Reflections on the Arrest of Tokchoro Joldoshev

Behind the dry lines of archival documents stands another tragically interrupted life. Let's imagine how it was.

Tokchoro Joldoshev — the People's Commissar for Education of the Kirghiz ASSR — sat at his desk and could not understand the meaning of the phrase he had just read. The white sheet with a red stamp at the bottom seemed to him like a huge piece of mountain ice, growing at the edge of an abyss, hiding beneath its transparent purity an unfathomable chasm. His hands seemed to have lost all strength. They reached for the paper but could not touch it. His eyes looked at the even typewritten lines and saw nothing but intermittent lines. Finally, one of them formed into a short and familiar word:

“DISMISSED.” Throughout his conscious life, Tokchoro had given orders and carried them out. And now, again and again, clinging to the word that had become the core of his life, he slowly grasped the meaning of what he had read. By the decision of the bureau of the Kirghiz Regional Committee of the VKP(b), Comrade Joldoshev was dismissed from the post of People's Commissar...

“Dismissed,” — what nonsense, what absurdity. Everything I did was aimed at implementing the party's decisions; I did nothing against them. — There was not a single thought in his head that could in any way explain what was happening.

Tokchoro opened a folder for documents. Inside were the papers he was supposed to sign today. His name still stood at the bottom. For a while, he stared at the even sheets of paper, then closed the folder. He pulled out the drawer of his desk and touched the handle of his revolver.

“Who will get it now?” — Joldoshev thought for some reason, — maybe Aliyev?

The messenger who brought the order cautiously shifted from foot to foot. Joldoshev raised his head, looked at the man with unseeing eyes, then lowered his gaze again. Next to the revolver lay a cherry-colored booklet of his party membership card.

“I am still a party member,” — a hot wave of joy returned his ability to think, — before doing anything, they will expel me from the VKP(b), and that means they will gather together. That’s when I will talk to them. They are my comrades in struggle; they always understood each other. I will say, and everyone will see that I am an honest Bolshevik, that someone is simply trying to slander me. Yes, I made mistakes; even a horse with four legs stumbles, but I am ready to correct it and work much better.”

He looked again at the messenger. He stood quietly, hardly breathing. His face was grim, and fear was frozen in his eyes.

“What is he afraid of — me, himself, or someone else? — Joldoshev looked once more at the revolver, took his party card from the desk, and put it in his breast pocket. — We will still fight. The party cannot fail to investigate my case; I am clean before it.”

He opened the lid of the inkwell that stood on the table, carefully dipped the pen, and resolutely, with a bold hand, signed the order of his dismissal.

“Let them see that I am loyal to the party's directives until the end and ready to carry out any of its orders.”

Joldoshev stood up and, stepping firmly, walked to the door of his office, holding in his right hand the freshly signed paper.

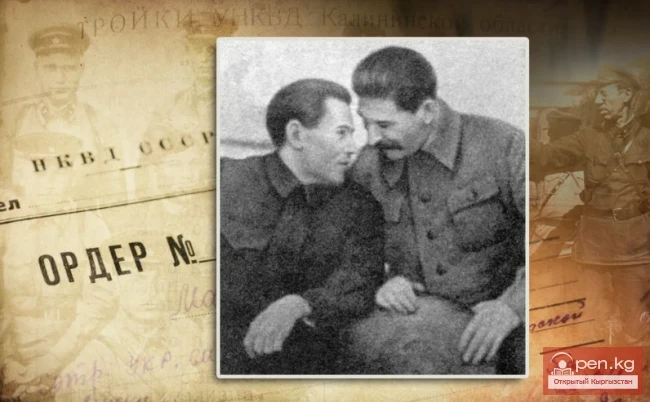

The messenger flinched and stepped aside. Tokchoro swung the door wide open and stepped into the reception area. He wanted to personally hand the order of his dismissal to the secretary. He took two steps into the narrow reception room and only then saw an NKVD officer standing in front of him. He held a gun pointed at Joldoshev.

— What are you doing? — The People's Commissar did not have time to finish. From the wall behind him, two more NKVD officers with weapons in hand stepped forward. The messenger stood behind him. Joldoshev thought he could hear the sound of that man's teeth chattering.

“So that’s what he was afraid of,” — the People's Commissar realized and felt weakness in his legs.

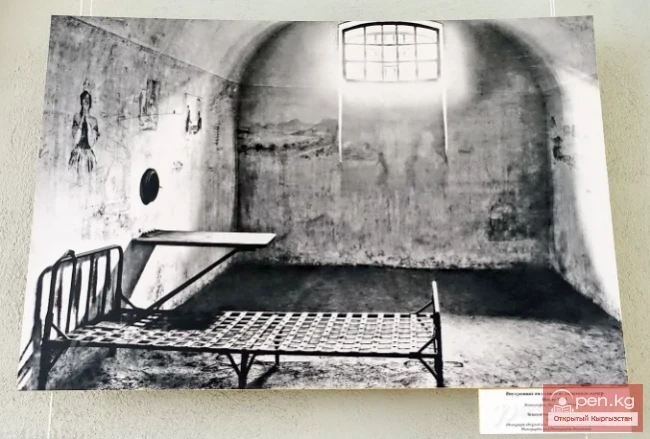

— You are under arrest, — the front officer said and pulled the trigger of the gun. Hands ran over his sides and chest, but Tokchoro did not understand who was searching him for weapons — the one standing on the left or the right. Joldoshev suddenly lost all ability to feel. He thought only of one thing — his membership in the party. He thought frantically, like about a lifebuoy, the last sip of water. How they led him out of the People's Commissariat, where they took him, what they said — he did not remember or understand anything. Only when the cell door closed behind him did Joldoshev realize that the world had split into two parts and freedom remained on the threshold. He took off his jacket, pulled out his party card, and stared at it for a long time.

A thought came to his mind that the people who arrested him might take this booklet away so that he would automatically be expelled from the party. “It would be easier to deal with me,” — Tokchoro thought and, clenching the card, began to pace the cell to find a hidden place to hide the booklet. The smooth walls had no cracks, and the wooden floor was neatly sealed. Joldoshev wandered around the cell for a long time, not noticing that the guard was watching him closely through the peephole.

— What is he doing in there? — asked the soldier of the approaching officer.

— He has been pacing the cell for the third hour as if he wants to hide something.

— No, — the officer laughed shortly, — he is like a filthy hen, running around with its egg — thinking how to deceive us. But, — he raised his finger admonishingly, — you can’t deceive the party. It senses enemies from three versts away...

Five days later, Joldoshev was expelled from the members of the Presidium of the Kirghiz Central Executive Committee, and only on November 17, 1935, a month and one day after his arrest, the Frunze City Committee of the party expelled Tokchoro Joldoshev from the party.

He was being led to the investigator. The heels of the guard's boots were clicking behind him, and Joldoshev suddenly felt scared at the thought that he had already gotten used to walking with his hands behind his back and did not consider it unnatural to walk under the escort of an armed soldier.

The escort walked with his hand resting on the open holster of his revolver. Even here, in the corridors of the internal NKVD prison, he was ready to shoot the arrested person for any reason. And all this had already become habitual, mundane, like the night interrogations.

— Stop, — the escort commanded, — against the wall.

Tokchoro turned to the gray plastered wall. Behind him, a door opened, and a sharp voice of the investigator came from behind it.

— Bring him here.

The guard roughly turned Joldoshev towards the door and gently pushed him in the back. Tokchoro stepped over the low threshold and stumbled over someone’s outstretched leg, falling heavily. The corner of a stool standing near the investigator's table cut deeply into his forehead. Blood flowed from the wound. Tokchoro slowly got up, wiped the blood from his face, and pressed the wound with a dirty handkerchief.

— So you stumbled in life as well, — an unfamiliar man sitting by the door, who had stuck out his leg to trip the arrested man, said, — when you decided to betray the people and joined the counter-revolutionary organization of Bulekbaev. You are our enemy, and we are dealing with you.

— I am not an enemy; I am a communist.

— Stubborn, bastard, — the investigator interjected.

— From today, you are not a communist, — the stranger said.

Joldoshev grabbed his pocket where his party card lay.

— Today, by the decision of the bureau of the Frunze City Committee of the VKP(b), — the stranger's voice carried an unmistakable triumph, — Tokchoro

Joldoshev is expelled from the party.

— And the meeting, you have no right to violate the charter.

— The charter is written for communists, not for fascists...

Tokchoro Joldoshev's last hope was extinguished.

Some pages from the biography of T. Joldoshev from 1927 to 1937

Read also:

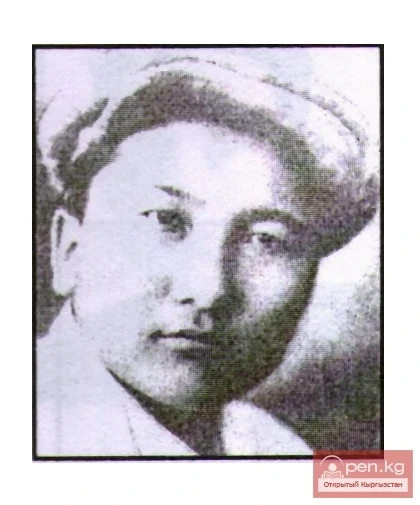

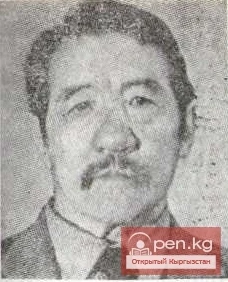

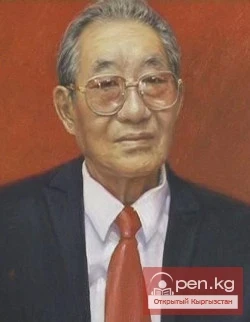

Dzholdoshev Tokchoro (1903-1937)

Dzholdoshev Tokchoro (1903-1937) - the founder of Kyrgyz literary criticism....

Types of Higher Plants Listed in the "Red Book" of Kyrgyzstan (1985)

Species of higher plants removed from the "Red Book" of Kyrgyzstan (1985) Species of...

Numerals, Mood, Verb in the Kyrgyz Language

Numeral Names. Cardinal numerals can be simple (1 - bir, 2 - eki, 3 - üç, 4 - dört, 5 - bet, 6 -...

The Career Ladder of T. Dzholdoshev

After graduating from the institute, Joldoshev was assigned to the Department of Public Education...

Types of Insects Listed in the 2004 IUCN RLTS Not Included in the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan

Insect species listed in the 2004 IUCN RLTS, not included in the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan 1....

Sentencing of Tokchoro Joldoshev

Dzholdoshev and a number of other comrades were vilified at the V Plenary of the Kirgiz Regional...

The Poet Baidilda Sarnogoev

Poet B. Sarnogoev was born on January 14, 1932, in the village of Budenovka, Talas District, Talas...

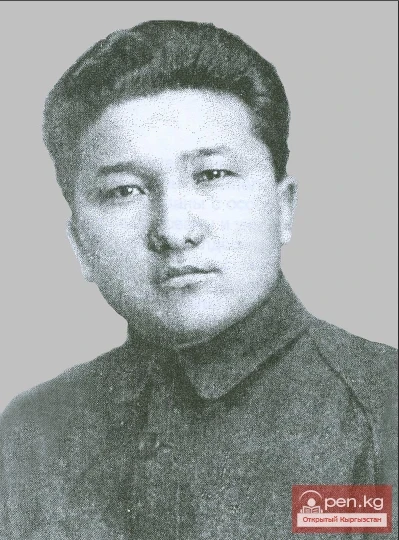

The future People's Commissar of Education of the Kirghiz ASSR, Tokchoro Joldoshev

“I AM A COMMUNIST!..”...

Prose Writer, Critic Dairbek Kazakbaev

Prose writer and critic D. Kazakbaev was born on June 20, 1940, in the village of Dzhan-Talap,...

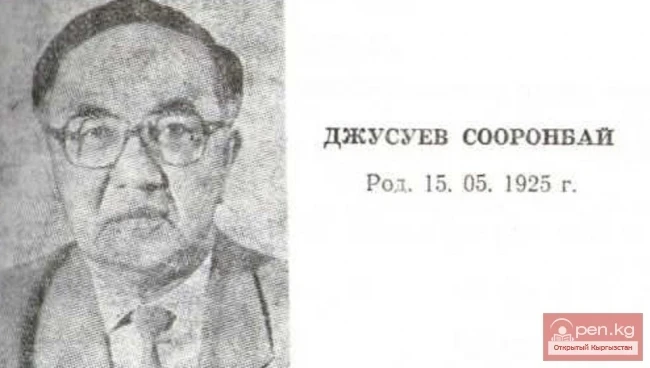

The Poet Sooronbay Jusuyev

Poet S. Dzhusuev was born in the wintering place Kyzyl-Dzhar in the current Soviet district of the...

Types of Insects Excluded from the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan

Insect species excluded from the Red Data Book of Kyrgyzstan Insect species excluded from the Red...

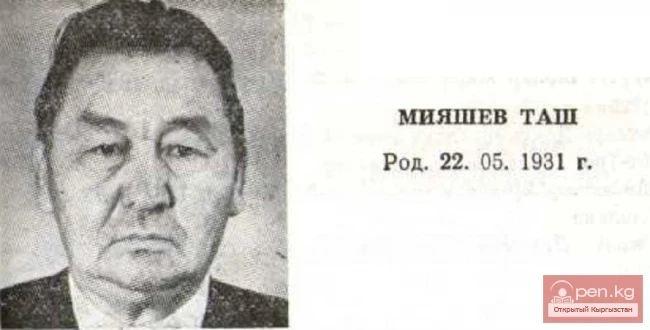

Poet, Prose Writer Tash Miyashev

Poet and prose writer T. Miyashev was born in the village of Papai in the Karasuu district of the...

Tourist Area Management Program

The project "USAID Business Development Initiative" (BGI), within the tourism...

Poet, Prose Writer Isabek Isakov

Poet and prose writer I. Isakov was born on September 1, 1933, in the village of Kochkorka,...

Poet, Prose Writer Medetbek Seitaliev

Poet and prose writer M. Seitaliev was born in the village of Uch-Emchek in the Talas district of...

Poet, playwright Dzhomart Bokonbaev

Poet and playwright J. Bokonbaev was born on May 16, 1910 — July 1, 1944, in the village of...

The Poet Alymkan Degenbaeva

Poet A. Degenbaeva was born on May 12, 1941, in the village of Belovodskoye, Moscow District,...

Omuraliyev Ashymkan

Omuraliyev Ashymkan (1928), Doctor of Historical Sciences (1975), Professor (1977) Kyrgyz. Born in...

Osmonov Anvar Osmonovich

Osmonov Anvar Osmonovich (1941), Doctor of Veterinary Sciences (2000) Kyrgyz. Born in the village...

Prose Writer Duyshen Sulaymanov

Prose writer D. Su laymanov was born in the village of Jilaymash in the Sokuluk district of the...

The Poet Kubanych Akaev

Poet K. Akaev was born on November 7, 1919—May 19, 1982, in the village of Kyzyl-Suu, Kemin...

Prose Writer Kasymaly Bayalinov

Prose writer K. Bayalynov was born on September 25, 1902—September 3, 1979, in the Kotmaldy area...

Poet, Playwright J. Sadykov

Poet and playwright J. Sadykov was born on October 23, 1932, in the village of Kichi-Kemin, Kemin...

Literary scholar, prose writer, poet Dzaki Tashtemirov

Literary scholar, prose writer, poet Dz. Tashtemirov was born on October 15, 1913—October 7, 1988,...

Poet, Prose Writer, Playwright Aaly Tokombaev (Balky)

Poet, prose writer, playwright A. Tokombaev was born in the village of Kainy in the present-day...

Critic, Literary Scholar, Poet Kachkynbai Artykbaev

Critic, literary scholar, poet K. Artykbaev was born in the village of Keper-Aryk in the Moscow...

Critic, Literary Scholar Abdyldazhan Akmataliev

Critic and literary scholar A. Akmataliev was born on January 15, 1956, in the city of Naryn,...

Atkurova Altynai Razbaevna

Attykurova Altynai Razbaevna Art historian. Born on November 23, 1973, in the village of Gulcha,...

Moods and Function Words in the Kyrgyz Language

Moods in the Kyrgyz Language The Kyrgyz language presents the following moods: imperative,...

Critic, Literary Scholar A. Sadykov

Critic and literary scholar A. Sadikov was born in the village of Kara-Suu in the At-Bashinsky...

Telekmotov Baktybek Asanbekovich

Telekmato Baktibek Asanbekovich Theater artist. Born in 1966 in the village of Ak-Tash, Kara-Suu...

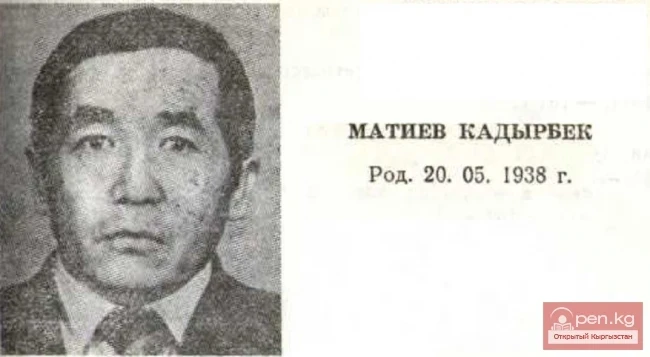

Critic, Literary Scholar Kadyrbek Matiyev

Critic, literary scholar Kadyrbek Matiev was born in the village of Ak-Took in the Suzak district...

Estebes Tursunaliev

Estebes Tursunaliev (born 1931) — akyn-improviser, People's Artist of the USSR (1988),...

The Poet Smar Shimeev

Poet S. Shimeev was born on November 15, 1921—September 3, 1976, in the village of Almaluu, Kemin...

Critic, Literary Scholar Bibi Kerimdzhanova

Critic, literary scholar B. Kerimdzhanova was born on October 30, 1920, in the village of...

Zhakypov Ybrai

Zhakypov Ybrai (1918), Doctor of Philological Sciences (1967), Professor (1969) Kyrgyz. Born in...

Sydykov Arstanaaly Arstambekovich

Sydykov Arstanaaly Arstambekovich Painter. Born on February 2, 1952, in the village of Kerben,...

Critic, Literary Scholar Keneshbek Asanaliev

Critic and literary scholar K. Asanaliev was born on June 10, 1928, in the village of Sokuluk (now...

Zakirov Saparbek

Zakir Saparbek (1931-2001), Candidate of Philological Sciences (1962), Professor (1993) Kyrgyz....

Critic, Poet, Prose Writer Kambarly Bobulov

Critic, poet, prose writer K. Bobulov was born on May 15, 1936, in the village of Osor, Nookat...

Asanbay Karimov (1898—1979)

Asanbay Karimov (1898— 1979) — an outstanding folk professional choorchu. A self-taught musician,...

Dzhumanazarova Asylkan Zulpuqarovna (1952)

Dzhumanazarova Asylkan Zulpukarovna (1952), Candidate of Chemical Sciences (1982), Professor...

Poet Mukambetkalyy Tursunaliev (M. Buranaev)

Poet M. Tursunaliev was born on January 11, 1926, in the village of Alchaluu, Chui region of the...

Poet Musa Djangaziev

Poet M. Djangaziev was born in the village of Karasakal in the Sokuluk district of the Kyrgyz SSR...

Weather Prophet Atay from Jumgal

Among the folk weather predictors, Atai from Jumgal was known for his observations of cloud...

Poet, Linguist Kasym Tynystanov

Poet and linguist K. Tynystanov was born on September 9, 1901—November 6, 1938, in the village of...