Legends about the "Burana Tower"

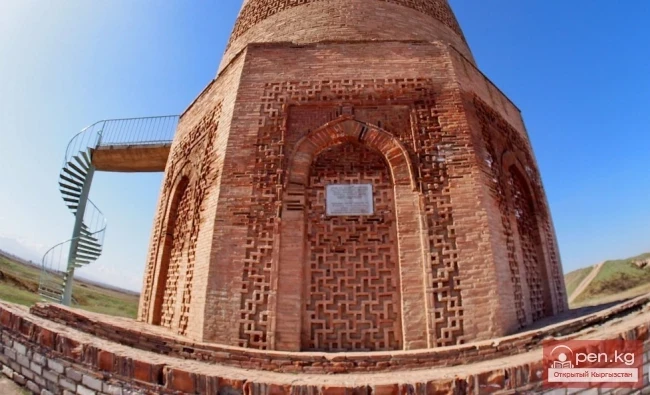

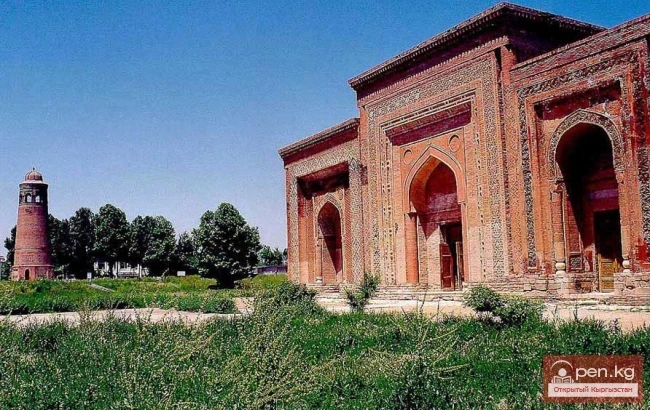

The term minaret, widely used in European contexts, originates from the Arabic word minar (a place where something is lit — a lantern, lighthouse) or miiara (a watchtower, pillar, minaret of a mosque). In the latter sense, in local pronunciation among Tajiks and Uzbeks, it is meiaré, and among some Turkic ethnic groups in Central Asia, it is men ar. Among the local population living in the former northern Kyrgyz region of Jeni-Su (Semirechye), and in contemporary scientific literature, this word is used in the form of burana, which undoubtedly reflects a linguistic peculiarity of the Kyrgyz language. In this form, the term has become a geographical name for an unnamed medieval settlement located in the southeastern part of the Chui Valley, at the foot of the Kyrgyz Ala-Too ridge (or Ala-Tau, formerly known as the Alexandrovsky ridge), 11 km southwest of Tokmak. It has also become a proper name for the ruins of a large medieval minaret located within this settlement and for the river flowing around the settlement from the east, which is a left tributary of the Chu River.

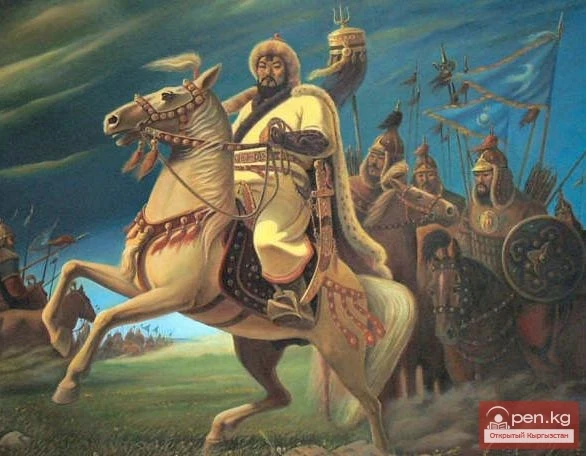

In some works by Arab authors from the 9th to 10th centuries, who wrote about Central Asia, there are many names of various settlements and even significant cities that existed at that time in Semirechye. After the 10th century, the information from Muslim writers about the Chui Valley becomes more vague, with names of places given without precise indications of their mutual locations or distances between them. Their existence was mainly interrupted shortly after the Mongol conquest, largely due to the change in population, and the former names of numerous deserted ruins became firmly forgotten. At present, it is often difficult to establish which archaeological object corresponds to a particular name that has reached us in written sources. The desire to obtain answers to the arising questions — who created, when, and for what purpose a particular monument of antiquity was built — has given rise to many legends among the people.

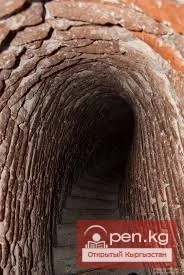

This also applies to the Burana settlement with the remnants of its enormous minaret. As early as 1860, M. I. Venyukov, traveling through the Central Asian outskirts of Russia, wrote that even at that time, the Kyrgyz (Kara-Kyrgyz) honored certain monuments of the peoples who had previously inhabited their lands. In particular, he briefly noted that the high "pillar" near Tokmak, supposedly made of raw brick, was especially revered by the Kyrgyz. According to legend, inside it died a certain khan's daughter, placed there by her father, who desperately tried to protect his child from a foretold demise from the bite of "fangs or other insects."

Later, based on the words of the Kyrgyz and Russian old-timers settled in Tokmak, several authors recorded the content of this legend in various versions. According to one of them, in ancient times (without specifying the time), a local khan was foretold that his beloved daughter would perish upon reaching the bloom of girlhood from the bite of the black poisonous spider, the karakurt (Lethrodoctes tredacimguttatus), which was found in large numbers in the Tokmak area. To create an environment for his daughter that would exclude the possibility of the prophecy being fulfilled, the father ordered the construction of a tower for her from burnt bricks, in which she spent her days and nights without escape in the uppermost room. As a precaution, from the very entrance to the minaret to the top of the internal staircase, servants were stationed, passing everything necessary to the khan's daughter after thorough checks. But the inevitable could not be avoided by any measures. At the foretold time, the girl was struck by two minor deadly stings from the poisonous jaws of the karakurt, accidentally brought in a basket with bunches of black grapes. In other versions, the tower was built by the khan for his only surviving heir — his beloved younger son. However, he too perished (following his older brothers) from the bite of the karakurt, which was carelessly brought into the upper room of the minaret by a negligent maid on a large plate of fruits.

Similar plots are widespread in Persia, the Caucasus, and westward — up to the shores of the Sea of Marmara (for example, in the legend of the Mandra castle near the Bosporus), while in Central Asia, such legends are associated with several archaeological monuments located in hard-to-reach mountainous areas.

Historically (in terms of reflecting in the Kyrgyz legend the time of the construction of the Burana minaret), the mention of the builder of the tower named Arslan-khan is of some interest. This was noted by V. V. Barthold in the last century as a typical nickname for some rulers from the Karakhanid dynasty. At that time, the Russian consul in Kashgar, N. F. Petrovsky, pointed out that in this case, we are unlikely to have an accurate echo of a past event, since among the Kyrgyz and Kazakhs, the names Kyzyl-Arslan-khan and Sattuk Bogra-khan are so popular that they are attributed with the construction of several buildings in various parts of northern Central Asia and Kashgar.

The earliest dated mention of the ruins of medieval cities in the valley of the Chu River or Chui still seems to be the information from "Tarikh-i Rashidi," relating to the 16th century. The information about the ruins of the city of Monora belongs to the author of this work — Muhammad Haydar Mirza Guragani, who saw the ruins of this monument of antiquity. V. V. Velyaminov-Zernov noted the information he provided on this matter in the middle of the last century. In a note to the second volume of his major work "Research on the Kasimov Kings and Princes," he provided texts from "Tarikh-i Rashidi" in Persian and Chagatai.

The first was given from a manuscript of St. Petersburg University, written with errors in 1843. The text in the Chagatai language is based on an incomplete manuscript adaptation of Muhammad Haydar Guragani's work in the Kashgar dialect, made by Muhammad Sadik Kashgari in the 18th century. In addition, the academician provided a Russian translation of the information about the Burana settlement. Later, in 1897, V. V. Barthold provided a Russian translation of the same passage from the Persian text, correcting minor inaccuracies made by V. V. Velyaminov-Zernov. There is an English edition: The Tarikh-i Rashidi of Mirza Muhammad Haidar, Duglat- A History of the Moghuls of Central Asia. —An English version, edited, with commentary, titles, and map by N. Elias, H. M. Consul-General for Khorasan and Sistan. The translation by E. Denison Ross. London, 1895.

The bibliographic rarity of the listed editions and the significant interest of the information contained in them about the Burana settlement, along with the small number of authentic manuscript copies, makes it worthwhile to provide the corresponding unique text about the archaeological object we are studying.