The World Through Play. Category of Fact

Report

The report (as the main defining genre characteristic of "Autoparade"), becoming the primary method of organizing facts of reality, emphasized the film's closeness to "live" broadcasts, lending it the credibility of documentary broadcasting.

Uncommented Report

This is primarily a "broadcast of what is happening" in episodes at the mobile shop, a film screening organized for children in one of the yurts, the delivery of books and others to the shepherds. The absence of narration in these episodes draws attention to the event itself, to what and how its participants speak, allowing for observation of what is happening, from which the viewer draws conclusions independently.

Synchronous and asynchronous recordings of speeches, remarks, and sounds create a convincing, real atmosphere of the event.

Thus, the uncommented report contributes to the active "participation" of the viewer in the event: their empathy, reflection, which is so necessary for perceiving programs of the publicistic subsystem of TV.

The commented display of events, coming from the first person, serves not only for explanation but also for expressing a subjective point of view on what is happening in the episodes "visiting the old shepherd," "at the doctor's appointment," and others.

At the same time, it is both the author's assessment of the event and a peculiar characterization of the author themselves.

Interviews Taken Outside the Studio.

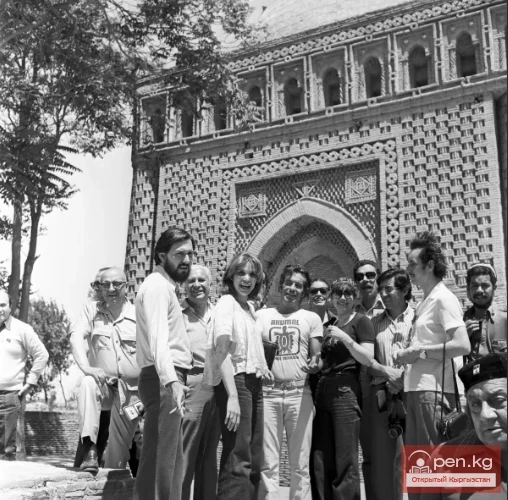

"Live" interviews are conducted by the authors only with the shepherds and their family members. Participants of the autoparade: doctors, writers, artists, service workers interest the authors only in connection with those for whom this journey is undertaken. The authors' questions are specific and friendly. The answers are sincere and candid.

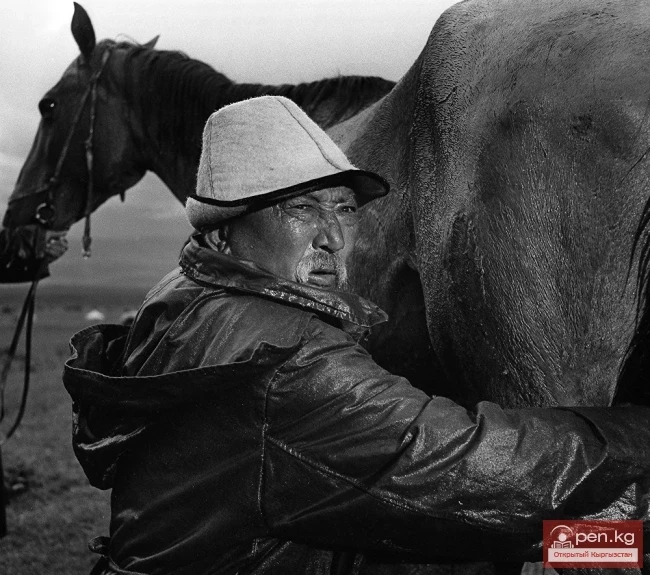

The camera is unhurried and attentive. Everything is done to ensure that the characters and thoughts of people who have lived for years in the snowy highlands are as close to the viewer as possible. Not always providing biographical data of the interlocutors, shooting interview episodes in close-ups and wide shots, mostly in natural settings, the authors strive to create a generalized portrait of the modern shepherd, highlighting the difficult conditions in which these people live and work.

Report with a Staged Situation. In this case, it is a report-staging, reconstructing the event — an "emergency" with a mobile power station that falls through the ice. "Restoration of the fact," born from documentary cinema, is an expressive means that requires skillful and careful handling.

"Excesses" here negate the efforts of documentary filmmakers who unreasonably use "theatrical playing techniques." It is no secret that the overwhelming majority of so-called "film reports" are sometimes shot in several takes, and their participants act as non-professional actors. Watching all this after "live" TV reports from the scene is very difficult.

In the context of the event report, inherent to the telefilm and carefully protected by television specificity, the report-staging and report-play destroy the authenticity of what is happening. Insincerity on the screen costs more: the conditions of perceiving the TV program, different from the atmosphere of a film screening, make themselves known...

Poorly executed in "Autoparade," reports with staged situations have, in my opinion, created a significant gap in the framework of the television document being constructed.

Visual.

The authors strive to bring the form of the film as close as possible to the form of a television broadcast — a method mastered by TV back in the mid-60s.

"The telefilm is more perfect in form the closer it is to a live television spectacle," wrote one of the leading Soviet documentary filmmakers, Igor Belyaev, at that time. And in his subsequent works from the late 60s, he "also vigorously tried to preserve the signs of 'televisionity.' "Operator Oleg Nasvetnikov would switch the turret with lenses, and I did not cut out these switches later. I asserted 'active carelessness' of the report as one of the signs of an unconditional film." "Active carelessness," with which work in tele-cinema once began, is present in almost all report episodes in "Autoparade": the frame is artificially disorganized, its composition is deliberately unthought-out, random, and the in-frame editing is unexpected. The "effect of presence" helped create the "effect of authenticity" of events.

Editing.

Some sparseness of the visual solution (especially noticeable when demonstrating "Autoparade" on the cinema screen): deliberately unhurried "zooms" and "pull-backs" from wide shots to medium shots and vice versa, long panoramas of mountains and roads, have determined the slowed-down editing solution. The length of individual shots: lines of cars climbing higher into the mountains, posters and slogans on them, landscape sketches achieve smoothness in editing. The conditions of perceiving the TV program logically dictated here the choice of means of visual-editing organization of the filmed material.

Visual-Editing.

They were determined by the conditioned structure of the documentary telefilm, the personification of audio-visual information about events related to the journey to winter pastures.

In the cabin of a specially equipped "rafic" for a difficult and long route, still on the way to the shepherd's camps, one of the film's authors — Jolon Mamytov — is introduced to us. With a microphone in hand, looking directly at the camera, he begins this journey for each viewer. For the first time in Kyrgyz tele-cinema, the "journalist" became a "visible person," not "a voice from the sky," reading an empty-sounding narration written by someone. The personification of information, trust, and the "conversational" intonation of the "live" author, their own assessment of what is happening perform the main function of publicistic communication: a 15-minute intervention in life. And we are already waiting for the answers to the questions posed by the author together.

The first interview — with a young shepherd.

We learn that two years ago, 32 people graduated from the local high school with him. Only two went on to become shepherds.

— It’s good that you came,— says the shepherd. — It’s hard when you don’t see people for a long time, but now that you’ve come — the mountains seem different...

The second interview — with schoolchildren.

Question: What do you want to become? (Among many professions — the most incredible... However, no, it’s all correct: here, at the edge of the world, at an altitude of four kilometers above sea level, they know everything — the influence of TV is evident...)

Question: And a shepherd?

Silence... — I don’t want to,— the boy smiles slyly,— it’s hard to be a shepherd!

For a mountain republic, whose main agricultural sector is sheep farming, this is already a problem. A significant and complex one. Armed with methods of screen publicism, it was raised by those who are able to notice unresolved issues in the diversity of life phenomena in time and draw public attention to them — journalists and television journalists. Thus, in the union of screen journalism and documentary cinema, "Autoparade" appeared — by its very nature and essence a telefilm.

Kyrgyz tele-cinema began the mastery of informational genres of publicism.

The First Works of "Kyrgyztelefilm." Essays on the Development of Television and Cinematography in Kyrgyzstan in the 70s—early 80s. Part-5