Kyrgyz Cinema

The first founding congress of the Union of Cinematographers of Kyrgyzstan opened on October 24, 1962. At that time, it had 33 members. Today, two decades later, the group of Kyrgyz cinematographers has tripled in size.

The very emergence of Kyrgyz cinema is inextricably linked to significant milestones in the socialist construction in the USSR.

During the years of the second five-year plan, together with the entire Soviet people, the Kyrgyz people completed the transition to socialism. In the mountainous region, as in the entire country, fundamental socio-economic changes occurred. Poverty and oppression became a thing of the past. Kyrgyzstan transformed into a socialist republic with a highly developed economy and culture. The Kyrgyz socialist nation was finally formed. Unlimited prospects for further economic and cultural growth opened up before it.

One of the primary tasks of cultural construction during the third five-year plan became the creation of a national cinematography. To address this, the government of the republic adopted a series of resolutions between 1937 and 1939 that defined specific measures for organizing production and releasing newsreels: “On the allocation of 30,000 rubles for the release of the sound newsreel of Kyrgyzstan for the 20th anniversary of the October Revolution” (October 14, 1937), “On the organization of a permanent correspondent point of the Tashkent studio ‘Soyuz-kinokhronika’ in the Kyrgyz SSR” (October 14, 1937), “On the allocation of 25,000 rubles for covering the expenses of the newsreel ‘Meeting of Comrade Fedorov’” (July 21, 1938), “On the organization of a permanent correspondent point of the Tashkent branch of Glavkinokhronika in the city of Frunze” (June 4, 1939), “On the allocation of 10,000 rubles to the Filmification Department of the Council of Ministers of the Kyrgyz SSR for sending students to study at the State Institute of Cinematography in Moscow” (July 14, 1939). These facts are significant, confirming the purposeful efforts made. As a result, operators from the Tashkent film studio, including M. Kayumov, M. Kovnat, N. Golubev, D. Soda, and A. Rakhimov, periodically visited the republic. Starting in January 1940, they, along with directors E. Vasilenko, V. Usova, and B. Veiland, began to release the newsreel “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” monthly, which quickly gained popularity.

Continuing to implement the planned initiatives, the government of the republic decided on August 10, 1940, to organize an independent division of the newsreel studio in the Kyrgyz SSR and to allocate 7 rooms in the building of the music school for its placement. Following this, another decision was made to allocate funds for equipping a film crew to the Inylchek glacier—one of the subjects of the future documentary film “Poem of the High Land”.

On November 15, 1940, I. Kolsanov, a qualified and experienced operator who had worked at “Lenfilm” and the Leningrad newsreel studio until 1937, began his duties at the Frunze correspondent point, sent from Tashkent. In the autumn of 1941, M. Vareikis, a director from the Central newsreel studio, joined him. Evacuated from Moscow to Tashkent, she first traveled to Frunze and filmed the documentary “Poem of the High Land” (released as “On the High Land”), then edited issues of “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” at the Frunze correspondent point.

The initial stage of building the national cinematography, the necessity of which was discussed in May 1939 by the Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kyrgyzstan A. Vagov and the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of Kyrgyzstan T. Kulatov in the pages of the newspaper “Kino,” concluded on November 17, 1941, with the resolution of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Kyrgyz SSR on the organization of a newsreel studio in the city of Frunze. On December 15, the Committee for Cinematography under the Council of Ministers of the USSR appointed A. Avdenis as the director of the new film enterprise. Director M. Vareikis and operator I. Kolsanov were transferred from Tashkent to the newly organized Frunze film studio starting January 1, 1942.

Why was it necessary to present the facts and documents surrounding the emergence of Kyrgyz cinema in such detail and strict chronological order? Because they are irrefutable evidence of the significant practical activity of party and Soviet bodies in the construction and material support of the nascent Kyrgyz cinematography.

It is also important to emphasize that the newsreels of 1940-1945 laid a solid foundation for the development of Kyrgyz documentary cinema in the post-war years. Their characteristics were determined by the demands of the time, the conditions of film production, and the creative level of directors and operators. The newsreel “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” began to be released in anticipation of the 15th anniversary of the republic.

Focusing on this significant event, directors and operators tried to show as broadly as possible the life and work of all regions and cities of Kyrgyzstan. In the small-volume newsreel (150-180 m) and within the framework of 4-6 short stories (25-40 m), the working days of shepherds in the Tian Shan and Susamyr, field workers in the Osh and Issyk-Kul regions, miners in Kyzyl-Kiya, builders of the BChK, and the railway from Rybachye to Frunze, as well as the cultural life of the republic, were captured. In 1940, in a special issue of “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” (No. 7-8) titled “The Road to Susamyr,” the informational display of the construction of the highway was accompanied by a voiceover in Kyrgyz.

The voiceover comments were translated and edited by journalist D. Bekboev, who headed the newspaper “Leninchil Zhas.” Subsequently, many writers and newspaper essayists from Kyrgyzstan would follow his example.

An undeniable merit of the first Kyrgyz film periodicals was the extensive geography of each issue and the prompt coverage of current events.

With the onset of the Great Patriotic War, the content of “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” directly echoed the publications of republican newspapers. The fourteenth, July issue of the newsreel consisted of stories that began with calls like “All the people’s forces—against the enemy,” “All—for the Motherland,” “Be at the factory as in the ranks, fight for your Motherland.” Starting in September, each issue of “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” opened with a front-line film report. The rhythm of the military chronicle, conveying the tension of the heroic struggle against the fascists, became like a metronome for filming events in the republic, far from the front.

Almost all of 1942, a small team of the studio, along with editor and poet Kubanych Akayev, announcer and director of the theater Azhygabul Aydarkulov, despite numerous production difficulties, released the newsreel “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” on time.

A notable place in the film periodicals of 1943 was occupied by thematic newsreels “Women of Kyrgyzstan During the Great Patriotic War,” “Evening of Kyrgyz Art” directed by M. Vareikis, and the special issue “Kyrgyzstan During the Patriotic War” by D. Erdman. During this time, operators increasingly attempted to move away from static filming. The dynamics of the chronicle frame were enhanced by camera movement, both vertically and horizontally. Work began on creating cinematic forms.

Starting in October 1944, the newsreel began to be released in two languages: Kyrgyz and Russian. The composition of its authors changed. Instead of those who returned to Moscow, M. Vareikis, V. Sharapova, and I. Gunger, sound operator V. Kopotev and assistant operator N. Nikolaeva arrived from the Penza correspondent point of the Kuibyshev newsreel studio.

Front-line film operator G. Shulyatin was replaced as director by G. Nikolaev, an operator with twenty years of experience in cinema, who led the Voronezh newsreel studio during the war and then headed the Penza correspondent point. He paid great attention to expanding thematic planning at the studio. The practice of monthly reviews of the operators’ work on stories continued, during which control over creative growth was maintained, and initiative and the search for new ideas were encouraged.

In 1946, the entire team of the Frunze newsreel studio participated in the creation of the feature film “Song of Kyrgyzstan,” which received the title “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” in 1947 during its release. The group of operators from Moscow, Tashkent, and Almaty (A. Frolov, A. Rakhmanov, M. Aranychev) included a new employee of the studio, S. Avloshenko, and F. Mamuraliyeva joined the international brigade as an assistant director.

Director M. Slutsky and poet A. Tokombaev conceived a song about the republic. Naturally, the performance of folk singers at the beginning of the film appears as a report episode. The akyns praise their native land, the labor of its best sons and daughters. And as if through the eyes of wise folk artists, the audience sees Kyrgyzstan in the 1940s, transformed by socialist construction, having endured severe wartime trials, and continuing its unstoppable movement forward, along the path to happiness indicated by V. I. Lenin.

M. Slutsky managed to unite informational frames about the inspired labor in factories, plants, mines, and on collective and state farm fields with the theme of courage and unity of the people during wartime and peacetime. The image of the masterful people of Soviet Kyrgyzstan is formed from expressive portraits of livestock breeders, miners, collective farmers, scientists, and cultural figures.

In 1947, on the 30th anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution, the studio released three short films: “Socialist Livestock Breeding of Kyrgyzstan,” “Valley of Sugar,” and “Artistic Self-Activity of Kyrgyzstan” (director D. Erdman, authors-operators S. Avloshenko and G. Nikolaev). Unfortunately, only “Valley of Sugar” has survived. All issues of the newsreel “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” from 1946 to 1949 have also been lost. Surviving montage sheets and archival documents testify to the release in 1947 of special issues: “Film Portrait,” “O. T. Semichkin” (about the director of the children’s home named after N. K. Krupskaya), dedicated to the elections to the Supreme Soviet of the Kyrgyz SSR. Director D. Erdman edited the chronicle film “Holiday of the Kyrgyz People.”

To systematically cover the life of the southern republic, a correspondent point was opened in Osh.

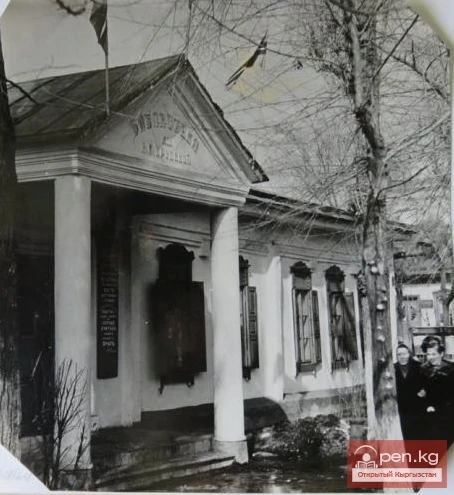

The dubbing workshop transferred to the Frunze newsreel studio from 1949, headed by G. Osmonalieva (who was transferred from the “Soyuzmultfilm” studio), translated films such as “The Tale of a Real Man,” “Meeting on the Elbe,” “Court of Honor,” “Happy Sailing,” and “Michurin” into Kyrgyz.

During 1948, “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” published 48 film stories promoting the lifestyle and working methods of Heroes of Socialist Labor. In 1949, the genre of film portrait already occupied a permanent place in the structure of the newsreel. These facts prove that the studio was in line with the overall movement of Soviet cinema, participating in solving its main task—to educate the masses through the examples of labor leaders.

In 1950, the reconstruction of the new premises of the Frunze film studio was completed. The expansion and equipping of its production base were facilitated by many film organizations in the country, as well as several ministries of the republic. Much was accomplished during this time by Nikolaev's successor V. Belyaev—a qualified operator who had worked at the studio since 1945.

The 1950s marked a special stage in the activities of the Frunze studio of chronicle-documentary films. The volume of film production significantly expanded. The newsreel became bi-weekly, of normal footage (250-300 m).

Systematic dubbing of films into Kyrgyz was established. The best actors from the Kyrgyz Drama Theater were involved in this important work.

However, the demands for the chronicle—the studio's main product—sharply decreased at the beginning of this period. The life of the regions and remote areas of the republic was hardly covered. The range of themes and professions narrowed. There was a decline in the skills of operators and directors.

The labor of workers and rural laborers was shown in a standard, dull manner. The press justly reproached film journalists for their inability to highlight remarkable facts and create journalistic generalizations based on them.

The situation with the chronicle began to change in 1953. Stories increasingly featured frames revealing the roots of certain events and actions of people. In lyrical episodes, warmed by the feeling of authorial participation, there was a noticeable desire to penetrate the sphere of human experiences. It is no coincidence that almost every issue included synchronously filmed portraits. An active attitude toward reality manifested itself in critical stories about problems in industry, construction, and transportation.

The issues of “Soviet Kyrgyzstan” from 1957 to 1959 vividly confirm the strengthening trend toward seeking new approaches, expanding themes, and diversifying their presentation through film reporting. It was in this vein that the documentary films “Dam in the Mountains,” “BChK” by D. Erdman, “Bon Voyage” by F. Mamuraliyeva, “They Were Born in Tian Shan,” “Me and My Friends,” “Your Friends” by L. Turusbekova, and “In the Valleys of Kyrgyzstan” by M. Kulte were born. They, of course, differ in genre characteristics and journalistic content.

The desire to enter the daily lives of ordinary people, to support the progressive and to expose the stagnant and backward, naturally gave rise to a journalistic approach to phenomena of reality and, as a consequence, the release of the newsreel “Love Your City,” in which the civic position of filmmakers was expressed not only in the announcer's text but also in the very montage organization of facts.

In the second half of the 1950s, alongside film journalism, the development of feature cinema began. The first Kyrgyz color feature film “Saltanat” was released at the “Mosfilm” studio by Vasily Markelovich Pronin at the end of 1955. It told simply, without embellishment and smoothing over sharp angles, about the fate of a Kyrgyz woman. Screenwriter R. Budantseva and director-producer truthfully depicted the complexity and contradictions of Saltanat's character. In the heroine's soul, a proud, intelligent person constantly battles with a family slave who retreats before her husband's tyranny. Yet the desire for freedom and the wish to uphold her personal dignity overcome all obstacles. With surprising mastery for a debutante, the talented actress B. Kydykeeva played the role of Saltanat vividly and passionately.

After the film “Saltanat,” the Frunze studio began to independently produce feature films.

Directors invited from Moscow, I. Kobyzov, A. Ochkin, and V. Nemolyaev, turned to the experience of national literature, rightly believing that it would help Kyrgyz feature cinema to stand on its feet. However, the visiting filmmakers, poorly acquainted with the real life of the Kyrgyz people, completely relied on the scripts of local authors, who had only tried their hand at film dramaturgy. Therefore, their films “My Mistake” (1957), “Toktogul” (1959), “Girl of Tian Shan” (1961) left much to be desired artistically.

The film “Far Away in the Mountains” (1958), resolved by director A. Karpov in the traditions of historical-revolutionary cinema, turned out to be significantly more successful. The attempt to create a film with a philosophical subtext, “Legend of the Icy Heart” (1957), undertaken by debutants E. Shengeley and A. Sakharov, did not go unnoticed for the development of Kyrgyz cinema.

An interesting proposal for a new genre in national cinema was the ballet film “Cholpon—Morning Star” (1959) by R. Tikhomirov.

However, it was not with these films that Kyrgyz cinema found its identity. As an aesthetic phenomenon, it was established in the following two decades.

The innovation of Kyrgyz documentary and feature cinema developed and strengthened in the 1960s based on significant changes in the economic and cultural life of the republic.

The characterization of this period, like the previous ones, is unthinkable without considering the newsreel “Soviet Kyrgyzstan.” It continued to serve as a creative laboratory for the “Kyrgyzfilm” studio. Many themes and findings of widely known documentary films trace back to the magazine stories, which in 1961-1965 increasingly acquired the traits of figurative journalism.

From the mid-1960s, the search for new ways to organize chronicle material and the desire to use them to reveal the life of the republic and its people more deeply captivated all directors. The best of their documentary films “In the Snows of Alai” and “Following Spring” were released by I. Kokeev and L. Turusbekova—today representatives of the older generation of Kyrgyz filmmakers. During this period, the creative development line of one of the first workers of the film studio, I. Gershtein, can be defined as a movement from chronicle to film journalism and socio-psychological documentary. In each of his films from the 1960s, whether “Right Flank,” “Three Answers to the Mountains,” “Chingiz Aitmatov,” “Pamir—the Roof of the World,” or “Change,” “There, Beyond the Mountains, the Horizon,” “The Cape of Gnedoy’s Horse,” the director sought to reveal the social and public patterns in reality and their reflection in the psychology of the characters.

In the very first films “Turning to the Sun” (together with I. Morgachev), “PSP,” the rare talent of A. Vidugiris opened up, seeing something special in a person, deciphering their character through gesture, mimicry, movement, speech, and intonation. The human being in complex relationships with nature, the human being and the creation of material and spiritual values—these are the main subjects for the artist’s reflections.

The activities of M. Ubukeev, B. Shamsiyev, and T. Okeev were of great importance for the aesthetic formation of Kyrgyz documentary cinema. They embarked on an independent path when the pursuit of poetic expressiveness became the leading trend in Soviet cinema. Returning from Moscow to the “Kyrgyzfilm” studio in the early 1960s, Ubukeev, Shamsiyev, and Okeev learned to combine the personal, national, and international through the works of Ch. Aitmatov. Starting with documentary filmmaking, they could not help but consider that the aesthetic consciousness of their native people had been nurtured for centuries by the epic “Manas” and its great storytellers. In general, a whole complex of ideological and aesthetic prerequisites prompted Kyrgyz directors to choose a direction in their work that combined the poetic traditions of the epic with documentary filmmaking. The films they created, “Manaschi,” “Shepherd,” “Children of the Mountains—Sons of the Sea,” “These Are Horses,” and “Muras,” received high praise from Soviet and foreign press. The first successes of Kyrgyz feature cinema in the 1960s are inextricably linked to the work of Ch. Aitmatov. Gaining all-Union fame and recognition from readers and critics in the late 1950s, it attracted the attention of young Moscow directors A. Sakharov, L. Shepitko, and A. Mikhalkov-Kontchalovsky.

Based on the works “My Poplar in a Red Scarf,” “Camel’s Eye,” and “The First Teacher,” they made the films “Pass,” “Heat,” and “The First Teacher.” Each of these films significantly deviated from the literary source. However, while Sakharov in “Pass” did not take into account the romantic, lyrically excited intonational structure of “My Poplar,” Shepitko in “Heat” and Mikhalkov-Kontchalovsky in “The First Teacher” not only captured the tonal style of Aitmatov but also attempted to find an adequate cinematic imagery for it. As a result, two talented works were born.

Studying the successes of predecessors in Kyrgyz feature cinema and relying on the rich experience of Russian art, M. Ubukeev, T. Okeev, and B. Shamsiyev created socially sharp feature films “White Mountains” (“Difficult Crossing”), “The Sky of Our Childhood” (“Pasture of Bakai”), “Shot at the Karash Pass.” In them, they managed to bring the means of cinematic expressiveness closer to national poetry. Importantly, each film is far from ethnographic isolation and separation. In its content and form, everything is understandable to any audience.

Studying the successes of predecessors in Kyrgyz feature cinema and relying on the rich experience of Russian art, M. Ubukeev, T. Okeev, and B. Shamsiyev created socially sharp feature films “White Mountains” (“Difficult Crossing”), “The Sky of Our Childhood” (“Pasture of Bakai”), “Shot at the Karash Pass.” In them, they managed to bring the means of cinematic expressiveness closer to national poetry. Importantly, each film is far from ethnographic isolation and separation. In its content and form, everything is understandable to any audience.The 1970s in the life of the working people of the republic passed under the sign of implementing the decisions of the XXIV and XXV Congresses of the CPSU. This historical period was marked by significant socio-political events—the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the birth of V. I. Lenin, the 50th anniversary of the formation of the USSR, the 50th anniversary of the Kyrgyz SSR and the Communist Party of the republic, the 30th anniversary of Victory over fascist Germany, and the 60th anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution.

Naturally, the “Kyrgyzfilm” studio tried to keep pace with the entire country, creating documentary and feature films about the heroic past and bright present of the republic.

The artistic films “Bow to the Fire,” “Crimson Poppies of Issyk-Kul,” “Red Apple,” and the documentary films “The Brass Band Plays,” “Chingiz Aitmatov,” “Responsibility,” and “You Walk Through Life” did not go unnoticed on the screens of the country.

Modern Kyrgyz documentary cinema consists of works by artists with different individual styles, thematic and aesthetic preferences. Directors B. Abdildaev, V. Vilensky, K. Orozaliev, Zh. Rakhmatulin, L. Turusbekova, S. Davydov, Sh. Apylov, and A. Baitemirov have all made their contributions to the overall collection.

Feature cinema is equally diverse. Its progressive movement includes not only films that have received awards at all-Union and international film festivals—“White Steamboat,” “Ulan,” “Early Cranes.”

The panorama of the achievements of “Kyrgyzfilm” is significantly complemented by the films “Mother's Field,” “Street,” “The Eye of the Needle” by G. Bazarov—a bold artist who walks untrodden paths in his work. In the late 1960s, director U. Ibragimov drew attention with his documentary films “Motif,” “Lava.” In the 1970s, in feature films “By the Old Mill,” “Smile on the Stone,” “Road to Kara-Kiyik,” “Field of Aysulu,” he tirelessly honed his professional skills.

In recent years, the studio has been enriched with directors and operators who are graduates of VGIK. Their first serious works have been released: “Sunny Island” and “Three Days in July” by K. Akmataliev, “Burma” and “Process” by D. Sodanbek; “Among People” by A. Suyundukov (together with B. Shamsiyev). Not only the mentioned ones, all the young people are capable individuals, and they should become the successors of their older brothers in art in the development and improvement of Kyrgyz Soviet cinematography. However, one thing is concerning. According to long-established practice, newcomers are given the opportunity to take their first steps in the newsreel “Soviet Kyrgyzstan.” It is very important that the new replenishment inherits the tradition of deep respect for documentary cinema—the very foundation on which all Kyrgyz cinema has grown. The best works of Kyrgyz filmmakers have always been characterized by sharp journalistic quality. Meanwhile, both in the stories of young operators and in the essays of their fellow directors, there is a clear preference for “pure chronicle.” Factography pushes imagery aside. In the context of the reduction of film periodicals under the influence of television news programs, such a trend signifies a backward movement, a repetition of what has already been passed.

With the constant support and assistance of experienced masters, it will be easier for the young to overcome the pitfalls that await them. This unwavering concern is shown by the State Cinema and the Union of Cinematographers of the republic, fulfilling the resolution of the Central Committee of the CPSU “On Working with Creative Youth.”

In our cinema, the role of the film director, whether in feature or documentary films, is, as it should be, the main one. However, it would be unfair to forget about the playwright, thanks to whose talent and skill the ideological and artistic foundation of the future film is born each time. Indeed, not every year does a talented script appear, and it is even more difficult to attract bright literary personalities to cinema. Nevertheless, the ranks of Kyrgyz screenwriters are growing. Such devoted authors of the muse of cinema as K. Omurkulov, B. Zhakiev, M. Gaprov, E. Borbiyev, A. Jakypbekov, L. Dyadyuchenko, R. Chmonin, I. Ibragimov, and K. Zhusubaliev are held in deserved respect.

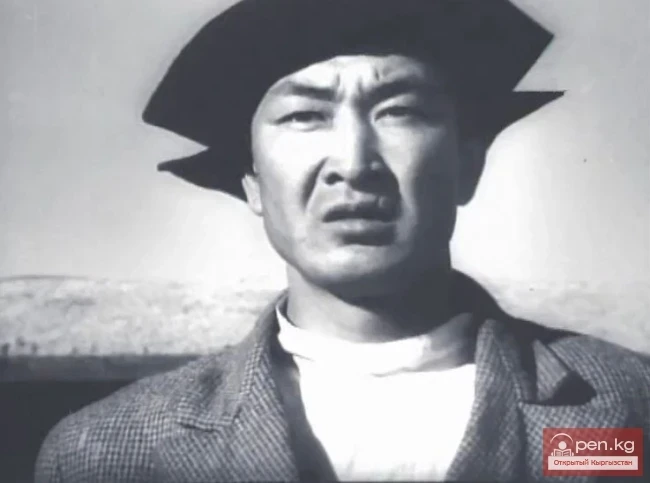

Actors have done a lot for the development of Kyrgyz cinema. Masters of stage and screen M. Ryskulov, B. Kydykeeva, D. Kuyukova, A. Zhangorozova, S. Kumushalieva, S. Jumadylov, D. Seydakmatova were equal partners with directors and screenwriters in the creation of all significant films. Alongside these names, A. Umuraliyev and K. Yusupzhanova gained fame beyond the republic. The first professional film actor B. Beyshenaliev acted not only at various studios in the country but also in Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

And, of course, the significant successes of modern Kyrgyz cinema are inseparable from the contribution of S. Chokmorov—a prominent and bright personality. He gained great popularity in the country and was repeatedly recognized as the best performer of male roles at all-Union film festivals.

The unforgettable image of Urkui Salieva was created on screen by the highly gifted T. Tursunbaeva.

Young G. Azhibekova, Ch. Dumanaev, and N. Mambetova began their lives in cinema with several successful roles.

The unique path of Kyrgyz cinema was also paved in the 1960s and 1970s by operators.

The mastery of K. Kydyraliyev, M. Musaev, N. Borbiyev, M. Turatbekov, M. Dzhergalbaev, A. Kim, supporting the thoughtful work of directors, significantly increased the ideological and aesthetic impact of films. These operators sought to move away from visual monotony, from repeating solutions to framing and composition found by others.

Artists S. Ishenov, A. Makarov, and K. Zhusupov also tried to be equally independent. Finally, the thirst for creative exploration in the past two decades has equally determined the character of the participation of talented composer T. Ermatov in the creation of films.

Dozens of people from different professions, with varying degrees of talent, but equally devoted to art, built Kyrgyz cinema. They were supported by outstanding masters of Soviet cinema S. Gerasimov, S. Yutkevich, Yu. Raizman, L. Trauberg, A. Zguridi, A. Galperin, and the teaching staff of VGIK and LIKI. All this was a manifestation of the great creative power of friendship and mutual assistance among the peoples of the USSR. The very rise of Kyrgyz cinema is the result of the comprehensive development of the cultures of socialist nations, their gradual rapprochement, and constant mutual enrichment, carried out by the Communist Party in accordance with Lenin's national policy.