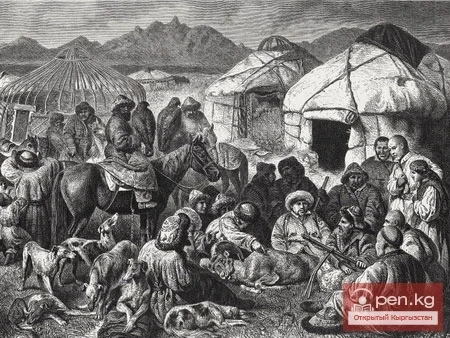

The Economy of the Kyrgyz in the 18th to Early 20th Century

Agriculture. According to the legislative acts of the Russian Empire, the lands of the indigenous population were declared state property, which had significant political implications. From the very first days of governing the region, the Russian government effectively began to act as the supreme landowner. The 1886 statute legally defined land relations of the indigenous population of Turkestan, reflecting the essence of land policy in Kyrgyzstan. Although the land was generally declared