From the west of Mongolia, the Altai region has long remained in the shadow of larger archaeological explorations in Eurasia. However, in their new book, William Fitzhugh and Richard Kortum emphatically highlight the key role of this region in the development of nomadic cultures, hunting traditions, and ritual spaces. This is reported by MiddleAsianNews.

The authors, based on years of field research around Lake Khoton and the adjacent valleys, collect and analyze hundreds of rock images and burial objects. They use glacial bedrock as a metaphor and a real basis for 20,000 years of cultural continuity.

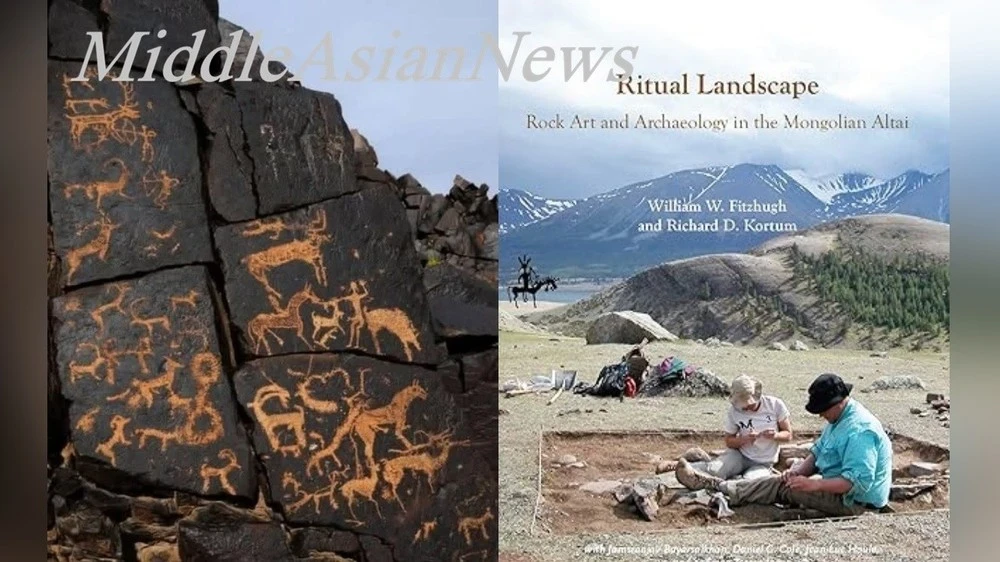

'Ritual Landscape: Rock Art and Archaeology of the Mongolian Altai' is a multilayered and meticulously crafted study that successfully combines the study of rock art with traditional archaeological approaches, creating an impressive picture of the unique geological landscape of the Mongolian Altai.

One of the significant outcomes of the work is the attempt to connect two often isolated fields of science – rock painting and archaeology. The authors demonstrate that rock art, viewed in the context of burial architecture and the surrounding environment, becomes an important part of human history rather than just an aesthetic object. This approach allows for a rethinking of petroglyphs as active elements of ritual and social life, linked to burials and ceremonial monuments.

The book stands out for its chronological coverage, allowing the development to be traced from the Upper Paleolithic to the historical pastoralist era. The authors describe changes in subsistence strategies, movements, and beliefs, some of which are still relevant today.

The work shows how the theme of rock art evolves from images of large wild animals to symbols of herds and, ultimately, to the iconography of nomads on horseback. This sequence, based on stratigraphic data and stylistic analysis, is crucial for understanding changes in life on the steppes.

Another unique feature of the book is its attention to landscape archaeology. The authors do not merely catalog objects but invite readers to perceive the Altai as a ritualized geography. Hills, rivers, and mountain passes become not just parts of the landscape but active participants in human history, emphasizing the importance of visibility and the characteristics of the terrain for the placement of images and monuments.

The book impresses with its high-quality illustrations, maps, and diagrams that beautifully complement the text. The visual elements play an important role in the research, which is deeply connected to graphic sources and the landscape. Researchers engaged in Central Asian cultural phenomena and nomadic societies will find this publication not only informative but also visually appealing.

It is worth noting that 'Ritual Landscape' not only answers many questions but also raises new ones. The work offers modern methods for dating rock paintings, calls for the integration of iconographic and archaeological data, and stimulates a rethinking of the roles of steppe societies as active cultural participants rather than just migrants.

Thus, the implications of this research may have a significant impact on future work both in the Altai and in similar regions.