DOCUMENT OF OUR TIME

A documentary film is the conscience of cinema.

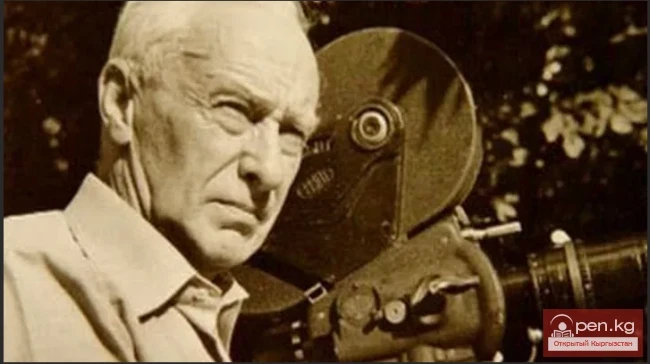

Joris Ivens.

In the autumn of 1972, at the Small Hall of the Funzen Cinema "Ala-Too" — "Chronicle," the film "Post" was screened, which won the Silver Dove award at the XV International Documentary and Short Film Festival in Leipzig.

Upon returning from Leipzig, Bekesh Abdildaev, the director of "Post," recounted:

— After the screening, colleagues from different countries approached me and asked about our hero, about his fate. They also inquired about Kyrgyzstan. Gerhard Schoymap from the GDR, By-Son from South Vietnam, Vasilev from Bulgaria, Lepit Harri from Finland, Natkane Nayonel from South Africa... And they also asked me: — Is the climate in Kyrgyzstan always so harsh? (We filmed in winter, in January, and we know what winter is like in Susamyr, in Tuya-Ashu...) — No, — I replied, — dear friends, Kyrgyzstan is beautiful, sunlit, and someday I will try to show you its other side, in different seasons and definitely in color...

Thousands of kilometers separate Leipzig from Kyrgyzstan, from the Susamyr Valley, where Kasymaly Tokoldoshev, the postman, lived and worked. He worked at the Kalinin District Communications Hub and lived in the village "March 8." The "area" of postman Tokoldoshev is the vast Susamyr Valley, its most inaccessible places and sections: Karakol, Chon-Balykty, Chaar-Tash. The herders, shepherds, and farm workers from the Sokuluk, Moscow, Kalinin, and Kemin districts are his good and loyal friends. For thirty years, postman Tokoldoshev delivered mail, packages, and money transfers. The Tokoldoshev family has 10 children, and Kasymaly-aka's wife, Zura, is a Mother-Heroine...

We learned about postman Tokoldoshev from an article in the newspaper "Soviet Kyrgyzstan." Soon, a cameraman filmed a segment about him for the newsreel "Soviet Kyrgyzstan." The entire country learned about the Kyrgyz postman from the newsreel "Daily News," and in the autumn of '72 — the residents and numerous guests of Leipzig, filmmakers from 45 countries around the world — everyone who watched "Post" by Bekesh Abdildaev and Valery Vilensky at the "Capitol."

...Across the full width of the screen, teletypes clatter, and intercity telephone systems hum. Telegram lines move like an endless ribbon. Trains rush by. Airplanes fly. They carry the mail. The prologue of the film is rhythmic and vivid. A peculiar "business card" of our days — "rush hour"... In an age of immense speed, those who quietly and unobtrusively work alongside people have become inconspicuous at first glance. But here — trains rush by, airplanes disappear from sight — and an elderly man, aged by his "quiet" work, carefully writes familiar symbols on stacks of newspapers, sorting just-received letters. Hopes, anxieties, joys, and sorrows, the labor of many unknown people now depend on him, the rural postman Kasymaly Tokoldoshev.

In an age of immense speed, are those who quietly work alongside people unnoticed? "Post" is a poetic proof: a person will help in difficult times, and only a person can understand happy moments. And no super technology can replace the warmth of the old Kasymaly's hands, his smile, his song. And then it becomes bright and warm in the remote winter dwelling. A person needs a person — and along the icy mountain path rides a horseman with heavy kurdzunas... Kasymaly carries himself confidently and modestly before the camera. The camera of Valery Vilensky captures the unhurried, attentive details of rural life, the solemnly austere graphics of ice-covered mountain paths, the fantastic clusters of icicles along the river — the bushes of willow, sheltered from thirty-degree frost under a reliable armor of ice, the smooth-dark, swift horses. In the film's unique visual tone, in the restraint of the editing, in the emphasized sparseness of the musical solution — a rhythmically flowing male vocalization, in the compositional completeness of the poetic narrative about the rural postman Tokoldoshev — lies the secret of the charm of "Post."

...Once, Chris Marker, a talented documentarian, bitterly acknowledged that documentary cinema is increasingly struggling to fulfill its functions in an age of widespread mass media. Only sensational documentary films, he said, would be able to exist on screen...

...The beauty of the winter expanses, the snow-covered spaces of Susamyr, is harsh. Only not every vehicle can navigate these paths.

And, leaving behind the latest mountain "loop" of driver Afanasy Kuzmenko, who has been working with him in Susamyr for several years, and the "horsepower" of the latest model refusing to serve in the frosty highlands, Kasymaly saddles his trusty transport — a single given force, bids farewell to Afanasy, and sets off. The journalists' favorite phrase "the road to people" takes on a literal meaning.

A sensation? The everyday life of rural postman Kasymaly Tokoldoshev.

In the distant thirties and forties, the pioneer of documentary cinema Dziga Vertov dreamed of innovative films — essays, film portraits of his contemporaries. "I would like to make a series of small films about living people of our time..." Now we know how difficult it was for Vertov on this path of visual understanding of the world — much was new then... "...At that time, he was told that films about specific people were generally the prerogative of feature films.

This was not said to dismiss Vertov or to shake off his claims. Those who spoke sincerely believed they were right."...

The development of Soviet cinema journalism went through various periods. But the dialectics of life, breaking dogmatic attitudes, restored respect for the document, trust in facts, life details, and specifics.

Changes in the country's social life also changed documentary cinema. "From general plans, documentary cinema moved to details, to specifics. From illustrative, organized according to a certain idea frame — to a frame capturing life in all its manifestations. From events and records — to the people making those records, and then simply to people — real people, not products of myth-making. From neutral, descriptive representations of reality — to a personal view of the world, to lyrical, authorial cinema. Finally, from the unembellished captured fact — to its philosophy."

The significant peculiarity of the revival of Soviet cinema journalism in the early 60s was that this process was observed simultaneously at different studios across the country — in the Baltics and in Moscow, in Leningrad and Moldova, while Kyrgyz documentary cinema made a leap forward. The works of I. Gershtein, B. Galanter, I. Morgachev, A. Vidugiris, B. Shamsiev became a revelation for the cinematic community.

The principles of organizing chronicle material and forms of artistic mastery of reality in Kyrgyz documentary cinema of recent decades are interesting for their diverse searches for harmonious paths of their merging. "Extracting" factual, documentary material from objective reality using "hidden" and "familiar" cameras, capturing life "unawares" and through prolonged observation, "restoring" past events, and sometimes, if the creative task requires it — resorting to direct staging (which, however, is still filmed using documentary cinema means), using synchronous and asynchronous sound recording, documentarians organize life facts in all their manifestations. In the genres of cinema storytelling: "Chaban" (director B. Shamsiev), "Cape of the Chestnut Horse" (director I. Gershtein), "Bridges of Duyshen" (director G. Degaltsev), "Post" and "Daughter of the Earth" (director B. Abdildaev), "Space" (director N. Borbiev); film poems: "Manaschi" (director B. Shampatiev), "Akyn" (director M. Ubukeev), "Beshik" — "Cradle" (director K. Kydyraliev); reports — "Hippocratic Oath" (I. Gorelik), "Report Not Finished" (M. Sherman and K. Orozaliev), "Addressed to the Sun" (A. Vidugiris and I. Morgachev), which actually marked the beginning of Kyrgyz cinema journalism.

...Through the loosely drawn curtains on the large, wall-sized windows, the winter darkness of a frosty Moscow evening peeks into the cozy conference hall. On the central wall, there is a relief of Lenin. On the side stands — draperies, softly illuminated from behind — familiar faces: Vertov, Shub, Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Vasilievs, Dovzhenko, Pyriev, Romm — photographs on a blue wall...

Today, several more portraits have been added to these in the Blue Hall of the Central House of Cinema in Moscow — time is relentless. Today, from the blue wall, Roman Carmen looks out, slightly squinting... And then, on a January evening in '73, Roman Lazarovich opened an evening of Kyrgyz documentary cinema here...

He made us — contemporaries, our descendants — witnesses of events that fell to the lot of one generation: the launch of Volkhovstroy, the construction of the DneproGES, the thirty-thousand-kilometer run of the first Soviet cars across Karakum to Pamir, the work of the expedition to save "Sedov"... Fights in Spain, the battle near Moscow, the resilience and courage of besieged Leningrad, battles in Stalingrad, the storming of Berlin, the signing of the capitulation by Nazi Germany, the Vietnam War, the victorious Cuban revolution — hundreds of thousands of meters of film that passed through the camera of operator Roman Carmen... Meetings with Tsiolkovsky and Hemingway, Papanin and Joris Ivens, Herbert Wells and Mikhail Koltsov, Mate Zalka and Ho Chi Minh...

World-renowned documentary filmmaker Carmen, summarizing the meeting initiated by the All-Union Commission of Documentary Cinema of the Union of Cinematographers of the USSR, said:

— We always eagerly await works from Kyrgyzstan, watching with interest. We are pleased that colleagues from Frunze have remained true to their best traditions, continuing the relay of deep searches for humanity — that which constitutes the uniqueness of Kyrgyz documentary cinema. And, it seems, it is natural that "Naryn Diary" — a significant phenomenon in documentary cinema — has once again come from Kyrgyzstan..."

And then, as he was leaving, Carmen said: "Let's meet more often"...

A decade in art is significant. Especially in documentary cinema, chronicles. Now, years after that memorable meeting, with the certainty that temporal distance provides — events, films, successes and failures, changes of names and surnames, one can probably say: the seventies were years of victories not by chance.

The regularity of the emergence of "Naryn Diary," "Post," "Bridges of Duyshen" was conditioned, motivated by their authors' attitude toward life material — not always sensational, but certainly — philosophically vivid, profound, real. An excavator operator, a rural postman, a ferry operator from a high-altitude river...

Real people, modest, simple. Not at all those who strive to get into the rays of "Jupiters." Rather — the opposite...

Undoubtedly — talent and the artist's intuition, life experience were needed to choose the hero of the long-awaited film in this way. Although "Diary," "Post," and "Bridges" were made by generally young people: Vidugiris and Ryshkov, Abdildaev and Vilensky, Dzhusubaliev, Degaltsev and Orozaliev, Makekadyrov, Sokolov.

And the study of character. This was on the agenda for documentarians then, fortunately, not only in words, not only on paper. This, remaining on film, still evokes the same feelings as in the early 70s...

Shall we give the floor to the authors of "Bridges"?

Geral'd Degaltsev:

— I have always been attracted to dramatic situations and the characters of people in them. Duyshen has seen a lot in his lifetime — both good and bad. He fought in the Great Patriotic War. Worked on a collective farm... Then he became a ferry operator — transporting people and vehicles from one bank of Naryn to the other. Day and night, winter and summer. Without vacations, without days off. He was needed, and he was genuinely, truly happy.

Konstantin Orozaliev:

— "Bridges" were filmed under difficult conditions. It was high and cold, and we had to manage to endure the frost for as long as possible: the camera, brought into warmth, instantly fogged up. And yet, it was easy to work. The very atmosphere around the old ferry operator, his work created such life situations, dictated such behavior of people...

You just have to see it in time, not miss it. The "hidden" camera psychologically helped to endear drivers, builders, collective farmers — different in age, character... We wanted the viewer to see Duyshen as he really was...

The Polish film critic called "Bridges" "a modest yet at the same time elevated story about an old ferry operator" when on June 10, 1973, in Krakow, the chairman of the jury of the X International Short Film Festival, artistic director of the "Frame" association Jerzy Kawalewicz presented G. Degaltsev with the "Golden Dragon" — a special award from the Chairman of the Presidium of the People's Council of the city. "If I were a jury member, I would have given Degaltsev the Grand Prix," wrote the Krakow "Festival Newspaper" after the competitive screening of the film. "This is a touching and very humane document of our time" ...

But — let’s return once more to Moscow in '73, on a winter January evening, when, after the screening at the Central House of Cinema, there was a discussion of the films brought from Frunze. The opinions of colleagues were mixed...

Film critic Lev Roshal, noting the valuable quality of Kyrgyz documentary cinema — the desire to choose interesting life material, the increased ability to observe characteristic details, admitted, at the same time, that the absence of "topical" works in the shown program, films addressing significant problems, is unfortunately observed not only at the studio in Frunze. Muscovites compared what they saw with some works of Kyrgyz filmmakers from the late 60s. And what then?

— I cannot help but mention what worries me... — (Yuri Avetikov, chief editor of the Central Studio of Documentary Films). — A few years ago, you made a film about an old man who grew a garden on arid land.

A good film... But after watching the current films — "Bridges of Duyshen," "Post" — it is clearly noticeable: both they and that film — "Garden," were made, in general, according to one principle, they are similar. The heroes of all three are old men, and there is something of parables in these works... They are rather narrative novellas with real people "in the lead role"... This conventionality, it seems to me, involuntarily constrains you, limits the possibility of penetrating into the depth of character...

— In your films, I saw the national character, — said director of the Central Studio of Documentary Films Gemma Firsova. — Unlike other studios, your films are similar in a good way... We, Moscow documentarians, can envy you...

- What do I value in Kyrgyz documentary cinema? (director of the Central Studio of Documentary Films Ekaterina Derbysheva). — First of all, the conciseness of the cinematic narratives — small in volume stories about specific, interesting people that you enthusiastically tell. Secondly, the simplicity of the works, the absence of false significance, pretentiousness, that high simplicity, which is a sign of the artist's maturity. In the films we just saw, this high simplicity achieves great strength. I just met an interesting person, a postman. Together with him, I traveled his daily route in the mountains, saw his face, saw how cautiously the horse stepped on the edge of the ice... This, in my opinion, is dramaturgy — restrained, not verbose...

And, although in some assessments, as you noted, familiar tones of opponents of films about "living people," portrait films, the judgments of documentarians accurately, albeit somewhat sketchily (which was quite natural), outlined the situation that had developed in the first half of the 70s in the documentary cinema of the republic.

Descriptiveness, stating, illustration were leaving the documentary screen. In their place came reflection, analysis. And in an age of widespread television, only "informational" in our eyes was no longer a noticeable merit even of film periodicals. Already in the mid-70s, the works of journalists from "Kyrgyzfilm" clearly announced a new approach to mastering life material. An interesting event became not only and not so much a reason for information but a starting point, an initial impulse for a more detailed story about people and their specific deeds. About a person who often remained alone, unfortunately, and sometimes still remains "off-screen" in momentary production information... But a natural question arose: how does a special issue of a newsreel (pre-planned, ingeniously filmed and edited) about an interesting collective or one person differ from an essay? For which more time is allocated — which is fundamentally important when it comes to cinematic observation and more resources? Especially since the viewer, practically always, without theoretical calculations and economic estimates sees "further and deeper"... A solution was found — reasonable and timely. Since January 1974, the newsreel "Soviet Kyrgyzstan" began to be released not three, but once a month, and due to the freed "parts," documentary films began to be made. This "production" moment may seem organizational at first glance. In fact, however, changes began in the development of documentary cinema in the republic, the consequences of which became evident in the increase in the number of documentary films, the expansion of their themes and geography. Initially quantitative, they gradually began to touch on the qualitative side of the matter.

The themes explored by documentarians in the 70s were undoubtedly interesting. The creation of images, studies of the characters of miners and hydro builders, the chairman of an international collective farm and employees of a high-altitude research station, workers of an electric lamp factory and a talented self-taught artist, girls who came from remote ails to the big city to study as weavers, and helicopter pilots known for their extraordinary courage... Of course, it is naive to wish to see each film as an "opening" of a theme, hero, problem. Average, "transitional" works have been, are, and probably will still be. Too many factors must come together for a work of high-class documentary cinema to emerge. And even excellent life material, alas, does not guarantee success. But can the thought of the "inevitability" of average films — that did not become the discovery of Man? A document of our time?

Kyrgyz documentary cinema of the 70s had many unresolved problems.

This includes excessive enthusiasm for reconstructing events — undoubtedly permissible in documentary cinema, but, of course, not the main, not the only way to tell about contemporaries.

This is also the "eternal" script question: authors "from the outside" were repelled by the "specificity" of cinema, professional filmmakers did not always see life, concrete problems in all their fullness and ambiguity.

This is also the almost complete absence of problem films, films addressing issues, the lack of frank, passionate, party journalism in the work of those who rightfully consider themselves students and followers of Dziga Vertov...

Problems, problems... Shamsiev, Okeev, Kydyraliev left for feature cinema, Vidugiris was gathering. In documentary cinema — unexpectedly for many — the voices of Abdildaev, Vilensky, Degaltsev, the Orozaliev brothers, Rakhmatulin began to sound confidently... New names appeared in documentary filmmaking — N. Borbiev, Abdykulov, Dzhergalbaev, Yusupzhanova, Akmataliev, Jadrin.

Kyrgyz documentary cinema was completing its fourth decade.

Kyrgyz Television and Cinema. Television and Cinematography of Kyrgyzstan in the 70s—early 80s. Part 6