Waste: the cycle from landfills to hospitals

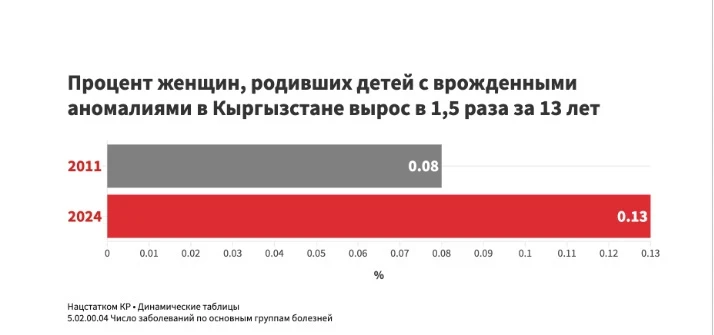

Improper waste management—from smoldering landfills to the toxic smoke of medical waste incinerators—not only pollutes the air in Kyrgyzstan but also becomes a personal problem for every family. Low waste recycling rates, such as incomplete burning of garbage or mixing organic and inorganic materials, lead to emissions of toxic substances and greenhouse gases. These substances contaminate the air, soil, and water.This pollution causes an increase in respiratory diseases and poses a threat of cancer, as well as reproductive health issues, especially for women and children. As health deteriorates, the demand for medical facilities increases, which, in turn, generates even more medical waste. Ultimately, a closed cycle is formed, where waste contributes to diseases, and diseases generate new waste. This also amplifies Kyrgyzstan's contribution to global climate change. This crisis, hidden from the public, begins at landfills and ends in the lungs of people, the wombs of mothers, and the air we breathe. According to the 2021 UNDP assessment of the medical waste management system in the Kyrgyz Republic, the infrastructure for medical waste disposal and data on this process remain inadequate.

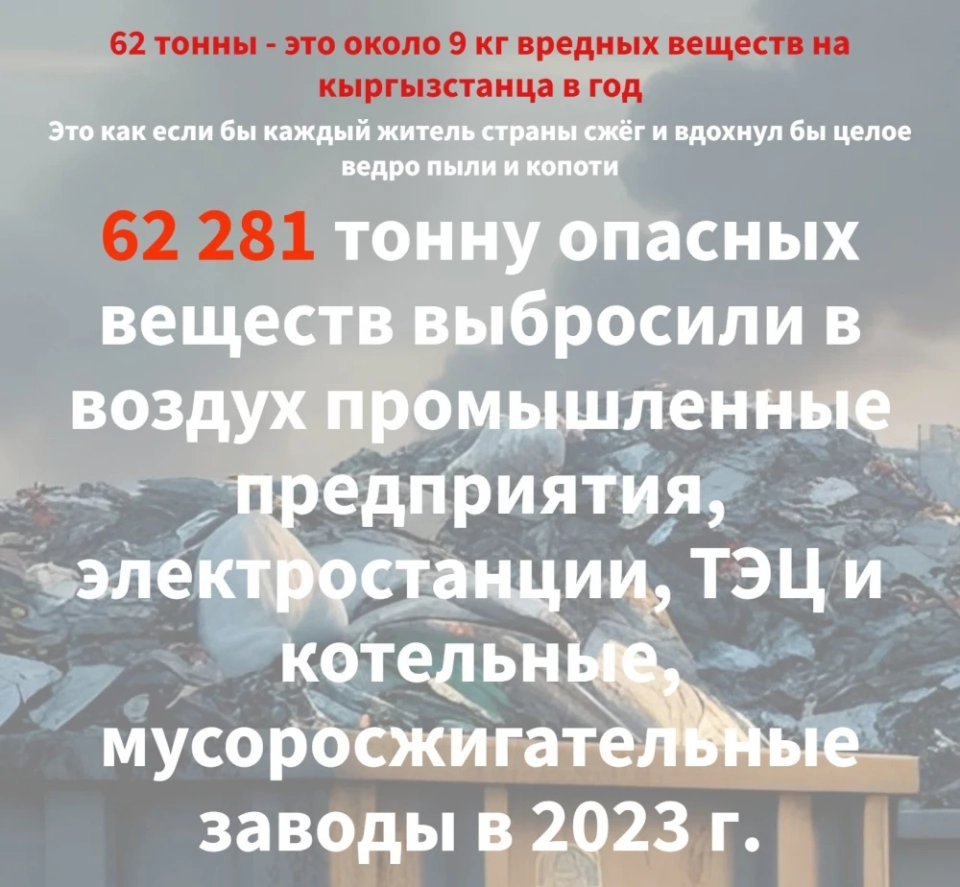

Medical waste is just one part of a broader pollution problem in Kyrgyzstan. While hospitals generate toxic waste in the treatment process, the diseases themselves are often a result of adverse environmental impacts. Factories, boiler houses, and vehicles emit hazardous chemicals into the atmosphere, negatively affecting health, especially among women and children. Air pollution from industrial sources not only exacerbates the ecological situation but also serves as another reason why public health and economic activity are in conflict.

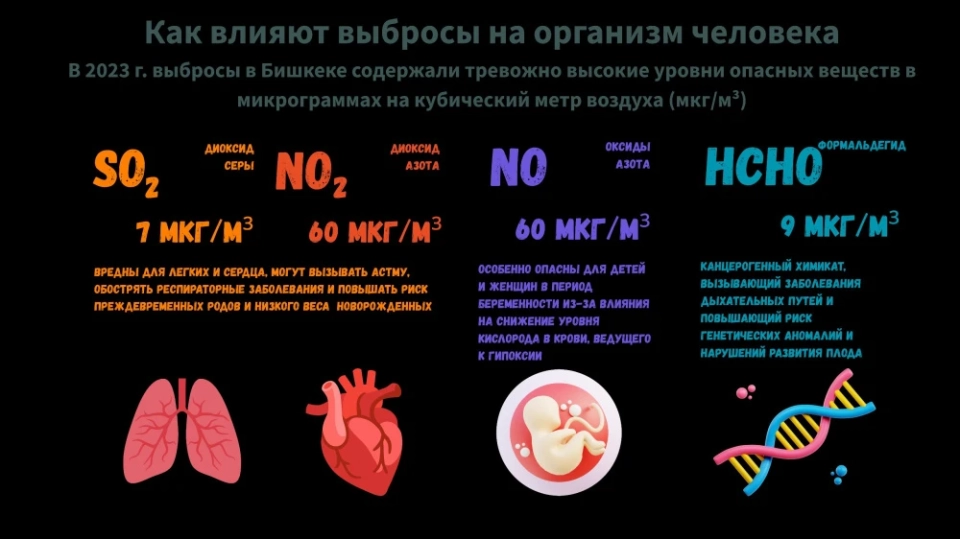

Emissions from industrial sources often contain harmful chemicals, such as sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and carbon oxides, which negatively impact women's health and fertility. These substances also increase the risk of respiratory diseases and cardiovascular diseases. Heavy metals and organic pollutants can disrupt the function of reproductive organs and lead to infertility.

Bakhtygul Bozgorpoeva, director of the Family Planning Alliance, notes: "Burning medical waste releases dioxins that pollute the air and pathogens that enter water bodies. These toxins return through food chains, water, and air, increasing the risk of cancer, infections, and endocrine disorders."

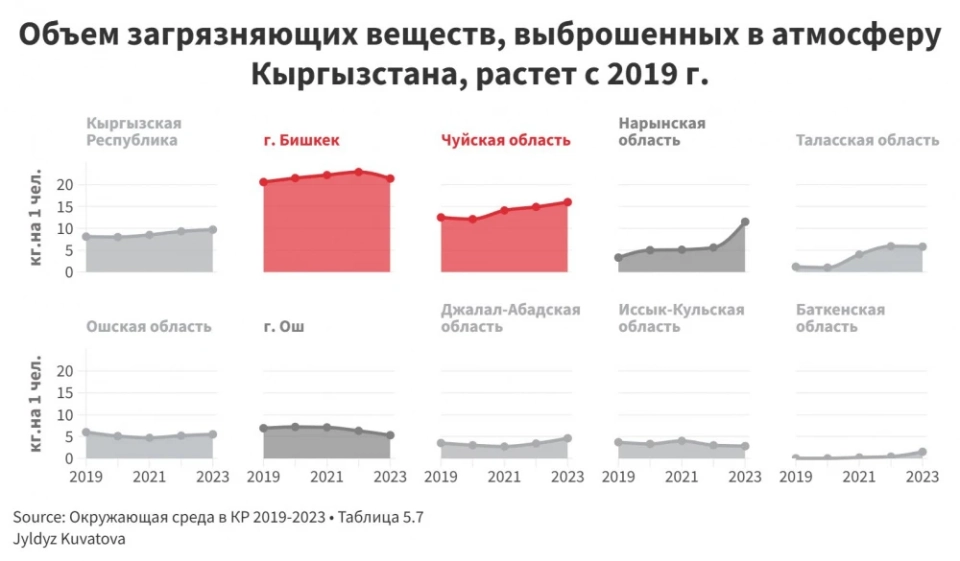

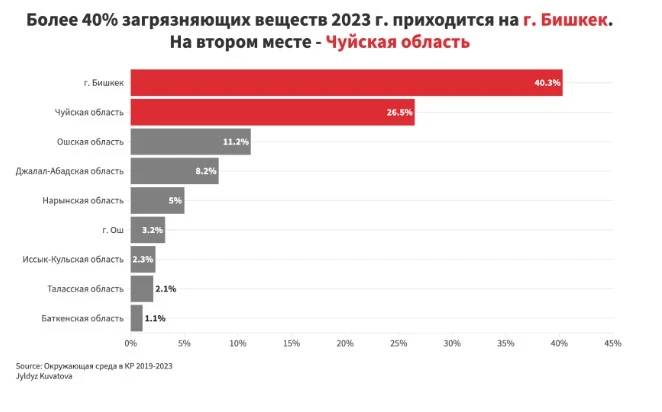

Research shows that in Bishkek and the Chui region, an increase in diseases among pregnant women and children is expected, as well as an increased likelihood of adverse pregnancy outcomes due to high concentrations of pollutants. In the Osh (11.2%) and Jalal-Abad (8.2%) regions, there is also an increase in diseases among women of reproductive age.

In 2023, the level of pollutant emissions per capita in Kyrgyzstan continues to rise.

There is also an increase in the incidence of bronchial asthma in regions with high pollution levels.

Breaking the vicious cycle of waste and disease is impossible without conscious actions. Measures are needed, starting from data collection and transparent accounting of medical waste. When information about air quality, waste, and the health of women and children becomes accessible and understandable, it can serve as a basis for action—from ministerial offices to clinics and local communities. Only then can Kyrgyzstan move from existing "in the fog" to a future where clean air and a safe environment become the norm, not the exception.

The author of the material is Yildiz Kuvatova, Associate Professor of the Department of Mass Communications at AUCA.