Left a Name for Future Generations and a Street

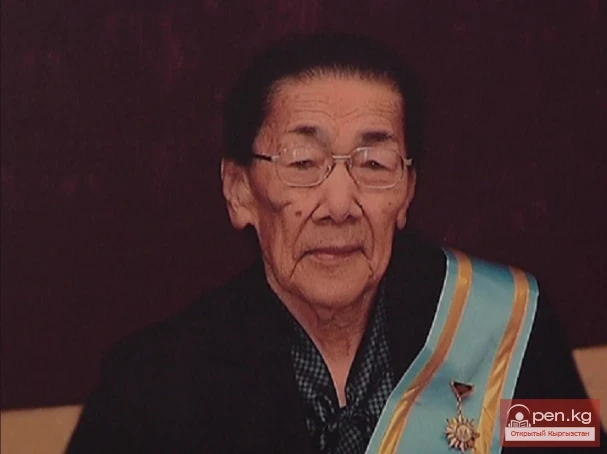

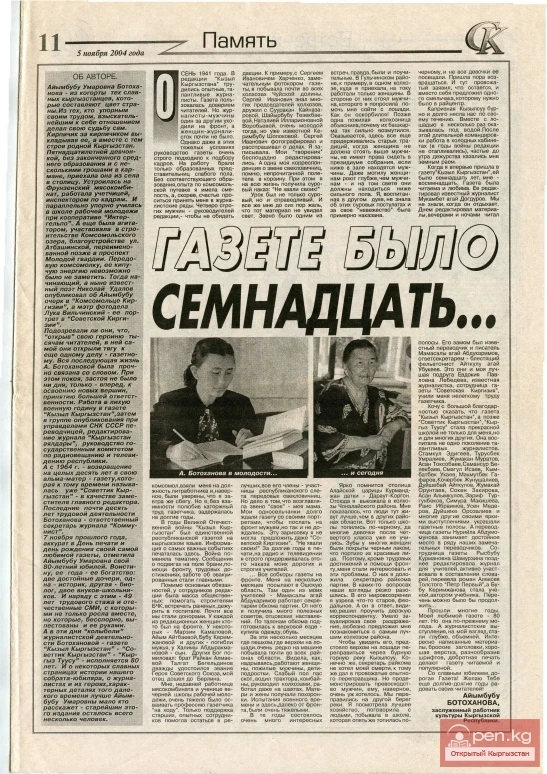

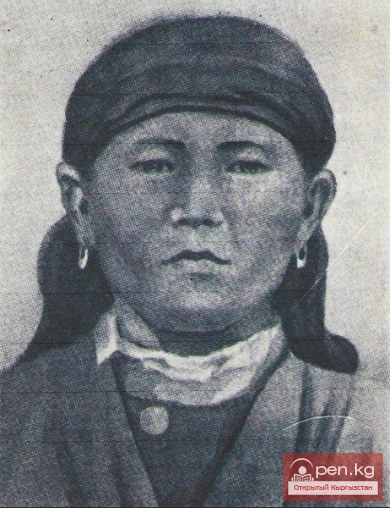

Tursun Osmonova was one of the first active participants in the movement for the emancipation of Muslim women in the East and the first female Minister of Social Welfare in Kyrgyzstan. She was affectionately known among the people as Tursun-apa.

Tursun Osmonova was born in the village of Uch-Uryuk in the Kemin district in 1900 into a poor family. Her mother died during childbirth, and a year and a half later, her father passed away. From the age of seven, she performed various household chores for others. At 13, she was married off to a postal carrier from the Kok-Moynok station. With her husband, she began delivering mail.

In 1916, she fled to China with the people, and in 1917, she returned to the city of Tokmok.

The October Revolution dramatically changed Tursun's fate. She was one of the first Kyrgyz women to work in a food brigade, sewing and collecting warm clothing for the fighters of the Red Army, and conducting extensive educational work among women laborers and peasant women, involving them in public life. Voluntarily joining the ranks of the Red Army, she served as a nanny and nurse in the 12th Turkestan Rifle Regiment. She participated in the fight against the Basmachis as part of the 4th Tatar Brigade in southern Kyrgyzstan and was wounded. She was fluent in Russian, Uzbek, and Tatar.

After the end of the Civil War, in 1923, T. Osmonova organized a Komsomol-party cell in the city of Tokmok and worked as a women's organizer in the district party committee. She actively worked on creating production cooperatives, women's schools to eliminate illiteracy, and children's nurseries and kindergartens.

In 1924, she was one of four activists from Kyrgyzstan who traveled to Moscow to celebrate International Women's Day, where she met with Lenin's close associate and wife, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya. She visited Moscow again in 1930, where she met with the prominent figure of the international women's movement, Clara Zetkin. During her meetings in Moscow with N. Krupskaya and M. Frunze, T. Osmonova spoke about life in Kyrgyzstan, her work, and the situation of women.

In 1925, Tursun joined the ranks of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). The communists of Tokmok elected her as a delegate to the First Regional Congress of Peasant Women, Laborers, and Farmers of the Kyrgyz Autonomous Region. Together with the delegates of the congress, T. Osmonova supported the demands for the opening of schools for girls and women, maternity and medical points, red corners, women's clubs, and courses for training teachers from local nationalities, and called for a decisive struggle against bride price, early marriages, and the forced marriage of girls and women. The First Congress of Women of Kyrgyzstan, held in the capital of the republic from March 5-8, 1925, was marked by extraordinary enthusiasm. It played a significant role in awakening a sense of dignity and belief in a new happy life among women.

From 1926 to 1929, T. Osmonova worked as the deputy head of the women's department of the KirObkom party, and later as the head of the Osh district women's department. She dreamed of seeing Kyrgyz women liberated from the burdens of the old way of life.

At the Third Regional Party Conference in 1927, she expressed with pain: "We have existed under the new government for 10 years, but during these years we have not been able to involve women in active public life, nor have we been able to enlighten them. It is not enough to recognize that all women are uneducated; a large part of them is in a state of slavery. From this follows the gigantic task of fighting for the education of women. Everyone needs to send their women to meetings, involve them in delegate congresses, literacy courses, and other political institutions of ails and kishlaks... The struggle for the emancipation of women, work among women is limping."

It was a difficult time. Just consider the "hujum" - the movement against the burqa in southern Kyrgyzstan. Killed, torn apart, mutilated... The fierce resistance of the "class enemy" simply intoxicated by the customs of adat cost the lives of hundreds of women. Bolshevism ignored folk customs and traditions, trampling over moral and ethical norms... The haste and pressure caused a negative attitude among the majority of the indigenous population towards the movement for the emancipation of women.

At the same time, the Kyrgyz people had customs that required immediate revision. In 1921, the Turkestan Republic enacted a law abolishing bride price and raising the marriage age, prohibiting polygamy and the forced marriage of girls. But, as often happens in life, the implementation of the law was slow.

In 1930, T. Osmonova was appointed the People's Commissar (Minister) of Social Welfare of the republic. In 1931, she completed courses on Soviet construction in Moscow and worked as the deputy People's Commissar of Education of the Kyrgyz ASSR. From 1927 to 1933, she was a member of the KirObkom party and the regional executive committee, and later a member of the Central Executive Committee of the Kyrgyz ASSR.

In 1927, she was a delegate to the XIII Congress of the Soviets of the RSFSR and the IV Congress of the Soviets of the USSR.

Until she retired in 1953, she held responsible positions in the Soviet and economic bodies of the republic and was actively involved in public activities.

Her contributions were highly valued by her homeland. She was awarded the Order of Lenin, the Order of the Red Banner of Labor, the "Badge of Honor," and various medals. In her last years, she lived alone in Bishkek. Her husband was a pilot who died while on duty. Her son died in the Great Patriotic War. She passed away on December 20, 1970.

Her contribution to the development of the women's movement in Kyrgyzstan is immense. And her memory lives on. Grateful fellow countrymen named one of the streets in the Kichi-Kemin rural council after Tursun Osmonova.

Women of Kyrgyzstan