Hero of the Soviet Union Titov Andrey Alekseevich

Andrey Alekseevich Titov was born in 1905 in the village of Pokrovka, Przhevalsky district, in a peasant family of poor farmers.

He was Russian. A member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. He began his working life in 1918. He worked as a field worker, livestock keeper, and fisherman in the artel "Red Wave," in the Kirov collective farm, and in the district industrial combine of the Jety-Oguz district of the Issyk-Kul region.

He participated in the Great Patriotic War starting in October 1942. Guards private. Gunner of an anti-tank rifle. He received his combat baptism on the Stalingrad front. A brave warrior, he fought for three months at the walls of the hero city on the Volga. After the defeat of the Nazis on the Volga, he fought on the Oryol-Kursk direction.

For his courage and bravery displayed during the Great Patriotic War, A. A. Titov was awarded the Orders of the Patriotic War II degree, the Red Star, and medals. On January 15, 1944, he was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

In December 1944, due to health reasons, Andrey Alekseevich Titov was demobilized from the ranks of the Soviet Army and worked as the chairman of the Kirov collective farm in the Jety-Oguz district. He died in 1981.

TANK DESTROYER

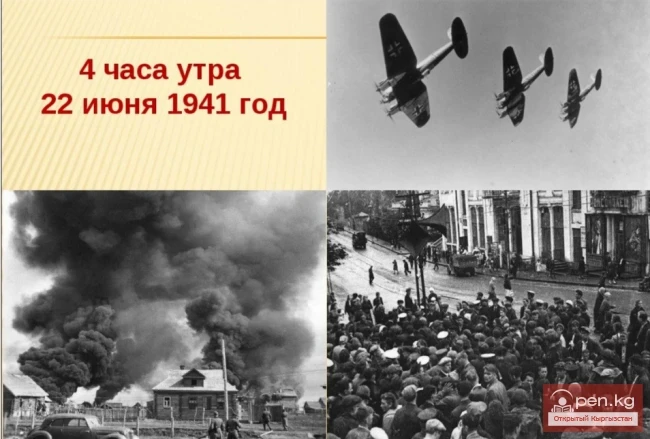

The news of the war caught Andrey Titov in the field. Together with his brigade comrades, he was clearing overgrown ditches and directing the cool, tight streams to the thirsty grain fields. The appearance of a boy courier rushing straight through the ripening field initially did not alarm anyone. Only the foreman grumbled harmlessly:

— He's trampling the grain, the little rascal!

However, soon the grain farmers heard:

— War-a-a!

It cannot be said that this news was completely unexpected. Talks about the possibility of Nazi Germany attacking the Soviet Union had been going on for a long time, yet the news was shocking. And within a few minutes, there was no one left in the field. Only a light breeze from the mountains gently swayed the resilient wheat stalks, and the larks, rising high above the sea of grain, continued their endless song.

When Titov reached the district military enlistment office, it was already crowded. Old men, who had fought in the First World War and the Civil War, were rolling cigarettes from harsh self-made tobacco, young guys stood apart, and sobs could be heard from the crowd of women. The doors of the enlistment office slammed shut, letting people in and out, and this sound resembled the explosions of distant shells. Finally, someone thought to remove the tight spring from the doors. Now only the steady noise of quiet conversations broke the silence.

Almost all of Andrey's peers received their summons on the first day, and he, confident that he would go to the front with them, entered the dimly lit corridor of the enlistment office. He could not know that he would periodically appear here for sixteen months and leave empty-handed. He understood that the Motherland needed not only fighters but also farmers, but this was a weak consolation. Titov seemed to physically feel the gazes of those whose sons and fathers had gone to the front on his back. And this made him open the doors of the enlistment office with their tight spring again and again. And finally, he managed to take his first military step. On October 25, 1942, Andrey Titov received his draft notice for the Red Army.

The days of preparation in the training regiment dragged on slowly. And although there was no time to be bored — all free time was taken up with military training, marches with full gear, political classes, and acquiring other necessary skills for a real soldier — the pages fell from the calendar as slowly as leaves from trees in a warm, prolonged autumn.

Meanwhile, events on the front unfolded rapidly. The enemy reached the Volga and stopped at the walls of Stalingrad.

The name of this city was on the lips of young warriors. Everyone wanted to be in the place of the defenders of the Volga stronghold, to be at the forefront of the battles. And they were lucky, these guys from the training regiment where Andrey Titov was located. With a group of reinforcements, they joined the cavalry division commanded by Colonel Belov, which was fighting at Stalingrad.

For three months, private Andrey Titov fought at the walls of the city and in the frozen steppes. Here he had his first encounter with the tank armada of the Nazis, which had triumphantly marched through the countries of Europe. In Russia, the fascist soldiers did not succeed in their parade. This was thwarted by guys like Andrey Titov. The anti-tank rifle, for which a fighter from Kyrgyzstan was appointed as the first number, was not the lightest type of firearm in both the literal and figurative sense of the word. But Titov was ready to endure any hardships and deprivations, to carry the multi-kilogram rifle on his shoulders to finally aim the sight at the most vulnerable part of the enemy tank's hull. Proportionally to the hardships endured, the military experience of the fighter grew. And during the battle on the Oryol-Kursk bulge, his account of destroyed enemy tanks was opened.

The front retreated westward. The retreating fascists were pursued by Titov's cavalry regiment. On September 16, Colonel Belov's cavalrymen reached the Desna. But it was still too early to think about watering the horses from this full-flowing river. From the well-fortified right bank, the fascists were firing at every inch of the left bank.

On the section of the front occupied by the division, it faced the 8th infantry division of the Hungarians. Forcing the water barrier on the move was quite difficult. So the cavalrymen began to prepare carefully for the crossing. They built rafts, set up pontoons, and sought makeshift floating means. On an early autumn morning, the water barrier was left behind, and the cavalrymen, pursuing the enemy, occupied the places of Mena, Voloskovtsy, and Feskovka. To assist their allies, the Nazis threw in elite units and managed to create a defense line at Dubrovo — Semychik — Stai.

They made every effort to prevent the breakthrough of Soviet troops in the Gomel direction.

On September 19, the fourth squadron of the 60th cavalry regiment, in which Andrey Titov served, fought its way into the village of Kobelyanka. While the enemy, fearing encirclement, regrouped its forces, the Soviet troops surged forward and, on the shoulders of the retreating enemy, occupied the settlements of Chertoreku, Tovtoles, and Kotovo, moving from the southwest towards Chernihiv. The operation, initiated by the strike of the 60th cavalry regiment, was so swift that in the battles for Chernihiv, the Nazis could no longer offer organized resistance. For this victory, the guards regiment was named the Chernihiv regiment. And Andrey Titov was awarded the medal "For Courage."

At the end of September, the regiment reached one of the main water barriers of the Great Patriotic War — the Dnieper. The cavalrymen concentrated in the forest west of the village of Novaya Runya. Each fighter knew that the time for one of the main tests had come. And how he prepared for it would determine not only his life but also the swift expulsion of the fascist hordes from his native land. The command allocated only two days for preparation for crossing the Dnieper. They could not give the enemy time to strengthen the defensive rampart; every hour allowed them to pull fresh troops and units to the main river of Ukraine.

Titov, for the umpteenth time, disassembled his anti-tank rifle, carefully wiping each part. The weapon was as familiar to him as his own five fingers. And it was no wonder, for it had been with him from Stalingrad to the Dnieper. Each scratch on the once blued barrel, on the once polished stock, reminded him of the days and kilometers of war. The sergeant had long suggested he swap his anti-tank rifle for a new one, but Titov refused:

— You don't change friends. You test their reliability in hard work. My anti-tank rifle has never let me down...

On the night before the crossing, none of the soldiers in the unit slept. The day ahead promised to be difficult, and every warrior understood this well. Some wrote letters home, some cleaned their weapons, while others, sitting near a veteran, listened to simple soldier tales. People tried to escape the thought of what awaited them in a few hours.

Those who had to fight know that there are moments at the front when volunteers step forward. By stepping out of line, a fighter signals that he is ready for any hardships, that he is physically and morally prepared for a feat, that he can be relied upon in the most difficult moment. An hour ago, tank destroyer Andrey Titov took such a step.

And now he was rereading letters from home, taking them out of a gas mask bag that had long lost its original purpose. Now it held letters, cartridges, and other simple soldier belongings.

From Kyrgyzstan, they wrote that things at the Kirov collective farm, where he worked, were going well, a good harvest was expected, but there would be difficulties with the harvest, as there was a shortage of mechanizers. And his mother also wrote that Andrey should hit the fascists harder and return home as soon as possible: the land longed for strong male hands...

The signal to begin the crossing sounded at dawn. Carefully pushing the rough but solidly built raft into the water, the soldiers of the assault group led by Lieutenant Simonov paddled to the middle of the river. Torn shreds of fog that had settled over the gray water not only hindered the enemy's visibility but also muffled the sound of the oars. The raft was spotted about seventy meters from the right bank. The targeted areas made the task easier for the enemy artillery. When there were about fifty steps left to the edge of the bank, a shell hit the raft, and the soldiers found themselves neck-deep in water. Raising their weapons above their heads, they struggled to get to the shore. Titov did not abandon his anti-tank rifle, although he had to drink plenty of cold Dnieper water.

Thus, the first part of the combat mission assigned by the command was accomplished. The bridgehead was secured. But now it needed to be defended until the main forces arrived. The element of surprise helped the volunteers to bombard the Nazis with grenades and seize the first line of their defense. Lieutenant Simonov ordered the soldiers to prepare for repelling a counterattack by the fascists. And it did not take long to arrive.

In the distance, the muted roar of engines could be heard. Tanks were coming. Titov strained to see into the space before the trenches, trying to guess from where they would appear to take a convenient position on the flank. The frontal armor of the armored vehicle does not fear either the bullets of the anti-tank rifle or even the shells of the anti-tank gun. Therefore, it was necessary to fire at the tanks from the flanks, getting as close to them as possible or allowing them to come as close as possible.

And right in front of the trenches, three "Tigers" appeared. Behind them came enemy machine gunners. Simonov ordered not to open fire without a command, and, approaching Titov, said:

— You are our god of war, our artillery. We are counting on you, Andrey. Try to stop those boxes, and we'll handle the infantry ourselves.

Minutes passed. The distance between the armored vehicles and the soldier, whose weapon seemed like a child's toy compared to the steel giants, was closing. An unequal duel began. Carefully aiming, Titov stopped the lead tank with his first shot. But the other two stubbornly continued to crawl forward. Choosing the moment when the second "Tiger" turned sideways to him, Andrey fired directly at the cross painted on its dirty green armor. The anti-tank rifle's shell hit the ammunition storage area, and a powerful explosion tore the steel giant apart. The commander of the third tank did not want to tempt fate and turned back, leaving the infantry that accompanied him. Most of the enemy machine gunners were destroyed, and the rest fled. That night, the remaining soldiers of the regiment landed on the bridgehead held by Simonov's volunteers, and in the night battle, the Vele farm was captured. In this battle, Titov personally destroyed three fascist machine gun nests and helped his comrades advance with minimal losses.

The squadron advanced westward relatively quickly, suppressing the resistance of small groups of the enemy in villages and farms. But near the village of Galki, the fascists regrouped and attempted to stop the cavalry's advance. Supported by tanks and self-propelled guns, the Nazis launched a counterattack. The cavalrymen had to dismount and dig in. Right towards the hastily dug trench where Titov was with his partner, a "Ferdinand" self-propelled gun was moving. Pouring lead into the space in front of it, the multi-ton giant did not allow the cavalrymen to raise their heads. Bullets cut the grass and raised fountains of dust. Carefully aiming, Andrey fired once, twice, three times. And the self-propelled gun burst into flames.

Figures in black overalls left the burning vehicle and tried to hide in the thick smoke. However, Titov caught up with them with machine gun fire.

Pursuing the retreating enemy, the squadron got separated from its units. The threat of encirclement arose. But the fighters did not want to retreat, to give the enemy the blood-soaked kilometers of their land; they simply had no right to do so. They decided to hold out until the main forces of the regiment arrived. This was, as Andrey Alekseevich Titov would later recall, one of his most difficult battles. Nine tanks and about a battalion of infantry were thrown against the group of brave cavalrymen. Titov set fire to two vehicles with his anti-tank rifle, and when he ran out of ammunition, he replaced the second number of the machine gun crew.

The hastily chosen position did not allow for a wide field of fire. The enemy soldiers quickly realized this and began to outflank the firing point. Then private Titov became... a living turret for the machine gun.

By propping his back under its tripod, he allowed the gunner to fire almost 360 degrees.

Thus, the fighters battled, replacing each other, until their units arrived. Then the enemy was pushed back, caught in a vise, and thoroughly defeated. For the battle near the village of Galki, private Titov was nominated for the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. This happened on October 6, 1943.

The battles for Soviet Belarus were heavy and bloody. Every inch of land, every settlement was paid for with great losses. Many comrades with whom Titov began his service laid down their lives for the liberation of the Motherland. Titov was seriously wounded as well. The joyful news of the awarding of the title of Hero of the Soviet Union to Andrey Titov by the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR found the tank destroyer in the hospital. The doctors did everything possible not only to save the Hero's life but also to return him to service. However, the medical commission of the hospital came to a unanimous conclusion: "Unfit for military service."

— Don't be discouraged, soldier, — said the attending physician at parting. — Victory is forged not only on the front lines.

And Andrey Alekseevich Titov returned to Kyrgyzstan, to his native Prissykul, exchanging military labor for agricultural work.

The door in the district enlistment office slammed shut behind the demobilized soldier who had been wounded. How many people had passed through it to go to the front. Not all of them opened it again, returning from the fronts of the Great Patriotic War. And those who came home had to work on construction sites, fields, farms, factories, and mills, both for themselves and for their comrades who had given their lives for the great right to live, work, and know what happiness is.

Hero of the Soviet Union Andrey Alekseevich Titov worked in the Kirov collective farm in the Jety-Oguz district of the Issyk-Kul region until his last days. A holder of many combat awards, he also received distinctions for his labor achievements.

Y. OMELYANENKO