“If we cease to exist, Semirechye will continue to live…”

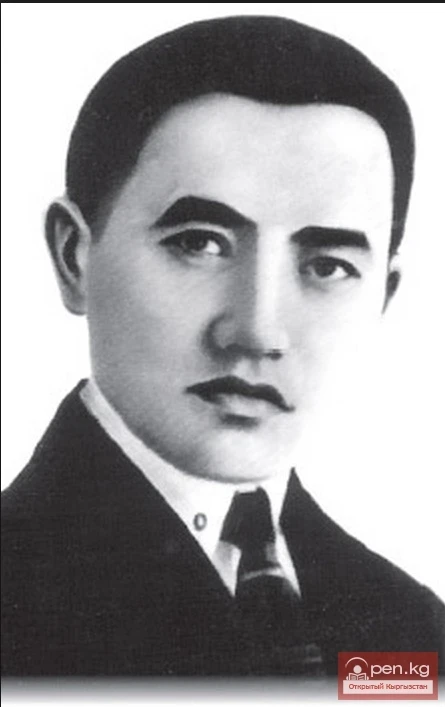

Chekmenyev Nikolai Simonovich is a writer, one of those who stood at the origins of Russian literature in Kyrgyzstan.

“A great writer rarely enjoys the noisy glory of universal recognition during their lifetime. Away from literary skirmishes, on untrodden paths of understanding life and humanity, their talent quietly but firmly takes root, while other literary brethren, heroes of sensational brawls, either do not notice them at all or ironically laugh at how diligently and painstakingly the writer works on each of their lines. Years will pass before it becomes obvious to everyone that he was head and shoulders above many of his contemporaries.

This is how, generally speaking, the literary fate of writer Nikolai Simonovich Chekmenyev appears today.”

Nikolai Chekmenyev was born in 1905, into a peasant family of modest means, in the village of Raevka in the Orenburg province. Here, the future writer completed a three-grade rural school. His childhood was spent in his native village, where he, along with his peers, would go out at night and gaze at the starry expanse by the fire, and together with everyone, endured the hardships of peasant life.

The fate of the villagers became particularly harsh when, after an unprecedented drought, hunger “came” to the village. People fled to other lands, hoping to find not only bread but also a new life. This was the case with the Chekmenyev family when, in 1920, escaping from hunger, they moved to Kyrgyzstan, which since then became the second homeland of future writer Nikolai Simonovich Chekmenyev.

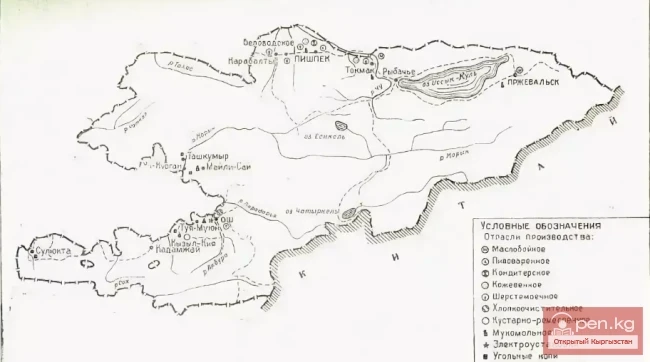

In the 1920s, peasants everywhere united into labor artels for joint land cultivation. Such an agricultural artel was organized in the vicinity of the city of Pishpek. The Chekmenyevs joined this artel.

But two years later, after the land-water reform of 1922, the artel disbanded.

All these harsh life circumstances, which directly affected Nikolai, contributed to his early maturation, which, by the way, was very characteristic of that harsh time when young men took on responsibility for many things. And Nikolai Chekmenyev began his independent life at the age of fifteen.

In 1922, their family moved to the city of Pishpek – a small provincial town, but even here, revolutionary life was “boiling.” In the only city cinema, not only films were shown; many vital issues were resolved here. Many forms of art were emerging, including poster art, sometimes calling for great deeds, sometimes criticizing slackers, and often even “taking aim” at world imperialism itself. Many posters were needed for red huts, red yurts, red convoys, for “living” newspapers, and they were also necessary for advertising films. A lot of posters required many artists. A poster artist is a special “breed” of artist, able to find fresh news and “know everything about everything.”

One such artist was seventeen-year-old Nikolai Chekmenyev, who was then working in the cinema of the city of Pishpek. Two years later, the inquisitive young man, eager to be in the thick of events, began collaborating with the local newspaper “Krestyanskij Put,” which started publishing after the formation of the Kyrgyz Autonomous Region. History knows that in 1924, the newspaper “Erkin Too” was also published in Pishpek, marking the beginning of printing in the republic.

“Peasant Life” became the laboratory where Nikolai Chekmenyev conducted his first “experiments” in the form of poems and stories, which indicated to the young man the necessity of “mastering literary work” – there was still much to learn. Knowledge of life and the desire to write is not everything. And in 1926, Nikolai Chekmenyev left his job at the newspaper and went to Moscow – to study at the Workers' Faculty of Arts.

“Institutes of the Red Professorship,” “rabfaks,” and other educational institutions were opening in all major cities of the young Soviet republic. Such educational institutions opened in Moscow and Leningrad were particularly popular. It was there that all the “upstarts” from Central Asia, including Kyrgyzstan, were trained. Most of them lacked the necessary school education. But the country needed specialists for all vital sectors, and they needed to be trained urgently. It should be noted that they returned home well “armed” both professionally and politically.

Nikolai Simonovich graduated from the Workers' Faculty of Arts in 1930 and was immediately enrolled in the literary department of the Moscow Editorial and Publishing Institute. In Moscow, the future writer studied, became a member of the Society of Peasant Writers led by P.I. Zamoysky, and wrote novellas. He took an active part in the literary life of the capital.

Even in 1927, he wrote the novella “Pastukh Sadyk” – the first major work of the young writer. In it, he demonstrated a fairly deep knowledge of the national way of life of the Kyrgyz on the eve of the October Revolution, managing to reflect the inevitable process of the destruction of the old order, its “relics” that humiliated and offended the impoverished and defenseless poor.

“Pastukh Sadyk,” as specialists believe, is one of the best early works of N.S. Chekmenyev. It was translated into Kyrgyz by S. Karachev and published as a separate book by the Kyrgyz Republican Publishing House in 1929.

Two years later, in 1931, in Leningrad, the State Publishing House of Artistic Literature “gave a ticket” to the life of the young writer's new novella – “Sekty.”

In 1933, Nikolai Simonovich, having graduated from the Moscow Editorial and Publishing Institute, returned to Kyrgyzstan for permanent work.

N.S. Chekmenyev was one of the first elected to the Union of Writers of the USSR.

From 1933 until the end of his life, N.S. Chekmenyev's creativity was connected with Kyrgyzstan. Here he worked as a literary employee for the newspaper “Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan” and the publishing house “Kyzyl Kyrgyzstan,” as a research associate at the museum, and as a literature teacher in a secondary school.

N. Chekmenyev also engaged in translations into Russian of works by Kyrgyz writers. Thus, in 1934-1936, he translated into Russian the collection of poems “Plody Oktyabrya” and the poem “Zolotaya devushka” by Dzh. Bokonbaev.

The military-historical theme had long attracted the writer. In the 1930s, N.S. Chekmenyev began working on materials about the history of the Civil War in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. In 1934, the first fragment of the planned novel on this topic – “Tak reshil voenkom” was published. Before the Great Patriotic War (in 1940), N.S. Chekmenyev wrote and published the novella “Kometa.”

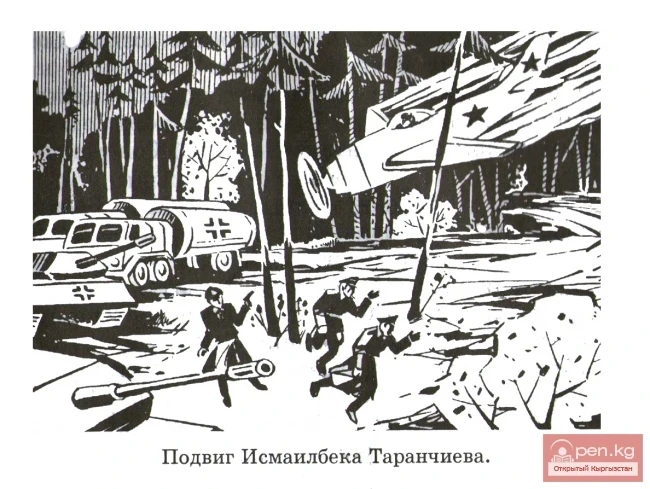

The war began, and Nikolai Simonovich went to the front as a unit commander with a weapon in hand to defend the Motherland. But even here, at the front, his literary gift was needed. And, “equating the pen to the bayonet,” N.S. Chekmenyev became a front-line literary worker. And then… after the war, the writer would have much to tell readers in his works.

In the post-war years, new works by N.S. Chekmenyev were born. “Zeleny klin” (1950) tells about the livestock breeders of the Tien Shan. The collection of novellas and stories “Kometa” was released in 1956. It included, in addition to the novella “Pastukh Sadyk,” published in Moscow in 1929, eight more novellas and stories. And all of them are about the life of ordinary people in Kyrgyzstan during the pre-war, wartime, and post-war periods and about the main dream of these people – to build a new, better life.

In 1960, during the anniversary of the Victory over fascist Germany, the Kyrgyz Educational and Pedagogical Publishing House released a collection of stories by Nikolai Simonovich – “V'yuga.” And here, the narrative is about the past, the combat, the unforgettable.

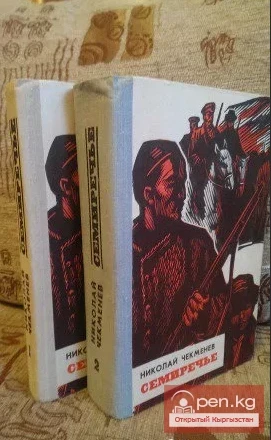

All the post-war years, Nikolai Simonovich did not part with the long-conceived theme – the history of the Civil War. In 1952, the novel he wrote – “Pishpek 1918 goda” was published. And… two years later, in 1954, the first book of the novel “Semirechye,” and in 1958 – the second part of this novel about the events of the October Revolution and the Civil War in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, which unfolded over a vast territory – Semirechye. Against the backdrop of tragic historical events, the writer vividly depicts the life, customs, and culture of the peoples inhabiting this land, which once became part of the Russian Empire.

In 1960, the publishing house “Kyrgyzstan” released this large epic work with a circulation of 150,000 copies. “If we cease to exist, Semirechye will continue to live,” wrote reader I. Karpov to Nikolai Simonovich in a letter.

The novel “Semirechye” was published in 1954-1958, precisely during those years when we, students of the historical faculty of the Kyrgyz State University, were learning the “basics” of the history of the republic. The novel “Semirechye,” along with other historical novels, was a textbook for students. In my memory, at least, it remains as the best textbook on the history of the October Revolution and the Civil War. And considering that it was a time of great scarcity of textbooks, when the release of works, especially historical ones, was under the vigilant eye of the relevant authorities, it is clear that the novel “Semirechye” could well satisfy our student “hunger.” Reading it, we felt as if we were listening to the account of an eyewitness who experienced all the events. And we successfully passed exams thanks to the knowledge gleaned from this novel.

And today, rereading the novel “Semirechye,” one realizes that it is indeed a work of epic scale, better than which, at least in the 1960s, was not written by any author in the Russian literature of Kyrgyzstan.

In the preface to the 1977 edition titled “If we cease to exist, Semirechye will continue to live. A word about Nikolai Chekmenyev,” Valery Vakulenko writes: “This book was born with difficulty. Its fate was even more difficult. What was obvious to most readers and raised no doubts was not understood and questioned by those who saw in a work of art not a generalized and typified aesthetic and philosophical exploration of real life, but a photographically dispassionate chronicle of events.”

In fact, “extraordinary will and love for the chosen, truly creative conscientiousness and high professional integrity” of a true master have always evoked, if not a cry of outrage, then annoyance and grumbling regarding the created work. Especially those who consider themselves particularly “professionally equipped” but… are unable to “create” at least a semblance of what they are trying to “understand and accept” make the greatest effort to “not understand and not accept” the new creation.

Events related to the publication of the historical work of the great poet A.S. Pushkin – “History of Pugachev” come to mind. Contemporaries criticized him for allegedly not “opening anything new, unknown.” A.S. Pushkin countered: “But this entire era was poorly known. Its military part had not been processed by anyone… I confess, I thought I was entitled to expect a favorable reception from the public, of course, not for the very ‘History of the Pugachev Rebellion,’ but for the historical treasures attached to it.”

After the publication of the novel “Semirechye,” some critics puzzledly asked: “Is this a novel or a chronicle?”

The history of literature, as we see, knows many examples of how, striving for historical truth, the author preserves not only the real names of the heroes but also the situations, in which the main characters and witnesses are the characters themselves. Naturally, here not only individual facts, carefully preserved by the author of the book, are called into question, but entire plot collisions. Otherwise, even the very idea of the book may suffer.

N.S. Chekmenyev is meticulously precise in investigating real events and does not allow himself the slightest deviation from historical reality. Some contemporaries recognized themselves in the heroes of the novel “Semirechye.” Although some of their traits were intentionally exaggerated, others – according to the design of the novel, on the contrary, were blurred.

It is clear that they were outraged and accused the writer of consciously distorting the true facts and events.

Meanwhile, however contemporaries of the author evaluate N.S. Chekmenyev's novel “Semirechye,” one thing is clear: in the Russian literature of Kyrgyzstan, it is an extraordinary phenomenon.

“Not competing” with the best works of the multinational literature about the Civil War, it convincingly and uniquely “complements and continues their theme, recreating yet another link in the revolutionary-epic picture of life throughout the Soviet country in those harsh and beautiful years of the struggle for the future,” believes V. Vakulenko, analyzing the responses of benevolent readers to the novel “Semirechye” (5).

Slowly, carefully, preserving historical realities, the writer recreates pictures of the past occurring on this land. From the pages of this “ocean-like” epic, people speak to us, names of whom today are given to the streets of the capital – Yakov Logvinenko, Alexey Ivanitsyn, Sayakbay Karalaev. Moreover, they are presented here exactly as they were in real life – people who seem “ordinary” and “simple” yet at the same time special – historical. Personalities who fervently believe in the triumph of the cause they serve selflessly and sincerely are often too energetic, emotionally fervent, and yet, soulfully sensitive and perceptive.

Nikolai Simonovich Chekmenyev was just as soulfully sensitive, perceptive, and strong in life. Unfortunately, far from every, especially seasoned writer demonstrates their goodwill, and even more rarely enthusiastic feelings regarding the creativity of their contemporary colleagues or idols. Nikolai Simonovich always tried to do this. In the republican periodical press since 1939, one can find his essays on the creativity of Kubanychbek Malikov and Kasymaly Bayalinov, many folk akyns who dedicated not only their creativity but their entire lives to the people. Here are stories about Kyrgyz literature, builders of Orto-Tokoy, and workers of the village. About his “unforgettable meetings” with Hungarian writer Mate Zalka, N.S. Chekmenyev writes in the Kazakh periodical press.

Perhaps Nikolai Simonovich was very close in spirit to the creativity of N.V. Gogol. He particularly highlighted it and dedicated several publications in republican newspapers to it. Moreover, in the works of Kyrgyz writers, N.S. Chekmenyev found much that resonated, in his opinion, with the thoughts and ideas of N.V. Gogol expressed in his work.

It should also be noted the enormous delicacy of N.S. Chekmenyev as a publicist. Whenever he wrote about national literature or its national masters, he consulted or even co-authored with “carriers” of this culture. In collaboration with poet T. Umetaliev, he wrote the article “Akyn-patriot” in the newspaper “Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan” in December 1950, and in the newspaper “Leninchil zhash,” in collaboration with K. Eshmambetov, the article “Gogol and Kyrgyz Literature” was published in December 1952. Perhaps in the works of N.V. Gogol, Nikolai Simonovich saw what many, even those who loved him, could not feel.

The publications of N.S. Chekmenyev that we managed to read in the periodical press, especially in newspapers, that is, the most accessible means of information at that time, are always benevolent. This cannot be said about many contemporaries – colleagues in pen, who “responded” in the same mass media to the works of N.S. Chekmenyev. Some of them almost as if ideological installations directly called: “Create high-ideological artistic works.” Does this mean that the creations of N.S. Chekmenyev are not high-ideological?

The 1950s were particularly difficult for Nikolai Simonovich, when central republican newspapers and magazines unleashed a barrage of criticism on his works:

- 1951 – “Vopreki zhizni,” “Zeleny klin,” “Neskolko zametok po romanu ‘Pishpek 1918 g.’;

- 1952 – “Vopreki zhiznennoy i khudojestvennoy pravde,” “O ‘kudrevatosyakh’ v sloge,” “Ser’yeznyye oshibki”;

- 1955 – “Roman ili khronika?,” “Semirechye”;

- 1956 – “O romane ‘Semirechye’ N. Chekmeneva;

- 1957 – “Moi pozhelaniya pisatelyu N. Chekmenevu,” “Udachi i neudachi pisatelya”...

From 1957, reviews of N.S. Chekmenyev's creativity became a little more benevolent. His name appeared in “Bibliographic Notes,” in collections “Writers of Soviet Kyrgyzstan,” biobibliographic indexes “Literature of Kyrgyzstan.”

And on November 23, 1961, an obituary appeared in the newspaper “Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan”: “Nikolai Simonovich Chekmenyev…”

Meanwhile, where else, if not in “Semirechye,” do we learn about meetings not in battles, but in “peace,” as they said then, of participants in those turbulent and anxious events: A. Ivanitsyn, P. Nagibin, Ya. Logvinenko. But let’s turn to the text:

“Ivanitsyn seated the guests at the table, and began to walk slowly from corner to corner of the small room. He was intently studying his interlocutors. From his speech, it was clear that he was a well-read person and cautious in decisions. Dressed in a kosovorotka, a woolen jacket, and trousers tucked into boots, with short-cropped dark blond hair, Alexey Illarionovich looked still young, but gray had already touched his temples, and deep folds lay between his brows and at his mouth. Before he spoke about what was troubling him at that moment, Ivanitsyn began to ask Nagibin and Logvinenko in detail about front-line affairs, about everything the soldiers saw and heard on their way to Semirechye…

- How to live, you say? – he asked again. – Well, Peter Yegorovich, we will forge happiness with our own hands. No one will give us a bright, free, and happy life; it will not fall from the sky; we must conquer it with our own hands.

Alexey Illarionovich approached the bookshelf, reached for a volume of Pushkin, then lowered his hand:

- I wanted to read you a poem, – he said, as if apologizing, – but I remember it by heart… What wonderful words! Just listen…

Comrade, believe, it will rise,

The star of captivating happiness,

Russia will awaken from sleep,

And on the ruins of autocracy

They will write our names.”

And they wrote… These people are inscribed in the history of the republic, in the city, their names are given to streets, they are immortalized in monuments. And it would be very bad if all this were “rewritten” according to the momentary trends of the new time and “new people.”

As for A.S. Pushkin… Rereading the novel “Semirechye,” I “met” the Poet and thought: “How Eternal he is! Is that why today we turn again and again to His Lyre, calling to ‘awaken kind feelings’?”

In the novel “Semirechye,” its heroes work, fight, love, and struggle for a bright future. Time passes, but universal human values are, in general, unchanged…

So here, in “Semirechye,” on one of the relatively calm days, friend Peter Nagibin goes to woo a bride for Yasha Logvinenko:

“Nagibin cleared his throat again and began:

- We are now living, one might say, well. We have everything: cabbage soup, porridge, bread, and water – our soldier's food.

And also, we have seven kinds of peas – fried peas, boiled peas, steamed peas, soaked peas, crushed peas, and peas in pies. In short, we have everything in the house, everything is stocked up, but there is no one to fry, steam, crush, or boil. So, my friend and I walked around the city, looking for a hostess. Everything is there, but no hostess.

And without a hostess, like without a host – the house is an orphan…

And then the wedding feast lasted several days. Maslenitsa passed in the thunder of the orchestra, in the ringing of the accordion and girls' songs. Daring troikas with bells rushed through the city…”.

I no longer remember why, but it so happened that about twenty-five years ago, I began writing small publications about Ya.N. Logvinenko. Now I conclude that this probably happened under the influence of the novel “Semirechye” and those monuments that remind us every day of the feats of days long past…

Recently, a collection titled “Ukrainians in Kyrgyzstan. Articles. Studies. Materials” (Bishkek, 2003) was published in the republic, which contains an article “Yakov Logvinenko as a Historical Figure.” To write an article about Yakov Nikiforovich Logvinenko – commander of the first Pishpek Red Guard regiment, I carefully studied collections of documents, archives, photo archives, and at one time talked with the son of Yakov Nikiforovich, Stanislav, and tried to create both in my consciousness and in the article the image of a truly historical figure. But more fully about an ordinary young man, fervently wishing to improve both his life and that of his contemporaries, can only be “read” in “Semirechye” by N.S. Chekmenyev, who, of course, knew the entire family of Yakov Logvinenko well.

In the prime of his talent, the remarkable writer N.S. Chekmenyev passed away. He was still nurturing new ideas, contemplating the plots of future books. On that November day in 1961, when Nikolai Simonovich left us, an unfinished manuscript of a new novel “Istra,” in which he narrates about the events of the pre-war years and the Great Patriotic War, remained on his desk.

Uncompromising, straightforward, honest, he lived openly, intensely, and boldly. Despite being a veteran of war and labor, a holder of the orders of the Red Star, “Sign of Honor,” having medals “For the Liberation of Warsaw,” “For the Capture of Berlin,” “For Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945,” “For Labor Distinction,” and a Letter of Commendation from the Supreme Soviet of the Kyrgyz SSR, he was essentially defenseless and easily wounded.

Contemporaries always believe that people like Nikolai Simonovich – soulfully rich, sensitive – need the least participation and support… They’ll manage their problems themselves!.. The list of publications by “professionals and non-professionals” in the periodical press regarding the writer's creativity: “About Kudrevatosy in the style,” “Against the truth of life,” “Wishes to the writer,” and others testify to the barrage of criticism and slander that Nikolai Simonovich's creativity was subjected to almost all post-war years… And yet he defended “Semirechye” with his very life. He endured because he was not alone! Every day, his friends – living and prototypes of the heroes of his written and conceived books – were beside him. “In the most difficult days for the writer, they always found warm, soulful words for him, knew how to support him with words and deeds, encourage and inspire him, helping him regain faith in himself, in his creative powers, so as not to retreat or stumble, to go further with more courage” (6). And he knew that even if “we cease to exist, Semirechye will continue to live.” And he continued to work…

And now the eternal theme of the struggle for its continuation is relevant: “Nastasya held on for a long time. She watched the departing squad for a long time and still could not hold back, brought her handkerchief to her face, covered her face with her hands, and stood for a long time, crying silently, biting her lips, until the last people of the squad disappeared from sight. And then she quietly went home, and a heavy thought, as lead, lay on her heart. ‘Curse the war! Who invented it?’…

Streams were running down the slopes of the Kyrgyz Ala-Too. The snow was melting, exposing the foothills; it retreated higher and higher to the cloud-capped peaks. In the valley, snowdrops bloomed, the grass turned green, cheerful larks sang. The roads dried after the rains.

From the east, a warm spring wind blew. Day and night, the wheels of carts and covered wagons thundered along the tract. The neighing of horses and the pounding of hooves could be heard. Day and night, soldiers marched to the Northern Front. Songs rushed along the tract, sometimes cheerful, sometimes sad. The chatter of people was unceasing, like the noise of a mountain river.

In the fields and gardens of the Chui Valley, bright spring bloomed. Ploughmen went out to raise new fields…”.

And the continuation was to follow…

Separate Editions

In Russian

Pastukh Sadyk (novella). – M.; L.: Gosizdat, 1929. – 64 p.

Sekty (novella). – GIKHL, 1931. – 115 p.

Zeleny klin (novella). – Frunze: Kyrgyzgosizdat, 1950. – 167 p.

Pishpek 1918 goda (novel). – Frunze: Kyrgyzgosizdat, 1952. – 184 p.

Semirechye (novel. Book 1). – Frunze: Kyrgyzgosizdat, 1954. – 382 p.

Kometa (novellas and stories). – Frunze: Kyrgyzgosizdat, 1956. – 235 p.

Semirechye (novel. Book 2). – Frunze: Kyrgyzgosizdat, 1958. – 412 p.

Translations

Into Russian

Bokonbaev Dzh. Zolotaya devushka (poem). – Frunze: Kyrgyzgosizdat, 1936. – 39 p.

Articles, Reviews, Essays

In Russian

Kubanychbek Malikov. – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – April 18, 1939.

Enthusiasts. – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – December 25, 1946.

Unforgettable Meetings. – Kazakhstan, 1950. – Book 23. – P. 121-124 (author's memories of Hungarian writer Mate Zalka).

Akyn-patriot. – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – December 15, 1950 (co-authored with T. Umetaliev).

Always Alive (Gogol and the works of Kyrgyz writers). – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – March 4, 1952.

In one state farm. – Frunze: Kyrgyzstan, 1952. – Book 1. – P. 116-120.

Kasymaly Bayalinov. – Komsomolets Kyrgyzstan. – June 10, 1952.

Creating an Image. – Frunze: Kyrgyzstan, 1953. – No. 3. – P. 95-102.

Builders of Orto-Tokoy. – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – April 17, 1955.

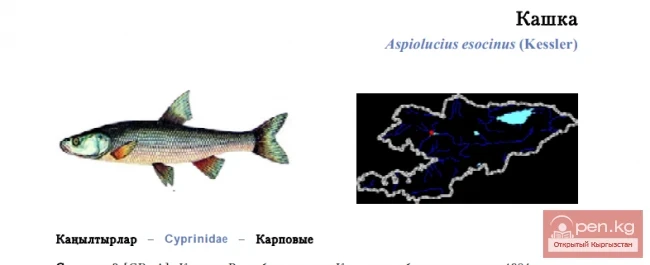

Fishing. – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – May 9, 1954.

About Stories. – Frunze: Kyrgyzstan, 1954. – Book 2 (20). – P. 103-105.

Stories about Kyrgyz literature. – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – September 11, 1954.

The Eighth River of Semirechye (from the writer's notebook). – Frunze: Kyrgyzstan, 1955. – No. 3. – P. 45-50.

New Wheat. – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – September 9, 1955.

In Kyrgyz

Akyn-patriot. – Kyzyl-Kyrgyzstan. – December 15, 1950 (co-authored with T. Umetaliev).

N.V. Gogol and Kyrgyz Literature. – Sovetikk Kyrgyzstan. – 1952. – No. 2. – P. 30-34; Zhas leninchi. – 1952. – No. 3. – P. 5-6.

Gogol and Kyrgyz Literature. – Leninchil zhash. – March 5, 1952 (co-authored with K. Eshmambetov).

Literature on Life and Creativity

In Russian

Tverskoy I. (Review of the novella “Sekty”). – Oktyabr. – 1932. – No. 5-6. – P. 259-260.

Zelenov V., Vayndorf M. and Bespalov M. Life Against. – Komsomolets Kyrgyzstan. – February 25, 1951.

Medovoy B. “Zeleny klin.” – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – April 10, 1951.

Morozov O. Several Remarks on the Novel “Pishpek 1918 goda.” – Komsomolets Kyrgyzstan. – May 18, 1951.

Medovoy B. Against Life and Artistic Truth. – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – October 31, 1952.

Yachnik E. About Kudrevatosy in Style. – Zvezda Vostoka. – 1952. – No. 2. – P. 105-111.

Aksakov M. Creating High-Ideological Artistic Works. – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – December 28, 1952.

Grishin P., Masadykov O. Serious Mistakes (participants of events about N. Chekmenyev's novel “Pishpek 1918 goda”). – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – November 23, 1952.

Vainberg I., Morozov O. A Novel or Chronicle? – Frunze: Kyrgyzstan, 1955. – No. 1 (22). – P. 64-76.

Vainberg I. “Semirechye.” – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – March 20, 1955.

Umetov Dzh. About the Novel “Semirechye” by N. Chekmenyev. – Works of the Institute of History (AN of the Kyrgyz SSR). – 1956. – Issue 2. – P. 97-108.

Baijiev M. My Wishes to Writer N. Chekmenyev. – Literary Kyrgyzstan. – 1957. – No. 2. – P. 125-128.

Vozheiko V. Successes and Failures of the Writer. – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – March 17, 1957.

Morozov O. Chekmenyev Nikolai Simonovich (Bibliographic Note). – Frunze, 1957. – 14 p. (State Republican Library of the Kyrgyz SSR named after N.G. Chernyshevsky).

Samaganov Dzh. Writers of Soviet Kyrgyzstan. – Frunze: Kyrgyzgosizdat, 1958. – P. 79-81.

Losev D.S., Morozov O.D. Literature of Kyrgyzstan. Biobibliographic Index. – Frunze, 1958. – P. 125-128. (State Republican Library of the Kyrgyz SSR named after N.G. Chernyshevsky).

Nikolai Simonovich Chekmenyev (obituary). – Sovetskaya Kyrgyzstan. – November 23, 1961.

In Kyrgyz

Nikolai Chekmenyev (Participant of the Decade of Kyrgyz Art and Literature in Moscow about himself). – Ala-Too. – 1958. – No. 9. – P. 99.

Samaganov Dzh. Writers of Soviet Kyrgyzstan. – Frunze: Kyrgyzgosizdat, 1958. – P. 69-71.

Nikolai Simonovich Chekmenyev (obituary). – Sovetikk Kyrgyzstan. – November 23, 1961.

Samaganov Dzh. Writers of Soviet Kyrgyzstan. Biobibliographic Reference Book. – Frunze: Kyrgyzgosizdat, 1962. – P. 432-436.

Notes

1. Valery Vakulenko. If we cease to exist, Semirechye will continue to live. A word about Nikolai Chekmenyev // Nikolai Chekmenyev. Semirechye. – Frunze, 1977. – P. 3.

2. The novella “Sadyk” by N. Chekmenyev was published in 1929 by the Moscow State Publishing House.

3. Nikolai Chekmenyev. Semirechye. – Frunze, 1977. – P. 4.

4. Pushkin A.S. History of Pugachev // Collected Works in 10 Volumes. – M., 1981. – Vol. 7. – P. 154.

5. Valery Vakulenko. “If we cease to exist, Semirechye will continue to live.” A word about Nikolai Chekmenyev // Nikolai Chekmenyev. – Semirechye. – P. 5.

6. Ibid. – P. 3.

Voropaev V. A.