Nazarbayev-Tokayev: Anatomy of Political Transformation

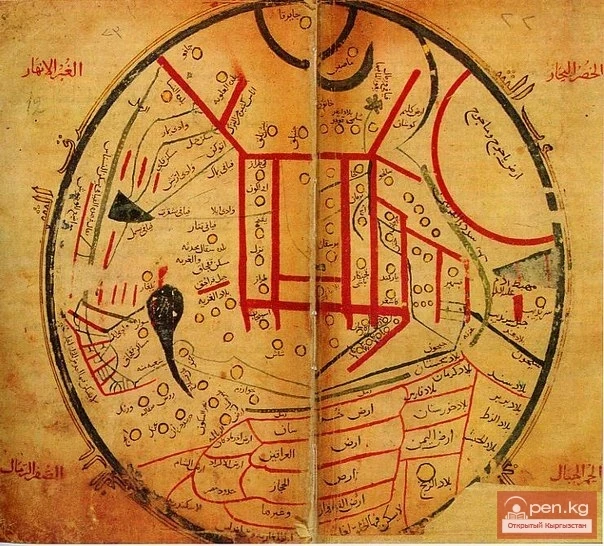

Recently, the term "asabiyya," introduced by the medieval Arab thinker Ibn Khaldun in the 14th century and actively used in Eastern philosophical and political thought, has increasingly appeared in political discussions. Unlike Western approaches, this concept focuses on the socio-psychological and humanitarian aspects that shape the idea of asabiyya as a unique form of social cohesion influencing historical events. What are the differences between the asabiyya of Nazarbayev and Tokayev? This question is addressed in an article on exclusive.kz:

Ibn Khaldun and his followers emphasized the cyclical nature of asabiyya characteristics as a key reason for the emergence, flourishing, and decline of states. Although the term itself translates to "collective solidarity," this definition does not fully capture its essence, as it implies the unification of human groups and communities that have attained power.

A vivid example of steppe asabiyya is the 26 companions of Genghis Khan, known as the "people of long will," who created the largest empire in history, which lasted more than six centuries until the Kazakh Khanate—the last remnant of this empire—ceased to exist in the 19th century. What was the strength and moral height of this nomadic solidarity that allowed it to endure for so long?

According to Ibn Khaldun's ideas, which asserted that a stable state begins to disintegrate due to internal conflicts after several generations, the empire of Genghis Khan also fell apart. This occurred both with empires and large states, and Ibn Khaldun scientifically substantiated his conclusions using examples from Arab monarchies. He developed the theory of asabiyya as a methodological approach to analyzing historical processes, which remains relevant today, as it is based on the unchanging nature of human behavior.

Researchers note that "asabiyya" embodies a high consciousness of unity, tribal and kinship spirit, which underlies social solidarity and group consciousness, resonating with Lev Gumilev's concept of passionarity.

At the beginning of 1917, the Bolshevik party, led by Lenin, was a small political group with radical views, but by the end of the year, it successfully staged a coup, attracting discontented masses with its slogans "Factories to the workers, land to the peasants, peace to the nations." However, after the end of the civil war and the leader's illness, deadly conflicts arose within the Bolshevik asabiyya.

One of the main reasons for the weakening of asabiyya, according to Ibn Khaldun, is the new leader's desire for a monopoly on power, leading to conflicts with former comrades. After victory, the power system quickly becomes hierarchical, and previous cohesion turns into mercenarism.

Stalin was the first to realize that he could not win by following the laws of asabiyya and created institutional tools—the party apparatus. Loyal Leninists were eliminated, and the ideas of world revolution disappeared. The asabiyya of revolutionary fanatics was replaced by the power of communist bureaucrats. Interestingly, Cuban leaders, after their revolution, willingly allowed Che Guevara to continue revolutionary activities in South America, as long as he did not create problems within the country.

This situation raises the question of the relationship between asabiyya and institutions. In the Soviet Union, party structures dominated until 1991, but this does not mean that the aspect of asabiyya disappeared. On the contrary, it manifested itself in the form of intra-party struggles and changes of leaders. The modern histories of China and Vietnam show that there operates a system of party asabiyya, which, despite its ideological and structural roots, has mechanisms for renewal and leadership change.

The Trump team can also be represented as asabiyya, with a pronounced will to power and the goal of "making America great again." However, it must interact with established institutions that have been functioning for over two hundred years and adapt to existing rules. Unlike the Arab dynasties studied by Ibn Khaldun, the White House is constrained by democratic institutions and American legislation.

The situation in Russia, as noted by popular blogger Savromat, is different; there, "Chekist asabiyya" dominates. The difference lies not only in the fact that Putin became the official successor to Yeltsin but also in the fact that the unifying idea chosen is an aggressive great-power paradigm that ignores international norms. The main distinction is that Putin's asabiyya fully controls all state institutions, including parliament and the judiciary, manipulating them and hiding its true existence behind their facade. In contrast, in America, everything is open, thanks to strong democratic traditions.

Modern political science has a multitude of terms to help analyze political processes—from political groups to movements and elites. But what is remarkable about the phenomenon of asabiyya? It reveals the deep mechanisms of the political process, taking into account not only ideological and economic aspects but also human factors such as social and psychological aspects. Thus, the phenomenon of asabiyya is a useful tool for analysis.

Ibn Khaldun analyzed the monarchical dynasties of the Arab East and had no concept of democratic institutions that emerged in Europe after the bourgeois revolutions, opposing themselves to monarchies and autocracies, where the aspect of asabiyya is most vividly manifested.

In general, it can be said that in countries with strong democratic institutions, asabiyya manifests itself less strongly, and vice versa. The negative associations associated with this phenomenon can be explained by this. Nevertheless, asabiyya never completely disappears, as it reflects a person's loyalty to a particular group of power. This aspect is also important for analyzing the recent history of Kazakhstan, centered around the figure of Nursultan Nazarbayev, the founder of the new state system.

Nazarbayev came to power within the CPSU, becoming the head of the republican party organization and the Supreme Soviet at a time when power was transitioning from party structures to the Soviets. During the collapse of the USSR, he legitimized his power through presidential elections, forming a group of like-minded individuals around him, often from the lower ranks, to avoid the emergence of their ambitions.

Ibn Khaldun asserted that the leader of the group that seizes power seeks to monopolize it. Nazarbayev did not have to struggle long for this, as the dissolution of the CPSU automatically stripped authoritative figures of their positions and status. The next step was to seize economic levers, which led to the replacement of "red directors" who resisted new trends with his people.

Although the competitive field seemed to be cleared, free elections among deputies led to the emergence of ambitious individuals with democratic views who did not support the concentration of power. However, Nazarbayev already had his own asabiyya, whose members held key positions, and he dissolved the Supreme Soviet twice due to its unyielding deputies. The final victory of Nazarbayev's asabiyya was achieved with the adoption of a new constitution in 1995, endowing the leader with super-presidential powers.

Why can the circle of the first president be characterized as asabiyya according to Ibn Khaldun's criteria? First, it is unity based on high goals—independence and the creation of a strong state, in the interests of which the asabiyya acted. There was also a charismatic leader with political intuition and high popularity. The unity of intentions and actions was especially evident in the early stages of the formation of asabiyya when the enthusiasm of the pioneers inspired society. However, this unity can be disrupted, as demonstrated by the cases of Serikbolsyn Abdildin's transition to opposition and Akzhan Kazhegeldin's emigration, which, however, only strengthened Nazarbayev's team.

Secondly, it is important to consider kinship ties. The core of Nazarbayev's asabiyya consisted of close relatives, as evidenced by their inviolability and impunity. For example, the behavior of Rakhat Aliyev, which caused a political crisis in 2001, did not have consequences for him. Later, family members were exempted from responsibility due to laws.

At the same time, the emergence of the "young Turks" signified a serious ideological split within the ruling circle. They realized that the strengthening of asabiyya threatened the official power institutions and advocated for democratic development, understanding the consequences that concentration of power could lead to in an autocracy. At one time, the Minister of Information Altynbek Sarsenbayev said: "It is good that we have Nazarbayev, who uses power moderately. But what will happen if a person with different views comes?"

An important ally of Nazarbayev during that crisis was the then-prime minister, now president Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, which undoubtedly influenced Nazarbayev's choice of successor.

Thirdly, a member of the community often does not analyze the legitimacy of the actions of the group to which they belong. According to Ibn Khaldun, they support its positions, regardless of whether this group is oppressed or oppresses others. Members of asabiyya place themselves above others, which can lead to decisions that ignore the interests of the majority of the population. In Kazakhstan's recent history, there are many such decisions, including privatization and contracts with foreign companies.

The fourth and perhaps most important sign is the ruling group's desire for wealth and luxury as indicators of status and power. The habit of prestigious consumption leads to the necessity of maintaining the achieved quality of life, which in turn results in the depletion of the treasury, increased levies, decreased economic activity of the population, and unrest, as Ibn Khaldun noted.

The fifth sign is the gradual replacement of ideological motivation with career ambitions. Power becomes hierarchical, and mercenarism, which lacks high goals, replaces high unity. This leads to a decreased ability of the state to respond to resource depletion and to decline.

Ibn Khaldun noted that a weakened ruling group tries to demonstrate its strength by organizing grand events and providing for its supporters to maintain their loyalty. Kazakhstanis have witnessed such practices for many years.

In reality, in Kazakhstan, asabiyya developed as a parallel, hidden power, consisting of people close to the leader who made crucial decisions, which were then transmitted to the level of state institutions for official endorsement. It acted as a central nervous system, invisible yet controlling all functions of the state.

Ibn Khaldun also asserted that there can be continuity between dying and new dynasties, and the founder of a new dynasty may inherit the customs of predecessors. Institutions can be renewed provided that there are forces left for development, the most important of which is the strength of asabiyya. Positive changes are often associated with new power. Observing our neighbors Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, one can notice positive changes due to shifts in political and economic rules.

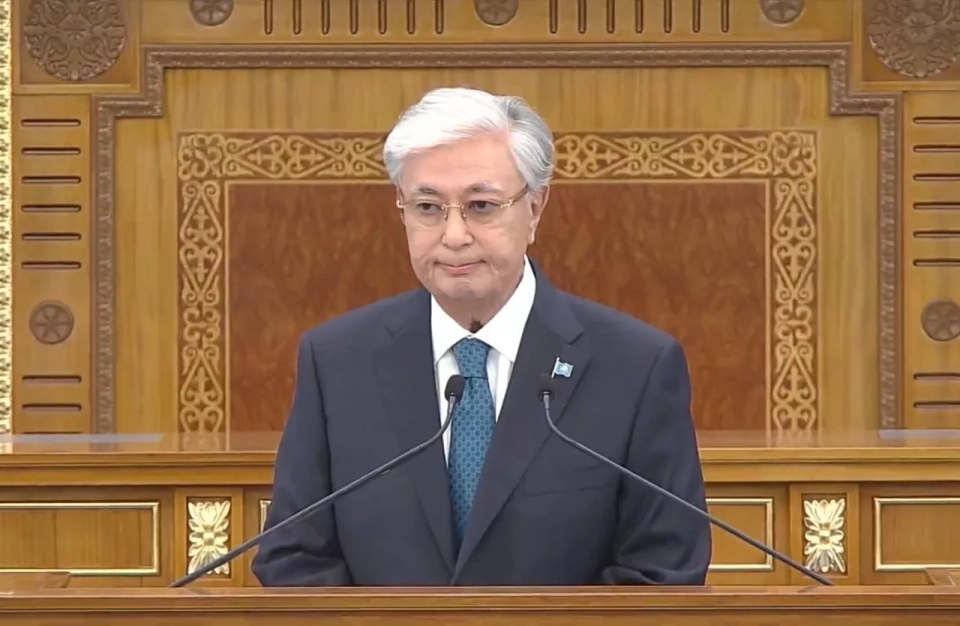

It is interesting how to assess the Kazakhstani power transition within the framework of the phenomenon of asabiyya. It is undeniable that Tokayev's asabiyya has replaced Nazarbayev's, and since the power did not change instantaneously but occurred through dual power, the confrontation between the old and new asabiyya was inevitable, leading to the events of January.

However, it is important for the nature of the ruling asabiyya to change, which is connected with key ideas that make it purposeful, and the goals—progressive and inspiring. Therefore, after Kantaru, President K. Tokayev made important statements about breaking with the recent past and building a New Kazakhstan, introducing new ideologies of a listening and just state, renewing personnel, and focusing on young professionals.

Nevertheless, consistency is important, and the leader must ensure that the new asabiyya is geared towards serious changes rather than preserving the old order, so that political modernization does not turn into manipulations of political technologies, and the new elite does not neglect the demands of the population. He must rein in the aspirations of the members of the new asabiyya for material prosperity, especially considering that it is the ruling layer that controls the distribution of the budget and state investments.

To date, it is clear that not everything is happening as the president intended. Tensions are also observed within the highest echelons of power. Public news from the fall of this year confirms that the agenda for 2029 is becoming increasingly relevant, and many believe that the main question will be resolved not through democratic procedures but according to the laws of asabiyya—by choosing a successor. This scenario implies much behind-the-scenes struggle and is fraught with unpredictability.

Therefore, an important task is to restore the balance disrupted during N. Nazarbayev's rule, which can be achieved by strengthening state and public institutions and implies political modernization with an emphasis on democracy.

One possible path could be President Tokayev's return to political leadership in the ruling party "Amanat," developing a new ideological platform and strategy aimed at deep reforms of electoral legislation, the judicial system, and local self-government, as well as revitalizing the political system and supporting economic and social freedoms. This extensive work can be aligned with key innovations in the new constitution.

High goals and ideological unity can unite a new progressive asabiyya and ensure its long-term support from society.

Yerlan Baizhanov

Diplomat, journalist

Read also:

Mukasov Smanaly Mukasovich

Mukasov Smanaly Mukasovich (1957), Doctor of Philosophy (2001), Laureate of the State Prize of the...

The Formation of the State of Moghulistan

THE STATE OF MOGULISTAN Since the formation of the empire of Genghis Khan, his descendants—the...

What is "slop"? The American Merriam-Webster Dictionary named it the word of the year 2025.

The American dictionary Merriam-Webster has recognized the term "slop" as the word of...

The son of the head of the KR, Kadyirbek Atambaev, developed Lev Gumilev's theory of passionarity.

Scholar Kadyrbek Atambaev, the son of Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambaev, has released a monograph...

Kyrgyzstan to Create a Multimedia Exhibition About Its History at the National Museum of Genghis Khan in Mongolia

The National Historical Museum has initiated a tender for the development of a permanent multimedia...

About Masimov, Tokayev's Fears, and the Chances for a Nazarbayev Clan Comeback

It will be extremely difficult for the representatives of the "Old Kazakhstan" to carry...

Population of Mogulistan

Arkanuts, Arlats, Barlasses The problem being studied is one of the complex and poorly researched...

The Cambridge Dictionary has chosen the adjective "parasocial" as the word of the year 2025.

The Cambridge Dictionary has announced that the word of 2025 is the adjective...

The State Committee for National Security reported how many marriages were registered between citizens of Kyrgyzstan and China over 5 years.

According to the press service of the State Committee for National Security (GKNB), since 2020, a...

Why is the President of Kazakhstan Strengthening Parliament and Purging His Inner Circle?

The discussion about the transit of power in Kazakhstan has become more active, despite the fact...

Kyrgyz Management System

POWER SYSTEM AND MANAGEMENT INSTITUTIONS According to historical sources, the Kyrgyz people went...

Who Will Not Be the Third. On the New Transition of Power in Kazakhstan

According to sources, preparations for the next power transition are actively underway in Akorda,...

The Origin of the Names of the Countries of the World. K-K

Kazakhstan. “Land of the Kazakhs.” From the name of the people, which, according to one version,...

Atambayev was reminded that greatness lies not in grievances, but in benefiting the country.

Political analyst Bakyt Baketaev believes that Kyrgyzstan needs to leave emotions and personal...

WT: Singer Elvis Presley found on the lists of sponsors for migrants arriving in the USA

A recent investigation conducted by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) revealed that...

Vanished Cities. Part 3

Ancient Cities Petra, Jordan The history of this unique city began in the 4th-3rd millennium BC,...

List of campaign materials and goods not prohibited for distribution among voters during the election period

The Central Election Commission on October 27 made a decision regarding the list of campaign...

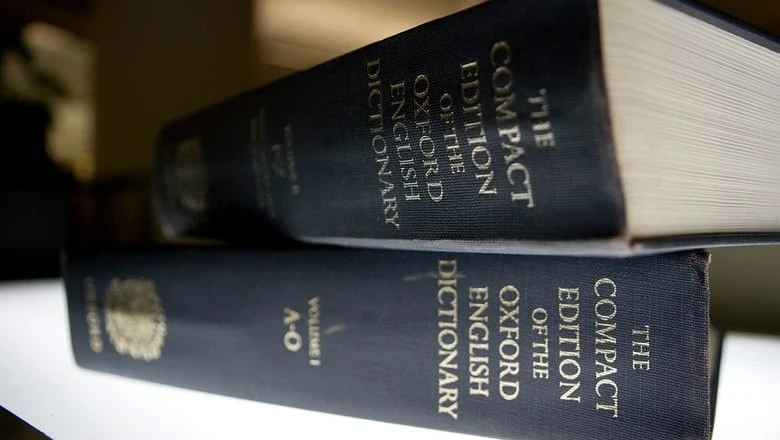

Ragebait. The Oxford Dictionary has named the Word of the Year 2025

In 2025, the word that received the status of "word of the year" according to the Oxford...

Amirchik made a "coming out" in a conversation with Sobchak. It's not what you think.

The famous Kyrgyz singer Amirhan Batabaev, better known as Amirchik, revealed some aspects of his...

The crisis can become an opportunity. Kyrgyz tailors are seeking new markets.

The export of sewing products to Russia has become a serious challenge for Kyrgyz producers. The...

Governance in Ancient Kyrgyzstan Before the 6th Century

Kyrgyzstan is one of the world’s centers of human emergence, statehood, and civilization. The life...

Tokaev: Kazakhstan Welcomes the Intensification of Negotiations on the Ukrainian Conflict

The President of Kazakhstan spoke at a forum in Turkmenistan...

A Study on Youth Presented in Bishkek

A presentation of the analytical review titled "Youth in the Kyrgyz Republic" took place...

The Education of Kyrgyz in the 6th to 18th Centuries

The Karakhanid period, as the apex of Turkic civilization, was a time when science and education...

Under the Chairmanship of the Heads of State, the 4th Meeting of the Supreme Intergovernmental Council of the Kyrgyz Republic and the Republic of Kazakhstan Took Place

On November 7, 2014, in the city of Astana, the 4th meeting of the Supreme Intergovernmental...

Narynbayev Aziz Isadjanovich

Narynbayev Aziz Isadjanovich (1924), Doctor of Philosophy (1970), Professor (1979), Corresponding...

In February, a social rehabilitation adaptation center for children is planned to open in Bishkek on the territory of the former 61st school.

Deputy of the Bishkek City Council Zhibek Sharapova raised an important issue regarding the...

Tokaev stated about the crisis of global trust and the need for UN reform

Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, the President of Kazakhstan, delivered a lecture at the United Nations...

The 20th Century — A Time of Forced Transition for Kyrgyz from Tribal Lifestyle to Soviet Order

FEATURES OF HISTORICAL CONSCIOUSNESS AND SOCIAL BEHAVIOR OF THE KYRGYZ IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY...

The new ambassador of Kyrgyzstan, Bazarbaev, presented copies of his credentials to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan.

During the meeting, as reported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan, issues...

Tokaev did not convey any messages or signals from Trump to Putin, - Kremlin

On November 11, Kassym-Jomart Tokaev arrived in Moscow, where on the first day of his visit he had...

The Oxford Dictionary has chosen the Word of the Year 2025

Illustrative photo The word "rage bait" has been chosen as the new word of the year by...

Putin promises to assist and support the leadership of Kyrgyzstan in achieving internal political stability

At a press conference in Bishkek held today, Russian President Vladimir Putin noted that the...

The longest shutdown in the USA has been overcome: senators managed to reach an agreement

U.S. senators have reached an important bipartisan agreement that will allow for the end of the...

The police are searching for distributors of the old video of the search in the house of Shailoobek Atazov.

On the Internet, especially in the Kyrgyz segment, a video has begun to circulate actively, showing...

"Ideological Intolerance". A Student from a Chinese University Expelled for Criticizing Marxism

The expulsion of a student from the physics department of Northwest University in Xi'an for...

Early elections to the State Duma. Heads of the Central Office of the Ministry of Internal Affairs sent to the regions

On November 29, Minister of Internal Affairs Ulan Niyazbekov held an online meeting dedicated to...

Kyrgyzstan and Russia – a union tested by time

In recent years, the "Central Asia +1" format has become an important tool for external...

The Family of the Hero of Kyrgyzstan Turdakun Usubaliev Against the Renaming of the Village of Kochkor

Relatives of the famous statesman Turdakun Usubaliev expressed their opinion on the proposal to...

Governance in Kyrgyzstan in the 18th to early 20th Century

The new period of Kyrgyzstan's history spans from the 18th to the early 20th century. It can...

Mahmud Kashgari "Diwan Lugat At-Turk"

The work of Mahmud Kashgari 'Divan Lugat At-Turk' ('Dictionary of Turkic...

The History of the Study of the Origins of the Kyrgyz People

Discussion Problems on the Origin of the Kyrgyz People In recent years, professional historians...

The trade turnover between Kazakhstan and Russia approaches 30 billion dollars, - Tokayev

President of Russia Vladimir Putin and President of Kazakhstan Kassym-Jomart Tokayev Tokayev noted...

Kyrgyz Weaving Loom

The southern Kyrgyz are also known for a manual device for cleaning raw cotton from seeds — the...

Kokshaal-Too and Peak Dankov

Remoteness, wildness, and mystery are the concepts that characterize and give an idea of this...