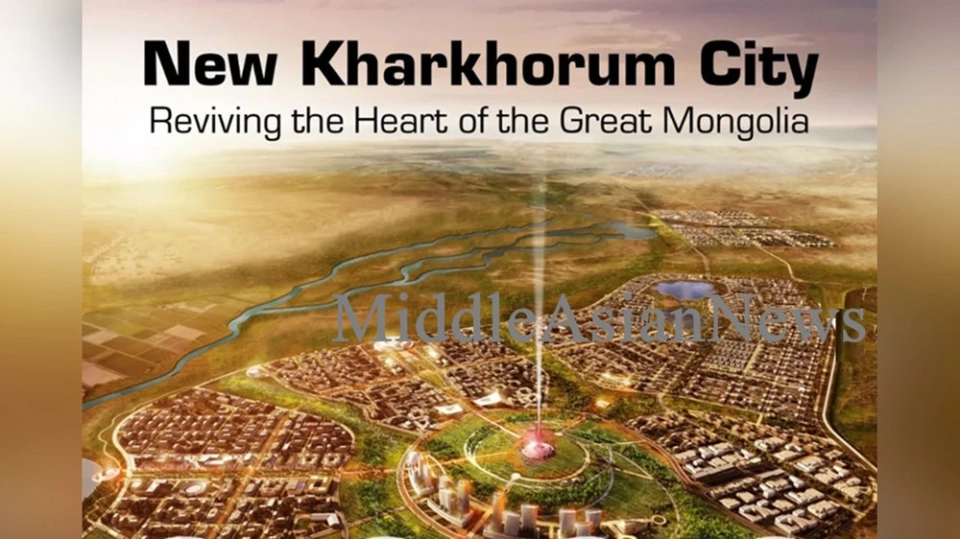

Mongolia intends to create a new city in the picturesque valley of the Orkhon River.

“Some Asian countries believe that a new capital can solve many old problems. But history shows that moving capitals rarely goes as smoothly as planners expect,” notes CNA.

In the early 13th century, uniting various nomadic tribes, Genghis Khan sought to find a sacred place for his vast empire.

According to legends, he received a shamanic vision of a blessed valley, under the protection of the Eternal Blue Sky, the divine patron of the Mongols.

This valley turned out to be the Orkhon River — a spacious plain where the wind blows eternally, beneath the boundless sky of Mongolia. For centuries, this place has been sacred and has served as a home to great cultures.

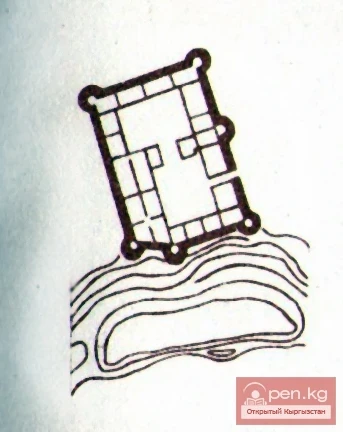

Once a strategic point on the Silk Road, it later became known as Kharkhorum — a cosmopolitan center of trade and crafts.

Decades later, Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, destroyed Kharkhorum, relocating the center of power closer to China, to Ulaanbaatar.

After that, Kharkhorum was forgotten, its palaces buried under the sands of time. However, the memory of it lives on, and steps are now being taken to create a new capital for the Mongolian people.

The country's government has developed an ambitious $30 billion project to return the center of power to its historical core. The new Kharkhorum is also expected to help solve pollution and traffic problems in Ulaanbaatar.

“Originally, Kharkhorum was a global cultural, political, and economic center, akin to modern New York,” says Khalkhar Luvsan, the mayor of Kharkhorum. He shares his thoughts on the new project from a modern office in Ulaanbaatar, where architects and engineers are at work.

“Our task is to connect this historical identity with modern principles of smart and digital urban planning,” he added.

The new Kharkhorum, located about 350 km west of the current capital, is just the latest chapter in the long history of this region.

Across the continent, governments are exploring the possibilities of relocating their capitals. Experts argue that these steps are aimed at correcting old mistakes and creating a new future.

Similar decisions have been made in countries like Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar.

Now the idea of relocating capitals is gaining popularity in various corners of Asia — from the jungles of Borneo to the floodplains of the Chao Phraya River: when problems arise in a country, the possibility of building a new center is discussed.

Indonesia is on the path to transferring governance functions to the new megacity of Nusantara, while Jakarta faces serious urban challenges.

In early 2023, Thailand's Ministry of the Interior studied the feasibility of moving the capital due to rising sea levels and frequent flooding affecting Bangkok.

South Korea is developing its administration as part of the "Sejong City" project, while in the Philippines, the creation of New Clark City has long been considered part of a decentralization strategy.

Like Indonesia, Mongolia, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, and South Sudan are striving to create a new sustainable center that is livable and environmentally friendly. This is a project for future generations.

“The appeal lies in the fact that it is a blank slate. It is a very inspiring idea,” comments Natalie Koch, a political geographer from Syracuse University in New York.

But behind the bright slogans and promises lies a complex reality, including elite ambitions, speculative investments, and compromises between symbolism and reality.

History shows that capitals are rarely moved as smoothly as planned. Examples from Abuja in Nigeria, Dodoma in Tanzania, Astana in Kazakhstan, and Naypyidaw in Myanmar demonstrate that many new capitals remain mere shadows of their ambitions.

“Building new structures on a blank slate is an appealing notion, but it does not address the underlying structural issues,” Koch stated.

The same questions that arose for leaders in other countries are currently facing Mongolia.

MANDATE OF MONGOLIA TO RELOCATE

Despite having one of the lowest population densities in the world, Ulaanbaatar feels cramped. Every morning and evening, the city faces severe traffic jams.

As winter approaches, the coal fleet activates, covering the Tuul River valley with toxic smoke that lingers for months.

“This city suffocates and oppresses. It is very inhospitable,” says Battushig Togtokh, head of the social enterprise Gerhub, which focuses on sustainable development in Ulaanbaatar.

Ulaanbaatar is pressed against its own borders, surrounded by mountains. On the outskirts, sprawling ger districts — traditional Mongolian tents — threaten the government's ability to provide essential services such as water supply and waste disposal.

The city, designed for 250,000 people, is now under pressure from 1.6 million residents, which is nearly half the population of the country on land that constitutes less than one-thousandth of a percent of all of Mongolia.

This situation can be termed “extreme population density,” notes Oyunbat Bataa, the director of urban planning for the Kharkhorum municipality.

“Everyone understands that Ulaanbaatar faces problems of traffic, pollution, and overcrowding. People are social beings, and when all opportunities are concentrated in one place, it is only natural that they strive to go there,” he said.

The “New Kharkhorum” project is seen as a solution to the shortcomings of Ulaanbaatar.

According to the government plan, by 2050, Mongolia's population could reach 5 million, with about 10% living in the Kharkhorum area, suggesting a city with a population of around 500,000.

Khalkhar Luvsan reported that after the general plan for the city is completed, its implementation will begin, which will take 12 to 18 months, with the goal of accommodating up to 30,000 residents within a decade.

The primary task will be to ensure transportation accessibility to the region; new road and rail routes, as well as an international airport, are planned.

The new capital project also includes the creation of an agricultural cluster, the restoration of ancient lakes, and the excavation of the original Kharkhorum, which will be transformed into an open-air museum for tourists.

Khalkhar noted that this is part of a strategy to create a transnational tourist route connecting Russia, China, Asia, and Europe through Mongolia.

Work has begun on the Great Khans Park — a memorial garden dedicated to the great rulers of Mongolia, where 700,000 trees have already been planted.

Urban planners expect that with the growth of the New Kharkhorum, businesses, social services, healthcare infrastructure, and educational institutions will develop, utilizing modern technologies and adhering to sustainable development principles.

“Of course, at the initial stage, it is difficult to imagine how to build a city from scratch. But we have dreams and goals, and we are determined to achieve them,” concluded Khalkhar.

LESSONS FROM INDONESIA AND ITS FUTURE CAPITAL

While the dream of a New Kharkhorum may be unique to Mongolia, its challenges are familiar to other countries in the region.

Decades before Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo announced the relocation of the capital to Nusantara, the country's founder Sukarno also had similar ideas.

He was dissatisfied with Jakarta, an overcrowded legacy of the colonial era. Instead, he planned the city of Palangkaraya in Central Kalimantan as a new center for the nation.

The city was built, but the ambitious plan was never realized.

When Jokowi announced the relocation of the capital to East Kalimantan in 2019, the site was chosen deliberately, yet the vision was entirely different, as noted by researcher Anders Kirstein Møller.

“Sukarno was a classic post-colonial idealist striving for the development of the country, while Jokowi is focused on high technology and modernization,” Møller added.

He argues that the foundations of Nusantara have created a “fragile” project, lacking consensus on its symbolism and priorities.

Nusantara was expected to become a green and smart city, achieving zero emissions by 2045.

Møller noted that the many trendy concepts surrounding the project could lead to disappointment when residents do not see the expected progress.

According to government plans, the initial cost of building Nusantara was around $32 billion, and large private investments will be needed to cover 80% of the expenses. It is expected that by 2045, up to 1.9 million people will live there.

Construction of Nusantara is actively ongoing, although it is in the early stages. Some key elements already exist or are under construction, while others remain only in plans.

However, the project faces rising costs and logistical challenges.

In September, it became known that the status of Nusantara was downgraded from “national capital” to “political capital” under President Prabowo Subianto.

TO RELOCATE OR NOT TO RELOCATE?

While Indonesia determines the future of Nusantara, neighboring countries are closely monitoring the situation.

Bangkok and Manila, two coastal megacities, also face viability questions for future generations.

The capital of Thailand is dangerously close to sea level — just 1.5 meters above.

Now the rising sea is almost at the doorstep of Bangkok, surrounded by roads, factories, and skyscrapers — a city whose own weight causes the ground to sink by 2 cm each year.

“I fear that there is nothing that could save the city,” says 64-year-old fisherman Sinsamut Phuttamiphon.

In light of these threats, quiet discussions about the possibility of relocating the government from Bangkok have been ongoing for several decades.

In the early 2000s, Thaksin Shinawatra's government commissioned a study on the feasibility of moving the capital to Nakhon Nayok, about 100 km northeast of Bangkok.

After the flooding in Bangkok in 2011, the question of relocating the government to a safer region arose again. In 2019, Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha proposed this idea once more as a way to combat traffic congestion.

This year, after a proposal from one of the legislators to move the capital to Nakhon Ratchasima province, the House of Representatives committee concluded that such a move would be too costly and would require a referendum. Instead, it recommended strengthening Bangkok's defenses, including the creation of marine barriers.

Nevertheless, the committee did not abandon the idea of relocation; it called for comparative studies of other countries that have moved their capitals.

Despite existential risks, landscape architect Kochakorn Woraakhom argues that before making a decision to relocate, resilience must be demonstrated.

“We need to adapt, not run away,” she says about a megacity that can thrive near water. “Let’s make it so that water unites us, rather than instills fear.”

“The history of Bangkok shows that we can live with floods. Even if the capital is moved, Bangkok's problems will still remain,” she added.

Manila also faces challenges such as ground subsidence, flooding, and earthquakes.

Governments are constantly considering relocation in search of improvement.

Filipino historian Michael Pante has observed how New Clark City is gradually developing 100 km north of Manila.

In 2018, this site was proposed as a disaster-resilient backup center. However, completion of construction is scheduled for 2065, and the potential population will be 1.2 million, making the project more extensive than just a contingency plan.

It is envisioned as a “smart city,” protected from natural disasters and featuring a functioning international airport situated 60 meters above sea level.

Nevertheless, Pante describes the new city more as a refuge than a replacement for the capital.

According to him, the Philippines' priorities are now more practical than symbolic: they are focused on protecting governance and attracting investments.

The Philippines has long sought to shed its colonial legacy. The capital was moved to Quezon City shortly after gaining independence in 1946 to form a new identity.

According to Pante, the capital existed for nearly three decades before being returned to Manila, and since then, the desire to rid itself of the past has weakened.

“There are no serious attempts to position Clark as a city that will replace Manila, but rather as a supporting city, considering that Manila cannot provide essential services to all its residents,” he added.

“If Clark can create enough jobs, that would be good. But not at the expense of displacing people from their ancestral lands or using this as an excuse to ignore Manila's problems,” he emphasized.

QUESTIONS OF LEGITIMACY AND LEGACY

Debates about a new capital are often presented as a benefit to society, a way to combat climate change, and a stimulus for national progress.

However, according to Koch, it is essential to consider who controls the narrative, who benefits from contracts, and who leaves their legacy.

These issues she has studied in other countries. Often where projects do not materialize, financial flows are directed to the elite.

“It is important to ask the question: ‘Who is this capital successful for?’” she adds.

“It is hard not to notice that many projects in both democratic and undemocratic countries represent attempts by the elite to profit. The reason many places remain empty is that those who mattered have already received their money,” she continues.

In Indonesia, as noted by Markus Meitzner from the Australian National University, the Nusantara project has become more of a personal legacy than a common national agenda.

“Jokowi sees Nusantara as his main legacy, symbolizing his political boldness. However, critics view this as his recklessness and disregard for careful planning,” he added.

According to Meitzner, the ex-president's decision created an “inefficient hybrid” that was actively promoted by one leader and inherited by the next. Successful execution requires elite consensus, which, he says, has been absent from the start.

While Prabowo has reaffirmed his commitment to Nusantara, his government has developed numerous priority programs for 2026, including food security, education, and defense, but not specifically the new capital.

Due to the ambiguity of Prabowo and other issues related to location and planning, Benny Subianto, a consultant at Harvard Kennedy School, noted that Nusantara could become either a “bureaucrats' city” or a “ghost town.”

“I doubt that Nusantara will become a symbol of renewal. The project is likely to hit a dead end,” he concluded.

In Mongolia, Togtokh is concerned about the feasibility of the New Kharkhorum, which requires significant funding.

Trust in the government has recently fluctuated. In June, then-Prime Minister Oyun-Erdene Luvsannamsrai resigned after a vote of no confidence triggered by youth protests against corruption.

Mongolia faces serious structural issues related to corruption. According to Transparency International's corruption perception index, the country ranks 114th in the world, and 69% of surveyed Mongolians consider government corruption to be a “serious problem.”

In March, the UN Human Rights Committee expressed concern about “widespread corruption in Mongolia, especially at high levels,” and noted the lack of systematic enforcement of anti-corruption legislation.

“The situation requires not creativity, but moral responsibility,” noted Togtokh.

“When moral standards are absent, no planning or design will lead to success,” he added, commenting on the plans for the new capital.

Khalkhar is aware of the complexity of the upcoming tasks but hopes for the support of the government and the people in realizing the New Kharkhorum.

“The success of the project depends on quality planning. If it is well thought out, the project will be successful,” he concluded.

THE TRAP OF TWO CAPITALS

Worldwide, many countries face the problem of “two capitals.” Governments manage ministries but do not understand the needs of the population.

In Kazakhstan, the process of legitimizing the new capital Astana took much time and effort. Naypyidaw in Myanmar, located in a strategically important place, also struggled for a long time to become a fully-fledged city.

In 1999, the Malaysian government moved its residence to Putrajaya to relieve Kuala Lumpur. However, Putrajaya remains overshadowed by the city it was meant to relieve.

Other capitals, such as Canberra, Islamabad, and Brasília, have become prosperous cities, but this took decades and significant investments.

According to Møller, such investments can be costly for existing cities and must be considered in planning.

In modern capitals, issues such as pollution and congestion still require funding and attention from governments.

“If you spend time and effort on complicated projects, you have no resources left to address other, less attractive issues,” he says.

Chintan Raveshia from Arup notes that if principles of governance and sustainability are not adhered to in the early stages of constructing a new capital, “this could create serious legitimacy problems for the city for the next 20 years.”

“The biggest problem with the new capital is the lack of historical memory. It is memory that creates cities,” says Raveshia, head of urban planning in the Asia-Pacific region for Arup, which has worked on Nusantara.

“When there is no memory of generations, there is no sense of community either.”

Raveshia emphasizes that real sustainability requires designing with nature in mind, an approach that is carried out gradually, through care and connection, rather than through rushed construction.

However, even with promises of eco-friendliness, the process of new construction proves to be complex. In Nusantara, thousands of hectares of tropical forest have been cleared to accommodate a city with a zero carbon footprint.

“Environmental considerations cannot be an excuse for destructive construction,” concludes Koch.

Residents of the Orkhon River valley experience mixed feelings: hope and uncertainty about the future. This historically significant region has long suffered from underdevelopment.

“I believe they can create a beautiful city in a short time. That’s what I want,” says Ganbat Sandag, a shop owner.

“This is a unique and historically rich place,” adds Saraa Banzar, owner of a souvenir shop near the Erdene Zuu Monastery, built on the site of the old Mongolian capital.

“I hope the Mongols can make it happen. But honestly, I’m not sure,” she says.

Standing on the open plains of the old Kharkhorum, where grass covers the stones of the ancient empire, one cannot help but wonder what mark the new city will leave here.

author: Jack Bord

translation: Tatar S.Maidar

source: MiddleAsianNews