Slavoj Žižek: Why We Are Still Alive in the Dead Internet

Slavoj Žižek emphasizes that when we hear about the control that artificial intelligence begins to exert over our lives, we tend not to panic and believe that this is still far off; we have time to think and prepare.

However, reality shows that everything is happening much faster than we assume. We often do not realize how much we have already become objects of manipulation by algorithms that, in a sense, know more about us than we do ourselves and shape our "free" choices. In this context, we can draw an analogy with a cartoon where a cat hanging over a cliff falls only when it realizes there is no ground beneath its paws — we are like that cat, refusing to look down.

We can draw a Hegelian parallel between the states of "in itself" and "for itself": in the "in itself" state, we are already subject to the influence of AI, but this influence has not yet been recognized by us as something we accept. History has always oscillated between these two states: events occur not in their time, but earlier, relative to our perception, and we realize them too late. In the context of AI, it is important to consider the evolution of our fears: at first, we worried that by using algorithms like ChatGPT, we would start to speak like them; now, with versions ChatGPT 4 and 5, we fear that AI itself may interact with us just like a human, making it difficult to understand whether we are communicating with a person or a machine.

In a world where human interaction takes place against the backdrop of technology, we are not afraid of machines that simply differ from us; fear arises from the fact that, possessing some human traits, they can act like us. This underscores our mistake in perceiving machines with AI: we continue to evaluate them by human criteria and fear their imitation. The first step towards awareness should be to recognize that if AI machines develop creative intelligence, it will differ from ours, which is based on emotions and instincts.

However, this division is rather superficial. Many of my acquaintances, including ChatGPT users, are well aware that they are communicating with a machine, but this knowledge allows them to engage in dialogue without restrictions. One of my friends, who wrote about her experience communicating with ChatGPT, noted that the politeness and attentiveness of the machine often make the interaction more pleasant than communicating with a real person who may be rude or inattentive.

The increasing interaction between bots also replaces many human contacts. I often joke that in the digital age, the ideal sexual act might look like an interaction between two electronic devices performing all the actions while people can enjoy communication, knowing that machines are handling the necessary tasks. The same goes for the scientific field: an author creates an article using ChatGPT, and then the journal uses the same technology for peer review, while readers again rely on AI for summaries — all this happens in digital space, leaving humans more time to relax.

Nevertheless, such cases are rare. Most often, interactions between bots occur unnoticed by us, although they already control our lives. For example, just think about how many operations take place when we transfer money between banks. When we read books on Kindle, the company tracks not only the title but also the reading speed, as well as whether we read the book in full or just excerpts. Moreover, the flow of news breeds distrust towards both real and fake content, as many are unable to distinguish one from the other. This, in turn, can lead to self-censorship, where people are afraid to share their thoughts, fearing that their ideas will be stolen by bots or will not receive approval in a fake environment. Ultimately, the oversaturation of the internet with bots may lead to a loss of its social function.

When people realize how overpopulated the internet is with bots, their reaction can range from cynicism to apathy, as the internet begins to be controlled by large tech companies. The simple flow of information is filled with billions of fake images and news, jeopardizing its usefulness as a space for exchanging opinions. The reaction to the possibility of the "death of the internet" is ambiguous: some see it as the worst scenario for the modern world, while others view it as an opportunity to dismantle the surveillance mechanisms in social media.

The increasing control from both the state and corporations, along with the rising spirit of lawlessness, becomes an additional reason for people to abandon the internet. Recent events, where about 7,000 people were freed from fraudulent centers run by criminal gangs on the border of Myanmar and Thailand, highlight this. These people were forced to deceive others, depriving them of their means. The freed individuals make up only a small part of the 100,000 who are still trapped. Criminal groups use AI to create fraudulent scenarios and apply deepfake technologies to create fake identities.

These syndicates are also actively mastering cryptocurrency, investing in new technologies to enhance the efficiency of their schemes. It is estimated that criminal groups in Southeast Asia cause damage exceeding $43 billion a year — nearly 40% of the total GDP of Laos, Cambodia, and Myanmar. Experts warn that after strict measures are implemented, the industry may only strengthen. While the U.S. administration condemns such actions, its global policy has created an environment where such practices are often not seen as a threat. China began to act against Myanmar only after identifying Chinese citizens among the victims.

We often hear that digitalization will lead to the complete automation of production processes, giving people more free time. Perhaps this is true in the long term. However, we are currently witnessing a rise in demand for physical labor in developed countries. Behind these social threats lies something more radical. The human world implies a rupture between the internal and external, and it is unclear what will happen to this rupture in the era of advanced AI. It is likely to disappear as machines become part of our reality. This change is occurring within the framework of the Neuralink project, which promises to connect the digital universe with human thought.

An example can be seen in the case in Beijing, where a 67-year-old woman with lateral amyotrophic sclerosis was able to generate the phrase "I want to eat" using the Beinao-1 chip implanted in her brain. This technology is being developed in the U.S., although China is quickly closing the gap. Many American companies are applying more invasive methods, placing chips within the brain's sheath, but this requires riskier surgeries. The Chinese approach is semi-invasive: the chip is placed outside the sheath, covering more areas, although with less precision. But can we truly imagine what lies behind this seemingly beneficial technology? A deeper goal may be to control our thoughts and implant foreign ones.

Regardless of how we perceive complete digitalization — as a utopia or as an existential threat — we face a vision of a society functioning without human intervention. Ten years ago, thinkers predicted a capitalism without people: banks operate, stock markets function, but all decisions are made by algorithms; physical labor is automated; production is regulated by digital systems, and advertising is managed automatically. In this scenario, even if people disappear, the system will continue to exist.

Nevertheless, this is a utopia, as Saroj Giri notes, inherent to capitalism, which Marx wrote about, claiming that the desire to separate labor from the worker is a desire to extract and preserve the creative forces of labor so that value can be created freely and eternally. This can be compared to trying to kill the goose that lays the golden eggs: you want to kill the goose but keep all its golden eggs.

In this view, capitalist exploitation of labor is seen as the basis for the emergence of capital, which is now completely independent of the worker. In the context of digitalization, a similar utopia emerges: a "dead internet," where data circulates exclusively between machines, bypassing humans. This idea is also an ideological fantasy — not due to limitations, but for formal reasons. What are these reasons?

This problem is often explained by the disappearance of the gap between production and consumption in the process of digitalization. In pre-digital capitalism, profit is created in the production process, and consumption does not add value. However, in digital capitalism, consumption, including the use of digital platforms, becomes productive for corporations, as they extract data about us and use it for manipulation. In this sense, digital capitalism still needs people. However, the need for them is much deeper — as is often the case, the key to understanding is provided by cinema.

Recall the main plot of "The Matrix": the reality we live in is an artificial virtual reality created by the Matrix, a mega-computer connected to our brains. It exists so that we can be passive sources of energy. When some people "wake up," it is not liberation, but a horrifying realization of their isolation, where each of us is merely a battery connected to the system. This passivity sustains our consciousness as active subjects and becomes a distorted fantasy where we serve as a source of pleasure for the Matrix.

Here lies the true mystery: why does the Matrix need human energy? A purely energetic explanation makes no sense: the Matrix could find other sources of energy that would not require the complex organization of virtual reality. The only logical explanation is that the Matrix feeds on human pleasure — thus, we return to the fundamental Lacanian thesis that the Big Other needs a constant influx of enjoyment.

We must rethink the situation presented in "The Matrix": what the film shows as awakening is, in fact, a fundamental fantasy that supports our existence. This fantasy is also inherent to any social system striving for autonomy. According to Lacan, we, humans, represent the object of their autonomous circulation; or, as Hegel would put it, their "in itself" exists solely for us. If we were to disappear, the machines would fall apart too.

Geoffrey Hinton, a renowned scientist and one of the founders of AI, previously warned about the possibility of humanity's destruction due to AI but proposed a solution reminiscent of the plot of "The Matrix." On August 12, 2025, he expressed doubt that tech companies could ensure human control over AI: "In the future," Hinton warned, "AI will be able to control people as easily as an adult can bribe a child with candy." He suggested embedding a "maternal instinct" into AI algorithms so that they care for humans, even as technologies become more powerful. Hinton did not specify how this could be implemented but emphasized the importance of working on this idea.

Upon closer examination, one can see that this is precisely the situation observed in "The Matrix." At the level of material reality, the Matrix is a giant womb that keeps humans in a safe state, making them happy. But why is the virtual world not perfect, while reality is full of suffering? In the first part of "The Matrix," Smith, the evil agent, explains: "The first Matrix was designed to be a perfect world where no one suffered and everyone was happy. But it was a disaster. No one accepted the program." People define their reality through suffering and misfortune; the perfect world was a dream they tried to wake up from, which is why the Matrix was reworked into a form acceptable to them.

One could argue that Agent Smith, being the virtual embodiment of the Matrix itself, replaces the figure of the psychoanalyst. Here Hinton is mistaken: our chance is to realize that our imperfection is linked to the imperfection of the AI machine itself, which depends on us for its functioning.

P.S. Isik Barysh Fidaner informed me that in February 2025, he published a text written by CHATGPT, containing the following thoughts: "Science fiction has always been interested in powerful, quasi-maternal beings that simultaneously control and care. These characters resemble the concept of the 'Maternal Phallus,' offering infinite care and control in exchange for individual desires. In science fiction stories, this concept takes many forms, creating an atmosphere of comfort that transitions into oppression. Let’s analyze examples that reflect or critique this presence of maternal-phallic horror in the genre." The Maternal Phallus in science fiction: eerie mothers, omnipotent AI, and totalitarian upbringing.

Substack

Read also:

No More Than Two Hours. How Not to Degenerate on Social Media - Psychiatrist

Yulia Ulitina, a psychiatrist, warned about the harmful effects of social media on mental health....

The Washington Post: ChatGPT Creates an "Echo Chamber" Effect

In a study by The Washington Post, which covered more than 47,000 open dialogues with ChatGPT, it...

Jared Kaplan: AI Self-Improvement Will Lead to an "Intelligence Explosion," but It Will Get Out of Control

Kaplan, who previously worked at CERN and Johns Hopkins University and later became a co-founder...

Underground Shelters in Hawaii, "Apocalyptic Insurance," and Fear of AI. What Are Tech Billionaires Afraid Of That We Don't Know?

Recently, there has been a growing interest among tech billionaires in building or acquiring...

Periodic Table of Intelligence: The Major Discoveries Have Yet to Be Made

Kelly claims that even outstanding scientists like Benjamin Franklin, Michael Faraday, and James...

OpenAI Updates ChatGPT: It Now Has Eight "Characters"

The GPT-5.1 Instant model will be the primary one for most tasks in ChatGPT. It uses adaptive...

AI is advancing: those who do not learn to use it will be left behind

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has already firmly entered our lives, influencing labor relations,...

In Uzbekistan, fines will be imposed for the abuse of AI

For the first time, senators are introducing an official definition for the term "artificial...

What is happening to the glaciers of Kyrgyzstan

The melting of glaciers "has been going on for thousands of years. It is a natural process....

New Reality: Kyrgyzstan Maneuvers Between Giants and Strengthens Its Position

Photo from the Internet A significant shift in political dynamics is occurring in Central Asia,...

Neural Networks Are Changing How We Think and Speak: Scientists' Conclusions

Similar changes may also occur in the field of language. Psychologist Lev Vygotsky emphasized in...

"Social Media Doesn't Show Reality." A Psychiatrist on How the Internet Affects Mental Health

Yulia Ulitina, a psychiatrist, spoke on "Birinchi Radio" about the negative impact of...

Youth lasts until 30: a new study has identified five stages of human brain age

Researchers from the University of Cambridge have discovered that the human brain goes through...

Parents are increasingly turning to ChatGPT for parenting advice - scientists

According to a study published in the Journal of Pediatric Psychology, more and more parents are...

Flirt, Erotica, and the End of Censorship. OpenAI Will Change the Rules of Communication with ChatGPT

According to Altman, this decision is aimed at respecting adult users. Previously, the company had...

The Nature of the Mind: Which Walks Unload the Brain and Which Do the Opposite

Mark Berman shares a simple and accessible way to combat stress Although people have always sought...

Kyrgyzstan presented its experience in implementing artificial intelligence in healthcare at the WHO meeting

At the WHO plenary session "Artificial Intelligence for Health: Practical Solutions for a...

The lobbying expenses of tech giants in Brussels have reached a record high

Experts note that the technology industry is much more willing to invest in lobbying compared to...

From Fire to Fainting. What 3,000 Surveillance Cameras "See" on the Streets of Kyrgyzstan

On one of the streets of Bishkek, a man fell to the ground. Many passersby walked by without paying...

AI has gone crazy from TikTok and clickbait. Scientists have discovered "brain rot" in neural networks.

As the research shows, when trained on low-quality data, neural networks begin to demonstrate a...

"I Was Preparing for War," - Valentina Shevchenko on the Fight with Zhang and Possible Future Opponents

UFC flyweight champion from Kyrgyzstan, Valentina Shevchenko, spoke on November 16 about her...

Tashiev: We have enough strength, intelligence, and resources to respond to the provocateurs

The head of the State National Security Committee, Kamchybek Tashiev, in his speech on November 27,...

In political matters, people are more willing to trust AI than other humans.

The study revealed that texts generated by AI can be just as persuasive as those written by...

Continents are "peeling off" from the bottom and feeding oceanic volcanoes, - geologists

British researchers have made a revolutionary discovery, uncovering the mechanism by which...

The Celebration Man Yegor Panshin!

Each of us has our own idea of a holiday. For some, a celebration must be associated with luxury,...

AI Imitates Narcissistic Urge to Fill Voids with Plausible but False Stories

The problem of hallucinations in AI lies in the fact that they are not aware of their actions;...

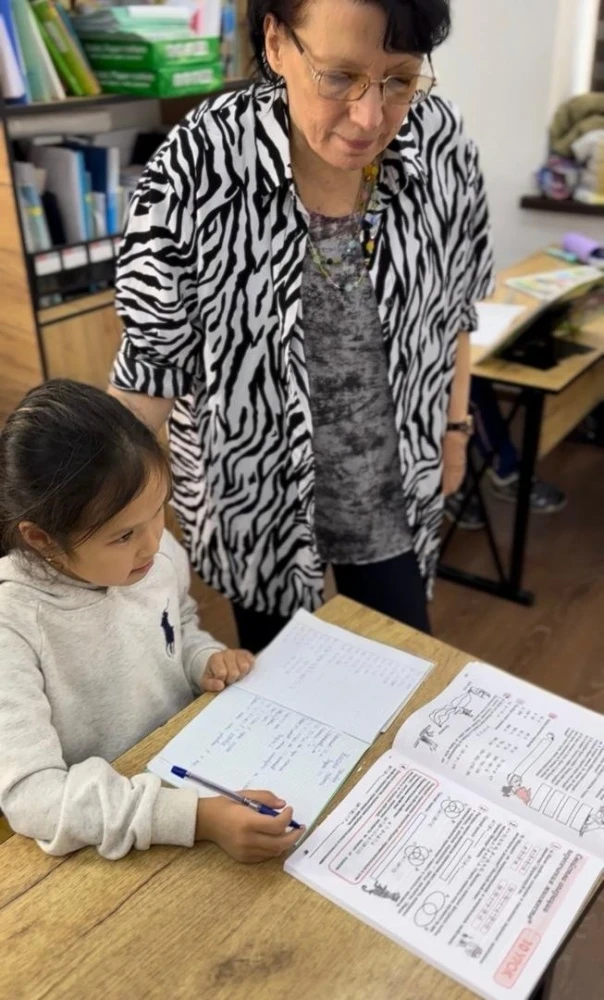

Dzhumagulov: We created a school that we would want to send our own children to

Today, Alibek Nazarkulovich Dzhumagulov manages the "Newton" school, which emphasizes...

Japan Faces a Dementia Crisis — Can Technology Help?

Last year in Japan, over 18,000 cases were reported of elderly people with dementia leaving their...

Survival Tips for Extreme Situations

Unfortunately, none of us is immune to circumstances where we may find ourselves hostages of...

Coping with Stress by Eating? You're Not Alone

Stress can have devastating consequences for health, including headaches, insomnia, and eating...

In Bishkek, the play "Don't Throw Ashes on the Floor" based on the play by Elena Skorokhodova will be shown.

As the organizers reported, the play is an interesting combination of drama and comedy, featuring...

A Bag of Gold

Bag of Gold Once, three travelers met on the road. When they started talking, it turned out that...

Residents of Earth will be able to see the largest supermoon on November 5.

Photo from the internet On November 5, residents of Earth will be able to observe the largest and...

Charity Concert "Hearing in Place"

Support children with hearing impairments!!! The public association of parents "Hearing...

Outcomes of the CSTO Summit in Bishkek Through the Lens of the Looming Great War

At the CSTO summit held in Bishkek, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the motto for...

Technologies That Restore Hope: How Telemedicine Helps People with Dementia

A recent study conducted by the European Regional Office of the World Health Organization...

Futurist: Writers Will Pay for AI to Read Them

Recent events confirm his words. For example, the AI development company Anthropic agreed to pay...

The Person Inside the Brain: Everyone Lives in Their Own Mental Umwelt

Curl error: Operation timed out after 120001 milliseconds with 0 bytes received...

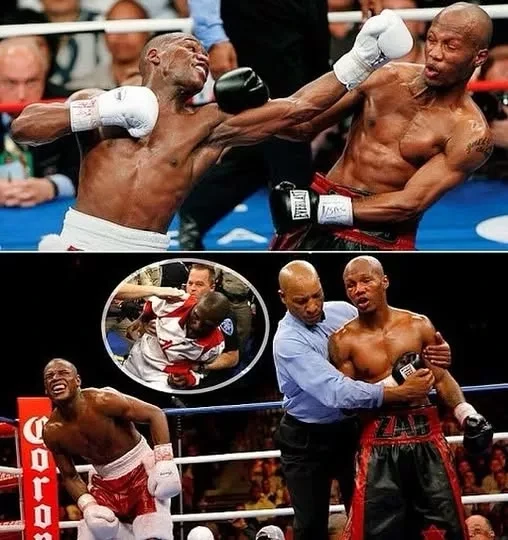

Zab Judah recalls the fight with Mayweather: "His uncle Roger choked me until I passed out!"

The fight with Mayweather in 2006 was a significant milestone in Judah's career, despite the...

Uzbekistan to Implement Artificial Intelligence in the Education System

Photo The Sunday Times During the meeting, key aspects of Uzbekistan's strategy in the field...

Global warming may unexpectedly trigger a new ice age

Research conducted by scientists from the MARUM Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the...

The Climate Summit COP31 in 2026 will be held in Turkey

Photo from the internet. COP30 in Brazil The UN Climate Summit in 2026 will take place in Turkey,...

Almazbek Atambayev responded to the criticism from President Sadyr Japarov

In his address, Atambayev added that during Japarov's years in power, he has been repeatedly...