Aeon: How the Conquest of Foreign Territories Came to Be Considered Unacceptable

Author: Kerry Goettlich

In the modern world, where consensus on many issues is becoming increasingly rare, there is one indisputable assertion. Almost all countries, in one way or another, recognize the importance of respecting the "sovereignty and territorial integrity" of other states as a fundamental principle of international relations. According to the UN Charter, which was ratified in 1945, states are obligated to refrain from "the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state." It is important to note that in this text, the term "state" is used instead of the more nebulous concepts of "nation" or "country," as it refers specifically to independent political entities, rather than subordinate units such as states within the USA.

In our time, it is difficult to find a person who openly supports the idea of the legitimacy of annexing the territory of another state through violence. Although conquests continue to exist, they manifest in more disguised forms.

Modern political figures take pride in rejecting conquest as unacceptable, which gives the current international order an appearance of civilization and peace. What can justify the violent seizure of foreign territories? Nevertheless, the notion that conquest can never be justified in international affairs is a relatively new idea. As the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius argued in the 17th century, peace treaties that end wars must be upheld, even if they impose unjust conditions, such as the seizure of part of a state's territory. Such treaties, however unjust they may be, sometimes become the only way to end a conflict, and their non-recognition would jeopardize peaceful resolutions. Moreover, as the American jurist Henry Wheaton emphasized in the 19th century, "the rights of most European nations to the lands they currently control originally arose from conquest, subsequently confirmed by long possession." From this perspective, the existence of almost any state depends on the legitimacy of its conquests.

However, instead of Grotius's concept of "the rights of peoples," aimed at limiting conquests, today we have an international system that guarantees the absolute right of each state to its current borders. It is prohibited to benefit from conquests made after approximately 1945, or later, when it comes to territories seized by colonial powers from new independent states. Consequently, conquests that occurred before a certain historical moment are considered fully legitimate, while modern conquest is regarded as one of the gravest crimes.

How did we arrive at an international order that so radically protects the status quo?

The prohibition of annexation through conquest has resulted from a combination of many factors. Paradoxically, states capable of large-scale conquests often oppose them. It is not surprising that those who have become victims or those who may become victims condemn conquest. But it is much more interesting to consider why, for instance, the United States, possessing the most powerful army in the world, opposes annexation through conquest. The USA maintains a military presence on all continents and often uses force; however, since the annexation of the Northern Mariana Islands, seized during World War II, it has not annexed conquered territories. Why does the sole global superpower voluntarily limit itself?

A part of the answer lies in the history of the formation of the USA, which dates back to a particular type of colonialism based on a thirst for land ownership, plantation slavery, and later agricultural and industrial capitalism. Until 1900, the USA engaged in continuous territorial expansion. Essentially, they were similar to many empires, but differed in that their conquests were largely carried out by settlers acting on their own initiative. Even before gaining independence, when the USA was part of the British Empire, authorities sought to restrain expansion, as it already led to costly wars and threatened the stability of the European state system. After gaining independence, the federal government of the USA was less committed to adhering to territorial agreements with indigenous peoples, although it could not fully control the chaos caused by the westward advance of settlers.

Interestingly, many future states, such as California, Florida, Hawaii, Texas, and Vermont, experienced a brief period of independence before joining the USA. And these are just successful examples; in the Appalachians, numerous "quasi-states" arose that never received official recognition, with names like Vandalia, Watauga, Transylvania, and Westsylvania.

Thus, conquest has always been an important part of the history of the USA, albeit in a different form than in the European colonial empires against which they rebelled. While the federal government encouraged settlement, the driving force behind expansion seemed to be the inevitable advance of settlers westward. But is this form of conquest fundamentally different from the European imperialism that the USA declared complete in the Western Hemisphere in the Monroe Doctrine? By the 1890s, settler expansion had reached Hawaii, and the possibility of creating a European-style overseas empire became real for the USA. The question of the nature of the American empire became a subject of active debate.

In the 1890s, conquest found itself between the principles of laissez-faire and liberal egalitarianism. Americans at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries debated what their imperialism should look like. Historians often describe this dispute as a confrontation between "imperialists," such as naval officer and historian A.T. Mahan, and "anti-imperialists," such as conservative sociologist William Graham Sumner. However, they had much in common. For both Mahan and Sumner, the conquests of Spain were unacceptable, as they contradicted the freedom and initiative that they believed were the foundation of viable nations. Sumner argued that the seizure of the Philippines was equivalent to "the conquest of the United States by Spain," as colonial expansionism could undermine American politics. Mahan, while supporting the creation of a strong navy and the expansion of US influence in Hawaii and the Panama Canal zone, also viewed Spanish policy as an example of "wrong" imperialism. Spain sought wealth by "digging gold out of the ground" and sending it to the metropolis, then buying goods from other countries. In contrast, according to Mahan's views, "colonies develop best when they grow on their own, in accordance with the character and ambitions of their settlers." These views reflected the unique path of US settler expansion before 1900.

When American settlement covered the entire continent, the next step became unclear. As Sumner noted, conquest in the 1890s was caught between the free market and the principle of equality. If the conquered people are "civilized," then there is no need for conquest — all benefits can be obtained through trade. If they are "uncivilized," then establishing authority over them undermines the doctrine that "all men are created equal."

The USA resolved this contradiction by developing a unique type of imperialism: from settler to one where trade and business became the main drivers, at least theoretically. The new American imperialism relied on the old in the sense that it was not directly governed by a centralized state or imperial center. Instead of farmers and settlers of the 19th century, the main agents of 20th-century expansion became exporters and railroad magnates. Their economic activity abroad, American leaders argued, was supposed to bring prosperity within the country and mitigate class conflicts.

The plan for the new imperialism was outlined in the so-called "Open Door Notes" of 1899 and 1900. The "Open Door" policy represented a diplomatic offensive by the USA against outdated European imperialism in China and was intended to pave the way for American business. In the 1899 note sent by Secretary of State John Hay to the capitals of the great powers, the right of all states to trade in China on equal terms was asserted. The second note, sent in 1900 against the backdrop of the Boxer Rebellion, proclaimed the USA's desire for peace in China, the preservation of its "territorial and administrative integrity," the protection of American rights, and the provision of "the principle of equal and impartial trade."

From the beginning of the 20th century, the USA consistently supported the Open Door policy in China. In 1915, Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan stated that the USA would not recognize any agreements "that infringe upon the treaty rights of the United States and its citizens in China, the political or territorial integrity of the Republic of China, or the international policy known as the Open Door policy." After World War I, this policy became the basis for the Nine-Power Treaty of 1922, in which the USA, Great Britain, Belgium, China, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, and Portugal pledged to "respect the sovereignty, independence, and territorial and administrative integrity of China."

Immediately after the Spanish-American War of 1898, during which the USA conquered the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam, American officials began to publicly oppose annexations. Roosevelt's Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, asserting the right of the USA to intervene in the affairs of Western Hemisphere countries to maintain order, was accompanied by assurances that "the United States does not thirst for land... all this country desires is to see its neighboring states stable, orderly, and prosperous." In 1906, Secretary of State Elihu Root embarked on a tour of South America, repeating formulas like: "We do not desire victories, except victories of peace; we do not desire any territory except our own; we do not desire any sovereignty except sovereignty over ourselves."

However, during this period, US interventions in Latin America sharply increased. Under President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909), the USA took control of the Panama Canal (1903), occupied Cuba (1906–1909), and intervened in the affairs of the Dominican Republic (1904) and Honduras (1903 and 1907). But after more than a century of territorial expansion — through purchases and conquests at the expense of European empires, indigenous peoples, and settler republics — the USA officially renounced territorial conquests.

The concept of the abolition of conquests is not always associated with the USA and its informal imperial aspirations. In recent years, experts from leading think tanks have begun to link the principle of territorial integrity with what they call "the rules-based international order." Its origins are usually traced to the establishment of the UN after World War II, when the world sought to learn lessons from catastrophe and build a more peaceful order. Many researchers also point to the League of Nations Covenant of 1919 as the beginning of the renunciation of conquests: Article 10 promised to "respect and preserve from external aggression the territorial integrity and existing political independence of all members of the League." What role did the Open Door policy play in this?

To understand this, it is necessary to see how contradictory and ambiguous Article 10 was from the very beginning. In the USA, it became the main reason for the Senate's refusal to join the League of Nations: there was a risk that it would obligate the country to intervene in foreign wars. Canada repeatedly attempted to soften or exclude this article. Why should the Canadian army take on the responsibility of maintaining all world borders, many of which may be unjust and which some peoples have the right to seek to change?

In January 1923, France invaded and occupied the Ruhr in response to Germany's failure to pay reparations. In August of the same year, Italy seized the Greek island of Corfu after the murder of an Italian general. France feared that the League's improper intervention in the Italo-Greek conflict would draw attention to its own occupation of the Ruhr. What did Article 10 mean in such situations?

The Permanent Advisory Commission of the League of Nations likely took these complexities into account when, in the same year, it attempted — and failed — to negotiate a more precise definition of "aggression." Delegates from France, Belgium, Brazil, and Sweden argued that the old understanding of aggression as a simple crossing of a border had lost its meaning in the context of modern warfare and proposed a more complex concept that took various factors into account. This, of course, would protect France from automatic blame for the occupation of the Ruhr. Britain, fearing that its weakened military resources would be drawn into conflict with the USA, effectively halted all attempts by the League to define aggression. Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald expressed the opinion that any definition of aggression would become merely "a trap for the innocent and a guide for the guilty." By the end of the 1920s, the meaning of Article 10 remained extremely unclear.

By the 1930s, the situation changed: uncertainty gave way to panic. The Wall Street crash of 1929 led to a global depression, Britain abandoned the gold standard, Japan conquered Manchuria and established the puppet state of Manchukuo, and in 1933, Hitler came to power in Germany. Global conditions forced the League of Nations to seek greater clarity.

Enter US Secretary of State Henry Stimson — a Harvard Law School graduate and member of the secret society "Skull and Bones" at Yale, a descendant of one of the Founding Fathers of the USA, Roger Sherman. Stimson closely monitored Japan's actions in Manchuria, seeking to maintain the Open Door policy. Initially, Washington's position resembled Britain's: Japan and China had their arguments, and the best that could be done was to reach an agreement. However, Stimson went further and concluded that Japan had crossed the boundaries of behavior for a "responsible great power." It was not merely protecting its interests around the South Manchurian Railway, as it claimed, but was establishing political control over all of Manchuria and bombing cities far from the railway zone.

Failing to gain support for tough measures, Stimson took a decisive step: he sent a diplomatic note that effectively reiterated Bryan's position, but with much broader implications. The USA refused to recognize any agreements or situations that arose in violation of the treaty rights of the United States, including violations of the territorial and administrative integrity of China and the Open Door policy. This position became known as the Stimson Doctrine — the doctrine of non-recognition of conquered territories. Through the decisions of the Council and Assembly of the League of Nations, the Non-Aggression Pact of 1933, and subsequent agreements, the principle of non-recognition of conquests became a norm of international law and remains so to this day.

Why did the Stimson Doctrine of 1932 become international law, while a similar note from Bryan in 1915 was ignored? One reason was that Japanese aggression extended beyond Manchuria and affected Shanghai, where European powers had significant interests. But more importantly, in 1915, the USA was a peripheral power, whereas World War I transformed it into a key force, eliminating many competitors. British diplomats were skeptical of the doctrine of non-recognition, considering it excessively moralistic and alien to British tradition. However, by the early 1930s, Britain was managing a declining empire and became more vulnerable.

British Foreign Secretary Sir John Simon sought to avoid disaster by trying to please everyone — the USA, the League, and Japan simultaneously. When Stimson attempted to achieve collective affirmation of the principles of the Open Door, Simon found a compromise: he allowed the League of Nations to voice the doctrine of non-recognition while avoiding sanctions. On February 16, 1932, the League Council approved a statement that included the Stimson Doctrine. All parties were relatively satisfied: Stimson received support, the League gained principle, and Japan avoided punishment.

Nevertheless, in Manchuria itself, the doctrine changed little. Moreover, the occupation of Manchuria became merely a prologue to World War II — the greatest war of conquests in history. It did not stop Italy from seizing Ethiopia and did not prevent Japan from further aggression in China and the Nanjing Massacre.

Why is it important to remember that the modern prohibition on conquests is largely a result of informal American imperialism? One answer relates to changes in US foreign policy under Donald Trump. In 2019, the USA was the first to recognize Israel's de facto annexation of the Golan Heights.

Rhetoric matters, especially when followed by actions. However, the significance of changes in US policy also depends on the reactions of other countries. The prohibition on conquests has never been an exclusively American project; it has been supported by the interests of most states seeking to avoid conquest.

The principle of territorial integrity is complex. In Woodrow Wilson's interpretation, it meant a prohibition on annexation but not on armed intervention. This narrow interpretation re-emerged during the US and allied invasion of Iraq in 2003, when respect for territorial integrity meant maintaining borders but not refraining from military control.

Today, this narrow interpretation suffers the most from recent annexations. Conquest remains illegal, but its moral weight may diminish. International orders come and go. Until now, there has been an order in which conquest was regulated but not prohibited. A new order will inevitably emerge — and it is increasingly unlikely that attitudes toward conquests will be shaped by the ideological constructs of the USA.

Original: Aeon

Read also:

Venezuela condemned Trump's statement on closing the country's airspace

In its statement, Venezuela emphasized that Trump's actions represent extraterritorial...

The Cabinet expanded the powers of the Ministry of Emergency Situations in the field of public safety.

The Cabinet of Ministers approved changes to the operational rules of the Ministry of Emergency...

Sadyr Japarov congratulated Kyrgyzstani people on Human Rights Day

President Sadyr Japarov, in his address to the citizens on the occasion of Human Rights Day,...

Legislative Foundations for the Creation and Functioning of the Military Security Assurance System of the Kyrgyz Republic

Not considering any state or coalition of states as its adversary, and opposing the use of...

An event in memory of the Batken events took place in Sokuluk.

Yesterday, October 24, an event was held in the central square of the rural district of Sary-Özön...

The CEC announces the acceptance of documents from citizens and political parties for the BTIC reserve

The Central Election Commission (CEC) has announced the start of accepting documents from citizens...

Secretary of State of the Kyrgyz Republic: The Epic of "Manas" - the embodiment of civic duty, patriotism, national unity, and the integrity of the state

Arslan Koichiev congratulated the people of Kyrgyzstan on the Day of the Epic 'Manas' On...

"The New Year Should Become a Symbol of Unity for Post-Soviet States"

At the international conference "Trends in the Development of the System of International...

Elections in the Housing Sector. Bishkek City Election Commission is replenishing its reserve

The Central Election Commission (CEC) has announced the start of document collection from citizens...

Sadyr Japarov signed a law regarding mutual assistance between CSTO countries during disasters

President Sadyr Japarov signed a law titled "On the Ratification of the Agreement on the...

The Constitutional Court of the Kyrgyz Republic deemed the reinstatement of the death penalty in the country unacceptable.

On December 10, the Constitutional Court of Kyrgyzstan reviewed the president's submission...

Social Structure and Development Challenges of Pakistan: 78 Years After Independence

Since gaining independence in 1947, Pakistan has undergone numerous political and social changes....

In 2024, 167 environmental defenders were killed worldwide

This year, the number of murdered environmental defenders has reached 167, according to data...

Renovation in Bishkek. Authorities intend to resolve the issue of "one dissenting individual"

According to information voiced by Deputy Minister of Construction, Architecture, and Housing and...

To Execute or Not to Execute: How Kyrgyzstan Decided Where to Place the Comma

On December 10, the Constitutional Court of Kyrgyzstan issued a ruling that definitively closed the...

The 50th session of the Working Group on General Debate on the Human Rights Situation begins in Geneva at the Human Rights Council.

In accordance with resolution 60/251 of the UN General Assembly, adopted in 2006, all member...

In the Batken Region, the resettlement of residents from border areas has been completed. The parties exchanged property inventory acts.

In the Batken region, the process of relocating residents from border villages adjacent to...

Turkic states seek to strengthen economic and trade ties with the EU, - Secretary General of the Turkic Council Omuraliyev

Kubanychbek Omuraliev The Alliance of Turkic States is becoming an economic power due to growth,...

What the 2025 U.S. National Security Strategy Means for Asia

The Trump strategy demonstrates characteristic features of MAGA, including an emphasis on national...

In Kyrgyzstan, the memory of the soldiers who died in the Batken events was honored

An event was held in Kyrgyzstan in memory of the soldiers who died during the Batken events. The...

ICJ Welcomes the Decision of the Constitutional Court of the Kyrgyz Republic on the Death Penalty

The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) expressed approval regarding the recent decision of...

Foreign Policy Aspects of Ensuring the Military Security of the Kyrgyz Republic

The insufficiency of military means to ensure external security is something Kyrgyzstan tries to...

The star of "Mortal Kombat" Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa has died

Famous actor of Japanese descent Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa passed away on December 4, at the age of 75....

The Vice President of the USA called the vote in the Israeli parliament on the annexation of the West Bank an insult.

On Wednesday, hardline supporters in the Knesset initiated a preliminary vote on the annexation of...

Sergey Masaulov: The New Ideology of Kyrgyzstan - "Mercantilist Indifference"

With each passing day, issues of information security are becoming increasingly relevant. Daily,...

The Foreign Policy of Sovereign Kyrgyzstan

Sovereign Kyrgyzstan is an equal member of the international community. One of the most important...

The Foreign Policy of Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan is a state in the Central Asian region, whose location has significant geopolitical and...

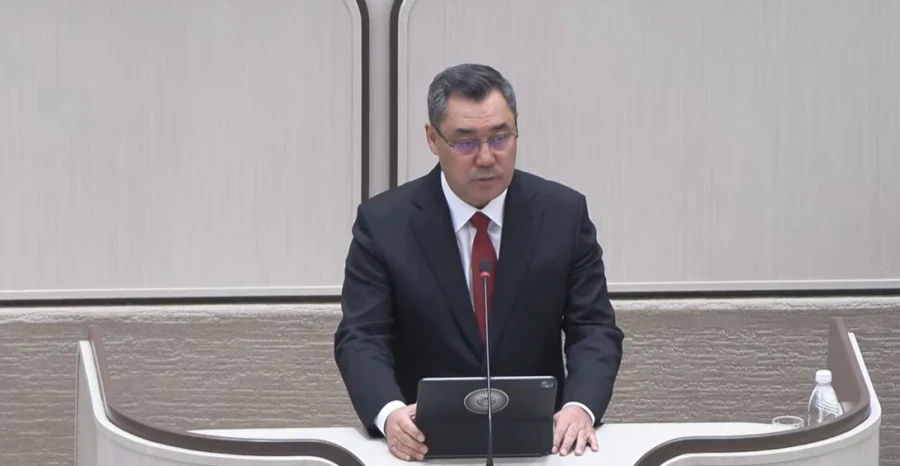

Sadyr Japarov: There Were Lobbyists, Corruption, and Even Representatives of Organized Crime Groups in Parliament

The President made a statement at the first session of the VIII convocation of the Jogorku Kenesh...

Trump stated that Ukraine must agree to the peace plan by next Thursday

According to CNN, this information was voiced in an interview with Trump on Fox News. The president...

Secretary of State of the Kyrgyz Republic Marat Imankulov on the role of the CSTO: "Unity is our strength"

Against the backdrop of global instability, Kyrgyzstan is preparing for the CSTO summit scheduled...

Economic growth has also been made possible thanks to the work of diplomats. Congratulations from the head of the Cabinet.

On the professional holiday — the Day of the Diplomatic Service Worker of the Kyrgyz Republic —...

O. Karaev. The Chagatai Ulus. The State of Haidu. Moghulistan

History of the Chagatai Ulus (13th century), the state formations of Haidu (13th—14th centuries),...

Ombudsman: The Return of the Death Penalty Contradicts the International Obligations of the Kyrgyz Republic

A recent working meeting of the Ombudsman of Kyrgyzstan, Jamilya Jamangbaeva, UN Resident...

The Russian Federation has taken on an indefinite commitment not to impose the death penalty - Ministry of Foreign Affairs

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) has published an official statement regarding the recent...

European leaders criticized the "peace plan" for Ukraine and demanded its revision

In a joint statement published by the EU Council press service, it is reported that the proposed...

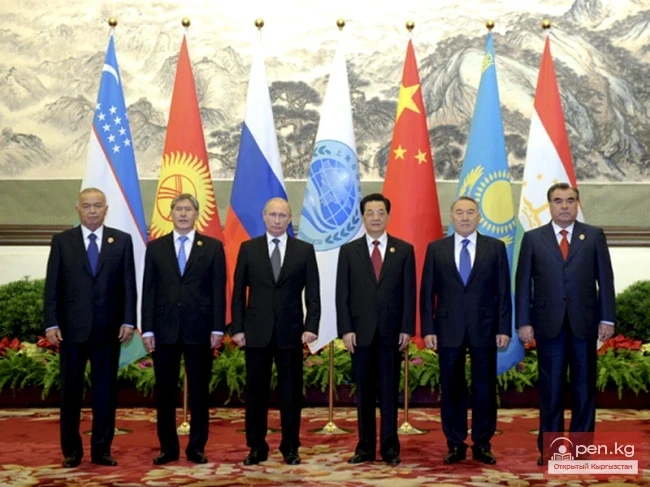

President Almazbek Atambayev congratulated athletes on their successful performance at international competitions and awarded them monetary prizes.

Today, October 22, 2014, President of the Kyrgyz Republic Almazbek Atambayev congratulated the...

Why BRICS is Strengthening Despite US Threats

Since its inception, BRICS has not lost a single member; on the contrary, its membership has only...

Usuni in Prissykul

Usuns This text will discuss the people of the Usuns. Few Central Asian-Kazakh ethnonyms have such...

Governance in Ancient Kyrgyzstan Before the 6th Century

Kyrgyzstan is one of the world’s centers of human emergence, statehood, and civilization. The life...

Singer Mariah Carey will perform at the opening of the 2026 Olympic Games

At the opening of the Winter Olympic Games, which will take place in 2026 in Italy, the famous...

President of the Kyrgyz Republic Almazbek Atambayev awarded presidential scholarships to outstanding students of the country's universities.

President Almazbek Atambayev: “The pursuit of knowledge is the key to success in the modern...

Debate in Bishkek on the Reinstatement of the Death Penalty: Protection of Society or Violation of Rights?

Recent public hearings organized by the Media Action Platform of Kyrgyzstan became a platform for...

In Kyrgyzstan, it is necessary to tighten criminal liability for terrorism.

To protect the Kyrgyz Republic from external threats, among other things, the introduction of new...

Planning of Military Construction in the Kyrgyz Republic

The invasion of illegal armed formations of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan into the southern...

The Constitutional Court deemed the reinstatement of the death penalty unacceptable.

On December 10, 2025, the Constitutional Court of the Kyrgyz Republic discussed the...

Kekemeren River

Kekemeren River is one of the most amazing and beautiful rivers in Kyrgyzstan. The Kekemeren is...