Research on the issues of pre-Islamic beliefs among the Kyrgyz has always been of great interest and at the same time accompanied by difficulties for specialists. According to S.M. Abramzon, the study of the "complex of religious representations among the Kyrgyz, which is commonly referred to as 'pre-Islamic beliefs,' is characterized by particular complexity and multi-stage nature, conditioned by the peculiar and equally complex ethnic history of the Kyrgyz people."

Research on the issues of pre-Islamic beliefs among the Kyrgyz has always been of great interest and at the same time accompanied by difficulties for specialists. According to S.M. Abramzon, the study of the "complex of religious representations among the Kyrgyz, which is commonly referred to as 'pre-Islamic beliefs,' is characterized by particular complexity and multi-stage nature, conditioned by the peculiar and equally complex ethnic history of the Kyrgyz people." It should be noted that the historiography of this topic is quite extensive. Various aspects of the pre-Islamic beliefs of the Kyrgyz have been reflected in the works of scholars such as V.V. Bartold, V.V. Radlov, F.V. Poyarkov, S.M. Abramzon, A. Aitbaev, T.Dzh. Bayalieva, B.A. Amanaliev, I.B. Moldobaev, and others. Nevertheless, the Majesty of Time, the prospects for the development of historical and ethnographic science, and the needs of society urgently require progress and a reassessment of previously existing positions in the spirit of the times.

Therefore, the relevance of this topic is beyond doubt and does not require special proof. It is dictated by theoretical and practical necessity. It is known that an in-depth and comprehensive theoretical study of the essence and state of the religious beliefs of the Kyrgyz will help solve existing individual problems and practical tasks of our traditional Kyrgyz society. For example, authorities at all levels, deputies of the Jogorku Kenesh of various convocations, and the Muslim clergy have been trying for years to instill moderation and rationalism in the performance of various rituals, at least in accordance with the canons of Islam and Sharia.

However, as practice shows, the realities of our life yield little response, although some progress is observed. The process is slow and difficult, as the roots of extravagance lie in the folk, everyday Islam, in which elements of pre-Islamic forms of beliefs occupy a significant place, and studying its essence will help overcome this negative phenomenon. Or take another example, the problem of the Kyrgyz converting to other religions. This phenomenon can also be explained by the prevalence of folk, everyday Islam in the public consciousness of the Kyrgyz, precisely its amorphousness, looseness, and lack of formal structure both vertically and horizontally. In short, there are plenty of such problems in our society, the resolution of which depends on the degree and quality of research into the essence and state of religious belief.

As it seems to us, the formulation of the following questions and obtaining answers to them adequately reflects the content of our article. So, what do the religious beliefs of the Kyrgyz represent? What was the ancient pre-Islamic religious belief of the Kyrgyz? What is folk, everyday Islam? How is its syncretism expressed? Has there been a transformation of the pre-Islamic religious beliefs of the Kyrgyz, or has a peculiar religious system developed, and what is its current state? How should we relate to such a religious system: to fight against it, to overcome it, or should we preserve and encourage its development, etc.?

Thus, the Kyrgyz, as one of the oldest Turkic peoples, with an age of over two thousand years, have an ancient, rich, and multi-layered spiritual culture worthy of their considerable age. The ethnonym "Kyrgyz" in Chinese transcription "Jiangong"

is found in the work of the "father" of Chinese history, Sima Qian, "Shi-zi" – "Historical Records" (145-86 BC) in 201 BC. This work contains information about the existence of the Kyrgyz, who were conquered by the Huns.

Throughout their multi-century, multi-layered ethnic history, the Kyrgyz have been familiar with and practiced Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and Christianity to varying degrees. However, due to various circumstances, the Kyrgyz did not become convinced fire-worshippers, Buddhists, or Christians. Paradoxically, despite their venerable age, the Kyrgyz are still relatively "young" and moreover "poor" Muslims.

Why are the Kyrgyz, despite such a long ancient ethnic history, "young" Muslims compared to neighboring related Turkic peoples that appeared and formed later? There are many reasons for this, primarily the long dominance of nomadic pastoralism among the Kyrgyz, as well as the patriarchal structure and, of course, the extremely resilient and viable forms of such pre-Islamic beliefs as animism, totemism, fetishism, Tengriism, shamanism, and the cult of ancestors and the deceased, which, intertwining and coexisting with the orthodox positions of Sunni Islam, currently constitute the essence of the folk or everyday Islam of the Kyrgyz. In this peculiar blend, customs and traditions, various archaic syndromes existing at the subconscious level, as well as the peculiar mentality of the Kyrgyz, give their religious belief a syncretic character.

It should be noted that the pre-Islamic beliefs of the Kyrgyz still make themselves known today, although they are gradually being pushed to the background, constantly influenced by Islam and progress. In short, there is a completely natural process of the gradual absorption of the old by the new, archaic forms of belief adapting and entering into a synthesis with the new religious system.

Regarding the religious views of the ancient Kyrgyz, based on scant data from written sources, it can be said that totemistic worldviews were typical of that time as one of the earliest manifestations of religious beliefs. Among the Kyrgyz, as a people with a developed tribal structure, the ideas of blood kinship of the totem with a specific clan were transferred to the tribe. A vivid example of tribal totemism can be considered the belief in the origin of the large Kyrgyz tribe Bug from a deer. Another echo of the totemic worldview of the Kyrgyz in the past is the name of another large tribe, closely related to the Bugis, the Sarybagysh (yellow elk).

Furthermore, some subdivisions of Kyrgyz tribes bore names such as kiyik-nayman, kuran-nayman, which evidently reflected totemistic views associated with kiyiks. Kiyik or kayip (mountain goat, mountain ram, roe deer) were considered divine animals. The epic "Manas" is literally saturated with lines that speak of Kayberen – the patron of wild animals. The plots related to the ideas of the totem-kiyik have firmly entered and significantly enriched the life, folklore, and spiritual culture of the Kyrgyz. It is enough to mention the famous epic poem "Kozhozhash," as well as the poem "Karagul Botom," the legend of the progenitor of the tribal group Sayak – Kaba, and others.

It can also be noted that the Kyrgyz have many legends that contain stories about certain tribes or an entire nation descending from a dog and a wolf. Ideas related to the cult of the dog are found among the Mongols and Turkmen. It is no coincidence that in the epic "Manas," the hero's beloved dog – Kumayik is the most frequently mentioned animal.

The bürü (wolf), like its counterpart the dog, occupies a special place in totemistic representation not only among the Kyrgyz but also in world history. For example, the founders of Rome, the brothers Remus and Romulus, were suckled by a she-wolf (the Capitoline Wolf). The wolf also appears as a totemic ancestor in the legends and traditions of Anatolian Turks, Chechens, and many other peoples. The wolf is perhaps the universally recognized totem among the Turks. According to legend, the Turks descended from a she-wolf and a ten-year-old boy. Similar legends exist among the Usuns, Mongols, and others. One subdivision of the Kyrgyz tribe Adigine is called bürü, and within the tribes Kuschu and Solto, there are clan divisions named aksak-bürü (lame wolf). It is likely that the names of these tribes also have totemic roots. In the representation of the Kyrgyz, bürü acted as a protector of people from diseases, misfortunes, and all evil. The skin and various body parts of the wolf (even saliva, teeth, kneecaps, stomach, bile, tendons, etc.) were used for various purposes: as an amulet, a protection from evil spirits, the evil eye, in the treatment of diseases, etc.

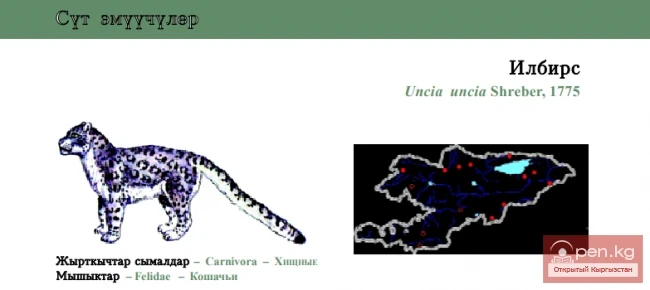

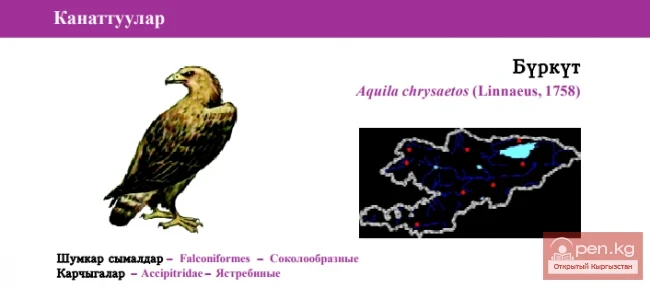

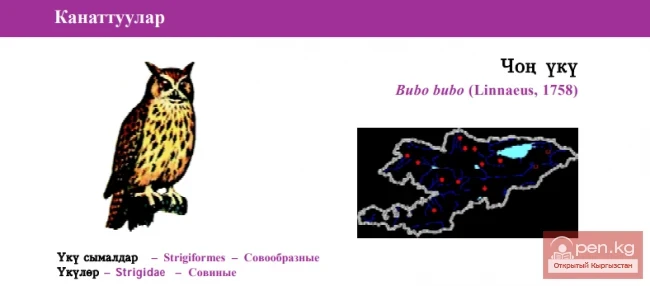

Among the Kyrgyz, beliefs and rituals related to the snow leopard, lion, tiger, golden eagle, owl, and other animals are also widespread. These data are confirmed in written sources. Thus, Gardizi in "Zayn al-Akhbare" ("Decoration of News," 11th century) writes that "some of the Kyrgyz worship cows, others – the wind, third – hedgehogs, fourth – magpies, fifth – falcons, sixth – beautiful trees."

Stone inscriptions also testify to the existence of totemistic representations among the ancient Kyrgyz related to the snow leopard. Thus, the monument "Berge" states: "I killed seven wolves. I did not kill snow leopards and deer." In many places of the runic inscriptions of the Kyrgyz, the snow leopard is mentioned, which is referred to as the founder of the clan. From the example of the epic "Töştük," one can judge what place animals occupied and what role they played in the life of Kyrgyz nomads, where 57 names of representatives of the animal world are used as similes. The total number of such comparisons in the text (taking into account repetitions and variations) is about 140.

Just listing the tribes and clans from the tribal grouping of the Kyrgyz that bear the names of various species of animals would take up quite a bit of space in this work.

However, totemism among the Kyrgyz essentially did not form an independent form of religious beliefs. It was closely linked with animism. Totemism universally intersects with the cult of ancestors through the female line and the cult of natural phenomena. Thus, the female, maternal cult – matriarchy – is distinctly felt in the veneration of the patroness of offspring, as well as the goddess of fertility Umay. The authority of Umay-Ene was so high that certain rulers associated their honorary title with the name of this unreal being.

The cult of nature was also an essential element of the religious beliefs of the ancient Kyrgyz. Among them, the cult of Earth and Water was widespread. The veneration of Earth and Water was likely based on the fact that they served as carriers of the life principle.

The supreme deity of the ancient Turkic pantheon is Tengri (Sky-Tengri) – the deity of the Supreme world. It is Tengri, according to the beliefs of the Turks, who governs everything that happens in the world and, above all, predetermines the fates of people. Tengri is the bearer of the masculine principle. Tengri "distributes the terms of life," however, the birth of "human sons" is overseen by Umay, and their death by Erlik. Tengri grants wisdom and power to khans, bestows khans upon the people, punishes those who have sinned against the khans, and even, "commanding" the khan, resolves state and military affairs. Another deity was Umay, the goddess of fertility and protector of newborns, embodying the feminine principle. The very word umay is associated with meanings such as "child's place," "womb," "uterus." Erlik – among the ancient Turks is represented in the most sinister image, that is, as the lord of the underworld. Idok Yer-su – the deity of earth and water belonged to the middle world. Judging by ancient Turkic texts, Yer-su (Zher Suu) was endowed with benevolent and punishing functions, sometimes it appeared in the meaning of Homeland. The cult of Yer-su was accompanied by the cult of mountains.

The above scheme or three-tiered hierarchy of deities of the ancient Turks (supreme deity of the Upper world – Tengri; Middle – Yer Su; Lower – Erlik) is quite applicable to the Kyrgyz as well. Even today, one of the synonyms for the concept of God (Allah, Kudai) is – Tengri. Such expressions as: "Tengri koldoy kör!" (Oh, Sky help!) are widely encountered; it is noteworthy that at one time the walls of many institutions were adorned with the poster "Tengrim koldosun, Kyrgyzstan!" (May Tengri bless you, Kyrgyzstan!)

S.M. Abramzon provides data from the famous dictionary of K.K. Yudakhin, where the word теңир is used instead of кудай or as a pair to it; sometimes together with асман or көк.

The Kyrgyz beliefs directed towards the deities Tengri and Yer Suu can be supplemented by ideas about celestial bodies and the elemental forces of nature. Ch.Ch. Valikhanov, who visited among the Kyrgyz, wrote that: "Fire, the moon, and stars are objects of their worship." He also observed the threefold earthly bows of the Kyrgyz upon seeing the new moon. F.V. Poyarkov also notes: "Upon seeing the moon, every Karakirgyz makes a bat (i.e., utters a prayerful wish), both men and women."

In the system of ancient religious beliefs of the Kyrgyz, special attention was given to the worship of celestial bodies. A. Baybosunov in his well-known work "Pre-scientific Representations of the Kyrgyz about Nature" (based on extensive factual material) noted that considerable attention is given to the sky, sun, moon, and other celestial bodies. They were endowed with mysterious power, influencing human life. Their positions determined the time of migrations, harvests, the laying of winter pens for livestock, the beginning of military raids or journeys to distant lands, etc.

The ancient Kyrgyz were unable to explain many natural phenomena and deified celestial bodies and mysterious processes occurring in the heavens; for example, many shining celestial bodies were transformed into кудай-god and his apostles. Lunar and solar eclipses, the movement, "wandering" of planets in the sky – all this was attributed to the influence of supernatural forces.

Thus, in the pagan period before the advent of Islam, the Kyrgyz worshipped the sun. In venerating the sun, the Kyrgyz washed themselves before its rise to meet it clean. It was forbidden to look long at the moon and the sun. In a medieval anonymous Persian-language work "Kitab Hudud al-Alam min al-Mashrik ila-l-Maghrib" ("Book of the Limits of the World from East to West," 10th century), it is written about the Chigils, who later became part of the Kyrgyz, that "some of them worship the sun and stars; they are good, sociable, and pleasant people."

A. Baybosunov writes that the Kyrgyz also deified the moon. Upon seeing the new moon, they made bows, apparently associating this moment with a change in life for the better, and in summer, they would take grass from the place of worship and, upon returning home, burn it. This custom traces back to the ancient cult of fire, preserved since the era of pagan beliefs among the Kyrgyz.

From the author's personal observation, rituals of moon worship still exist and are preserved among the Kyrgyz. For example, during the full moon, people bow while voicing their wishes and dreams. I have witnessed a scene where a new banknote of a large sum was brought out and raised to show it to the moon during the new moon to attract money. I remember when I was little, my late grandmother would remove warts from my hand. She would take a handful of grains in her palms and, bringing them to her lips, would recite a prayer from the Quran, also mentioning the names of Umay-Ene and Ulukman-Ata. Then, with this grain wrapped in gauze, she would rub the necessary places on my hand and, showing it to the moon, would bury it on the riverbank. How surprised I was when, after some time, the warts completely disappeared without a trace.

The mounds (mazars) are considered sacred by the Kyrgyz, which later became an integral part of everyday Islam, especially the cult of saints. Such mazars-shrines were scattered throughout Kyrgyzstan. For example, among such mazars are the famous Arslanbob (in the south of the republic), Karakol-Ata (on the bank of the Karakol River, near the city of Karakol), Shyng-Ata (on the northern shore of Lake Issyk-Kul, near the agricultural college in the village of Svetly Mys), Manzhyly-Ata (600-700 m from the road, a few km from the Kekilik River, on the southern shore of Issyk-Kul), Cholpon-Ata (a well-known mazar, on its possible location a complex has now been built in honor of the eponymous saint), Kochkor-Ata (Kochkor Valley), etc.

In the system of religious beliefs of the Kyrgyz, there was also a cult of fetishes (ongon). However, such veneration, which had images or appeared in the form of idols, figures of gods, was completely forgotten, as they were considered the worst form of "shirk" and were severely persecuted with the introduction of Islam. In the hagiographic work "Ziya al-Qulub" ("Radiance of Hearts"), written by an unknown author in 1012/1603, the process of Kyrgyz prayer to their idols in the sanctuary (but khana) is described in detail. When the Sufi sheikh Khoja Iskhak and his followers came to the Kyrgyz, they prayed in the but khana for the health and healing of their sick leader Seriyuk. An idol (but) made of silver hung from a tree, and around it were about two thousand other idols carved from wood and stone, and this was the sanctuary of the Kyrgyz. They brought food there, and each of those sitting would cut off a piece of meat and throw it into a vessel. The vessel was taken to the idol, they bowed towards it and bowed before it. They made signs to the large idol to taste this food. Then the vessel with meat was moved away, one piece of meat was placed in the left hand of the idol, another in the right, and a third piece (crumbled) was scattered.

According to the source, Khoja Iskhak healed the sick man, and all those present became Muslims. After that, all the idols were smashed, and the silver was given to the close associates of the sheikh.

The term "but khana" is also used in the epic "Manas," especially often in episodes that talk about the adventures of Koshoy. Unraveling the meaning of the concepts "but" and "but khana," the well-known manas scholar I.B. Moldobaev suggested that they are a consequence of the Kyrgyz's acquaintance with Buddhism. In his opinion, the description of the idol in the epic "Manas" approaches the characteristics of Buddhist monuments.

The cult of the deceased and ancestors occupied a prominent place in the system of pre-Islamic beliefs among the Kyrgyz. The spirits of deceased ancestors are called arvaq. According to the beliefs of the Kyrgyz, every person has a jan (soul), which exists in the form of chymyn (fly). The soul was also represented by the Kyrgyz in the form of a blue smoke (kök tüntün), which supposedly the dying person emits with their last breath.

Ideas about the spirits of the deceased and ancestors arose among the Kyrgyz long before their acceptance of Islam. The spirits of the deceased also played an important role in the life of nomads, and candles were lit in their honor, and rams were sacrificed. In difficult life situations, the Kyrgyz called upon and addressed the spirits, naming the names of their ancestors, and performed worship at their graves.

It is necessary to note that the peculiar memorial rituals of the Kyrgyz reflect a combination of various views, rooted in antiquity, animistic ideas, based on the belief in the existence of the soul and its afterlife. Indeed, the burial cult belongs to the number of the oldest forms of religions, which reflects the aggregate of beliefs and rituals of the Kyrgyz associated with the deceased and their burial. In the burial cult of the Kyrgyz, local traditional elements are felt and prevail from all sides of religious life, which are still much stronger than the traditions of Islam. Although some elements of these rituals were adopted by Islam, underwent changes, or were reinterpreted in a Muslim spirit, they still remain quite stable today.

A telling testament to the resilience of the cult of ancestors and the deceased can be considered the widely resonant brochure by former deputy of the Legislative Assembly of the Jogorku Kenesh of the Kyrgyz Republic, former Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Kyrgyzstan to Belarus and Ukraine R. Kachkeev, "Arbakhtar süylöyt" – "The Arbakhtar (souls of deceased ancestors) speak." The author of the sensational brochure seriously claimed that through mediums he had contacts with the deceased and spoke with them. Among the spirits he managed to communicate with were the spirits of almost all known Kyrgyz people throughout history, as well as the spirits of Stalin, Napoleon, Brezhnev, and others.

One of the earliest forms of religious belief among the Kyrgyz was shamanism. There is an opinion that the archaic mythical worldview, religious beliefs, and ritual practices of the Turks, including the Kyrgyz, were formed on the basis of shamanic rituals. It is based on the belief in the communication of the shaman, who is in a state of ritual ecstasy (kamlanie) with spirits.

In the ancient Chinese source "Tang-shu," Kyrgyz shamans are called gan (kam). The 11th-century author Gardizi in "Zayn al-Akhbare" writes about "faginuhs" among the ancient Kyrgyz, who, while performing ritual music, lost consciousness, and when they came to, predicted everything "that would happen that year: about need and abundance, about rain and drought, about fear and safety, about the invasion of enemies." Here, undoubtedly, we are talking about shamans. As can be seen from these lines, shamans were versatile, extraordinary people. Ch.Ch. Valikhanov wrote about shamans that they were revered as people protected by heaven and spirits. A shaman is a person endowed with magic and knowledge above others; he is a poet, musician, prophet, and at the same time a healer. In short, shamans could do many things. F.V. Poyarkov noted that shamans were capable of licking a heated sickle or knife with their tongues, standing barefoot on the bottom of a hot cauldron, swallowing two or three dozen live snakes, allowing several people to pull them with a rope, and performing many tricks in the same spirit. I.B. Moldobaev, considering the practice and abilities of Kyrgyz shamans, drew parallels and found many similarities with the teachings and training of Indian yogis.

The Kyrgyz called a shaman bakshy, and women shamans were called bübü-bakshy. Two categories of shamans were distinguished: black shamans (kara bakshy) and white shamans (ak bakshy). Black shamans were considered more powerful, as they could not only heal the sick by driving out evil spirits from the body but also, if desired, send them to other people. Shamans became shamans by coercion, after illness, and also by inheritance. Shamans treated the sick with the help of their spirits. There were three types of spirits: guardian spirits, helper spirits, and jinn spirits. The first two helped the shaman in healing or performing other deeds, while the third caused harm to the sick and was the main object of the shaman's influence.

The spirits took on various forms: flies, camels, calves, snakes, frogs, humans, etc. With the penetration of Islam, shamans began to adopt and use Muslim terminology, names of saints and shrines, etc. Healing sessions ended with prayers from the Quran. Sufism had a significant influence on the development of shamanism.

The Kyrgyz also recognized fire as an object of worship, which was revered not as a deity but as a sacred element. It purified a person. According to Gardizi in "Zayn al-Akhbare," the Kyrgyz, like Hindus, burn the dead and say: "Fire is the purest thing; everything that falls into the fire is purified."

In the anonymous 10th-century source "Kitab Hudud al-Alam min al-Mashrik ila-l-Maghrib" ("Book of the Limits of the World from East to West"), there is a very scant report that the Kyrgyz worshipped fire and burned the dead. Academician V.V. Bartold, interpreting this data, wrote that "the information about the burning of the dead is confirmed by the Chinese; moreover, the Chinese say that after a year, the bones remaining after the cremation of the corpse were buried in the ground; unlike the Turks, they did not scratch the faces during funerals."

Before the advent and spread of Islam, the territory of Tian Shan, Semirechye, and Fergana in the early Middle Ages, like all of Central Asia as a whole, was the arena of intense competition among different religious systems of that time. Here, Zoroastrianism and Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, and Manichaeism clashed and competed with each other. Each of these religious systems had its cult structures and a well-defined organization. The missionary activities of the mentioned religious systems in the 6th-10th centuries had only partial successes among the population of Kyrgyzstan. None of them could become the official state religion on its territory during the dominance of Turkic khanates.

Islam emerged as a new and more progressive stage in the hierarchy of religious beliefs of the Kyrgyz. Such important questions as the time, stages, and paths of the spread of Islam in Kyrgyzstan remain poorly studied and controversial. However, the study of the topic of Islam is not included in the tasks of our article and is the subject of a separate, serious discussion. As for this article, an incomplete overview of the pre-Islamic forms of religious beliefs of the Kyrgyz shows that they have ancient origins and are very complex in composition. After the penetration of Islam, their transformation occurred with Islam, becoming to a certain extent a part of it. As one of the leading specialists in religion S.A. Tokarev rightly noted, "Any form of religion can merge into the composition of the religious beliefs of a particular people, into a complex religion, and become its component, its element. This is analogous to how the remnants of past socio-economic formations can be preserved in a society where a higher type of social relations prevails..."

In conclusion, it can be said that among the Kyrgyz, under the influence of pre-Islamic forms of beliefs, a syncretic religious belief called folk, everyday Islam has formed. Thanks to such Islam, we are free from fanaticism, obscurantism, and extremism. Our "signature" folk, everyday Islam is the main prerequisite for tolerance.

NOTES:

Abramzon S.M. Kyrgyz and their ethnogenetic and historical-cultural connections. – Frunze, 1990. – P. 291.

Bichurin N.Ya. (Iakinf). Collection of information about the peoples that inhabited Central Asia in ancient times. – M-L., 1950. Vol. 1. – P. 350-355.

Dushenbiev S.U. Syncretism of Kyrgyz Islam in a polyconfessional society // Buddhism and Christianity in the Cultural Heritage of Central Asia: Materials of the International Conference, Bishkek, October 3-5, 2002. – B., 2003. – P. 253-255.

Abramzon S.M. Op. cit. – P. 297-307; Amanaliev B. Pre-Islamic beliefs of the Kyrgyz // Religion, free thought, atheism. Frunze, 1967. P. 19-20; Bayalieva T.Dzh. Pre-Islamic beliefs and their remnants among the Kyrgyz. – Frunze, 1972; Dushenbiev S.U. Religious beliefs. – In: Kyrgyzstan. Encyclopedia. B., 2001. P. 267-275.

Bartold V.V. Excerpts from Gardizi's work "Zayn al-Akhbar." Work. M., 1973. – Vol. VIII. – P. 48.

Dushenbiev S.U. Religious beliefs... – P. 268.

Klyashtorny S.G. Mythological plots in ancient Turkic monuments. In: Turkological Collection. 1977. – M., 1981. – P. 131-133; Amanaliev B. Pre-Islamic beliefs of the Kyrgyz... – P. 19-20.

Abramzon S.M. Op. cit. – P. 309.

Valikhanov Ch.Ch. Collected works in 5 vols. Alma-Ata, 1961. – Vol. 1. – P. 370.

Poyarkov F.V. Kara-Kyrgyz legends, tales, and beliefs. Commemorative book and address-calendar of the Semirechye region for 1900. – Verny, 1900. – P. 32.

Baybosunov A. Pre-scientific representations of the Kyrgyz about nature. – Frunze, 1990. – P. 58.

Materials on the history of the Kyrgyz and Kyrgyzstan. M., 1973. Issue 1. P. 43.

Baybosunov A. Op. cit. – P. 46.

Abramzon S.M. Op. cit. – P. 320-321.

Ziya al-Qulub. In: Materials on the history of the Kyrgyz and Kyrgyzstan. – M., 1973. – Issue 1. – P. 182-184.

Moldobaev I.B. The epic "Manas" as a source for studying the spiritual culture of the Kyrgyz people. Frunze, 1989. P. 71.

Bayalieva T.Dzh. Pre-Islamic beliefs and their remnants among the Kyrgyz. Frunze, 1972.

Kachkeev R.O. Arbakhtar süylöyt. – B., 1997.

Bichurin N.Ya. (Iakinf). Op. cit. P. 353.

Bartold V.V. Op. cit. P. 48.

Poyarkov F.V. From the field of Kyrgyz beliefs. // Religious beliefs of the peoples of the USSR. – M-L., 1931. Vol. 1. P. 268.

Moldobaev I.B. Op. cit. – P. 71-72.

Bayalieva T.Dzh. Op. cit.

Bartold V.V. Kyrgyz. Historical essay. In: Selected works on the history of the Kyrgyz and Kyrgyzstan. – B., 1996. – P. 199.

Hudud al-Alam. In: Materials on the history of the Kyrgyz and Kyrgyzstan. Edited by V.A. Romodin. M., 1973. Issue 1. P. 41.

History of the Kyrgyz SSR. From ancient times to the mid-19th century. – Frunze, 1984. – Vol. 1. – P. 320, 370-374.

Tokarev S.A. Early forms of religion. – M., 1964. – P. 40.