The History of Modern Kyrgyz Science

Since ancient times, humans have pondered questions about the origins of everything, the emergence of life, the explanation of death, and so on. Answers to these and other questions were sought and found in everyday life.

Kyrgyz people, like other nations of the world, had their own body of knowledge about the laws of nature, celestial bodies, and the origins of the universe. Everyday experience taught them to treat various diseases in humans and animals. This knowledge, passed down from generation to generation, accumulated over centuries by "nameless scholars," primarily the people. The practical knowledge accumulated throughout the history of the Kyrgyz ethnos served as the foundation for modern scientific knowledge as we know it today. Of course, the level of modern science in Kyrgyzstan is directly related to the socio-economic and political processes of the Soviet era. It was this era that elevated Kyrgyz science to the current heights represented by a cohort of scholars, many of whom are documented in this book. What distinguishes science from empirical knowledge?

Certainly, the ancient inhabitants of Kyrgyzstan, who left drawings on the rocks of Saymaly-Tash and in other locations in the second millennium BC, did not ponder this question. Their drawings of animals, as well as simple solar symbols and others, were the first evidence of an attempt to reflect the spiritual state, faith, and description of the surrounding world of the ancient inhabitants of our region.

Not years, but entire millennia passed before the ancient Semirechye tribes invented their first writing system. Writing, as an attribute of the civilizational development of ancient nomads in Central Asia, dates back to the third century BC. Unfortunately, this writing, samples of which were found during the excavations of the Issyk-Kul mound near Almaty, has not yet been deciphered. It is known to historical science that the same tribes of the northern part of Semirechye inhabited the territory of Kyrgyzstan. They were the Saka-Tigrahauda, a conglomerate of proto-Turkic and Eastern Iranian nomadic tribes.

Another significant event in the history of the development of scientific knowledge was the emergence and spread of alphabetic systems in Central and Inner Asia. As is known, the ancient Semitic people—the Syrians, specifically those of them who, due to their affiliation with the Nestorian branch of Christianity, were forced to emigrate from the Middle East to the east—prompted the emergence of both Sogdian and Orkhon-Yenisei scripts in Central and Inner Asia in the 6th-7th centuries.

Of course, it should not be forgotten that the early medieval Turks included in their runic-like alphabet their own signs, which trace back to pre-alphabetic writings of the proto-Turks (for example, the sign i, T- "arrow" / "ok," which provided the letter sign for the consonant "k," or the sign - "moon"/ай, to denote the consonant "y," etc.).

The Kyrgyz variant of this writing also developed. The Kyrgyz, who restored their statehood on the Yenisei (6th-10th centuries AD), were involved in the development of a special variant of the Orkhon-Yenisei written culture. Representatives of the Yenisei Kyrgyz left a rich collection of epigraphic monuments in the Sayano-Altai region from the 7th to the 12th centuries. Thus, the Kyrgyz became an ethnos that used this writing for a longer period compared to neighboring Turkic peoples. One of the outstanding epigraphic legacies of the Kyrgyz is the Sudzhin monument, which was discovered in 1909 and published in 1913 by G.I. Ramstedt, and later reissued by S.E. Malov and the Turkish scholar H. Orkun.

Thus, the author of the Sudzhin-Davan inscription is a certain Kyrgyz hero and military leader named Boyla Kutlug Yargan, who also served as an officer under another Kyrgyz noble named Kutlug Baga Tarkan Uge. The historical value of this inscription lies in the fact that it is an author's testimony from a Kyrgyz nobleman and commander who faithfully fulfilled the combat task assigned to him on Orkhon land.

In the early Middle Ages, some representatives of Turkic and Kyrgyz nobility studied in China. There are records of a literate Kyrgyz nobleman who ordered a copy of a Buddhist manuscript for himself. An educated stratum was also needed for diplomatic missions. Chinese sources mention that at the beginning of the 8th century, a representative of the Kyrgyz ruler was in Tibet. This coincides with the epigraphic monuments of the Yenisei Kyrgyz, which contain information about a Kyrgyz envoy sent to Tibet from the Kyrgyz Khaganate on the Yenisei. The 10th-century Arab traveler Abu Dulaf described the Kyrgyz as a people with their own writing.

"And then we reached the tribe of the Kyrgyz... They have a temple for worship and a pen for writing... Their language is rhythmic, which they use during worship. Their banner is green... When they worship, they look to the south. For them, Saturn and Venus are considered sacred."

(From "The First Note" of traveler Abu Dulaf).

Indeed, on the territory of Kyrgyzstan, particularly in the valleys of Talas and Kochkor, Orkhon-Yenisei inscriptions have been found. By style, they are closer to the Yenisei (Kyrgyz) variant than to the Orkhon one. It should also be added that under the influence of the Nestorian Syrian colonies, the first Turkic-speaking Christians appeared in Kyrgyzstan, leaving their epitaph monuments. All these writings were the experience of the Kyrgyz in mastering and enriching the cultural achievements of various regions connected by the Great Silk Road.

The next stage in the development of scientific knowledge among the peoples of Kyrgyzstan is associated with the Muslim East. As early as the 9th century, the first mosques appeared in some cities of Kyrgyzstan. With the declaration of Islam as the state ideology of the Karakhanid Khaganate in 960, the territory of present-day Kyrgyzstan was fully integrated into that special world, which is conditionally referred to in science as the "Muslim Renaissance."

A significant contribution to this was made by representatives of the peoples of Central Asia. Among them were great figures: the philosopher al-Farabi, the mathematician al-Khwarizmi, the physician Ibn Sina, the mathematician and astronomer al-Biruni, the mathematician al-Fergani, and others.

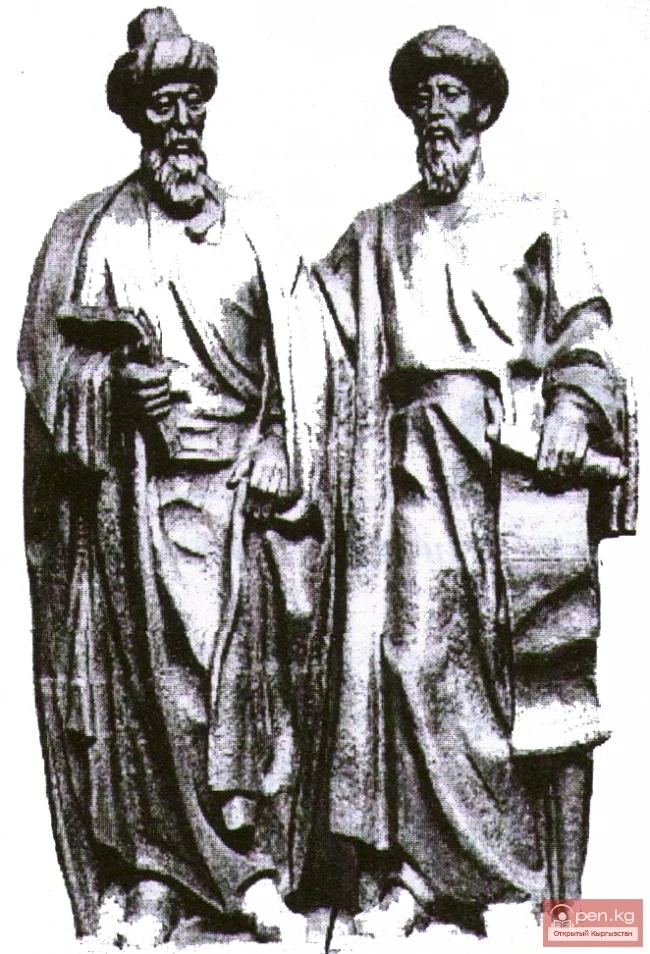

The ancestors of the Kyrgyz people—Yusuf al-Balasarghuni, a didactic poet and scholar from Balasaghun, a city near modern Tokmak, as well as Mahmud al-Kashgari (al-Baraskani), a native of a city on the shores of Issyk-Kul, were two bright stars in the sky of scientific thought during the Karakhanid period.

There were also other scholars who contributed to the development of Muslim scholarship. Among them, the Osh jurist (faqih) Omar ibn Musa al-Oshi (died in December 1125) and the Uzgen scholar Ali ibn Sulaiman ibn Dawud al-Khatibi al-Uzqandi were specifically mentioned in the book "Mu'jam al-Buldan" ("Alphabetical List of Country Names") by the Arab encyclopedist Abu Abdullah Shihab ad-Din ar-Rumi al-Hamawi, known by the nickname Yakut (1179—1229).

The periods of the Kara-Khitan rule (1130-1211), and especially the Naiman (Küchlüq Segizdik, 1211-1218) and Mongol domination in Tengri-Too (from 1218 until the abdication of the descendants of Genghis Khan at the end of the century) were not only times of ethnocultural synthesis and mutual influences but also an era of decline for scientific centers, which were part of the eastern periphery of the Muslim Renaissance.

Many madrasas were erased from the face of the earth, libraries were plundered or burned, and in the places of former cities, livestock often grazed.

Gradually, from the second half of the 13th century, thanks to local educated officials serving the Chagatai, the Golden Horde, the state of Haidu, and such local rulers as Sugnak-tegin, the governor of the Semirechye vilayet El-Alargu, the role of science increased.

Read also:

Zheenaly Sheriev

Sheriev Zheenaly (1932-2002), Candidate of Philological Sciences (1970), Professor (1991) Kyrgyz....

Tourist Area Management Program

The project "USAID Business Development Initiative" (BGI), within the tourism...

Numerals, Mood, Verb in the Kyrgyz Language

Numeral Names. Cardinal numerals can be simple (1 - bir, 2 - eki, 3 - üç, 4 - dört, 5 - bet, 6 -...

Atkurova Altynai Razbaevna

Attykurova Altynai Razbaevna Art historian. Born on November 23, 1973, in the village of Gulcha,...

Types of Higher Plants Listed in the "Red Book" of Kyrgyzstan (1985)

Species of higher plants removed from the "Red Book" of Kyrgyzstan (1985) Species of...

Prose Writer, Journalist Djapar Saatov

Prose writer, journalist Dzh. Saatov was born on February 15, 1930, in the village of Alchaluu,...

Prose Writer, Poet Junay Mavlyanov

Prose writer and poet J. Mavlyanov was born in the village of Renzhit (now the village of...

Prose Writer, Critic Dairbek Kazakbaev

Prose writer and critic D. Kazakbaev was born on June 20, 1940, in the village of Dzhan-Talap,...

The title translates to "Poet Soviet Urmambetov."

Poet S. Urmambetov was born on March 12, 1934, in the village of Toru-Aigyr, Issyk-Kul District,...

Zhorobekov Zholbors

Zhorobekov Zholbors (1948), Doctor of Political Sciences (1997) Kyrgyz. Born in the village of...

The Poet Kubanych Akaev

Poet K. Akaev was born on November 7, 1919—May 19, 1982, in the village of Kyzyl-Suu, Kemin...

Kenesariyev Tashmanbet

Kenesariyev Tashmanbet (1949), Doctor of Historical Sciences (1998), Professor (2000) Kyrgyz. Born...

Shukurov Dzhapar Shukurovich

Shukurov Japara Shukurovich (1906-1963), linguist, Turkologist, organizer of science in...

Poet Dzholdoshbay Abdykalikov

Poet J. Abdykalikov was born in the village of Tashtak in the Issyk-Kul district of the Issyk-Kul...

Poet, Critic, Literary Scholar Omor Sooronov

Poet, critic, literary scholar O. Sooronov was born in the village of Gologon in the Bazar-Kurgan...

Poet, Prose Writer Medetbek Seitaliev

Poet and prose writer M. Seitaliev was born in the village of Uch-Emchek in the Talas district of...

Types of Insects Listed in the 2004 IUCN RLTS Not Included in the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan

Insect species listed in the 2004 IUCN RLTS, not included in the Red Book of Kyrgyzstan 1....

Literary scholar, prose writer, poet Dzaki Tashtemirov

Literary scholar, prose writer, poet Dz. Tashtemirov was born on October 15, 1913—October 7, 1988,...

Poet, Art Historian Sarman Asanbekov

Poet and art critic S. Asanbekov was born in the village of Aral in the Talas region of Kyrgyzstan...

Chorotegin (Choroev) Tynchtykbek Kadyrmambetovich

Chorotegin (Choroев) Tynchtykbek Kadyrmambetovich (1959), Doctor of Historical Sciences (1998),...

Critic, Literary Scholar, Poet Kachkynbai Artykbaev

Critic, literary scholar, poet K. Artykbaev was born in the village of Keper-Aryk in the Moscow...

The Poet Baidilda Sarnogoev

Poet B. Sarnogoev was born on January 14, 1932, in the village of Budenovka, Talas District, Talas...

Poet, Linguist Kasym Tynystanov

Poet and linguist K. Tynystanov was born on September 9, 1901—November 6, 1938, in the village of...

Poet Karymshak Tashbaev

Poet K. Tashbaev was born in the village of Shyrkyratma in the Soviet district of the Osh region...

The Poet Gulsaira Momunova

Poet G. Momunova was born in the village of Ken-Aral in the Leninpol district of the Talas region...

Critic, Literary Scholar Abdyldazhan Akmataliev

Critic and literary scholar A. Akmataliev was born on January 15, 1956, in the city of Naryn,...

Poet, Prose Writer Kubanychbek Adamaliev

Poet and prose writer K. Adamaliev was born in the village of Kochkorka in the Kochkorka district...

Poet Abdravit Berdibaev

Poet A. Berdibaev was born on 9. 1916—24. 06. 1980 in the village of Maltabar, Moscow District,...

Jursun Suvanbekov

Suvanbekov Jursun (1930-1974), Doctor of Philological Sciences (1971) Kyrgyz. Born in the village...

Prose Writer Kachkynbay (KYRGYZBAI) Osmonaliev

Prose writer K. Osmonaliev was born on March 5, 1929, in the village of Chayek, Jumgal district,...

The Poet Tenti Adysheva

Poet T. Adysheva was born in 1920 and passed away on April 19, 1984, in the village of...

Zhumash Mamytov

Mamytov Jumash (1935), Candidate of Philological Sciences (1967), Professor (2001) Kyrgyz. Born in...

Poet, Journalist Barktabas Abakirov

Poet and journalist B. Abakirov was born in the village of Kum-Dyube in the Kochkor district of...

Critic, Literary Scholar Abdygany Erkebayev

Critic, literary scholar A. Erkebayev was born in the village of Kara-Teyit in the Alaï district...

The Poet Akbar Toktakunov

Poet A. Toktakunov was born in the village of Chym-Korgon in the Kemin district of the Kyrgyz SSR...

Poet, storyteller-manaschi Urkash Mambetaliev

Poet, storyteller-manaschi U. Mambetaliev was born on March 8, 1934, in the village of Taldy-Suu,...

Moods and Function Words in the Kyrgyz Language

Moods in the Kyrgyz Language The Kyrgyz language presents the following moods: imperative,...

Poet, Prose Writer Anatoliy Omurkanov

Poet and prose writer A. Omurkanov was born on June 2, 1945, in the village of Chesh-Dyube, Manas...

Karymshakov Rakhym Karymshakovich

Karymshakov Rakhym Karymshakovich (1936), Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences (1995),...

The Poet Sooronbay Jusuyev

Poet S. Dzhusuev was born in the wintering place Kyzyl-Dzhar in the current Soviet district of the...

Poet, Prose Writer Mar Aliev

Poet and prose writer M. Aliev was born on July 14, 1932, in the village of Kochkorka, Kochkorka...

The Poet Subayilda Abdykadyrov

Poet S. Abdykadyrova was born in the village of Sary-Bulak in the Kalinin district of the Kirghiz...

Salamatov Zholdon

Salamatov Zholdon (1932), Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences (1995), Professor (1993)...

Poet Abdilda Belekov

Poet A. Belekov was born on February 1, 1928, in the village of Korumdu, Issyk-Kul District,...

Poet Dzhaparkul Alybaev

Poet Dzh. Alybaev was born on October 12, 1933, in the village of Birikken, Chui region of the...

Poet, Prose Writer Tash Miyashev

Poet and prose writer T. Miyashev was born in the village of Papai in the Karasuu district of the...

Population of Kyrgyzstan as of January 1, 2013

Population of Kyrgyzstan Thanks to the fundamental changes that occurred in Kyrgyzstan after the...