TRAVELER ALEXEY FEDCHENKO IN TURKESTAN

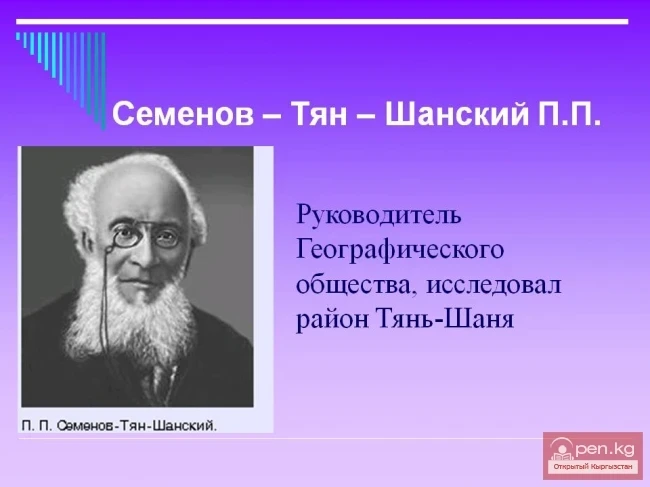

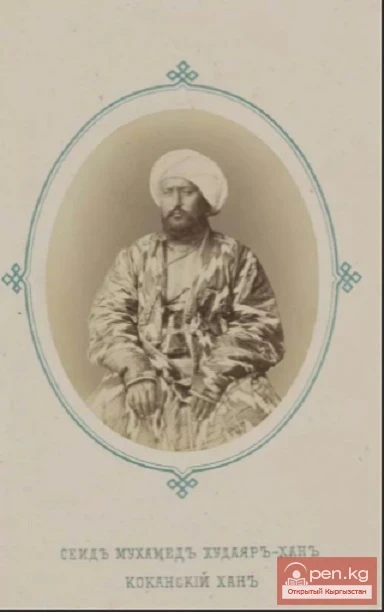

It is not surprising that the phenomenon of Kurmandzhan Datka caused genuine amazement among Russian and European travelers who visited Kokand, as even educated Western residents of the 19th century knew little about Turkestan. Having explored almost everything on the planet, from New Zealand to Tierra del Fuego, geographers of the past century primarily drew information about Central Asia from ancient Chinese chronicles, only occasionally daring to appear in the heart of the Eurasian continent. Only a few, like Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky or Pyotr Petrovich Semenov-Tyan-Shansky, ventured to do so.

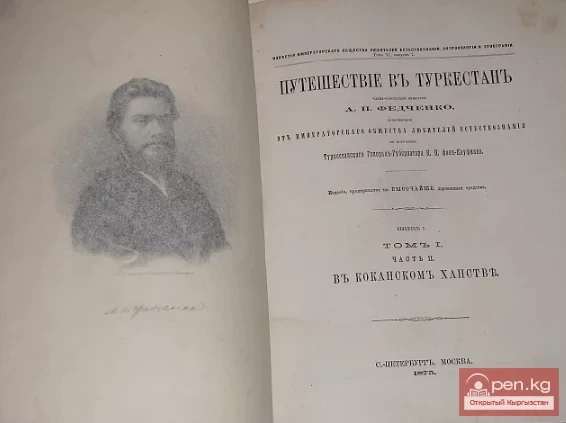

One of these brave souls was the Russian geographer, biologist, and traveler Alexey Pavlovich Fedchenko (1844 - 1873), who discovered the Zaalai Ridge and significantly enriched the scientific arsenal with knowledge about the mountains of the Tien Shan and Pamir. The son of an Irkutsk industrialist, who later became a bankrupt owner of a gold mine, he graduated with honors from the natural sciences department of the physics and mathematics faculty of Moscow University. He made a brilliant scientific career, becoming a candidate of natural sciences at the age of 24. He died at the age of 29 while attempting to climb Mont Blanc.

By that time, he was already known as one of the luminaries of Russian and world science. Bright pages in the scientist's biography include several expeditions he undertook to Turkestan between 1868 and 1871. The scientist collected quite detailed information about the flora, fauna of the region, its geographical features, and the customs of the peoples inhabiting this land.

Subsequently, a glacier located in present-day Kyrgyzstan was named after A. Fedchenko, discovered in 1878 by participants of the expedition led by V.F. Oshanin.

Aleksey Petrovich's faithful companion in almost all his travels was his wife Olga Alexandrovna Armfeldt - the daughter of a professor at Moscow University. She beautifully complemented her husband's research work by sketching the views of the mountain ranges that opened up to the travelers.

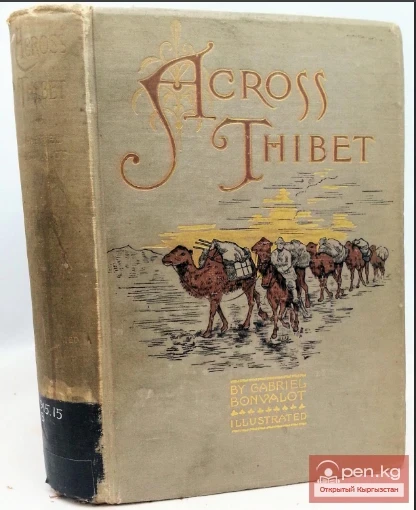

A. Fedchenko's Turkestan expeditions are worthy of a novelist's pen. Fortunately, the participant himself left detailed accounts of his travels. This book, "Journey to Turkestan," was subsequently published in 1875 in the "Proceedings of the Imperial Society of Natural Sciences, Anthropology, and Ethnography." Later, A.P. Fedchenko wrote in one of his letters: "Pamir and the country in the upper reaches of the Oxus (Amu Darya) cannot remain unexplored for long: either the Russians or the English will uncover its secrets... I, however, believe more (at least I would like to) that the Russians will do this and once again inscribe their name in the geographical chronicles, which, by common acknowledgment, already owes them so much."

During his Turkestan expeditions, the scientist traveled through the Kokand Khanate, descended into the Alai Valley, and left notes about the features of the Zaalai Ridge and its highest peak - named after Kaufman.

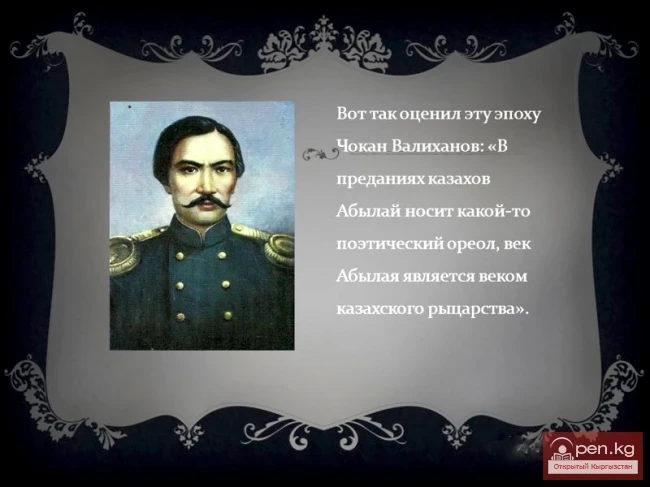

Among other things, the notes are interesting because they mention Kurmandzhan Datka. One important detail shows that the author, at least at the time of writing the notes, was quite poorly informed about the Alai queen: A. Fedchenko inaccurately conveys her name. But this makes the text all the more interesting for us as a documentary testimony from an external and impartial observer. Here is an excerpt: "...in the upper part of Alai, the power of the Kokandis must not be strong. The main authority there is considered to be the Kyrgyz woman Marmadjan-datka. She is a widow; her husband was the well-known Alim-datka, who played a significant role in the last internecine conflicts in the Kokand Khanate, notorious, among other things, for his brutal murder in Osh. He later perished; power passed into the hands of his wife, who independently rules the clan and enjoys great authority; our dzhigits spoke of her only with great respect. The khan himself holds her in high esteem and, in case of her arrival in Kokand, receives her as an important bek."

Here are several other episodes from his travels through the Fergana Valley. On June 15, 1886, the expedition participants received an open order with the khan's seal, obliging the subjects of the Kokand Khanate to provide assistance and hospitality to the travelers. Here is an excerpt from this document: "To the rulers, amins, serkers, and other officials of the Margilan, Andijan, Shaarikhana, Aravan, and Bulak-bashi districts and the cities: Osh, Uch-Kurgan, Chemians, Sokh, Isfara, Charku, and Vorukh, be it known this highest order: six Russian people, including one woman, with seven servants, are traveling to see the mountainous countries, therefore it is ordered that in each district and in every place they be received as guests, that none of the nomads and sarts disturb them, so that the aforementioned Russians may complete their journey joyfully and peacefully. This must be executed unconditionally!".

To accompany the expedition, the local authorities appointed eight dzhigits. The chief among them was Abdulkariyim karaul begi, a venerable old man about 70 years old. The others were mostly young men. A certain mirza Edgar also accompanied the travelers - their companion during their stay in Kokand. This companion was entrusted by A. Fedchenko to transport to the city of Margilan the belongings of the expedition members that were unnecessary for the upcoming trip to the mountains, and another useless load far from the comforts of civilization - a chest of silver coins.

After leaving Kokand, the travelers soon reached the snow-white peaks of the Tien Shan. Here is how A. Fedchenko describes the beauty of these mountains: "...I saw even more snow masses to the south. The farthest of them to the right were visible at an angle of 198 degrees; this was a whole group of peaks rising much higher than the snow line, sharply separating from the adjacent mountains. From them to the east, there was already a whole line of snow giants, still interrupted in places because they were blocked by nearby mountains. At an angle of 115 degrees, i.e., almost to the east, there was a peak that, despite its greatest distance, was still higher than the others. This summit was almost constantly covered by a cloud, and it took a long time to look at it to form an idea of its shape. The shape of this peak turned out to be very characteristic: a pyramid, the base of which is very large compared to its height; however, it is an irregular pyramid: its northern slope is steep, while the southern slope gradually transitions into the mass of mountains. Not a single black dot, all covered with snow! How I regretted that I had no angular measuring instrument; the distance was great, but it would still have been possible to determine how much this peak rises on the ridge.

Later, from below, from Alai, I saw this peak, and from there it seemed the highest. As for its height, due to the lack of measurements, I must be satisfied with indirect conclusions, which I will outline below when describing the Zaalai Ridge as seen from Alai."

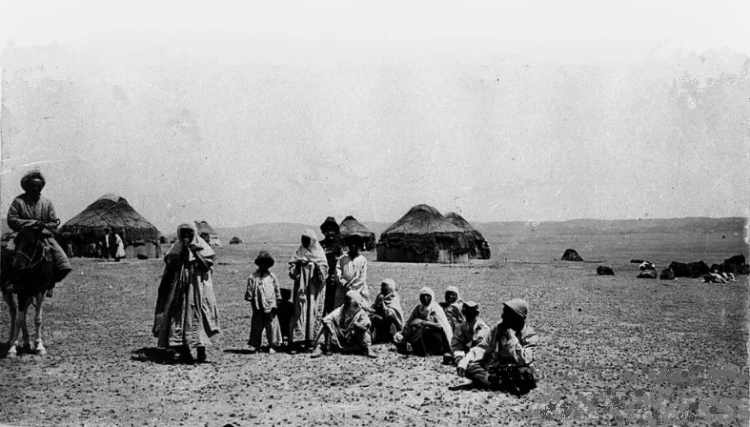

Let us also present some of the ethnographic information left by A. Fedchenko. In Alai, the scientist saw only two or three small burial mounds surrounded by a clay wall, with some buildings. As the author of the notes indicates, the building served as shelter for the local Kyrgyz who remained in Alai for the winter. "But such (buildings - Note by the author) are relatively few; most come to Alai only in summer from the Fergana Valley, and in winter they return and graze their herds on the vast uncultivated spaces, many of which are located close to the most populous settled settlements," adds the researcher. He continues, stating that the owner of the building was a certain Izmayil toksaba - the chief of the constantly nomadic Kyrgyz in Alai.

One of the burial mounds was a quadrilateral surrounded by clay walls up to 2 sazhen high, with only one gate on the northern side. Inside stood an old structure, completely encompassed by a new, much smaller one, and more like a small house. It served as a home for the owner of the building, with whom, it is said, his wives also live. Inside, sheds were attached to the outer wall of the burial mound, serving as protection in case of an attack. A spacious empty courtyard was intended for tying up horses. That was the entire simple structure of the fortress - insignificant, located in close proximity to the high mountains, from where one could throw stones into it. According to the author of the notes, under Izmayil toksaba, there were supposed to be 50-60 dzhigits - horsemen with rifles or sabers.

Let us interrupt the narrative with a small remark from the author of the notes, shedding light on some features of the local political situation at that time. It concerns the usual consequences of local internecine conflicts for the subjects of the Kokand Khanate, which shocked the Russian traveler. While traveling through the Fergana Valley, the researcher found many uncultivated fields. As he was explained, this was the result of deteriorating relations with Karategin - the area from which the peasants brought seeds for planting. As A. Fedchenko was told, it was precisely the dependence of agricultural lands on Karategin that was the main reason why the Kokandis so stubbornly suppressed the separatist aspirations of the inhabitants of this area to switch to Russian allegiance. The extremely negative attitude of the Kokandis toward the inhabitants of Karategin is illustrated by the following episode: "The toksaba received us, travelers, very kindly, repeating that the Karategin people are bandits. I poured out assurances of how I feel, etc.

I was amused by this comedy. Being inwardly furious at having to turn back from the foot of Pamir, I vented my anger by questioning the toksaba. How does he plan to deal with the Karategin people, at what time does he think the attack will be, does he have enough people, etc. It seems that it ended with the toksaba himself bursting into laughter; in general, he was a cheerful man, even indecently cheerful for a Muslim, which can be explained by the fact that he is Kyrgyz, and they have generally been little touched by the influence of Muslim etiquette. Our relations, despite my questioning about traveling further, despite the unsuccessful gift (a watch), were the most cordial."

The travelers settled for the night under a shed. At night, Alexey Fedchenko got up and took a little walk around the burial mound unnoticed by anyone. Only a little dog woke up and began to bark desperately. It barked for a long time, as a dog usually barks when it notices a stranger...

Here is another episode described by the author, enriching the collection of ethnographic information about the Kyrgyz: "I did not see the Alai Kyrgyz in their summer camps, except for the two small auls that met me in the Daraout gorge. The reason, as Nuru-Magomet biy explained to me, is that the Kyrgyz do not camp close to the burial mound, as the chiefs like to use them for work and generally turn to the nearest auls for various needs. According to reports, the summer camps in Alai are very rich in forage grasses, especially in the southern mountains, which the Kyrgyz particularly love because the grass does not dry out until autumn. I could not gather these grasses for the reasons explained above."

As Alexey Pavlovich laments in his notes, "my sincere desire, the aspiration to be in Pamir, dreams that I cherished since my departure in 1868 to Turkestan, did not lead to the desired result. I could only reach the northern outskirts and, most importantly, clarify the orography of the parts adjacent to Pamir from the north. My path, as I noted above, stopped at the foot of the majestic roof of the world - Bam-i-duneya, as the natives call this elevated land; the Zaalai Ridge that I saw constitutes the edge of this roof of the world. At times, I am seized with annoyance that our path ended at the toksaba's burial mound, that we could not step over this edge - the Zaalai Ridge, but recalling all the circumstances of the journey, I see that there could have been no other outcome."

This recognition turned out to be prophetic. As subsequent circumstances did not allow the scientist to continue his research in the Turkestan region. Here is what A.P. Fedchenko wrote about these circumstances: "How could we go for several days into a desert area without having supplies of either fodder or provisions! What we had with us was not enough even for the return journey from Alai: we went two days hungry."

In November 1871, the Fedchenko couple returned to Moscow, where they processed the collected collection and also gave numerous reports on their research in Turkestan. The results of the expedition were so significant that they attracted the attention of broad scientific and public circles. In May 1872, at the All-Russian Polytechnic Exhibition in Moscow, the Fedchenko couple successfully exhibited their section dedicated to Turkestan. That same autumn, Alexey and his wife went to France, and then to Leipzig, where they were offered to work in the university laboratory. The summer of 1873 was spent by the family with their newborn son in Heidelberg and Lucerne. There, to prepare for a new expedition to Pamir, A. Fedchenko decided to study the experience of mountain climbing in the Alps. For this purpose, on August 31, 1873, he arrived in the village of Chamonix, located at the foot of Mont Blanc.

The local naturalist Payot recommended that the traveler take two local guides with him. Unfortunately, they were inexperienced. However, during the ascent, when they were on the Col de Géant glacier, the weather suddenly worsened. According to the guides, Alexey Pavlovich felt unwell, and the guides, exhausted from helping him, decided to leave him and went down for help. When help arrived, Fedchenko was already dead. His wife, Olga Alexandrovna, who was investigating the circumstances of her husband's death, claimed that when help arrived, he was still alive, and if it had not been for the indifference of the local authorities, who did not send a doctor to the injured, Alexey Pavlovich could have been saved.

The traveler is buried in the cemetery of the village of Chamonix, not far from the place of his death. A granite stone with an inserted marble plaque is placed over his grave, which reads: "You sleep, but your works will not be forgotten." Thus ended the earthly journey of the remarkable Russian naturalist. The fruits of his research during the Turkestan expeditions were to have a long way to go to the hearts of readers, eventually entering the golden fund of scientific discoveries of Turkestan researchers.

And in the memory of Kyrgyzstanis, the remarkable Russian geographer remains as one of the first discoverers of the homeland of Kurmandzhan Datka for Russians, as well as, of course, for the inhabitants of the West.

Kurmandzhan Datka