ANNA AND ALEXANDRA

Sergey Kashevarov was from the merchant class of Kazan. His father owned a bakery where the whole family worked. Sergey married at twenty-eight after serving in both the White and Red Armies. Alexandra was four years younger than him. The daughter of a well-known doctor in Kazan, Iosif Bogdanov, she buried her first husband and retained his rare surname, Ksu-Erbo, which was uncommon for Russian ears.

In 1928, Sergey would arrive in Frunze, and Alexandra would come a year later after finishing her studies in Leningrad. He would become an accountant in the irrigation management, while she would teach German.

Every summer, the Kashevarovs would go on vacation to Kazan. Sergey’s sister Olga would come from Leningrad—she sang at the Kirov Theater, formerly the Mariinsky. Alexandra’s sister would arrive with her husband, geologist Yevgeny Rutkovsky, and their daughter Stasya. Sergey never left his niece, who looked very much like his wife, for a moment.

The last time the Kashevarovs went on vacation was when Stasya was seven.

The cheerful river tram would bring the Kashevarovs and Rutkovskys from Kazan to the old pier of Tashovka, where the family cow would joyfully greet them with a familiar moo. The dacha was two stories high and stood in a garden. The Volga was nearby. The garden was dark with cherries—large, Vladimir cherries—only from below, under the trees, a reddish light shone through: the leaves, no matter how hard they tried, could not hide the cool drops of wild strawberries from view.

In the evenings, they sang. Olga would start, followed by Sergey and Alexandra—the song floated over the Volga.

At that time, Uncle Sergey taught Stasya how to swim and gifted her a large orange-red ball.

At ten, after her mother’s death, Stasya stayed with her father, and at fourteen, after his arrest, she was alone.

A year later, in August of '41, she left very quickly, in just two weeks and even in a passenger car, dressed up in Frunze, leaving behind in Moscow, in a communal apartment room, all her belongings, her father's books, and the large orange-red ball.

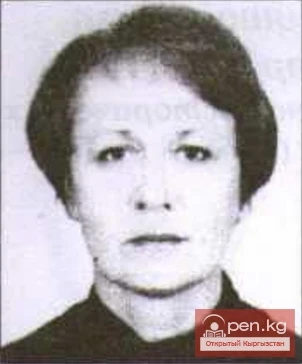

... I was helped to find Stanislava Yevgenevna Rutkovskaya at the Pedagogical Institute: they gave me her home phone number. :) In July of '39, Alexandra Iosifovna Ksu-Erbo-Kashevarova wrote about her: my sister is married to a certain Rutkovsky, they have a daughter, and my husband and I are childless and would like to adopt our niece...

This was an open, very personal letter. A sheet of paper, typed with one space between lines, on both sides, on a malfunctioning state typewriter: "As I have learned from a source in the Moldovan colony, my husband returned to the cell after interrogations as an abnormal person—on the brink of madness. I was given his note, from which it is clear that, according to him, he 'could not withstand the trials and stands at the shameful post'... I could not get an appointment with the new People's Commissar of the NKVD of the Kyrgyz SSR, but how can I trust those who were executors of the orders of Lotsmanov?"

The letter was titled a complaint. And it was addressed to the new People's Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR.

Comrade Beria did not respond to citizen Ksu-Erbo-Kashevarova.

With the stamps of incoming and outgoing NKVD of the USSR, it returned to Frunze and was filed in investigative case No. 1319. Just like the statement from Galina Pavlovna Lvova: I ask to review the case of my father, Lvov Pavel Konstantinovich, as I consider him completely innocent...

Galya Lvova was studying at the biological faculty of Moscow State University, living in a dormitory on Stromynka. In room No. 443, there were six girls who had come to study in Moscow.

Galya Lvova was finishing her second year. Stasya Rutkovskaya was in the fifth grade.

They walked the same streets, rode in the same subway cars, bought ice cream from the same vendors: Galya studied in central Moscow, on Mokhovaya, while Stasya lived on Sivtsev Vrazhka.

They did not know each other, were not acquainted, daughters and nieces of "enemies of the people." Today, only they preserve the memory of those who, by the will of fate, became hostages in the deadly games of great and small leaders with their own people—women of similar fates, of one, passing generation.

I told them about each other and invited them to the editorial office. The first to arrive was Galina Pavlovna. Then Stanislava Yevgenevna. They talked. About fathers, children, grandchildren, prices. They exchanged phone numbers. I saw how, holding hands, helping each other, they cautiously descended the not steep steps of the editorial entrance.

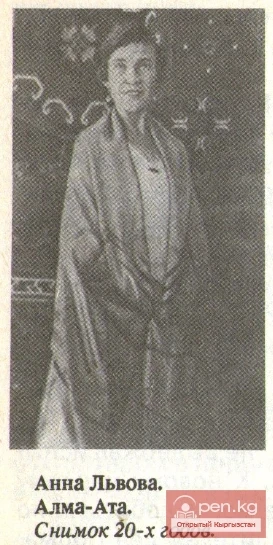

Time stopped. And then it went backward. On the table lay two photographs: Anna Lvova was younger than her daughter. Alexandra Ksu-Erbo-Kashevarova was younger than her niece.

Old photos, beautiful faces. "I was photographed in the summer, on happy days," Anna wrote on the back of the photograph. Alexandra in the portrait, taken by an unknown but undoubtedly real photographer, was seventeen.

Who knew what awaited them ahead?

On May 16, 1956, senior investigator of the KGB under the Council of Ministers of the Kyrgyz SSR, Captain of State Security Tatarinov, interrogated Anna Vasilyevna Lvova, a pensioner living in Frunze, as a witness.

On May 17, senior investigator of the prosecutor's office of the Voronezh region, Yuroda Bobrova Khudaybergenova, interrogated Alexandra Iosifovna Ksu-Erbo-Kashevarova, a teacher at Bityugskaya Secondary School No. 2 in the village of Korshevo, Bobrovsky district, as a witness.

Investigator Tatarinov had already received answers to his questions made during the verification of materials regarding the case of "officers of the old tsarist army Barudkin, Lvov, and Kashevarov, recruited into a counter-revolutionary espionage organization by the resident of the Anglo-Japanese intelligence Talizin, located in Western China."

There was no information about Talizin in the KGB archives: neither in Moscow, nor in Almaty, nor in Tashkent. There was none in their own archive in Frunze. There were no investigative cases of former officers of the White Army Talizin, Barudkin, and Lvov after their return from China in '21-'22.

The address bureau of several republics provided information about Talizins Alexander—Vasilyevich and Prokopyevich, natives of Leningrad and Chelyabinsk regions, born in 1900 and 1910. However, the "resident" Talizin was at least forty in the late twenties...

Information about Talizin, Barudkin, Lvov, and Kashevarov was not found in the Central State Special Archive of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR either. The verification was repeated multiple times: on the reverse side of the request form (for each separately)—several stamps, signatures, and dates. Information was provided by more than one department.

A negative response came from the Central State Archive of the Far East. The report from the Ministry of Internal Affairs for the Khabarovsk Territory stated: the data of these individuals do not appear in the records and documentary materials of the regional state archive.

In the Far East, Captain Tatarinov was not searching for traces of Frunze's "members of the 'Brotherhood of Russian Truth'" by chance.

According to the KGB of the USSR, obtained in Frunze in May of '56, the anti-Soviet organization "Brotherhood of Russian Truth" was established in China in 1926 and until 1930 was subordinate to the Supreme Circle of the BRP in Germany, and then it was reorganized into an independent Far Eastern autonomous department of the BRP.

The anti-Soviet activities of the BRP in China were financed and conducted under the guidance of Japanese intelligence.

In 1934, a diversionary-terrorist organization of the Harbin branch of the BRP was uncovered and liquidated in Moscow. The investigation materials indicated that the members of the BRP who arrived in the USSR were tasked with organizing diversionary cells in Moscow and other cities of the Soviet Union.

Whether there was a branch of the "Brotherhood of Russian Truth" in Central Asia was unknown to Lubyanka.

What stood behind this report?

What was hidden behind the combination of three words—brotherhood of Russian truth?

Loyalty to the officer's oath, desecrated to the Motherland and the executed tsar? The bitterness of defeat, demanding retribution? Unquenched patriotism? Nostalgia of the "White" emigration? The pain of Russians who lost Russia forever?

And also—can the information from Lubyanka from '56 be considered completely objective?

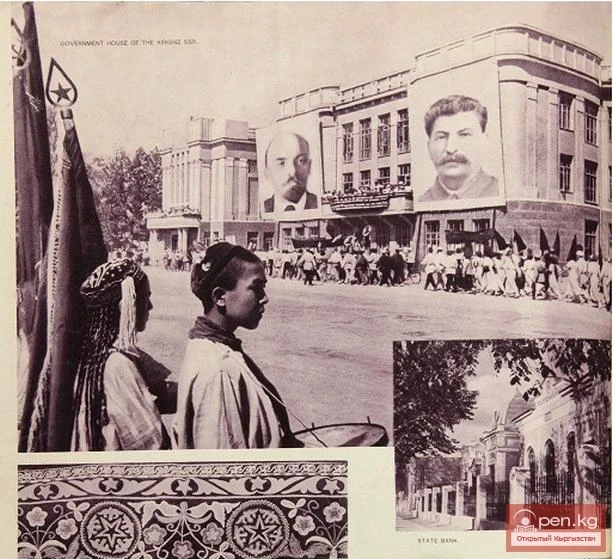

... It was the thirty-fourth year.

Order in the economy was still being "established" through repressions, the purge in the party had not yet ended. But in its higher echelons—the Politburo and the Central Committee—it was still possible to say what you thought. And the supporters of the policy of extraordinary measures were becoming fewer. In January '33, in a speech at the Plenary Session of the Central Committee, Stalin promised not to "spur" the country.

In July '34, the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs was established. The OGPU—now one of the subdivisions of the NKVD—began to lose its "glory" as the punishing sword of the revolution.

The brief "thaw" of '34 (how many of them were there in the history of the Soviet state?) ended on the first day of the first winter month. The "Law of December 1," prepared by Stalin just a few hours after Kirov's assassination (and not even formally approved by the session of the Central Executive Committee), removed the last brakes from the monstrous mechanism of repressions created by the Leader. The "Red Terror" was becoming mass.

Counter-revolutionary, underground, anti-Soviet, insurgent, espionage, terrorist, and diversionary organizations—everywhere, day and night, operationally and mercilessly—were uncovered and liquidated.

Was not one of them the "Moscow organization of the 'Brotherhood of Russian Truth'?"

But it is evident: neither in '38 nor in '56 were there any direct or indirect evidence of Barudkin, Lvov, and Kashevarov's affiliation with the "Brotherhood of Russian Truth."

Neither Anna nor Alexandra knew any of this.

In August, each was informed of the rehabilitation of her husband: Lvova in Frunze, Kashevarova in Bobrov.

They never learned that they had waited for their husbands in vain for the rest of their lives.

They did not know that they became widows eight months after the arrest of Pavel and Sergey, in November. Anna was forty, Alexandra thirty-eight.

The agency issued the truth in parts.

In '56, and for another three and a half decades afterward, the reason and date of the death of the rehabilitated and thus EXECUTED WITHOUT GUILT were not subject to disclosure.

Their burial place remains unknown even today.

Only on July 31, '91, at a meeting with the relatives of those whose remains were discovered in the Chon-Tash area, President Akayev announced a list of one hundred thirty-seven surnames, names, and patronymics.

The list was compiled alphabetically.

Between Kashevarov and Lvov were: Kenenbaev Kerim, Kyrgyzbaev Bakirdin, Kotlyarov Daniil Ivanovich, Krolitsky Ludwig Kazimirovich, Kuzmin Iosif Ivanovich, Kulnazarov Nurkul, Lepin Arthur Yanovich, Li-Kha Sami, Pitsenmaier Vladimir Augustovich, Luzanov Mikhail Nikolaevich, Lu-Chan-Toy, Liu-Zhe-Chin, Lyufing Yegor Emelyanovich, brothers Lyuft—Alexander Alexandrovich and Konstantin Alexandrovich...

Fifteen husbands, sons, fathers, on whom the vigilant gaze of the unyielding guardians of the revolution fell.

But first, there were other lists. In this one—from November 5, '38, Lvov Pavel Konstantinovich and Kashevarov Sergey Afanasyevich were side by side: No. 37 and No. 38. The alphabet was unnecessary. Above the list of forty-three surnames, it was printed in capital letters: the following individuals were shot.

At the top of the page, in a staggered format, with three spaces, also in capital letters, it was printed—act.

The foreign word with Latin roots had three meanings: deed, official document, part of a theatrical performance.

The deed was a crime.

The official document was an outrage.

The action did not take place on stage.

And the shots, and the cries—curses, farewells, and the black abyss of the pit on the slope of the hill, and the black silhouettes of nearby mountains, and the one-and-a-half-ton truck covered with tarpaulin, and the bodies that skilled hands of skilled people routinely threw into the black void—all were real.

And pain.

And blood.

And death.

And the moans that were heard for a long time, until dawn, from the depths of the earth.

And which no one heard.

Six girl students were preparing for the holiday on Stromynka, in Sokolniki.

Alexandra Ksu-Erbo, raised on classics, did not recognize the phonograph. But Stasya could listen for hours. In the sixth grade, on the eve of November 7, she and her father, for the first time since her mother's death, took a box of records out of the closet.

And the hostess Lvova started the favorite phonograph: both on the evening of the fifth, Saturday, and on the morning of the sixth, Sunday.

She played Utesov.

The needle had not been changed for a long time, the record crackled slightly:

...things are going well, and life is easy,

not a single sad surprise,

except for a trifle...

An excerpt from the book "The Mystery of Chon-Tash." published with the author's permission, Regina Khelimskaya.

The Mystery of Chon-Tash. The Case of Kashevarov and Lvov