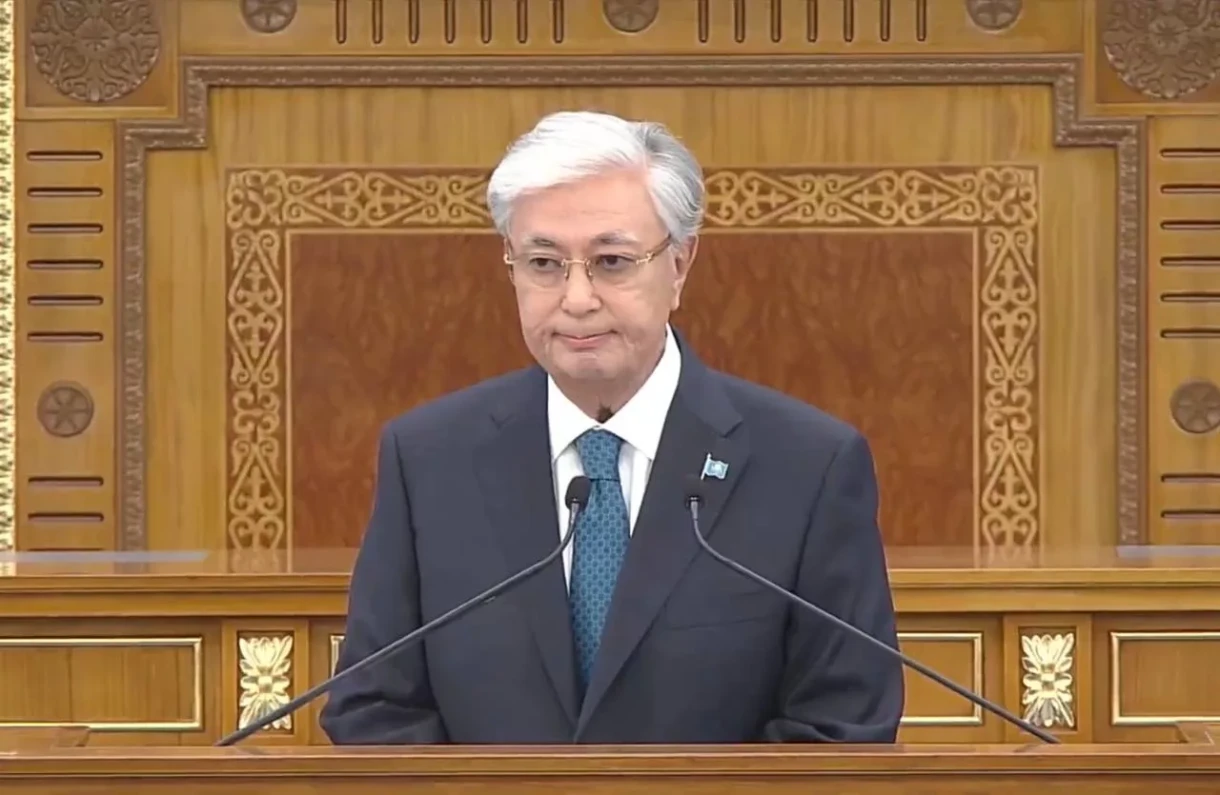

Kazakhstan has already had experience with the vice-presidency, but it abandoned this position for certain political reasons. Kassym-Jomart Tokayev proposes to reinstate it in a modified format. However, the only vice president who held this position 25 years ago explained why it became undesirable for the new power system, reports exclusive.kz.

The vice-presidency in Kazakhstan was introduced in the early 1990s when the country was just beginning to form a new political system. In 1990, the Supreme Council established the position of president, and shortly thereafter, the post of vice president was created.

This model borrowed heavily from the American system, where the vice president is considered the second person in the state and a potential successor to the president, serving as an important element of political stability and continuity.

Sergey Tereshchenko became the first vice president of the Kazakh SSR, but after the first presidential elections in December 1991, he was replaced by Yermek Asanbayev, who at that time held important positions in parliament and the government. Tereshchenko became the prime minister.

Shortly after that, the republic gained independence, and the vice-presidency became part of the new constitutional structure aimed at a smooth transition from the Soviet system to a presidential model of governance.

The 1993 Constitution granted the vice president certain powers, including performing the functions of the president at his direction and substituting for him in case of absence. This position was conceived as a mechanism for the continuity of power, capable of mitigating political crises and ensuring a stable transfer of power.

However, in practice, the vice president never became an independent center of influence. This position quickly came to be seen as nominal, and its existence began to threaten the consolidation of presidential power. The very idea of the vice presidency reminded that the president is not the only one, and the power system allows for the presence of a successor.

As a result of constitutional changes in the mid-1990s, the vice presidency was abolished. At the same time, the Constitutional Court was also eliminated, which contributed to the strengthening of presidential powers and new political structures.

Yermek Asanbayev, the first and only vice president, shortly before his death explained why this position was created and why it became inconvenient in the post-Soviet system.

"A Limitation on the Path to a Personal Power Regime"

In 2000, the "Witnesses" project published an extensive interview with Asanbayev, which was later published on the Exclusive.kz website in 2009. This conversation is now perceived as the political testament of a man who deeply understood the mechanisms of power and saw how a new governance system was forming in post-Soviet Kazakhstan.

In response to questions about the abolition of the vice presidency and its possible revival, Asanbayev explained that this position was not intended to be auxiliary or ceremonial, but rather as an important element of the political structure.

"The institution of the vice presidency was ideally created to facilitate the transition of power and as one of the obstacles to the formation of a personal power regime or dictatorship. It can function successfully in civilized countries with a high political culture and good relationships among people," he emphasized.

Thus, at the initial stage, the vice president was not seen merely as an assistant to the president, but as an element of a system of checks and balances that ensured a smooth transfer of power and prevented its concentration in one person's hands.

However, Asanbayev immediately noted that such a model requires a corresponding political environment, which was absent in post-Soviet countries. This became the main reason for the failure of the idea itself.

"In the post-Soviet space, the model 'president - vice president - prime minister' turned out to be ineffective. But, in my opinion, real power is concentrated in the hands of the prime minister, and his integrity is of immense importance to society," he added.

This formula to some extent became a diagnosis of the governance system in Kazakhstan at that time. It featured several centers of power, between which there were no clear boundaries or mechanisms for the division of powers, leading to internal competition and conflicts.

Asanbayev emphasized that despite its formal significance, the vice president had no real power. He pointed out the main drawback of this position: the ambiguity of its powers and the absence of mechanisms for their implementation.

"The powers of the vice president in our Constitution were not clearly defined, and there was no clear mechanism for their realization..."

Thus, in 2000, Asanbayev effectively acknowledged that the idea of the vice presidency was correct, but the political system was not ready for it.

"The Desire to Leave a Mark in History, and Then Use Opportunities"

Speaking about the transformation of post-Soviet elites, Asanbayev described a mechanism that became characteristic of many states in the region. He emphasized that the main problem lies in the temptation of power, which blurs any institutional constraints.

"It cannot be claimed that the violation of moral principles began with the first steps. In my opinion, at first, many experienced a duality of goals: on the one hand, the desire to enter history as a brilliant reformer, and on the other – to take advantage of opportunities for illegal enrichment," he noted.

Importantly, Asanbayev did not reduce the problem to the personal qualities of leaders, but pointed to the deformation of the power system itself, where the rhetoric of reforms gradually gave way to the logic of personal enrichment.

The first vice president of Kazakhstan rejected the popular opinion that politics is inevitably a dirty business.

"I do not agree that politics is a dirty business. This opinion is propagated by those who want to justify their unsightly actions. Politics is a high profession of serving one's society," he emphasized.

In his view, since politics is a "high profession," it requires institutions of checks and balances. It was precisely the absence of such institutions that he considered the main problem of post-Soviet regimes. The vice presidency, in this context, was not just a position, but an element of a structure that prevented the concentration of power in one person's hands. Therefore, this structure proved incompatible with the presidential vertical.

Reasons for Abandoning the Vice Presidency

The official abolition of the vice presidency occurred during a constitutional reform aimed at "optimizing" the system. However, the actual reasons for this decision were more political than procedural.

In the article "Yermek Asanbayev: the one who brought Nazarbayev to power while remaining in his shadow" in 2023, Exclusive.kz analyzed in detail why his figure began to be perceived as a potential threat. The very position of vice president became a reminder that the president is not the only one, and power can be transferred not only through elections but also through institutional mechanisms.

In the early 2000s, Nazarbayev needed not just strong presidential power, but unilateral power. In this structure, any formal "steps" to the presidential chair became potentially dangerous, even if their holder had no ambitions. The existence of an institutional deputy head of state was perceived as a limitation for the emerging vertical.

Thus, the vice presidency became a symbol of a possible alternative to power, and that is why two main limitations of the presidential vertical were eliminated – the post of vice president and the Constitutional Court. Formally, this was explained by the optimization of the system, but in fact, the possibility of institutional competition was removed.

After the abolition of the position, Asanbayev found himself in diplomatic "exile" and returned to the country only in 2000, already as a retiree, and four years later he passed away.

The Difference Between Tokayev's Vice President and Nazarbayev's

Today's discussions show that it is not the institution that Asanbayev spoke of that is being restored, but a fundamentally new version of it.

In the 1990s, the vice president was elected, viewed as a formal successor and an element of the power transition, which made him politically inconvenient for a system based on unilateral presidential power.

In the new model, the vice president will be appointed, and his powers will be defined by the president.

In essence, he will not be seen as a potential successor, but will become part of the presidential administration, continuing the existing vertical. This is not a restoration of the old institution, but the creation of a new position – an administrative deputy head of state, embedded in the already existing governance system.

Thus, history is returning, but in a completely different form. It is not a mechanism for ensuring continuity and checks, as Asanbayev spoke of, that is being restored, but its distorted version, devoid of the role for which this position was created. The vice president will no longer be part of the system limiting personal power but will become yet another level of presidential architecture.

Perhaps that is why it is worth revisiting the words of the man who understood best why this institution was needed: not for the convenience of the apparatus, but as a protection against the personalization of power and as a means to prevent the system from closing in on one person.

In one of his last interviews published on the Exclusive.kz website, Yermek Asanbayev uttered almost prophetic words: "A country without conscience is a country without a soul, and a country without a soul is a country doomed not to survive."

In his understanding, the "conscience" of the state is not an abstract morality but the ability of power to limit itself with institutions, not to substitute rules for personal will, and not to destroy mechanisms of succession for tactical convenience. This meaning was embedded in the idea of the vice presidency, and today it disappears behind the familiar name of the returning position.