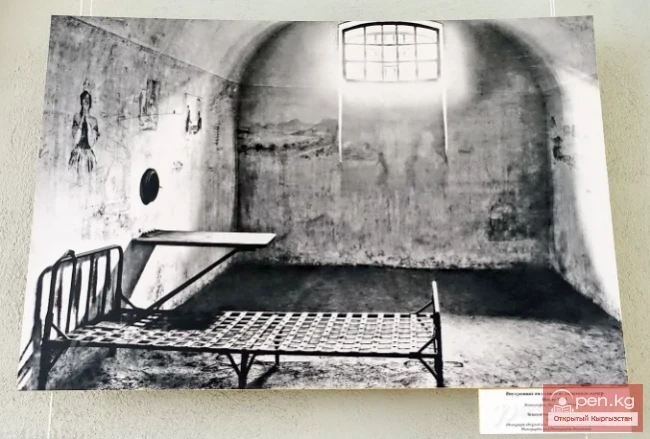

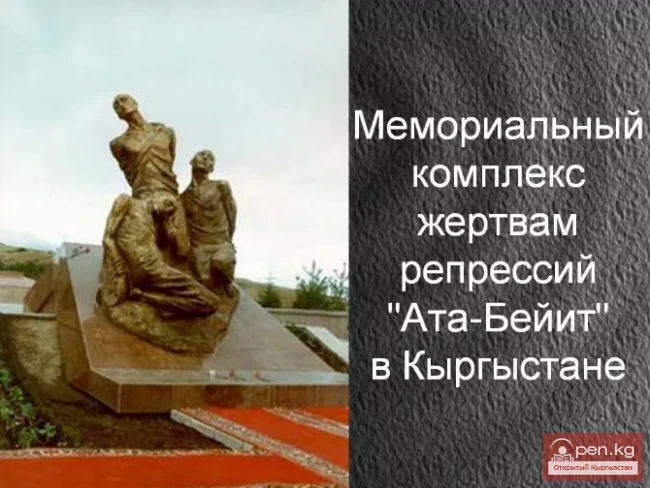

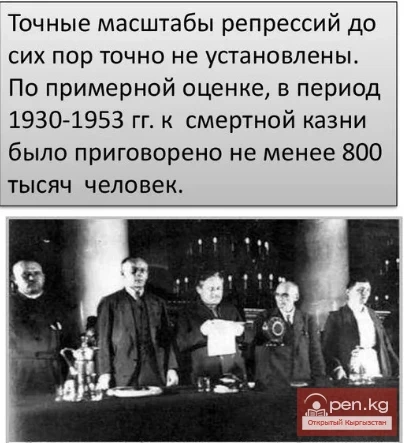

Belotsky himself also received so-called "compromising" materials with accusations of Trotskyism. The VIII Plenary of the Kirgiz Regional Committee on March 22, 1937, relieved him of his duties as the first secretary of the republican party organization, and he was recalled to the disposal of the Central Committee of the VKP(b). On July 9, 1937, M. L. Belotsky was expelled from the party by the decision of the CPC under the Central Committee of the VKP(b) (protocol No. 213) and repressed along with his entire family. When and how his life ended is unknown. According to some sources, M. L. Belotsky died in 1938, according to others — in 1944.

Sentence and Rehabilitation of E. D. Polivanov