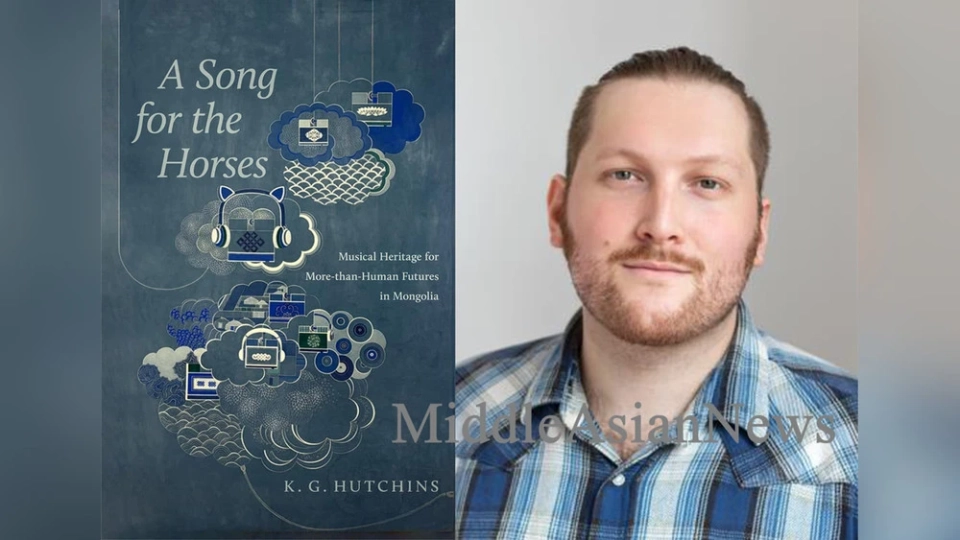

Kip Grosvenor Hutchins, a cultural anthropologist and visiting assistant professor of anthropology at Oberlin College, focuses on exploring the connection between music and the environment. His work spans post-socialist Mongolia and the Southern Appalachians, where he employs multimodal ethnographic research methods. Since 2010, Hutchins has collaborated with musicians, educators, herders, and cultural administrators in the Dundgovi aimag and the capital of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar.

In October 2025, the world saw his debut book titled "The Horse Song: Musical Heritage for a Non-Human Future in Mongolia," published by the University of Arizona. In this work, Hutchins demonstrates how Mongolian musicians use their cultural heritage to shape an ecologically sustainable future that transcends capitalist devastation and climate change.

This week, the University of Arizona Press released Kip Hutchins' book "The Horse Song: Musical Heritage for a Non-Human Future in Mongolia."

“When I started my undergraduate studies, I enrolled in a Mongolian language course because it was the only language I knew nothing about. Participating in the classes immersed me in the local community's life, which ultimately led me to Mongolia to teach English and study music. Upon arriving there, I saw that the nomadic way of life is still alive, which is remarkable in the modern world where many nomadic peoples face oppression or are forced into urbanization. This realization opened my eyes to the possibility of alternative ways of living and futures,” Hutchins shared.

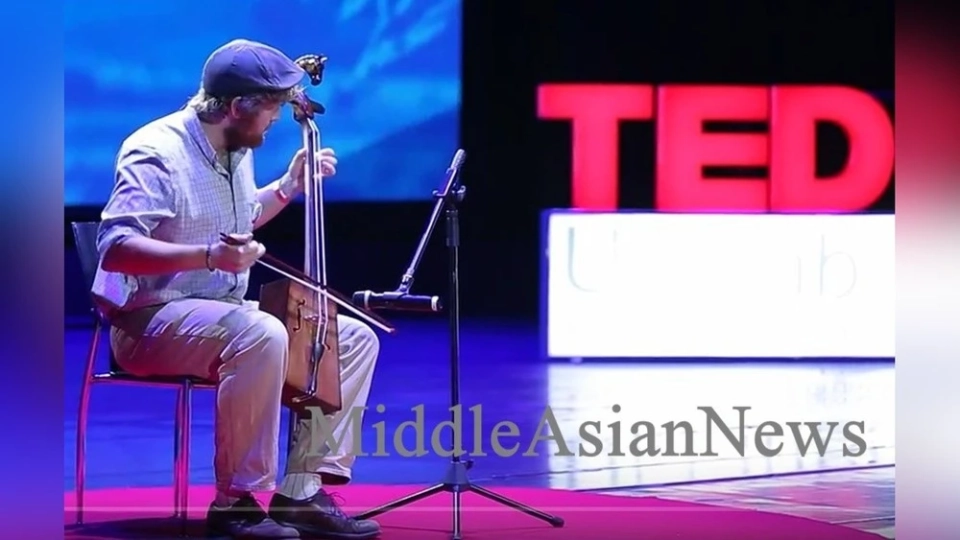

“The morin khuur became my primary instrument in my research. Playing with other musicians or learning songs from experienced performers created unique opportunities for communication that might not have otherwise happened. In the book, I share vivid memories of my performances on the morin khuur. One of my favorite events was playing the morin khuur with three respected herders at the 'nair' festival in the Gobi. This memory is tied to a cold winter rehearsal with the orchestra in Ulaanbaatar, where we were all in winter coats due to the lack of heating in the concert hall. My most unusual performance took place at a TedXUlaanbaatar event, where one of the students asked me to play the morin khuur and give a short speech in Mongolian. I think the video from that performance can still be found online,” he added.

In response to the question: “One chapter of your book mentions that three singers during a performance represented different parts of the Gobi landscape. How do geography and spiritual connection to the land influence the performance of Mongolian music?”

“There is a Mongolian musical genre known as urtyn duu, which translates to 'long song' in English. Performers unfold rich, relatively short texts against a backdrop of semi-improvisational melodies. The main idea of this genre is that the landscape possesses moral qualities. The steppe, vast and serene, symbolizes generosity, while the high Altai mountains, with their neighboring peaks, are a source of joy. Musicians allow the terrain to guide their improvisations, creating melodies that either flow smoothly or change rapidly, reflecting the silhouettes of the mountains. Ideally, a magnificent performance helps the singer to understand the moral character of the landscape more deeply and evoke similar feelings in the listeners,” Hutchins explained.

In a broader sense, a future beyond the human is envisioned as a possibility based not on human dominance over nature but on understanding the interdependence of people with non-human beings, plants, and the earth. Mongolia is situated between the thawing permafrost in Siberia and the desertification of the Gobi. People, from nomads to urban dwellers, face two climate crises that they do not control and in which they have little involvement. In response, musicians and herders use music to establish connections with non-human beings and spiritual landscapes, helping to create a climate-resilient future, as it places people on the same level as ecological others, rather than above them.

The book is available for purchase on amazon.

Considering the thawing of permafrost in Siberia and the transformation of the steppe into the Gobi desert, the residents of Mongolia are facing climate crises. Some nomads view climate change as the end of the world; however, they also note that for indigenous peoples of Northern Asia, this has already happened when colonization altered their lives. In K.G. Hutchins' book "The Horse Song," the responses of people to climate change, based on their cultural heritage and aimed at strengthening social resilience, are explored.

Hutchins' work, spanning over a decade, provides a vivid and insightful portrayal of the lives of Mongolians. Musicians use the morin khuur, or 'horse fiddle,' to interact with animals and the environment. This work makes an important contribution to posthumanist studies in the social sciences, drawing on the works of scholars such as Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing.

Given the global climate change, the book offers a unique perspective on the use of cultural heritage as a tool for addressing ecological issues, providing important lessons for global efforts to create a sustainable future. By connecting music, ecology, and posthumanism, "The Horse Song" demonstrates how Mongolian musicians utilize their traditions to shape an alternative future free from climate change and neoliberalism.

Tatar S. Maidar

source: MiddleAsianNews